(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Accumulating evidence points at prospects of growing destabilization at the regional level in Russia. In 2019, five consecutive years of economic stagnation ignited a wave of protests across the country. In 2020, as Russia’s economic situation worsened dramatically due to a pandemic-driven halt to economic activity combined with a fall in oil prices, support for Kremlin appointees might start crumbling as well.

What does it mean for Russia’s September 13 nationwide elections, when residents of 18 regions will elect governors and for which early voting has just started? In an analysis of factors that have contributed to victories by pro-Kremlin candidates in gubernatorial elections in 2012-18, working with Russian electoral statistician Vladimir Kozlov, we find a positive correlation between the dynamics of real disposable incomes and pro-Kremlin candidates’ vote. The crisis-induced decline in real disposable incomes in the second quarter of 2020 raises risks that the Kremlin’s appointees will fail to get reelected in several regions. Aware of these prospects, the authorities have recently passed new legislative amendments that further limit independent candidates’ ability to participate in elections (such as more obstacles for election monitoring). As a result, the September 2020 elections are taking place under what some observers have described as the worst legislative regulation of the electoral process in Russia in the last 25 years.

Why Russia’s Regions?

In 2019, growing dissatisfaction with the political system in Russia ignited a wave of protests that spread across all but two of Russia’s regions. The protests, which commonly targeted federal authorities, spanned regions from Moscow, Arkhangelsk, and Yekaterinburg to Kalmykia and Ingushetia. This trend deepened in 2020. In mid-July, the rallies that started in the far eastern Russian city of Khabarovsk against the arrest of Governor Sergei Furgal and political repression in the region became the largest in size (up to 10 percent of Khabarovsk city residents took to the streets) and the longest in duration—over 50 protest actions took place in Khabarovsk between mid-July and the end of August 2020.

What role does the regional economic situation play in this dynamic? Overall, observers have been reluctant to link economic explanations to protest propensity in Russia. Most of the recent protests across Russia had a non-economic agenda with topics ranging from the environmental situation in the regions to political and civic demands. However, while specific triggers of most local protests are not economic, the economic situation may be creating a background against which any disappointment can provoke a large protest. Our research demonstrates that the decline in real disposable incomes contributes to lower support for federal authorities at the regional level.

The elections of regional governors are interesting for several reasons. First, Russian regions provide substantial variation of political regimes at the subnational level despite similarities in political institutions, ideological and historical legacy, and enough data for quantitative analysis. Second, regional dynamics often mirror and even anticipate federal processes in Russia. For example, in the early 2000s, the turn toward authoritarian practices on the regional level reinforced the nationwide trend of tightening control over political processes. And, finally, as Moscow was overflowing with money in recent years, since 2015, Russia’s regions have increasingly signaled trouble due to the dire economic situation and the federal government’s decision to shift responsibility for executing presidential decrees on wage increases to the regional level. This suggests that deterioration of the economic situation is more pronounced on the regional level, and their political dynamic may be more responsive to the country’s economic dynamic.

Economic Voting in Russia

Scholarship on the impact of perceptions of the economic situation on vote preference in Russia has uncovered some evidence of economic voting. For example, Daniel Treisman finds that President Vladimir Putin’s declining popularity in 2011 reflected stronger economic concerns, as those who saw economic weakness became much less supportive of the Kremlin and appeared to have increasingly blamed their political leaders for unsatisfactory economic and political outcomes. Similarly, rising economic concerns in light of a long-term reduction in the real disposable incomes of Russians may be connected to the ongoing decline in Putin’s approval rating.

As a result of the worsening of the economic situation combined with a widely unpopular retirement age increase in mid-2018, in the September 2018 gubernatorial elections, pro-Kremlin candidates received the lowest support in many years. In seven out of 22 regions, pro-Kremlin candidates won the elections with an overall result below 60 percent (over the period of 2012-17, there were only seven such outcomes). In four of them, a runoff was needed to determine the winner despite most predictions. For the first time since 2012, in the 2018 elections, the incumbent governors of two regions (Khakassia and the Khabarovsk territory) lost to representatives of the systemic opposition, even though these leaders had easily won previous elections in 2013. Do such devastating results for Kremlin candidates correlate with the regional economic situation? Zubarevich found no connection between the income dynamics of the population and the 2018 gubernatorial election results, concluding that the decline in the population’s incomes likely created a negative backdrop but did not trigger protest voting. However, her study only focused on the 2018 election. Our study with Kozlov allows us to address this question in a more systematic fashion by exploring all rounds of direct gubernatorial elections since 2012.

