(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Poland will hold general elections on October 13, 2019. Recent exit polls suggest that the ruling right-wing, conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party will maintain its dominant position. A key aspect to unravel is the indirect impact of Russia on the Polish political milieu in this year’s European (May) and national (October) elections. This is particularly significant because the PiS party has extensively instrumentalized Russia-linked factors in its narrative battles. The party’s primary political opponents are the Civic Coalition (KE) electoral alliance and Donald Tusk himself, the founder of the Civic Platform (PO) party and the current president of the European Council.

For this brief examination, clusters of PiS policy positions were grouped under a “Russian threat” theme. From this context, discourses in PiS campaigns about the “Smolensk tragedy”—the 2010 plane crash that killed 96 members of the Polish government including President Lech Kaczynski—stand as the prime case study of efforts to discredit and delegitimize the liberal part of the Polish elite through political manipulations of an emotional, unsettled, national chronicle that may or may not involve Russia. For his part, Tusk has accused PiS of having pro-Kremlin positions and of pursuing illiberal policies that could lead to a “Polexit” from the European Union, potentially triggering the EU’s further disintegration. In these charged political races, Russian factors have emerged as both opportunities and challenges for political actors amid a storm of accusatory narratives about governance, corruption, and allegiances. Even though Polish citizens are generally Russia-skeptical, there are sufficient anti-Western feelings and conservative and religious value systems for Russia, an established, symbolic bogeyman for Poles, to find soft spots through which to influence both domestic and European politics.

Polish 2019 National and European Elections

In the upcoming national election on October 13, PiS is expected to receive about 46 percent of the vote versus 30 percent for KE. Earlier this year, PiS strengthened its presence in the European Parliament’s European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) as a result of the European Parliamentary elections on May 23-26. PiS now is represented by 26 members of the European Parliament (MEPs) with a 27th-in-waiting (until Brexit), having garnered 45 percent (6.2 million) of the votes in a demonstration of the highest public support for a political party in Poland since it began to participate in European Parliamentary elections. KE received 38 percent, or 22 MEPs, with about 5.2 million votes. The Spring (Wiosna) party, Robert Biedroń’s social-democratic pro-LGBT group that was founded shortly before the elections in February 2019, received 6 percent of the vote (827,000) and 3 MEPs. In August, the previously fragmented opposition, which included KE, PO, Spring, Modern (Nowoczesna), Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), Together (Razem), and a coalition led by the Polish People’s Party (PSL), decided to join forces to nominate candidates for the Senate in the upcoming parliamentary elections. This recent agreement was meant to prevent PiS from taking control of the upper chamber of parliament.

Meanwhile, there is mounting speculation in the Polish media that Tusk is likely to run in next year’s presidential election (August 2020), which further fuels already-intense domestic political debates. In this contested political space, Russia has naturally emerged as a symbolic bogeyman, opportunistically used by Polish politicians to accuse each other of all sorts of corruption and bad intentions related to the EU. The heightened degree of political polarization in Poland first became evident in March 2017 when Tusk received overwhelming support during his re-election for president of the European Council but embarrassingly failed to safeguard votes from the Polish state delegation. Returning to Warsaw, then-Prime Minister Beata Szydło was feted to a hero’s reception for the votes against Tusk.

Russia as a Political Hot Potato in PiS’ Political Debates

Even though, ostensibly, there are no major differences between the PiS and the liberal opposition with regard to their overall position vis-à-vis Russia, each accuses the other of having purported links to the Russian government to advance its political agenda, as can be gleaned in statements made by the twin brother of the late Polish president, Jarosław Kaczynski, and Radosław Sikorski, a key opposition figure who previously served as the minister of foreign affairs. Thus, Russia, despite apparently being only in the background of the tragedy, is used by political forces to try to score easy points against each other.

The formation of the 73-member Identity and Democracy (ID) faction in the European Parliament in June 2019, spearheaded by Italy’s former deputy prime minister and leader of the Lega Nord party, Matteo Salvini, represents an excellent demonstration of the crucial importance attached to the Russian factor in Polish foreign policy. Salvini’s initial idea to create the largest right-wing European coalition–supported by France’s National Rally, Germany’s AfD, Austria’s FPÖ, the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE), and a number of others–was ignored by Hungary’s right-wing ruling Fidesz party and Poland’s PiS. In the case of the latter, the pro-Russian foreign policy orientation of National Rally, Lega Nord, and AfD played a decisive role in its rejection of Salvini’s overtures, as according to PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński to Polish radio.

