(PONARS Policy Memo) Russian organized crime has high levels of sophistication and well-developed networks of corruption. It influences a considerable portion of the economy and spills across national borders. In this regard, Russia’s National Security Strategy, approved by the president in December 2015, included organized crime on its list of major threats to public safety. Despite the introduction of an electoral filter to remove previously convicted candidates, including those with relations to powerful criminal groups, they have still been able to enter Russia’s political power bodies.

This memo overviews the status, dynamics, and trends of Russian organized crime with particular attention paid to the criminalization of electoral processes by representatives of criminal groups. Throughout the 2000s, the leaders of some of these groups actively sought seats in regional and municipal power structures as well as in the national parliament. Once elected, these new officials have received procedural immunity from criminal prosecution for previously committed crimes and, quite often, have continued to engage in illegal activities. Various public officials have been prosecuted for their crimes and ended up behind bars, but others continue to straddle the criminal and political worlds without consequence. In this regard, it is necessary to raise awareness amongst voters of what is legal and illegal, as well as to accelerate the enforcement of federal laws that combat organized crime and a key common threat: corruption.

An Ineffective Fight Against Organized Crime

According to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), in 2016 there were 158 organized crime groups (OCGs) operating in Russia, including 24 ethnic-based groups, numbering about 3,500 individuals. However, these numbers relate only to the large OCGs that feature in the MIA records. The true numbers are certainly far larger. The extensive range of OCG activities includes extortion, assassinations, kidnapping (often of businesspersons), drug trafficking, prostitution, sales of counterfeit products (often alcohol), stealing vehicles, and a host of financial transgressions. The most common economic offenses are fraud, smuggling of strategic goods and resources (seafood, timber, antiques, wild flora and fauna), illicit trading, counterfeiting (of currency and credit cards), illegal gambling, and money laundering. The majority of OCGs are concentrated in the Central, Volga, North Caucasian, and Siberian Federal Districts of Russia, which is due to socioeconomic reasons and other characteristics of the population of these regions.[1]

Statistical analysis shows that it has become increasingly difficult to detect the activities of OCGs. According to the MIA, over the past nine years (2008-2017), the number of recorded crimes committed by OCGs has decreased fivefold, from 30,700 to 6,055, with the number of economic offenses decreasing from 18,300 to 4,315. In the context of all nationwide recorded crimes, OCG activity dropped from 0.9 to 0.2 percent. The number of crimes listed under Article 210 of the Criminal Code, “organizing of a criminal enterprise,” decreased by nine times, from 325 to 36.[2]

However, a reduction in recorded crimes does not indicate a decrease in the activity of OCGs. Rather, it demonstrates that such groups have increased their ability to conceal their crimes, often with the help of corrupt law enforcement officials. As an example, in April 2018, Mikhail Maksimenko, the ex-chief of the Investigative Committee’s Internal Security Directorate, was sentenced to 13 years in prison for taking bribes. According to the prosecution, he accepted $500,000 to release Andrey Kochuykov (an ally of notorious criminal leader Zakhar Kalashov) who was involved in extortion (for 8 million rubles or about $130,000) and a shootout at the Moscow restaurant Elements in December 2015. In March 2018, Kalashov and Kochuykov were each sentenced to about a decade in prison (for “two extortions committed by an organized group”).

The scale of corruption among Russia’s law enforcement is impressive. Over 2011-2016, several thousand police officers, 465 investigators, 97 prosecutors, and 26 judges were prosecuted for corruption.[3] There was no improvement in 2017: over 1,300 law enforcement officials were convicted of corruption, including 108 investigators, 19 prosecutors, and four judges.[4]

The ineffectiveness of the fight against organized crime is due to a number of factors, including:

- The abolition of MIA profile units (by the president in 2008) due to duplicative functions.

- The “humanization” of criminal legislation in 2003, 2011, and 2016 in the form of decriminalizing a number of activities (including financial), reduction of punishment terms, replacement of imprisonment with fines, and exclusion of confiscation of property from certain types of punishments.

