► The emergence of permanent history parks in Russia can be compared to the advent of “Institutes of National Memory” that operate in a number of former Soviet and Central European states. The vision of history they present is highly politically engaged.

History as an Ideological Tool

By Ivan Kurilla, European University at St. Petersburg

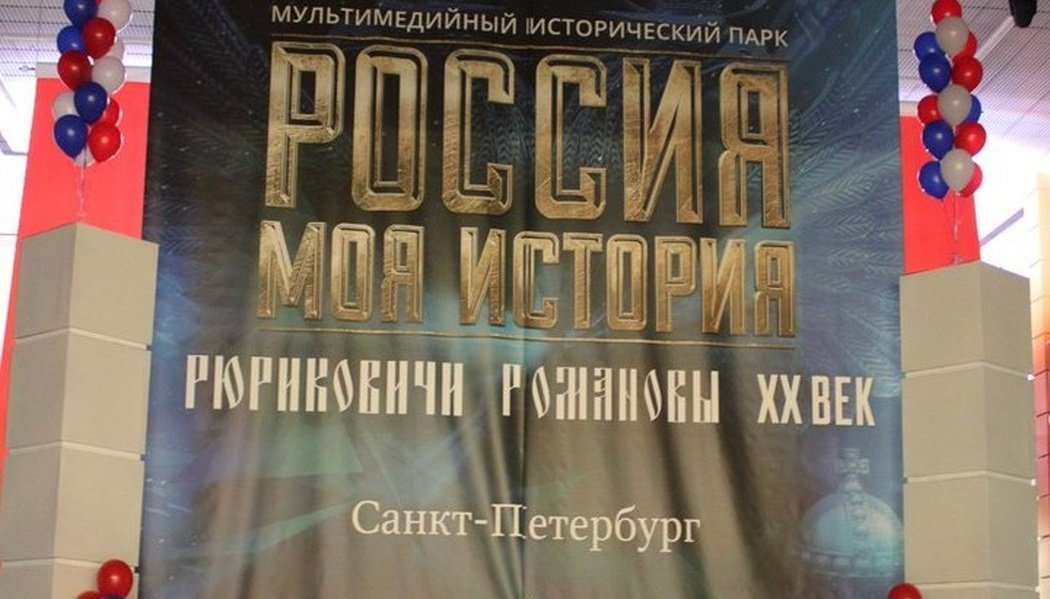

Marlene Laruelle, in her recent piece for Point & Counterpoint, provided an excellent overview of that new-old actor on the Russian history market, the Russian Orthodox Church, which has over the past two years produced a network of “Russia: My History” multimedia exhibitions in many Russian cities.

At present, the list of parks that have been opened includes Moscow, Volgograd, Ekaterinburg, Kazan, Makhachkala, Nizhnii Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Perm, Samara, St. Petersburg, Saratov, Stavropol, Tyumen, Ufa, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, and Yakutsk—a total of 17 cities. The project website lists four more parks as being under construction, and even more are planned (the total number will soon be 25, according to many statements).

|

“The parks’ narrative is clearly anti-Western, anti-liberal, and statist, and projects Russia’s current political cleavages back onto history.”