Key Findings

The elections of regional leaders (governors) in Russia were originally introduced in 1991, became nationwide in 1996, but then were abolished in 2005. In 2012, on President Dmitry Medvedev’s initiative, direct gubernatorial elections were reinstated (although subsequently 10 out of 85 Russian regions replaced them with votes in regional legislatures).

What factors contribute to voting for pro-Kremlin candidates in gubernatorial elections? To address this question, we ran a study of the Russian regions designed to evaluate the impact of the real disposable income decline on support for pro-Kremlin candidates in gubernatorial elections. We compiled a dataset of first-round elections of regional leaders (governors) since 2012 with a total of 109 observations.

As a dependent variable, we took the percentage of votes for a candidate backed by the federal government in a given region’s gubernatorial elections during the 2012-18 period. For the dynamics of the regional population’s real disposable incomes (as a percentage of this index in the previous year), we used Russia’s Federal Statistics Service (Rosstat) estimates of real disposable incomes taken as an average of these indexes for two years preceding the election year. Other controls included in the analysis were electoral turnout, the number of candidates in the election, belonging to the United Russia Party, being born in the region, the share of large/small businesses, the share of the urban population, the rate of unemployment, and the share of votes for Putin/United Russia in preceding elections on the regional level. We used ordinary least squares with standard errors clustered by region.

As a result of our analysis, we have found a substantial and statistically significant correlation between the dynamic of real disposable incomes in the region and support for the pro-Kremlin candidate in the gubernatorial elections. The established correlation between support for the pro-Kremlin candidate in a given region and the dynamics of disposable incomes suggests that the social and economic situation in the Russian regions has a significant impact on public support for federal candidates. One can hence expect that further deterioration of the economic situation in the country will create more electoral risks for the Kremlin.

Another interesting finding in our report is that “outsiders” (candidates who are not born in a given region) tend to do better in gubernatorial elections than region-born candidates. This finding is echoed by the Kremlin’s current policy of appointing in the region people without a long history within and familiarity of the region. In recent years, the Kremlin imposed a high degree of rotation in regional leadership. This is an absolute record for the last nearly 30 years and is only comparable to the Gorbachev era, when the first secretaries of the Communist Party’s regional committees were replaced similarly en masse.

One reason for such policy is that candidates without “negative history” in a given region are a clean slate that usually allows for greater public support. Another reason is that under continuous economic stagnation and rising risks of losing control over regional elites, appointing “outsiders” not associated with the local elite and fully dependent on Moscow may allow the Kremlin more significant control over appointees.

Kremlin Responses to the Adverse Trend

In 2020, Russia’s economic situation worsened dramatically. A halt to economic activity resulting from the coronavirus pandemic combined with a fall in oil prices has caused a sharp decline in living standards. Twice as many Russians have reported wage delays, cuts, or layoffs in May 2020 as compared with October 2019. This led to the sharpest drop in Russians’ assessments of the economy since the 2008 crisis. By March 2020, even before regions imposed coronavirus-associated lockdowns, the consumer sentiment index in Russia declined by 20 points—the sharpest drop on record since the 2008 crisis, reaching by August 2020 the lowest point in eight years. In the second quarter of 2020, Russian GDP decreased by 8.5 percent compared to the same period of 2019, and even by Rosstat’s official estimates, real disposable incomes declined by 8 percent, setting the record since 1999. Simultaneously, the propensity to protest increased, reaching its 2-year peak in July 2020. As our findings suggest, the incomes dynamic may directly translate into lower voting results of pro-Kremlin candidates in the gubernatorial elections set to conclude on September 13, 2020.

Aware of growing electoral risks, the Kremlin passed a series of legislative amendments ahead of the September elections that have resulted in what some observers have described as the worst electoral regulation in Russia in the last quarter-century. The number of registration obstacles for opponents to be allowed to run against Kremlin candidates has increased dramatically. For example, new amendments banned from running in elections people convicted under several dozen new articles of the Criminal Code, such as those convicted for violations of the procedure for holding a protest rally.

This allows the authorities to eliminate dangerous competitors by condemning them on trumped-up charges. The procedure for registering candidates based on the signatures of voters has also become more complicated by reducing the permissible share of marriage in them from 10 to 5 percent. A recent report has estimated that in 2020 the number of candidates not allowed into the race in the election under various pretexts will reach its peak since 2016. With such a registration system, 9 out of 10 candidates from parties that do not have prior arrangements with the Kremlin will fail to reach the ballot in 2020.