- Incomplete police reform measures.

- Increased workload of policemen tasked with discovering and countering OCG activities.

- Lack of civilian cooperation with law enforcement. This is exemplified by a 2017 VCIOM opinion poll showing that 49 percent of victims did not report the crime to the police because they considered them to be incapable of providing assistance.

Criminalization of Power Bodies

Broadly speaking, the financial assets of criminal enterprises inevitably give them the potential to gain access to political power through corruption. As the economic influence of an OCG grows, its capability to corrupt electoral processes increases. According to the Russian Central Election Commission (CEC), from 2009 to 2012, the total number of candidates with previous convictions who ran for elected office increased 3.5 times, from 132 to 469. For the same timeframe, the number of candidates convicted of more serious crimes (at least ten years of imprisonment) increased 8.8 times, from 22 to 194. In 2013, there were 227 candidates with previous convictions, of these 150 were convicted of serious crimes. In the election campaigns of September 2014, there were 3,197 previously convicted candidates or 2.8 percent of the number of all nominated candidates. Among them were 593 persons, convicted of serious crimes and 76 for especially serious crimes. As a result, 520 candidates who had criminal records were elected.[5]

There are problems and concerns with the intersection of organized crime and official corruption at both the national and regional level. Both spheres have seen criminals becoming candidates on electoral lists. In 2016, in the federal lists of 14 political parties that participated in parliamentary elections, 138 criminal candidates were identified, 60 of whom did not provide information about their previous convictions.[6]

In order to penetrate officialdom, influential OCG operatives have altered their own or their candidates’ political affiliations, places of residence, last names and/or they removed information about their prior convictions from police databases. This allowed candidates to advance through the electoral process as seemingly law-abiding and respectable people. During their campaigns, they burnished their public image by offering to repair infrastructure, build playgrounds, distribute food to the needy, and organize charity or cultural events. They ran “normal” campaigns to earn votes and came across as sincere and authentic candidates.

Additional significant factors contributing to the criminalization of power structures include the marginalization of social consciousness, legal nihilism, and the political passivity of citizens. According to a 2018 VCIOM opinion poll, every third Russian citizen would be ready to vote for a candidate who has a prior conviction if his or her political program outweighs his or her past activities. Additionally, the Levada Center claims that one out of four citizens is ready to sell their vote in an election for a small amount of money (less than $100).

The latest criminal cases confirm that some regional elites have an interest in including OCG leaders in schemes to manage their districts. In other words, there exists a politico-criminal symbiosis of the corporate type. Officials view their status and available powers as an income-producing asset and their activities as a business that, in turn, is protected by the OCG they are affiliated with.

Countermeasures of Criminalization of Power Bodies

In order to counter the criminalization of political authorities, a 2014 Federal Law, “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation,” was introduced to implement the decisions of the Russian Constitutional Court that, since 2013, sought to limit the electoral rights of citizens who had serious criminal convictions. According to federal laws, citizens sentenced to imprisonment for serious crimes are not eligible to be elected to state and local bodies until ten years after the date of their crime’s removal from the criminal ledger. In the case of especially grave crimes, the time period is fifteen years. In reality, this would mean that only those who completed their sentences for serious crimes no later than 1999, and for particularly serious ones no later than 1992, should have been able to take part in the September 2017 elections.

Despite the introduction of legislation and the aforementioned anti-criminal electoral filter, the number of previously convicted candidates has not decreased. According to the CEC, in the election campaigns of 2015, there were 6,850 candidates who had criminal records (3.3 percent of the total taking part in elections).[7] This included 1,891 who had been convicted for serious crimes and 111 who had committed especially serious crimes. At the same time, 4,200 previously convicted candidates were registered. Among the elected were 1,800 with previous convictions. In September 2016, the deputy chairman of the CEC Nikolay Bulaev said that two deputies elected to the national parliament had criminal records. He stated: “In the federal lists on voting day, there were 55 convicted candidates who had no restrictions on passive electoral rights [the right to be elected]. The law allowed them to participate in elections.”[8]