|

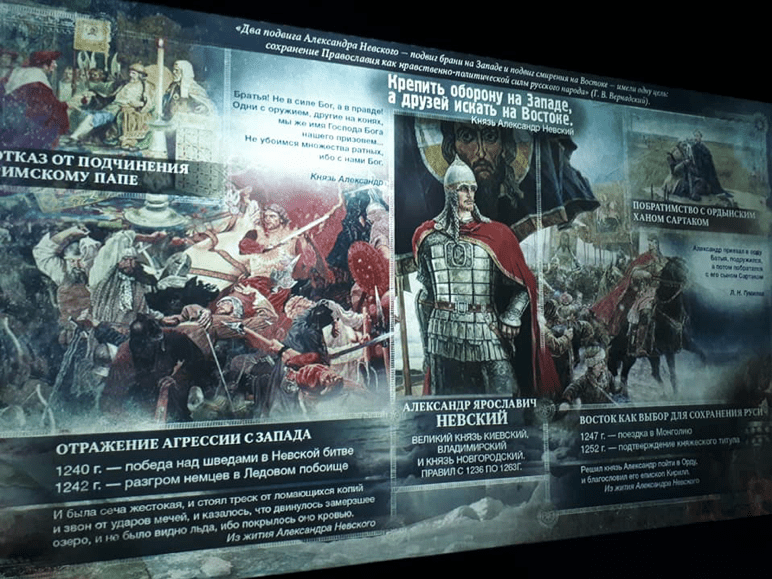

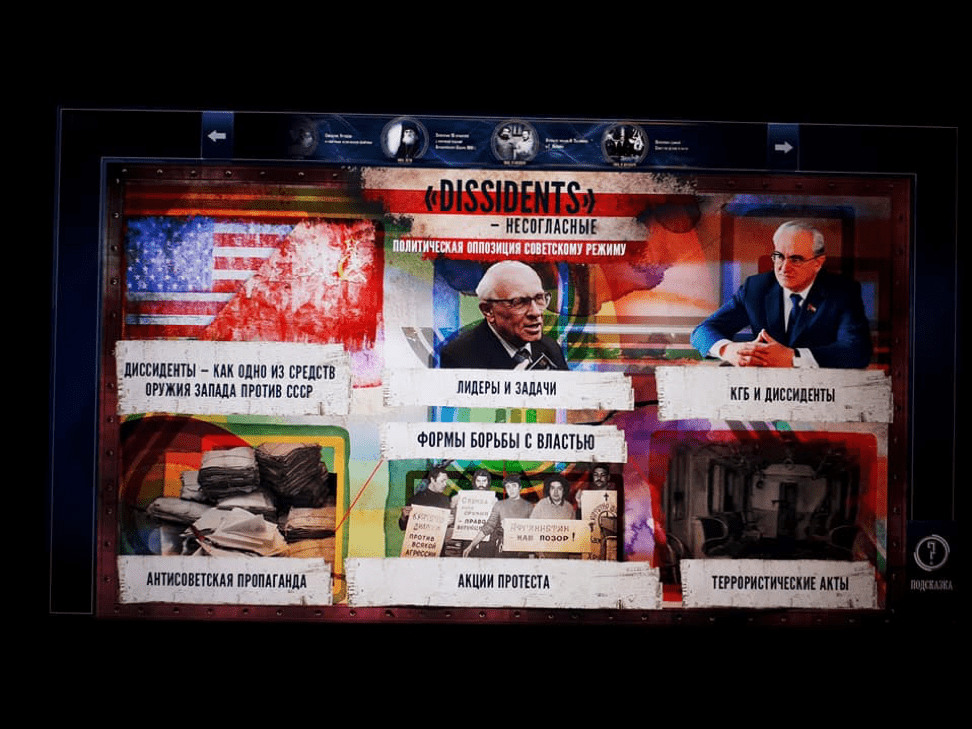

First of all, I would add some details about the parks’ narrative. It is clearly anti-Western, anti-liberal, and statist, and projects Russia’s current political cleavages back onto history. Thus, the authors of the content describe one of the most successful medieval princes of Rus, Daniil Galitsky, as a pawn of “oligarchs,” and paint his country as being betrayed by its European neighbors, who first installed their agent as a prince and later absorbed the country altogether. (The name of the country is presented in blue and yellow, the national colors of contemporary Ukraine.) By contrast, Alexander Nevsky is shown as a wise ruler whose motto was “fortify defenses in the West and search for friends in the East” (no source is given for the quotation). The story of Ivan the Terrible features purportedly the “first information war” waged by Europe against Russia, during the Livonian war of the 16th century. And in telling the story of Soviet-era dissidents, the exhibition follows the Soviet KGB narrative that they worked for the benefit of the West in the Cold War.

After the exhibitions opened, it became clear that they featured many factual inaccuracies and even included fake quotations from historical figures. For instance, the words of the late-20th-century philosopher Arseny Gulyga were ascribed to Vladimir Soloviev, who lived about one hundred years earlier, and Bill Clinton was quoted as saying something to the effect that the U.S. had destroyed the USSR and turned it into America’s “raw material supplier”; according to the exhibition’s narrative, Clinton even used the word “samookupaemost” (the approximate meaning of samookupaemost’ is “break-even performance,” but Clinton’s alleged quote is cited only in Russian).