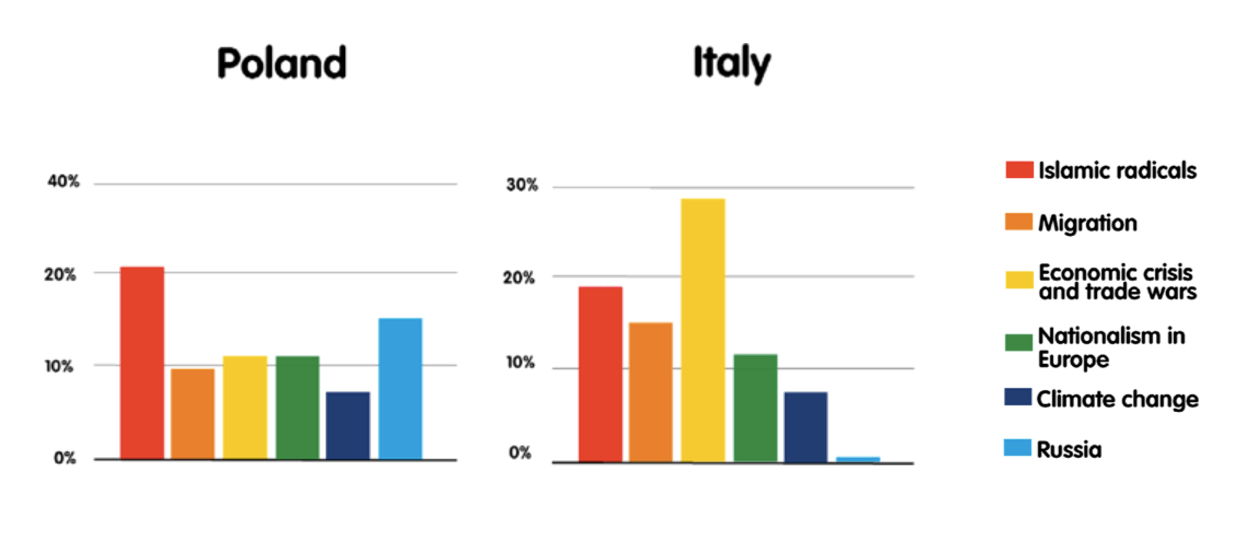

Indeed, as an April 2019 ECFR report shows, Poland and Italy perceive Russia very differently: if Poles rank Russia as the second highest threat facing Europe after Islamic radicalization, Italians, along with Germans, Hungarians, and the French, place Russian threats at the bottom of their list (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Single Biggest Threat for Europe Today

Source: ECFR, April 2019

Yet, in Poland’s heated, domestic, political debates (for years), the opposition and liberal forces have been paradoxically accusing PiS of pursuing the Kremlin’s interests. On occasion, these accusations have been grotesque and even insulting, as when columnist Jacek Żakowski from the liberal newspaper Wyborcza suggested that the acronym PiS stands for “Putin i Samodzierżawie” or “Putin and Autocracy” rather than “Prawo i Sprawiedliwość” or “Law and Justice.” Żakowski justifies this by pointing out that PiS shares the Russian government’s Euroscepticism and social conservatism as well as its disdain for the rule of law and diversity. “It is not surprising that PiS speaks so loudly about reparations from Germany, and is silent about reparations from Russia,” he said.

Russian-Polish relations in the energy sector–in particular Poland’s importation of 333,132 tons of coal extracted from Ukraine’s separatist-controlled Donbas region from March 2017 to December 2018, as reported by the Polish media in June–raises another set of uncomfortable questions for PiS. At a meeting at the University of Warsaw in May, Tusk commented on this, noting that it represents “an extremely strange patriotism by PiS when importing Russian coal from Donbas and indirectly financing President Putin’s imperial ideas.” In his earlier interviews, he accused PiS of indirectly supporting Putin’s interests because of their aligned Euroscepticism, calling PiS members, “‘contemporary Bolsheviks’ who threaten the country’s independence.”

