(PONARS Policy Memo) Most experts recognize anti-Americanism as a pillar of the patriotic discourse that has risen during Vladimir Putin’s third term as president. One of the main reasons for this high level of anti-Americanism (and its periodic sharp spikes) is that the Russian government has made available, if not absolutely encouraged, ideological scripts that are echoes of the Cold War era. Performances organized by the Russian hyper-patriotic biker club Night Wolves stand as prime examples of the Kremlin’s new take on old propaganda efforts. Their spectacles tend to display the full gamut of the Kremlin’s imagery and messaging, from the evil of the United States and Ukrainians to the glorification of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian military.

An analysis of Night Wolves spectacles reveals how the Kremlin’s agent provocateurs make use of the fuzzy lines between patriotism, pro-Putinism, Russian Orthodoxy, civic/national duty, and militarism. The purposes of these anti-American scripts are many, not least of which is to garner psychological and physical support for the motherland one way or the other, especially during the Euromaidan era, but also to create a sense of Russian identity, which has been vacuous since the early 1990s. The alarming aspect is that these types of fantastical attractions can transform patriotic attendees into actual networks of gun-toting Russian combatants, which may be part of the government’s objective.

Exploiting Anti-Americanism

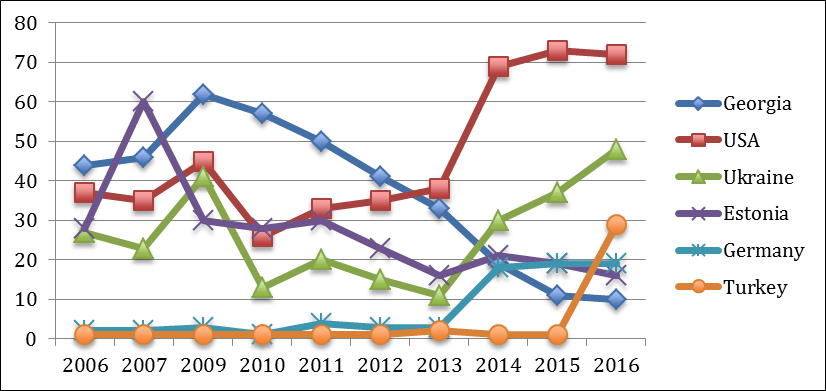

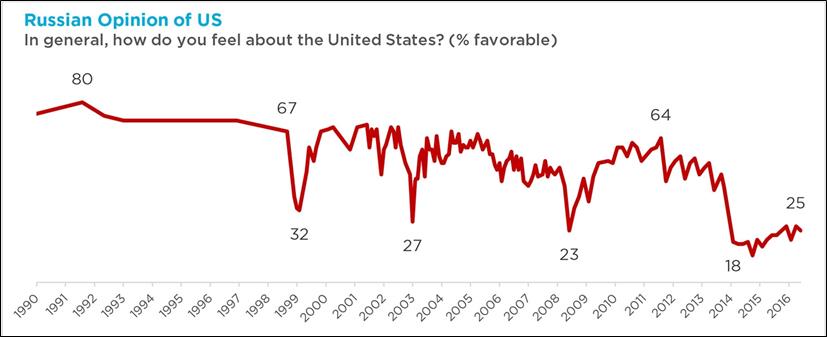

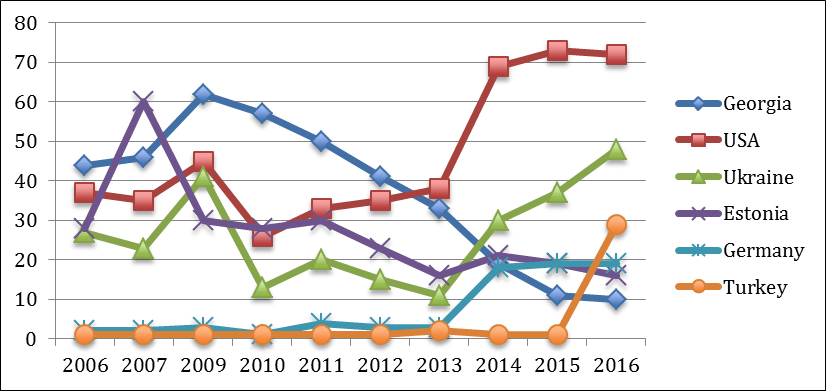

According to a poll by the Moscow-based Levada Center, anti-American feelings in Russian society tend to peak when the government perceives negative geopolitical changes in Europe and when Russia’s interests in its near abroad are challenged. As Table 1 shows, the lowest levels of friendly attitudes toward the United States were registered in 1999 during the NATO campaign against Serbia in Kosovo, in 2003 during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, in 2008 during the Russia-Georgia war in August, and in 2014 during the Euromaidan in Ukraine and ensuing conflict.