Secondly, it is worth noting that TV channel Dozhd’ found that the construction of the parks was funded by Gazprom, at the obvious behest of the Kremlin.

Thirdly, after the initial criticism of the parks’ poor accuracy, the organizers quietly reached out to professional historians (from the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, in particular) asking them to check all the facts and citations. This request fueled heated debate among historians: they could fix the falsified quotations, but could not change the narrative of the exhibition, and, thus, their help would only increase the power of the anti-Western and anti-liberal narrative.

Fourthly, when the Ministry of Education and Sciences recommended that schools use the exhibitions to teach history, the Free Historical Society (VIO) issued a statement about the inaccuracies and general narrative of the exhibition and received a response from Tikhon Shevkunov. In its second statement, the VIO reinforced its arguments about the quality of the materials.

Finally, I would stress the role in the creation of the parks of Metropolitan Tikhon (Shevkunov), an influential Orthodox hierarch and presumed spiritual advisor of Vladimir Putin, who is by educational background a film director. A decade ago, Shevkunov produced his own TV documentary, “Death of an Empire,” which ostensibly portrayed the collapse of the Byzantine empire while actually comparing it to the Ukrainian “Orange Revolution.” He has since acquired more resources to do the same thing: use history to defend his contemporary political ideology.

The Three Pillars on Which the Exhibition Rests are Monarchism,

Clericalism, and an All-Pervasive Conspiracy Theory

By Sergey Ivanov, Higher School of Economics (Moscow)

I have visited the “Russia: My History” exhibition in three different cities: Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Yekaterinburg. A comparison of these three “clones” shows that after numerous statements made by historians, the organizers hurried to somehow conceal the most scandalous elements of the exposition, such as the assertion that the Decembrists were British agents. The organizers also tried to deal with pseudo-quotations—that is, bloodthirsty anti-Russian statements attributed to different Western politicians—but this effort barely succeeded. Some local historians invited by the organizers to produce so-called regional components of the exhibition dedicated to local history did make attempts to improve certain aspects of the exhibitions.

|

“The pillars on which the exhibition rests have not disappeared: monarchism, rather bizarre in a country that calls itself a republic; clericalism, contrary to our constitution; and, finally, the all-pervasive conspiracy theory.”

|

However, the pillars on which the exhibition rests have not disappeared: monarchism, rather bizarre in a country that calls itself a republic; clericalism, contrary to our constitution; and, finally, the all-pervasive conspiracy theory.

Everyone is entitled to their own view of history, but this is no longer about different views since the Ministry of Education has recommended using this exhibition as a teaching aid.

In other words, the idea that all Russia’s ills come from the outside or from hostile internal forces will be hammered into schoolchildren’s heads in a centralized fashion. These internal forces are not seen just as citizens of a country who may have different ideas about how to make Russia better. They are painted as enemies who purposefully seek to create evil and whose goal is to do harm to their motherland.

With this approach to history, everything becomes incomprehensible. At the exhibition, we are told how good a ruler Nicholas I was and how wonderful his reign was—but if that is true, why did the Crimean War happen and why did Russia suffer defeat in it? If everything was so excellent under Catherine the Great, where did Pugachev’s revolt come from? And if imperial Russia was so good, what are the origins of the 1917 revolution?

|

“The idea that all Russia’s ills come from the outside or from hostile internal forces will be hammered into schoolchildren’s heads in a centralized fashion.”

|

If you accept the story offered by the organizers of the exhibition, then only a conspiracy theory can explain it all—the course of Russian history cannot be understood in any other way. Yet you must really despise your own people to claim that a huge empire with millions of people could be toppled by a few Masons.

The park “Russia: My History” does not answer any of the serious questions that our history sets before us. A simple example: in Yekaterinburg, this thoroughly monarchist exhibition is staged in a building located on Narodnaya volya Street, which is named after a terrorist, anti-monarchist organization. This street intersects on one side Decembrists Street and on the other side with a street named for the 17th-century Cossack Stepan Razin who led an uprising against the nobility and the tsarist bureaucracy. And on the final side is a circus! What is this company of tsars and regicides, if not a circus?

