In April 2023, James Rubin, the newly appointed head of the U.S. State Department’s Global Engagement Center, visited several Western Balkan countries and warned that Russian disinformation, promulgated primarily by Serbian media platforms, had “poisoned” the region. In Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) in September, High Representative Christian Schmidt declared that there was a danger of “BiH becoming a part of the political war theatre.” Schmidt was concerned about the links between Milorad Dodik, the leader of Bosnia’s Serb entity (the so-called “Republika Srpska”), and the Kremlin. These warnings were echoed by the region’s current and former politicians. The outgoing Montenegrin President accused Russia of seeking to establish “intelligence, economic, financial, and media hubs in Serbia and the Republika Srpska” and to “incite new conflicts,” while his Croatian colleague claimed that Russian meddling had impacted the 2020 election in her country. Indeed, Russia appears keen to exploit the fragility of those Western Balkan states that remain divided decades after the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Yet I argue that Russia’s influence is far more circumscribed than these claims would suggest. First and foremost, Russia’s ability to influence events in the Western Balkans has diminished since its invasion of Ukraine. Preoccupied with the war, Moscow increasingly lacks the ability to pull the strings in this part of its “Near Abroad.” Moreover, history demonstrates that Russia has long had both a selective interest in the region and limited capacity to sway the Balkan states. The latter have typically enjoyed considerable agency and have pursued autonomous foreign policies that have often not aligned with Moscow’s.

Limited Historical Influence and Agency of Local Players

In the nineteenth century, Russia’s armies played an essential role in aiding the peoples of the Western Balkans in their struggles to regain statehood. The latter fiercely pursued independence from the Ottomans and then jealously guarded it. They courted Russia’s assistance when it suited them but did not seek to substitute servitude to one master with subjugation to another. Yet Russia, in return for its assistance, expected gratitude, obedience, and a lasting alliance. When these failed to materialize, it grew disillusioned and frustrated with the region.

Russia’s ostensible vassals in the Western Balkans had independent agendas and fought to expand their borders and power, especially around the time of the Balkan Wars (1912-1913). These plans were sometimes contrary to Russia’s interests and risked pulling it into costly wars. St. Petersburg’s policy toward the Western Balkan region was largely dictated by its relations with the other great European powers of the day, whose support was required for territorial changes in the Balkans in order not to upset the delicate balance of power between Europe’s big players. This was particularly visible following Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1856), which revealed its weakness and propelled Tsar Alexander II (1855-1881) and his foreign minister, Alexander Gorchakov, to undertake domestic reforms while pursuing a less adventurous foreign policy. The trend of Russia (and later the USSR) attempting to restrain its nominal vassals persisted into the early Cold War period. In 1947-1948, the Soviet Union found itself frustrated with its inability to rein in Tito’s Yugoslavia. The latter pursued an ambitious expansionist agenda toward neighboring Albania and risked (in Moscow’s eyes) inviting a Western intervention. Indeed, as studies show, this episode precipitated the famous split between these two communist allies.

Russia’s Recent Balkan Policy

Following the end of the Cold War, Russia’s policy continued to be guided by relations with the West, the positive development of which was Moscow’s priority in the 1990s. As one scholar has pointed out, President Yeltsin followed the Western lead in accepting and implementing the Dayton Accords (despite the Bosnian Serbs’ discontent with the treaty), and even Putin was prepared to make a deal with the West on Kosovo under certain conditions, although this eventually fell through.

Russia’s overall policy in the Western Balkans before Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine in 2022, did not offer solutions to existing disputes. Instead, Moscow primarily sought to ensure that its opinions would continue to matter (and that it would have clients in need of the Russian veto power at the UN Security Council). As Maxim Samorukov notes, Russia’s continuous attention to the Western Balkans is driven by a fear that the West (in cooperation with local actors) might opt to solve lingering unresolved political issues regarding Bosnia and Kosovo and eliminate Russia from the region. Indeed, as I have previously argued, status concerns (being recognized by the West as a “great power”) have been one of the main motivations for Russia’s activity in the Western Balkans. As part of its status-seeking goals, Moscow moved from cooperative tactics and working with the Western security guarantors in the former Yugoslavia during the mid-1990s to more confrontational competition and attempts to undermine regional states’ accession to NATO through coup attempts (as in Montenegro in 2016) or outright destabilizing acts (such as refusal to recognize the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina). The Western Balkans have thus transformed into another arena in which for Russia to pursue larger practical objectives.