The restoration of Russia’s voting rights at the Council of Europe this past summer significantly increased the domestic criticism of PiS. Former president and co-founder of the Solidarity movement Lech Wałęsa, in a tweet (@PresidentWalesa) on July 3, blamed PiS for this development (without providing any evidence). Nonetheless, the Polish government was put on the defensive to such an extent that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had to issue a special press release publicly rebutting speculation that it had “voted” for Russia.

The Weaponization of the “Smolensk tragedy”

The Smolensk airplane crash tragedy in April 2010 that killed almost one hundred members of the Polish government and the president has long been weaponized in Polish political debates. The fact that this tragic trip to Russia was to commemorate the execution of 22,000 Polish soldiers and intellectuals by Stalin’s secret police in 1940 in Katyn brought to the forefront debates not only about national memory but also on what constitutes “real patriotism” and “Polishness.” In the words of professor Zbigniew Mikolejko at the University of Warsaw, the deceased president’s brother constructed a “religion of Smolensk” phenomenon grounded in his personal family trauma that resulted in Polish society finding itself deeply and bitterly divided. One part of society shared the mourning rituals for those who perished in the crash, blending Catholic liturgies, pagan torchlit marches, and civic meetings with a proliferation of conspiracy theories about the catastrophe. On the opposite end, sceptics rejected and criticized those rituals, suggesting that they were demonstrations of political loyalty to PiS rather than expressions of national unity.

The PiS leadership considers Tusk, who served as prime minister over 2007-14, the key person responsible for the plane tragedy, which is seen not as a tragic accident but as his conspiracy with the Russian government. Warsaw officials have been persistently developing this narrative, which explains the plane crash as a result of an explosion on board despite failing to provide supporting evidence, as pointed out repeatedly by the liberal opposition. And yet the highest level of PiS representatives, including Andrzej Zybertowicz (advisor to President Andrzej Duda), Ryszard Czarnecki (former vice-president of the European Parliament), and Antoni Macierewicz (defense minister), openly claim that the Smolensk tragedy is an object of external political machinations in which Russia plays a decisive role.

Figure 2. A Pro-PiS Party Tent on the Commemorative Day of the Smolensk Tragedy (Warsaw, April 10, 2019)

One of the posters depicts President Putin and then-Prime Minister Tusk under the headline “[They] Succeeded!” (Source: author)

Conclusion: The Polish-Russian “Game of Tag”

Some critical voices outside of Poland’s political establishment maintain that frequent mentions of Russia in domestic debates are not unfounded. As a detailed investigative report issued in August 2016 by the Hungarian think-tank Political Capital Institute (PCI) shows, the Russian government has been trying to reach Polish audiences to spread reactionary, anti-immigrant, anti-Ukraine, and generally anti-EU sentiments. These aim to undermine Poland’s foreign policy and distance it from liberal values and institutions. For additional details, see the chart titled “Figure 2. Direct and indirect ideological influence of the Kremlin in Polish organizational networks” on page 54 in the PCI report. Due to historical issues with the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, Poles are still strongly Russia-skeptical, but there are enough conservative, religious, and anti-Western feelings that could make voters vulnerable to Russian propaganda.

The supporters of the nationalist parties, both far left and extreme right, are indeed among the potential (pro)Russian audiences. Seen from this position, even the Smolensk conspiracy theories, which have mostly originated from Poland, can be viewed as compatible with Russian efforts. According to what Edward Lucas and Peter Pomeranzev wrote in a 2016 CEPA report, they:

“…promote extreme Polish nationalism—even anti-Russian nationalism—with the goal of making Poland look unreliable and hysterical to its Western allies. It is important to note that official Russian policy—for example Russia’s refusal to return the wreckage of the plane to Poland—has helped to feed speculation over the Smolensk disaster.”

Paradoxically, by reaching for a consensus on Poland’s foreign policy toward Russia, the main political rivals (KE and Tusk) take reputational risks by engaging in discursive games about the “Russian threat.” The question of what the final prize is in this “game of tag” remains unanswered. What is clear is that while the Kremlin has insufficient direct power over Polish politics, its soft power machinations in Poland are deep and draw at particular, fertile, historical and contemporary social attitudes—to the benefit and detriment of both the progressive and conservative sides.

Alexandra Yatsyk is a Coordinator of the Baltic-Black Sea Region Project at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

[PDF]

Homnepage image credit: author