Table 1. Russian Opinion of the United States

Russians tend to blame the United States for a range of troubles, both domestic and international. Public opinion polls show that Russians consistently tend to accuse the West of fomenting so-called color revolutions in post-Soviet states and of causing the current split between Russia and Ukraine. Certainly, successful Russian state-controlled propaganda campaigns have influenced domestic perceptions about a range of international actors. In May 2016, the Levada Center conducted a survey that demonstrated a correlation between major international events (from Russia’s perspective) and public distrust toward the countries involved (see Table 2). Clear examples of times of high Russian public negativity toward other states were during the Euromaidan protests, the Russian-Georgian war, and the relocation of a World War II monument in Estonia (the “Bronze soldier affair”).

Table 2. Top Five Most Unfriendly/Hostile Countries (Ranked by Russians, May 2016)

For many Russians, the apparent irrationality of the military conflict in Donbas can only be explained through the external factor of pernicious U.S. influence in Ukraine. A leading piece of evidence that showed up frequently in pro-Kremlin newspapers, blogs, and television shows consisted of photos of former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland distributing snacks to Euromaidan activists in February 2014 (see the image in the PDF version). This type of imagery has been repeatedly reproduced in Russian popular culture in recent years with the aim and effect of vigorously crystallizing phantasms and stereotypes of the national consciousness.