Ultimately, the recent poisoning of Alexey Navalny suggests one way to reduce political competition in Russia. The opposition leader and his team were developing Smart Vote strategies in several regions in the September 2020 elections. This strategy seeks to unite opposition votes behind candidates most likely to defeat pro-Kremlin candidates, and it helped non-Kremlin candidates win 20 out of 45 single-member constituencies in the 2019 Moscow Parliament Election. Navalny was poisoned as he was returning to Moscow from Tomsk, one of the regions where his Smart Vote campaign is set to take place.

Along with eliminating almost any electoral competition, the authorities used additional tactics to boost the vote for pro-Kremlin candidates. Given the low ratings of the United Russia party, many pro-Kremlin candidates now tend to be self-nominated instead of being (put) on the United Russia ticket. The Kremlin has also continued to use leadership rotation within the gubernatorial corps. In the run-up to the 2020 gubernatorial elections, incumbents have been replaced in 9 out of 18 regions. However, the Kremlin’s policy of ceaseless rotation of the elites may also eventually result in the depletion of its personnel resources.

The May 2020 legislative amendments have also allowed for electronic voting in all elections, which prevents independent observers from monitoring how votes are cast and counted. In addition, the Central Election Commission has received significant freedom in determining the procedure and timing of early voting. As a result, September voting is taking place over the course of three days, from September 11 to 13, instead of one. The multi-day voting complicates the ability of independent observers to monitor the elections and ensure a lack of fraud, as demonstrated by the recent voting on the constitutional changes held from June 25 to July 1, 2020. If that was not enough, yet another set of legislative amendments that came into force on July 31 now limits who can become an observer in regional and local elections to only those citizens who are registered in the region.

What Does It Mean for the 2020 Elections?

In 2019, eliminating competition helped the Kremlin’s appointees win elections. However, despite the unprecedented level of restrictions and repression imposed in 2020, the risks for the authorities are bigger this time around given the combination of the economic crisis and the fact that many regions that are less “favorable for the Kremlin” will hold elections this cycle. Several of the most protest-prone regions are set to elect Kremlin appointees in the September voting, including Irkutsk (the only region that did not elect a Kremlin appointee out of all the regions that held gubernatorial elections in 2012-17), Komi Republic, and Arkhangelsk (where large protests erupted in 2019). Analysts predict that at least three regions might fail to elect a pro-Kremlin candidate in the first round of the September 2020 elections.

In short, risks on the regional level are growing for the Kremlin, as socio-economic problems continue to accumulate. The September regional and local elections are also considered a testing ground ahead of the scheduled 2021 State Duma elections in Russia, which are of utmost political significance for the Kremlin. While the Kremlin and local governments have intensified restrictions and repression to reduce their electoral risks, this approach may fail to deliver at least in several regions where the elections are set. Two developments seem inevitable: the upcoming elections will be among the dirtiest in Russia’s post-Soviet history, and they will set a trajectory for the Russian electoral system for years to come.

Maria Snegovaya is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at George Washington University.

[PDF]

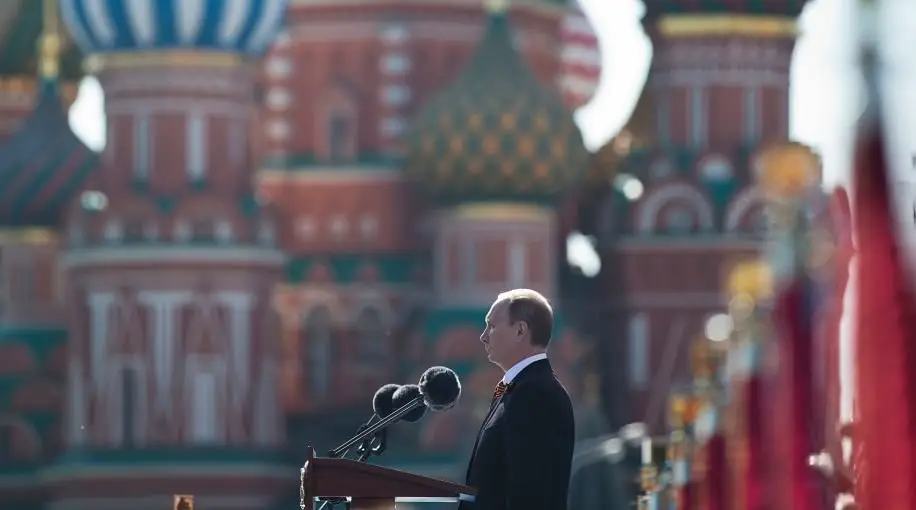

Homepage image credit: Shutterstock-9534313d