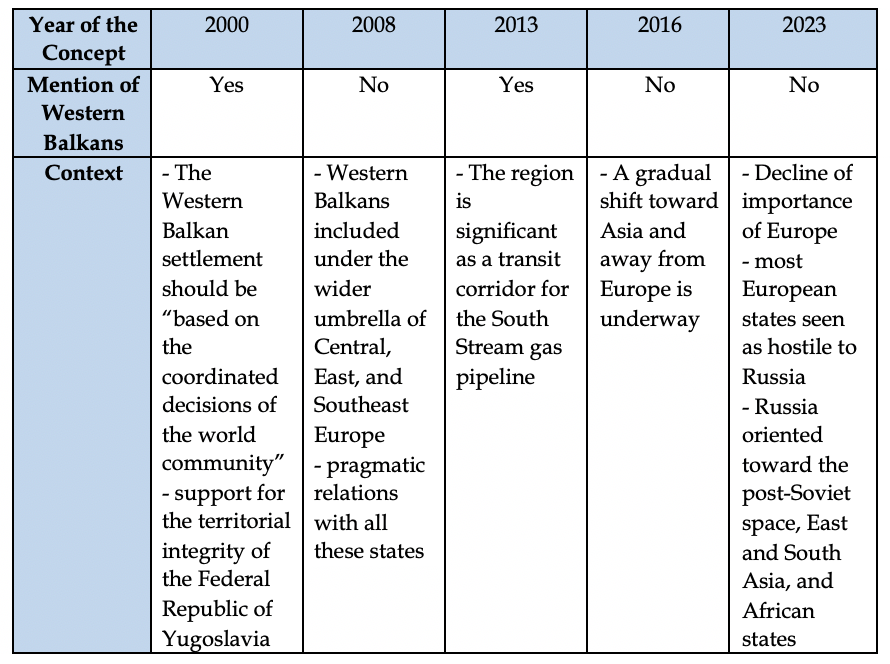

The reality is that Moscow has rarely prioritized the Western Balkans in its foreign policy. Instead, it has compartmentalized this region to serve a specific purpose in its foreign policy and relations with the West. In the wake of its invasion of Ukraine, the region is even less likely to be of vital importance. Russia’s Foreign Policy Concepts of the past two decades (see Table 1) have only mentioned the Western Balkans on two occasions. In 2000, when Putin came to power (a year after the 1999 Kosovo war), the Concept stated that “Russia [would] give all-out assistance to the attainment of a just settlement of the situation in the Balkans.” It would also strive to “preserve the territorial integrity of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and to oppose the partition of this State.” In 2008, when Kosovo declared independence, the Western Balkans were not specifically mentioned in Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept. Instead, they were included in the category of “Central, Eastern, and South-Eastern Europe,” with which Russia was “open to further expansion of pragmatic and mutually respectful cooperation” provided these states’ genuine readiness for it.

Table 1. The Western Balkans in Russia’s Foreign Policy Concepts, 2000-2023

The 2013 Concept mentions the Western Balkans in a purely pragmatic context: it was to be the transit route for Russia’s “South Stream” gas pipeline, which aimed to reach the far more critical Western buyers. Hence, Moscow aimed “to develop comprehensive pragmatic and equitable cooperation with Southeast European countries.” After this project was scrapped in late 2013, the 2016 Concept reverted to not mentioning the Balkans. The most recent iteration (from March 2023) goes even further. The Western Balkans are not mentioned at all, even if they are presumably included in broader relations with European nations. They are deprioritized and described as hostile toward Russia.

Sources of Instability

While deprioritizing the region, Russia maintains the will and possesses inexpensive tools to undermine the West’s regional objectives—namely the Western Balkans’ gradual integration into the Euro-Atlantic institutions. An April 2023 report by the European Parliament notes that Russia has used “targeted and low-cost (asymmetric) operations in the information space, including (dis)information campaigns, cyber-attacks, and clandestine operations, combined with the support of proxy organizations and the use of political and economic influence.” The report also suggests that these tactics have produced results by seizing on pre-existing conflicts and cleavages within all six Western Balkan countries. Especially in Serbia, the public sphere has been, in one scholar’s words, dominated by a rampant 1990s-style anti-Western nationalism. In contrast, Russia is treated mostly favorably by local media. Even the ongoing illegal invasion of Ukraine is frequently presented as a conflict between Russia and the West; early on, the widely read pro-government Serbian tabloids even accused Ukraine of attacking Russia.

While these wild accusations against Kyiv have subsided, an anti-Western spin on the origins and causes of the conflict persists. Moreover, Russian media such as Sputnik News and Russia Today have launched Serbian-language websites to reach local audiences. Hence, it comes as little surprise that, as a recent study by Ivanov and Laruelle shows, over half of Serbs want their country to remain neutral in this conflict, 54 percent consider Russia to be their country’s most reliable foreign partner, 35 percent think Serbia should support Russia (only four percent are in favor of supporting Ukraine), and nearly 78 percent oppose Serbia joining in imposing sanctions against Russia. Unsurprisingly, the government in Belgrade has frequently played the “Russia card,” whether posing as Russia’s last friend or threatening the West with its citizens’ Russophilia, and pro-Russian gatherings have been organized by far-right groups.