The Night Wolves and the “Dangerous” Rock Band

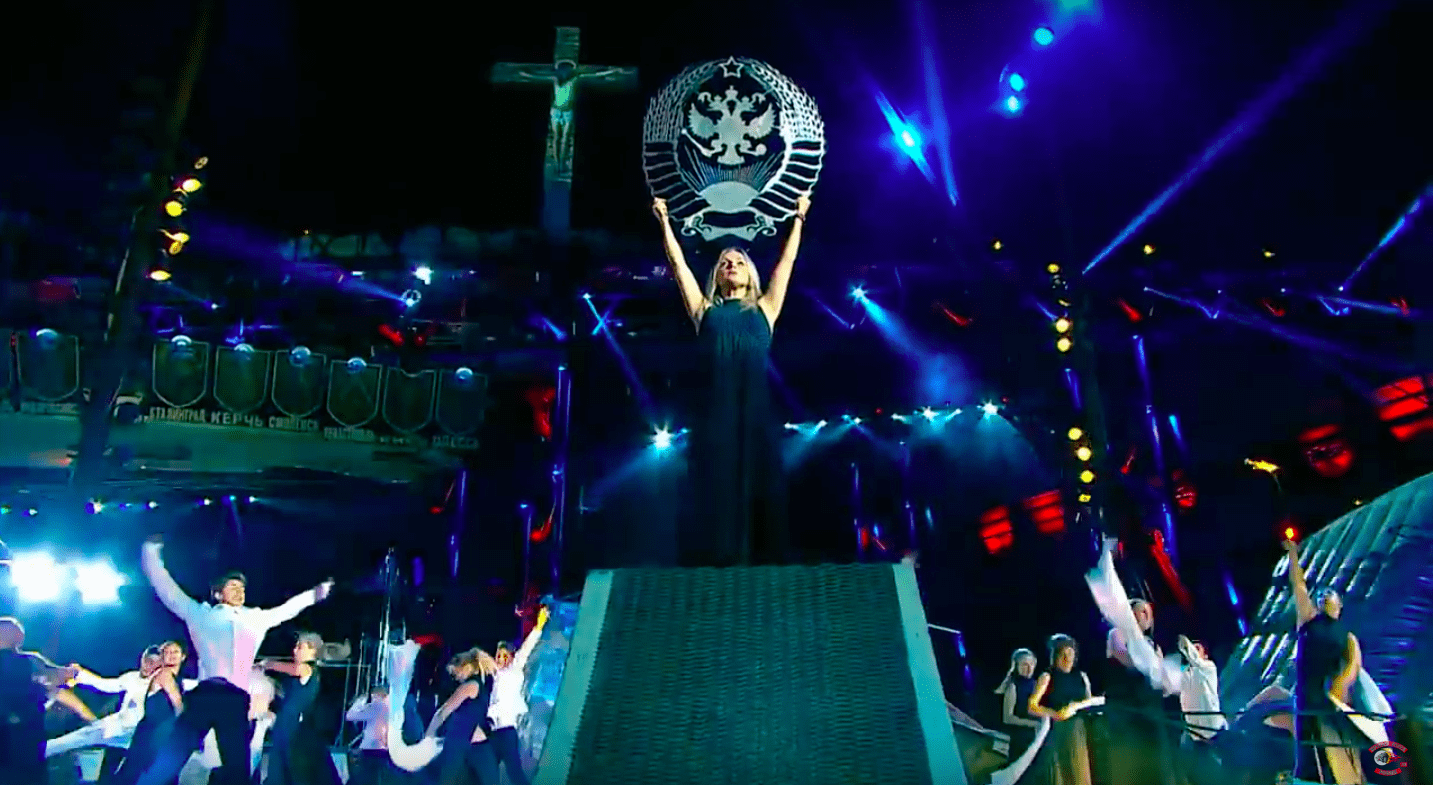

Homegrown images and events can also be highly serviceable for the Russian state’s national idea. The large-scale historical-patriotic performances by the Kremlin-patronized Night Wolves bikers club since 2010 perhaps best reflect all of the permutations of the state narratives. The club has been supported by multimillion-ruble grants from the Presidential Administration (until 2017). Their spectacles often have focal points involving state-sanctioned geopolitical imagery and have been broadcast on state television channels. The ideological scripts that undergird their performances are apparently derived from Aleksandr Dugin’s Eurasianist and Russian messianic conceptions. The shows are lavishly garnished with Russian Orthodox themes and nostalgia for former imperial glories (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Scene from the Night Wolves’ “Forge of Victory” Show (2015)

A performer holds up a modified state emblem of the Soviet Union in which the hammer and sickle are replaced by the two-headed eagle referencing the Russian Empire. There is a large Christian cross in the background. (Source: YouTube)