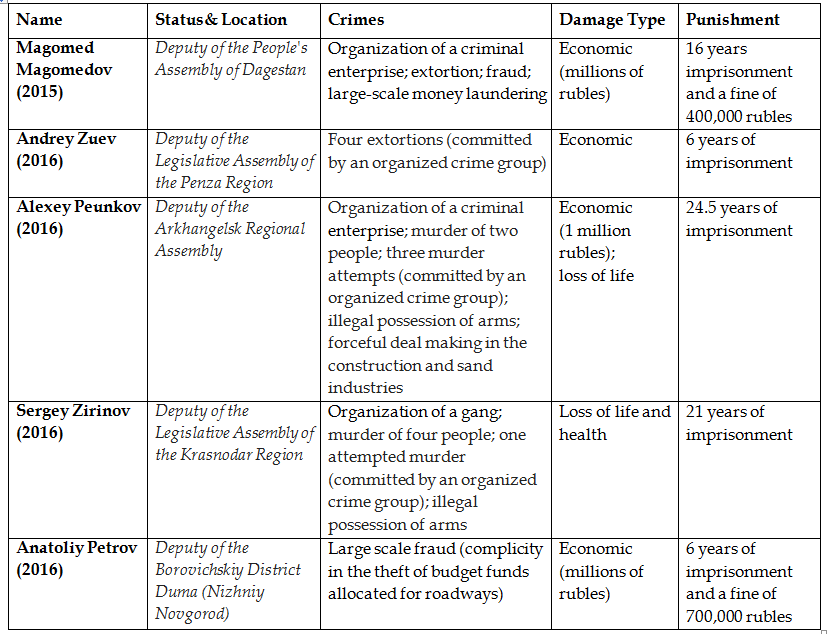

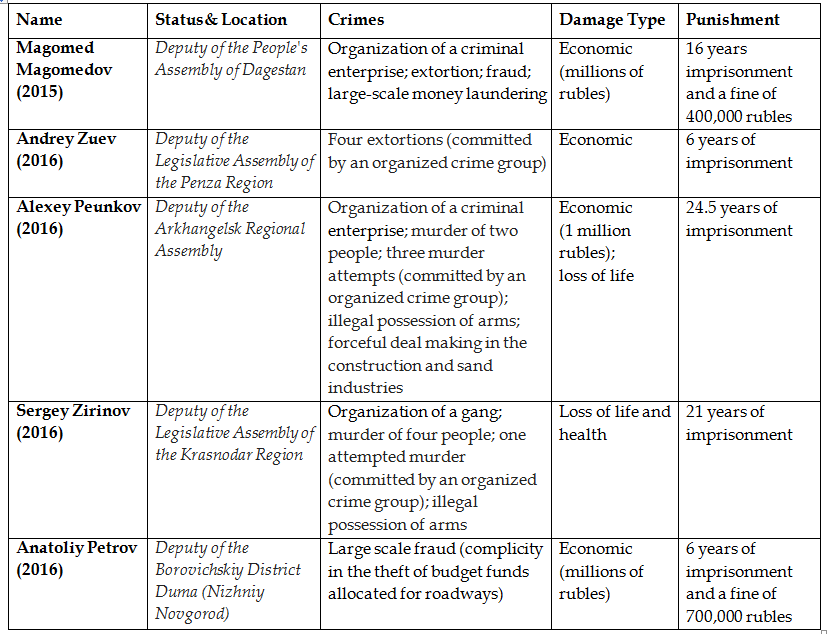

Ensuring that future lawmakers remain honest and not corrupt is by no means dependent on whether they have been convicted or not. According to the Russian Investigative Committee, over the past seven years, 1,313 municipal and 75 regional deputies have been prosecuted for corruption.[9] Some of them were convicted for organized crime (see Table 1 for most famous examples). In 2017, 12 regional and 96 municipal deputies were sentenced for corruption crimes (bribery, fraud, etc.).[10]