Deliberate Omissions

By Adrian Selin, Higher School of Economics (St. Petersburg)

The history park “Russia: My History” in St. Petersburg occupies a large space and contains four expositions. The Rurikids, the Romanovs, and the Soviet/post-Soviet period—divided in two eras, 1941–1945 and 1945–2017—are exhibited on the first floor, while the “regional component” (i.e., the history of St. Petersburg) is displayed on the third floor. The latter opened right after the New Year holidays of 2017.

After visiting the history park, a professional historian experiences a sense of personal failure. The authors of the park, however, can boast undisputed success. Drawing on uncomplicated technology (multimedia boards, projectors, and computer games and tests) and assuredly generous funding, they have reached out to the broadest possible audience. At any time, there are crowds of visitors, both individuals and groups. The implicit overlap between the park’s content and the unified standardized test (the Russian equivalent of the SAT) adds to the history park’s attraction.

The authors take a rather primitive approach that is imbued with the spirit of Eurasianism. This theory, proposed in the mid-20th century by Lev Gumilev and some other authors, focuses on Russia’s special path and is deemed deeply unprofessional by academic historians. The idea of Russia as a besieged fortress, the country’s supposed “special path,” and various conspiracy theories inform the general vision offered by the exhibition.

The historical narrative, especially of the pre-1917 period, is reminiscent of matryoshka dolls: every ruler is “encased,” as it were, in his predecessor. This is not an archaic historiography of the mid-19th century (which is broadly used by the current high school history narrative). Rather, it might best be described as post-archaic: the authors seek to supplement “political history” with a history of the everyday, but flatly reject all the professional historical knowledge accumulated since the 19th century.

|

“The authors seek to supplement ‘political history’ with a history of the everyday, but flatly reject all the professional historical knowledge accumulated since the 19th century.”

|

This approach meets visitors’ demand. The discourse of “Russia: My History” appears to be easy to perceive and to remember, based as it is on the successive reigns of tsars, princes, and general secretaries. The main chronological line of the exhibitions is a cheap version of political history informed by “which leader went where.” The presentation of each ruler is illustrated by maps showing that each leader’s contribution to the incorporation or unification of territories into Russia or to the prevention of “state collapse.” Details about these rulers that would be unprecedented even in literary fiction are provided—and indeed, most details cited in the presentation as historical appear to be fictitious.

Although factual mistakes are numerous, even more important is the cause of the inaccuracies: the facts and illustrations have been collected carelessly and hastily, apparently drawing on Wikipedia searches and without consulting with professionals. In some cases, those entrusted with creating the exhibition were underqualified and did not have proper ideas about the phenomena they were writing about. The narrative thread of “conspiracy against Russia”—and the struggle by the “forces for good” (that is, the state) against such conspiracies—runs across both exhibitions covering the pre-revolutionary period. Both the assassination of Tsar Paul I and the Decembrists movement are presented as the results of “foreign conspiracies” against Russia. The same motif is present in the portrayal of the 15th century, which includes an account of a “Teutonic spy” operating in Moscow at the time.

А few words should be said about the narrative concerning the events of the 20th century. With a few exceptions, this narrative is quite close to that of the high school version of history until it reaches the 21st century, at which point it is reduced to the pure propaganda of successes. For instance, the developments in the post-Soviet space in 2004–2016 are covered through the lens of the standoff between Russia and the West. Somewhat amusingly, “an attempt at Bolotnaya revolution in Russia” is cited among the so-called color revolutions.

|

“The developments in the post-Soviet space in 2004–2016 are covered through the lens of the standoff between Russia and the West.”

|

The creators (or, more appropriately, “consultants”) of the St. Petersburg history park’s regional component have emphasized, in private conversations, that nobody instructed them to pursue political goals. Their task, they have insisted, was simply to present the history of the region. Whether that is indeed what they have done is up to the reader to decide.

Visitors are welcomed by two mannequins, clad in the costumes of an “old Russian warrior” and a “Swedish warrior.” The mannequins stand next to a horizontal panel, a table of sorts, which shows several sets of slides, accompanied by a voiceover telling the military and political history of the Neva river delta from the 13th-century battle on the Neva between Russia and Sweden to the 18th-century Great Northern war (again between Russia and Sweden). The texts are brief, with many serious omissions that border on mistakes.