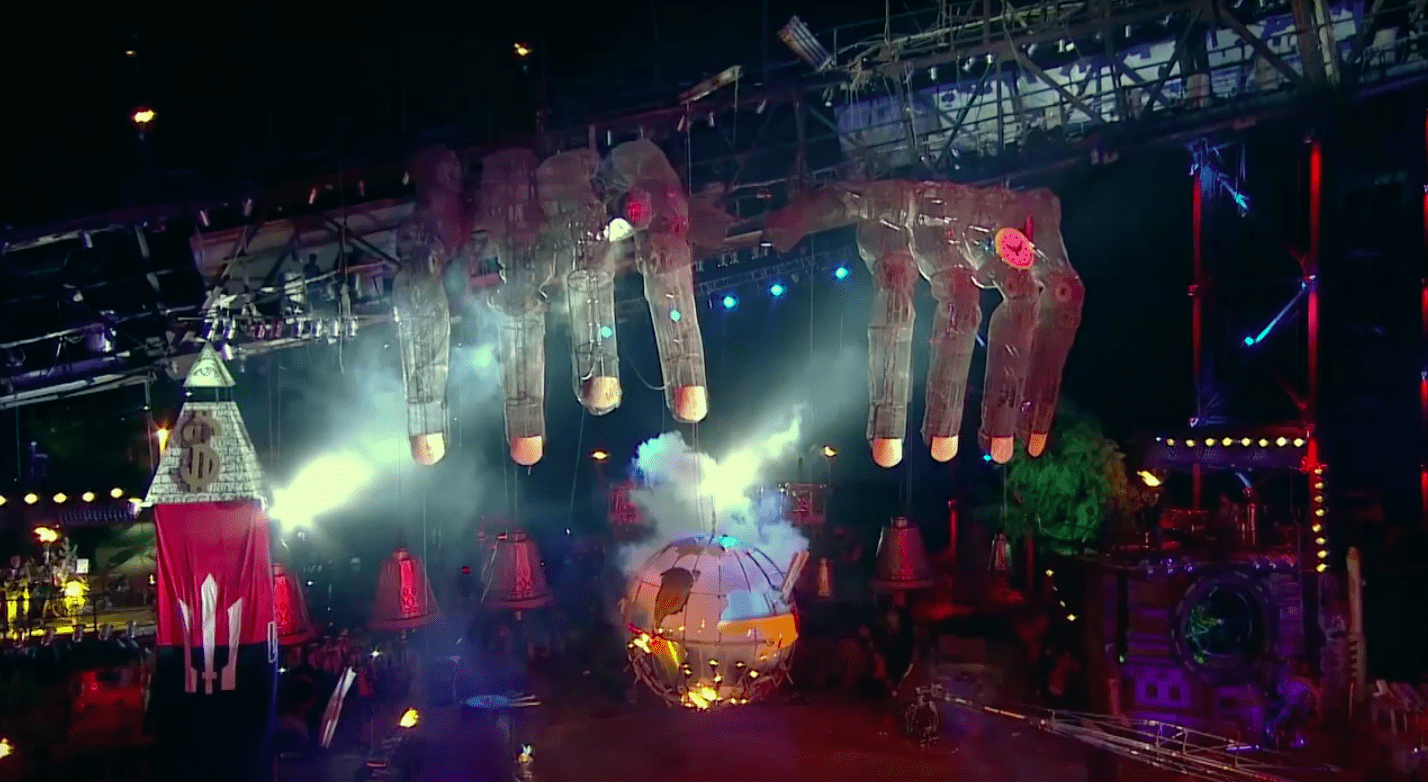

A good example of anti-American imagery can be seen in the Night Wolves’ 2014 show “Redemption” where the United States is portrayed as the world’s evil puppet-master manipulating the strings of nations and geopolitical events. In the show, gigantic hands loom threateningly over everyone (seen Figure 2). Others segments show Ukraine bleeding, which is a flashback to the familiar Soviet-era cliché about the “sticky fingers of capitalism” (“zagrebushchie lapy kapitalizma”).

Figure 2. A Scene from the Night Wolves’ “Redemption” Biker Show (2014)

(Source: YouTube)

However, despite all of the alluring emotional attributes of the shows, the prominence of Cold War-style anti-American elements actually speaks of the profound absence of ideological alternatives to the West as Russia’s archenemy.

