A massive national reconstruction effort for Ukraine, guided by that country’s government and popular will, must be launched even before Russian aggression is defeated. At this writing, with large-scale hostilities and widespread Russian attacks against civilians still underway, it might seem premature to begin thinking about the future course of Ukraine’s re-development. But this is precisely the time when such thought needs to be given and initial steps taken in program and logistical planning so that rehabilitation can commence when the required capital is in hand from European, U.S., Canadian, and other governments, international organizations, private business investments, and reparations from Russia. Reconstruction that will require vast sums should consider prior regional geo-economic tendencies, such as a westward realignment, and not the outdated notion of an agrarian west and industrialized east when selecting and rebuilding key civilian facilities.

Regional Recovery

The reconstruction plan should be seen as two-track. First, when peace is restored, rebuilding human security infrastructures such as hospitals and schools must be a high priority. Once areas are cleared of unexploded ordnance and de-mined, special attention must be paid to places where Russian forces have wrought severe damage through indiscriminate shelling and bombing of urban areas, a practice that has been characteristic of the Russian military in every conflict in which they have been involved since the 1990s. As a consequence, vast numbers of apartments and homes have been destroyed or rendered uninhabitable. These needs are pressing not only for those still living in heavily damaged zones but also to attract and accommodate returning refugees and internally displaced persons. Likewise, repairing economic infrastructures such as transportation lines and physical plant is vital to any restoration effort. As Cynthia Buckley and we described in an earlier PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, when Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014, it wrought heavy damage to civilian facilities in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk (the Donbas). The devastation now is far more expansive and extensive.

Secondly, when it comes to restoring the Ukrainian economy, it is important to understand that there is a strong spatial aspect to how economies in general function, and Ukraine is no exception. In that context, we suggest that it is important to understand the regional pattern of economic growth (and decline) that manifested in Ukraine prior to and after Russia’s invasion in 2014. The Ukrainian economy—like most others—experiences cycles wherein some regions have prospered while others have declined. These geographic trends do not occur randomly but rather happen on account of underlying spatial, social, and economic factors that can favor some areas over others for investment and growth during any given period. Assuming that government and private economic development capital will at some point be finite, it becomes crucial to prioritize where precious investment monies are directed to optimize limited resources.

The Past Might Be Prologue

There are many facets of the geographic, economic, and societal conditions that interact to shape the manner in which development occurs over space and time. Dating back to foundational works on regional economic inequalities by Gunnar Myrdal, Jeffrey Williamson, and I. S. Koropeckyj, and including more recent scholarship, it is reasonably well understood that within countries, regions ebb and flow according to changes in internal and external factors of production and consumption of various goods and services. Briefly, the spatial concentration of factors of production (agglomeration) at a given period typically leads to interregional inequalities, but those inequalities might then be mitigated, at least to some extent, as subsequent diseconomies of scale and changes in the composition of production create new possibilities for previously lagging regions.

Not unlike other large and diverse countries, Ukraine also manifests significant internal spatial variability in economic productivity, and these regional patterns have predictably changed over the years as the determinants of growth have shifted. The OECD documented and analyzed spatial trends in social and economic development in Ukraine and found that in 2014, despite having a relatively low index of regional gross domestic product (GDP) concentration compared to other OECD countries, economic growth had been much more geographically concentrated. But the specific regions that rose or fell in the years prior to the onset of war in 2014 had already begun to change significantly. According to the OECD, before 2010, regions (oblasts) in eastern Ukraine with economies based largely on mining, metallurgy, and machine building, and also the city of Kyiv (as the country’s national capital and dominant urban financial and services centroid), were among the most prominent contributors to national GDP and the destination of most foreign direct investment (FDI). Indeed, the Donbas accounted for 14.4 percent of GDP. But after that year, these previously more productive regions, with the exception of Kyiv, began a long-term decline relative to regions in the center and western parts of the country that were becoming relatively more productive.

