Russia has recently intensified its efforts to improve its image in Berlin, one of the most important of European capitals. The multiple cultural events at the end of the 2012 sponsored by Russia, including of course Gazprom, were meant to foster cultural diplomacy, and not [quite] as an extension of soft power.

The difference between the two concepts is crucial. Cultural diplomacy is simply a unilateral demonstration of country’s artistic talent while soft power presupposes forging a system of interactive communicative relations with other nations that are ideally conducive to shared norms, if not values.

Russia’s cultural diplomacy in Berlin has two tracks. One is basically meant to reach Russian-speaking audiences that are nostalgic for the motherland. Russian Film Week (which includes showing new movies), theatrical performances (with Moscow celebrities such as actress Chulpan Khamatova, and literary discussions (as with writer Dmitry Bykov) highlighted popular Russians. The selection of figures was politically balanced. Chulpan Khamatova runs a charity fund and is known for her work with Kremlin activities. Dmitry Bykov is one of the most sarcastic critics of the ruling elite, which he openly mocks in his highly popular pieces that are widely available on the Internet.

A visible signs of political context is an exposition photographs of Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency, which many Germans could see as a nostalgic allusion to a bygone enthusiasm for modernization, partnership, and security dialogue. There is also a historical discussion of Russia’s victory over Napoleon, which also fits nicely with the Kremlin’s narrative.

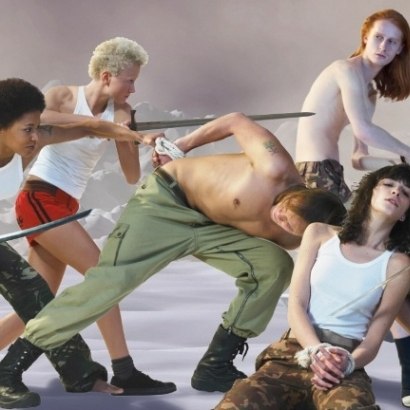

The second track of Russia’s cultural diplomacy is meant for wider consumption. Two events in this regard are of particular interest. One is the historical exhibition “Russians and Germans” in one of the best downtown museums. The second is a video art installation performed by Russia’s AES+F group. The two events are strikingly dissimilar. The exposition is a rather traditional display of Russian–German relations starting from the times of the Hanseatic Union. Each event is placed within a certain logic of historical continuity. On the contrary, the installation introduced a futuristic and absurdist world of post-modern imagery, with people fighting and killing each other for no rational reason. It shows technological disasters as part of ordinary everyday life.

There was another strange aftertaste of absurdity I experienced while at the concert hall where the aforementioned Dmitry Bykov performed his events. How otherwise one can feel about the showing of an apologetic book on Mikhail Khodorkovsky—this at a state-sponsored international cultural festival. The Russian state imprisoned its richest challenger and then is selling a book that morally rehabilitates him. Russia brings to Berlin artists like Dmitry Bykov only to hear from them that Russia is a wild country ruled by crooks and blockheads.

The same irony can be said for the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation, one of the co-sponsors of the Russian Festival in Berlin. Prokhorov himself was an object of harsh mockery in Bykov’s show. Is it because of the Kremlin’s impartiality, a feeling of superiority, or simply insensitiveness to discourses that it doesn’t view these fragmentations as dangerous?

After such public paradoxes, it may not be unreal to see Pussy Riot as an element of Russia’s cultural outreach. This radical gesture may be closer to soft power than anything else.

Andrey Makarychev is a Guest Professor at the Free University of Berlin, blogging for PONARS Eurasia on the Russia-EU neighborhood.