Further on, several rooms are devoted to the 18th century—probably the best part of the exhibition. A wall of “Peter’s house” (a simple wooden house built for Peter the Great in the early 18th century) is displayed. A visitor opening the door hears the tsar’s stern shout. There is a cyclorama of the Neva River and Vasilievskii Island, on which the original constructions are reproduced, as well as a worker from Tsarina Anna’s time standing in front of a furnace. The plan of mid-18th century St. Petersburg is very detailed, with many buildings marked on it. In addition, there are multimedia stands with various dates and appropriate information shown on a timeline.

While the portrayal of the 18th century provides a reasonably comprehensive picture, the 19th is presented in bits and pieces. There is a panorama of Senate Square, but not a word about the Decembrists, even though they led their revolt on that same Senate Square in 1825!

The portrayal of the 20th century is also highly fragmentary. The Whites are barely represented. The “Green” movement of 1919 and Nikolay Yudenich’s offensive against Petrograd are mentioned only in passing. The Kronstadt rebellion—a major (failed) uprising against the Bolsheviks at the end of the Civil War—is referred to simply as “the last act of violence in St. Petersburg and around,” with no indication of who rose against whom.

The part of the exhibition that has to do with the 1920s and 1930s—the extermination of “hostile classes” and the rise of Stalin’s mass terror—is beneath all criticism. It is highly reminiscent of Soviet school history textbooks, illustrated by a Young Pioneer, industrial growth, and improved living standards. There is no mention of the “philosophers’ ship” that transported intellectuals expelled from Soviet Russia, nor of mass repressions, nor of Levashovo pustosh‘, where victims of mass repressions were buried. Yet there is a mention of the opening in 1936 of the NKVD (Bolshevik Secret police) school.

The representation of the Second World War is also rather unimpressive. The 1939–40 Winter War with Finland is not mentioned at all. There is a special room devoted to the Siege of Leningrad, with a “bowl of tears” and a metronome, but hardly any information beyond that. When I asked the guide about it, she mumbled something like, “One can find plenty of information about the Siege elsewhere.”

Of the whole of the 20th century, the only section that is really well done is the one devoted to the reconstruction of Leningrad after the Second World War (in 1944–47). Yet there is nothing about the “Leningrad affair,” a series of trials of Leningrad Communist party and government officials in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Instead, what follows is a description of the “peaceful life” of the 1950s–70s, illustrated by a mannequin of an engineer with a drafting board and two others showing the wedding of a naval officer. The end of the 20th century is mostly missing: all that is presented is a wall with images showing that new construction is constantly underway, down to the planetarium, the most recently built edifice in the city.

|

“The emergence of permanent history parks in Russia can be compared to the emergence of the Institutes of National Memory that operate in a number of former Soviet and Central European states.”

|

Historians who were invited to serve as consultants were told to produce “something regional and nonpolitical.” Any given element may be not too bad, but the general impression is that of mannequins in various postures accompanied by interactive texts. Many rooms are empty except for a mannequin in a corner and an interactive board on the wall. The regional component does not amount to a comprehensive history of St. Petersburg—instead, what one sees are separate fragments.

The omissions appear to be intentional. The consultants may say that they have accomplished a large-scale and high-quality project, but the avoidance of “sensitive issues” makes the history of St. Petersburg look disconnected and piecemeal. It is simply impossible to mention the secret police school yet omit the mass repressions. And there is no word about the 1934 assassination of Sergey Kirov, used by Stalin as a pretext for the escalation of the repressions that came to be known as the Great Terror. The history of St. Petersburg cannot be limited to its construction and infrastructure.

The emergence of permanent history parks in Russia can be compared to the emergence of the Institutes of National Memory that operate in a number of former Soviet and Central European states. They are an element of the politics of history. What they seek to present is a vision of history drawing exclusively on multimedia technologies—one that does not use any real objects of the past. The vision of history they present is highly politically engaged. The organizers’ bad taste, their pursuit of maximum outreach, and their inexplicable haste has resulted, despite generous funding, in an oversimplified and primitive representation of history. The role of “regional components” is to “tie” the exhibition to the various localities where it is replicated, but also to amalgamate and, as it were, endorse the federal history.

Image credits: Ivan Kurilla