In order to prevent the falsification of election results, Russia adopted Federal Law No. 249 on July 29, 2017, which supplemented Article 142.2 of the Criminal Code that pertained to the “Illegal Issuance and Receipt of the Ballot for Voting.” The new addendum decreed, for instance, that if a member of an Election Commission was found to have issued an already-filled ballot to a citizen (so that he or she can vote for a pre-chosen candidate or vote twice), he or she would face a fine of 200,000-500,000 rubles ($3,200-$8,000) or imprisonment for up to four years. The person who cast the sham vote would face a fine of 100,000-300,000 rubles ($1,600-$5,000) or imprisonment of up to three years. If the crime was committed by an organized group, its members would face fines from 400,000-700,000 rubles ($6,000-$11,000) or imprisonment of up to five years. Before, for such manipulations, the law called for only an administrative fine of up to 50,000 rubles ($800).

However, the attempted enforcement of criminal liability of election officials is unlikely to lead to an increase in criminal cases. According to the Criminal Procedure Code, members of the Election cCmmission are referred to as so-called special subjects and the decision to initiate a criminal case against one of them is made by the heads of the Investigative Committees at the regional or federal levels. For this reason, the number of criminal cases against election officials remains insignificant. In 2013-2017, for example, only 25 people were convicted of falsifying election documents or for incorrectly counting votes, and 33 people were convicted for falsifying voting results. Almost all of them only received fines.[11]

Conclusion and Recommendations

The power of elected officials and the nature of their decisions directly affect the rights and freedoms of ordinary citizens. An official with criminal connections has reduced objectivity in the performance of their duties, which harms the legitimate interests of citizens and organizations. In this regard and when there is more than just a handful of isolated cases, the criminalization of elected bodies poses a serious threat to national security.

The following policy recommendations are offered in order to reduce the criminalization of electoral processes by criminal enterprises:

- Accelerate the adoption of federal laws and long-term programs meant to combat organized crime.

- Increase the activities of law enforcement bodies so they can liquidate known criminal enterprises, particularly those with international ties.

- Increase the effectiveness of the fight against corruption. The current fight against bribery and fraud, which prevails in the total volume of registered crimes, does not correspond to the scale and level of the threat since it does not affect high-ranking officials responsible for making important management decisions. (This aligns with the assessments of Transparency International (TI) and the Global Economic Forum.)

- Raise the legal awareness of voters. It is important that voters know that electing a person with prior criminal convictions is dangerous to their livelihoods in direct and indirect ways, and to the functioning of the Russian civil services, which are meant to serve them.

Striving to remove a) prohibited candidates from lists and b) criminalized authorities at the regional and municipal level should be a top priority of the recently re-elected president, Vladimir Putin, and his newly seated administration.

Table 1. Most Famous Regional Criminal Cases of Elected Russian Officials Found Guilty of Associating with Organized Crime

Source: Supreme Court of the Russian Federation

Alexander N. Sukharenko is Director of the Center for the Study of New Challenges and Threats to the Russian Federation, Vladivostok, Russia.

[PDF]

Homepage image: previously convicted Duma Deputy Evgeniy Surnin (Rezh, Sverdlovsk) who has a spider tattoo on his head.

[1] Annual report of MIA activity for 2016.

[2] Annual report of MIA on organized crime for 2008-2017.

[3] Annual Report of the Russian Investigative Committee activity for 2011-2016.

[4] Annual Report of the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation in the anti-corruption sphere for 2017.

[5] Report of the Control and Auditing Service under the CEC of Russia for 2014.

[6] Report of the Control and Auditing Service under the CEC of Russia for 2016.

[7] Report of the Control and Auditing Service under the CEC of Russia for 2015.

[8] Report of the Control and Auditing Service under the CEC of Russia for 2016.

[9] Annual report of the Russian Investigative Committee activity for 2011-2016.

[10] Annual report of the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation in the anti-corruption sphere for 2017.

[11] Annual report of the Supreme Court of Russia for 2013-2017.