The imagery can obviously no longer rest on the binary communism-capitalism contest because Russia has been well on the path of free-market capitalism since 1991. In this regard, the heavy use of Cold War-era “stock” narratives should not confuse us into thinking that these efforts are somehow aimed at reviving Soviet ideology. Instead, this conceptual shallowness manifests itself in the use of the corporeal language in which categories of the geopolitical order are described. An example would be in gender relations, where there is clear emphasis on Russia having a masculine, hegemonic position. As seen from this perspective, and as captured in the performance of the songs “Amerika,” “Maidan,” and “Betrayal” by the Russian patriotic band “Dangerous” (“Opasnye”), the United States is represented, in one Night Wolves skit, as a woman in a bikini top that is made out of NATO armor and whose irrational behavior is due to “menstrual hysteria.” She (the United States) is portrayed as a loser who desperately wants to be cool and capable.

The leader of Dangerous, Gleb Kornilov (see Figure 3), is a regular participant at Night Wolves shows. He was also the force behind the “Save Donbas” charity fund and was one of the main supporters among Russian musicians of the (unsuccessful) Russian “Novorossiya” project in eastern Ukraine.

Figure 3: Gleb Kornilov, Leader of Dangerous, Performs at the 2015 Biker Show

Kornilov’s shirt says “Columbus, Shut Down America.” (Source: YouTube)

Kornilov’s lyrics provide examples of the anti-Western outlook spread through Russian pop culture. Here is an excerpt from his song “Betrayal”:

Europe and America / You’ve probably rushed / To take history’s mantle / From Russia’s shoulder / You can’t forgive us / That our land is vast / The Russian spirit married / To the Russian landmass! / And burning in envy / You decided to become us / But Gagarin’s flight / Exposed your weakness / And you won’t rewrite / The year 1945! / And while you breathe angrily down our necks / We march forward.

In just this small passage of lyrics, some of the main aspects of Russia’s self-aggrandizement are apparent. Recurring themes include Russia’s incredibly vast territory, military victory over the Nazis in World War II, and pioneering of space exploration. The merits of this genre are generally funneled to demonstrate Russian superiority over the United States.

Despite the Soviet Union’s collapse, the propaganda employed in the Night Wolves shows uses Soviet-era discursive schemes in which Russia is again pitted against the West. Often Soviet ideology is replaced by Russian Orthodox values, which is usually juxtaposed against the West’s decadence—a narrative that replaces Moscow’s Cold War-era clichés about “rotten capitalism.”

A persistent problem is that despite years of narratives and imagery, it is still unclear what the current Russian national idea is. This representational trap in Russia’s national geopolitical consciousness could be explained in psychoanalytical terms as attempts to attain a perceived lack of identity. Seen from this perspective, the situations in Crimea, Ukraine, and Donbas all function, as French intellectual Jacques Lacan would say, as objects whose recapturing promises restoration of an imaginary full identity of the Russian nation. In this context, the construction of new fantasies becomes an inevitable component of popular “cultural” geopolitics. One of the main aims of this is to stabilize Russians’ mainstream worldviews through dramatic oversimplification and emotional delivery.

Conclusion

The anti-Americanisms in the Night Wolves’ shows and songs by Dangerous represent compelling examples of how Moscow’s policymakers use culture as hybrid policy tools. Putin personally patronized this biker club for many years, which in the Russian political context, is more than a green light to continue doing what they do. The shows and songs focus on delivering patriotic messages to domestic audiences and include imagery and commentary on Russia’s relations with the United States and key orbital countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, United Kingdom, and Germany.

Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the Night Wolves is that some of their members participated in the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine. This blurs the line between propaganda—and a highly exaggerated one at that in terms of rock concerts—and actual military activity. In this way, the Night Wolves are a product of the Kremlin’s “political technologies.” Through these types of cultural phenomena, Russia’s leadership seeks to boost patriotism, provide the foundation for a new genus of Russian identity, and, in a subtle way, shorten the distance between enjoying entertainment to being recruited into combat-defense roles of the motherland.

Alexandra Yatsyk is Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Uppsala University, Sweden.

[PDF]