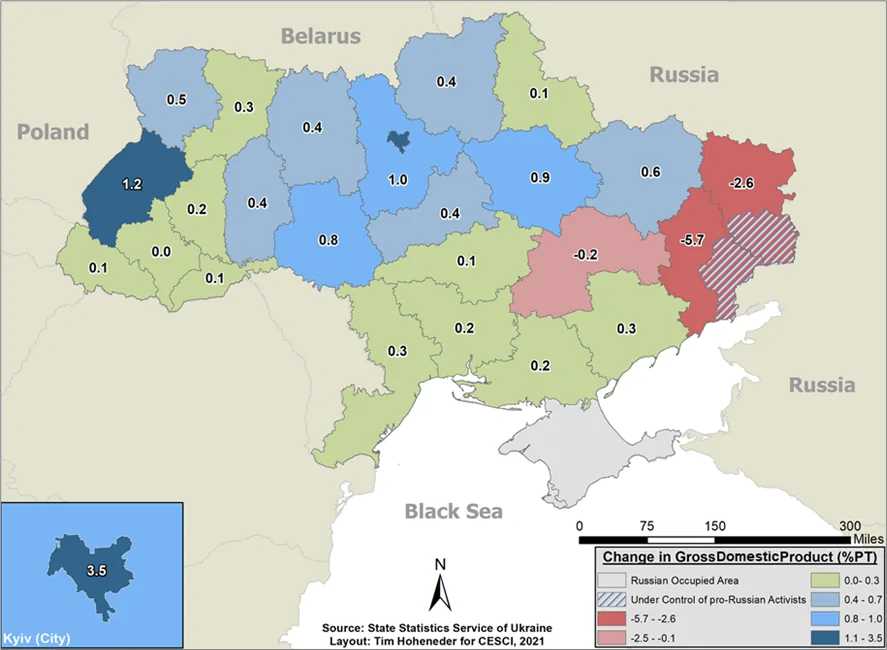

In order to track regional variability within the Ukrainian national economy, we used data on the shares of Ukrainian GDP for 2013 by region as a baseline and compared those with 2019, the most recent figures available. As Figure 1 illustrates, the Ukrainian economy was realigning geographically much more to the central and western regions and the city of Kyiv, with Kharkiv being the one eastern region that continued to show significant growth. Most noteworthy and not surprising given the Russian invasion in 2014, the major decline is in the Donbas. However, it is important here to note again that the economic decay in the Donbas was already well underway from 1999 to 2013, mainly owing to its older mining and industrial base and shifts in export trade relationships.

Figure 1. Changes in Share of GDP by Ukrainian Region (2013-2019)

The realignment of foreign trade away from Russia and toward Europe and China favors the more rapidly expanding regions post-2010. In terms of the increase in their share of national GDP, the top five growth regions comprise, in descending order: Kyiv City, Lviv, Kyiv, Poltava, Vinnytsya, and Kharkiv regions. Some particular examples stand out, but it is not always readily apparent how much of the change is unique to the given regions and how much can be generalized into a broader trend. For example, the Kharkiv region narrowly escaped the fate of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in 2014, the former having been secured by swift anti-separatist action and the political adroitness of Kharkiv city’s then-mayor Hennadiy Kernes. It has not been as fortunate in the new wave of Russian aggression.

Kharkiv, post-2014, illustrates how Ukraine’s economy has changed. Despite having had its extensive cross-border commercial ties with Russia greatly reduced, the city and its environs adapted by focusing on production for the Ukrainian military and increasing exports to new markets. Similarly, the experience of the Lviv region is instructive, as its information technology sector has experienced rapid growth, illustrating the non-industrial track to higher levels of development, especially when fueled by FDI. The old stereotype of the industrialized east and agrarian west is long outdated.

Human Capital is Needed

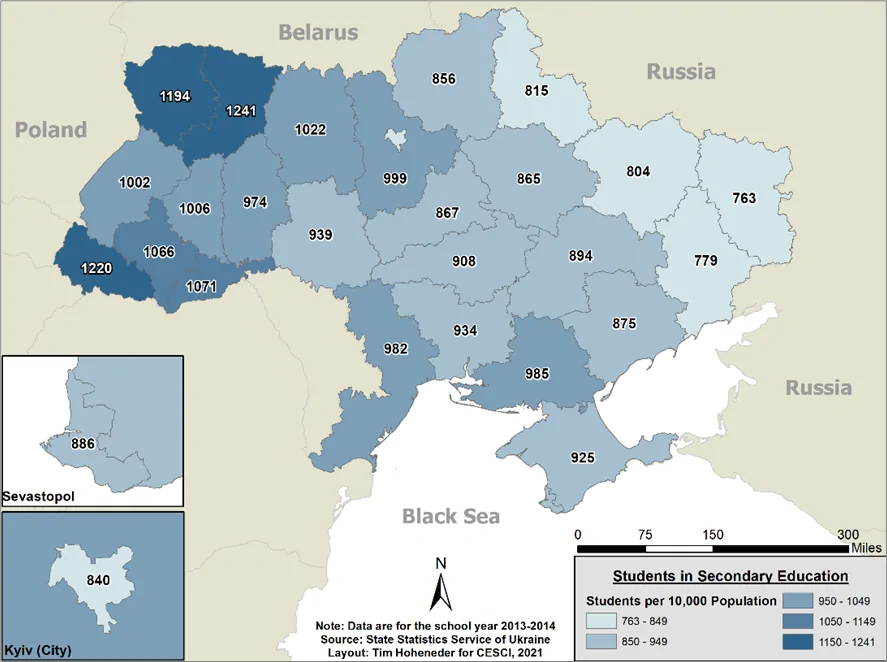

As economies increasingly decouple from extractive industries and move more toward skilled and export-oriented manufacturing, demand for a better educated, civic engaged, and healthier workforce grows commensurately. This has been shown to be especially important in determining the regional economic potential in Ukraine. We find major differences in human capital across Ukraine’s regions. As Figure 2 shows, in the last pre-war year (2013), regions in the western part of Ukraine were performing better in education, a vital component of a skilled workforce.