For all this, the Western Balkan front has mostly remained “quiet.” While tensions between Serbia and Kosovo, in particular, have continued, there have been no new conflicts, a fact that hints at Russia’s limited sway.

Invasion of Ukraine and Russia’s Prospects in the Balkans

Given Russia’s preoccupation with the war, it has struggled to maintain leadership even in what former President Medvedev proclaimed in 2008 to be its “regions of privileged interests.” The invasion of Ukraine has diverted some of Russia’s attention and resources from its “backyard.” The intermittent clashes between Moscow’s Commonwealth of Independent States allies Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have been embarrassing, and the more public collapse of Russia’s relations with its “client” Armenia came as a surprise. This led scholars to speculate that Russia’s primacy in the region was nearing its end and that its bold claim to a sphere of “privileged interests” was untenable.

Therefore, save for a few ostensible “pro-Russian oases”—namely Serbia and Bosnia’s Serb entity, Republika Srpska—that frequently play the “Russia card” for domestic purposes, the region’s pragmatic players do not consider Moscow a real option. They have either joined Euro-Atlantic clubs in the past few years or are deep in discussions to become members of the European Union. Montenegro, which scholars like Bechev describe as perhaps the part of the former Yugoslavia with the most deeply rooted pro-Russian sentiments, exemplifies Russia’s limited sway over the region’s states. Russia was among the first states to recognize Montenegro’s independence in 2006 and gradually became a leading investor in the country’s tourism sector. However, it could not prevent Podgorica’s political elites’ turn to Western institutions, and in particular NATO, of which Montenegro became a member in 2017.

While Moscow attempted to disrupt this first by seeking unrealistic rights to use a naval base on the Montenegrin coast, then by plotting to remove the elected government, and later by backing protests organized by the Russia-friendly Serbian Orthodox Church, it made no major course correction, even following significant political changes in Montenegro in Fall 2020. The present government, composed chiefly of Russia-sympathetic parties and heavily influenced by the Serbian Orthodox Church, followed the West in imposing sanctions on Russia and expelled nearly all Russian diplomats in Fall 2022. The recent parliamentary election—while not yielding a clear winner or a stable government—saw the majority of votes go to declaratively pro-EU parties and coalitions.

Finally, while Serbia is ostensibly a firm Russian “friend,” its loyalty is hardly guaranteed. As Maxim Samorukov writes, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić has never been a genuine Russophile. Instead, he deploys Russophilia instrumentally, engaging in the classic courting of Russia that was common among Balkan leaders in an earlier age. In 2021, he claimed that relations were at their “highest level in history” and stated that Serbia considered itself “privileged” to be Russia’s strategic partner. He has admitted to being “proud of having very good relations” with Russia, even as others have sought to hide this. He opened his recent UN General Assembly address by claiming that he represents a country on the path to joining the European Union but also unwilling to “step on traditional friendships it ha[s] built over the centuries.” Rather than imposing sanctions like the rest of Europe, Serbia has continued to engage with Russia, securing an extension of affordable gas supplies.

Yet while the government in Belgrade continues to perform something of a balancing act, its room for maneuver is shrinking. While Vučić unsurprisingly made the Kosovo issue and lecturing the West about its double standards the centerpiece of his UN address, he also reaffirmed that his country supported Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty (it voted in favor of the UN General Assembly resolutions in 2022). Similarly, while the Serbian leader claimed he would resist imposing sanctions on Russia for as long as possible, Belgrade hopes its relations with Russia will be “cut indirectly, as an inevitable by-product of the EU’s actions,” thereby enabling Vučić to avoid taking the blame. His government realizes that Serbia’s—and the region’s—future lies with Europe, and particularly the European Union, which is the source of 70 percent of investments in the country.

Most importantly, if Russia ever presented a viable alternative to the European Union for the Western Balkan states, this is hardly the case in 2023. In its latest Foreign Policy Concept, Moscow has made it clear where its priorities lie: relations with the “Near Abroad,” China and India, the Asia-Pacific region, the Islamic world, the African continent, and Latin America and the Caribbean supersede ties with Europe and the “Anglo-Saxon world.” Moscow will not wholly abandon the Western Balkans, but it stipulates that the establishment of a new coexistence requires “creating conditions for the cessation of unfriendly actions by European states and their associations” and “a complete rejection of the anti-Russian course.” Yet given that over the past decade or more, when it had more will and means to interact with the region, Moscow focused primarily on catching the West’s attention by acting as a spoiler rather than on proposing real solutions to concrete issues, Russia is even less likely to be a constructive partner during and after the war in Ukraine. This should motivate the remaining unaligned EU hopefuls in the Western Balkans to speed up domestic reforms in hopes of improving their prospects of attaining membership soon.

Janko Šćepanović is Assistant Professor of International Politics at the Shanghai Academy of Global Governance and Area Studies (SAGGAS), People’s Republic of China.