Figure 2. Students in Secondary Education per 100,000 by Ukrainian Region (2013)

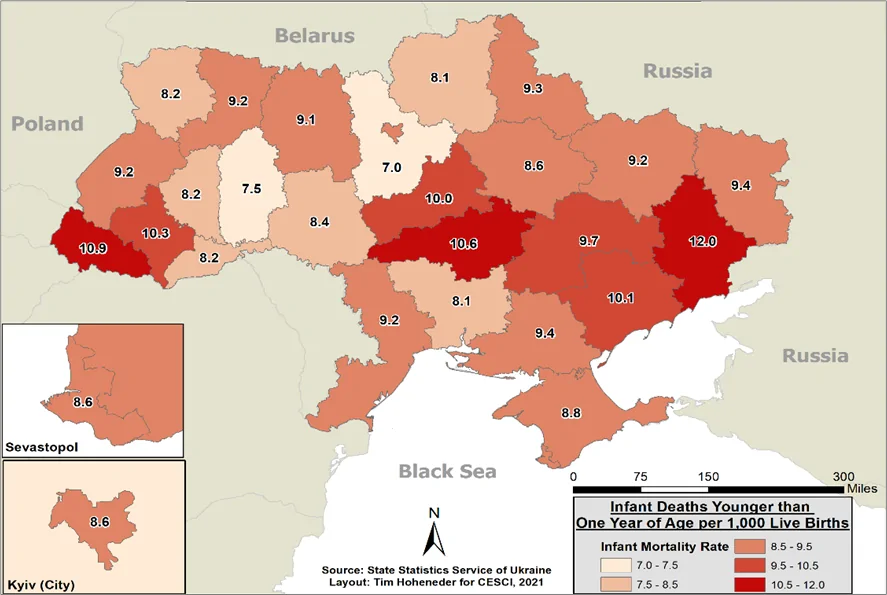

Also, the health and well-being of the population across regions is an important aspect of human capital and labor force quality. In this regard, a key measure is the infant mortality rate, which is universally viewed as an important part of human security. Here again, data from 2010 show, in Figure 3, that before the outbreak of war in 2014, with some exceptions, regions west of the Dnipro River tended to have lower infant mortality and those in the more heavily industrialized regions in the east, higher rates. Note in particular that Donetsk region had the highest rate of infant deaths in the country.

Figure 3. Infant Mortality Rate by Ukrainain Region (2010)

Consequences and Conclusions

To date, the worst destruction wrought so far by the Russian armed forces has been in the Kyiv and Chernihiv regions in the northeast of Ukraine, along an arc stretching eastward through Sumy, Poltava, and Kharkiv regions and thence through the Donbas, and finally westward along the Black Sea coast, with the city of Mariupol all but leveled. As we showed in Figure 1, the Chernihiv, Poltava, and Kharkiv regions had been in the higher positive regional growth category; thus, the destruction in these areas has a disproportionate impact on the national economy, as does the damage being incurred in Kyiv and its region. On the other hand, the central and western regions where the fighting has not been as intense will, despite some attacks on key industrial facilities, be better positioned for recovery.

The toll being paid by the Ukrainian population is unspeakably horrific. Given their sacrifices, it is all the more important for post-war reconstruction efforts to proceed according to their priorities. But, the international community can begin planning for these efforts by paying close attention to how Ukraine had already been reorienting itself antebellum. Once the human security infrastructure has been repaired, capital investment to rebuild the country’s economy might be better directed initially to areas in the center and western parts of the country that are best positioned to receive it and have recently been the focal point of Ukrainian-led economic development. Economic infrastructure in these regions will be in much better condition to accommodate production by virtue of their greater distance from the heaviest fighting and thus more secure against any future Russian threat. As Ukraine’s recovery proceeds, growth will return to the most severely damaged areas, but their role in Ukraine’s overall economic landscape may change. Indeed, several dozen firms have already re-located away from the immediate battle zone.

Together with the Ukrainian government and research and development agencies there and abroad, engaging in the needed analysis required to guide Ukraine’s recovery ought to be a priority now. Ukrainian decisions on regional economic development prior to Putin’s escalation of the war show a pathway to post-war reconstruction. Recovery, if properly conceived and executed, will hasten the post-war renaissance and facilitate the new Ukraine that will emerge.

Ralph Clem is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Senior Fellow at the Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University.

Erik Herron is the Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of Political Science at West Virginia University.