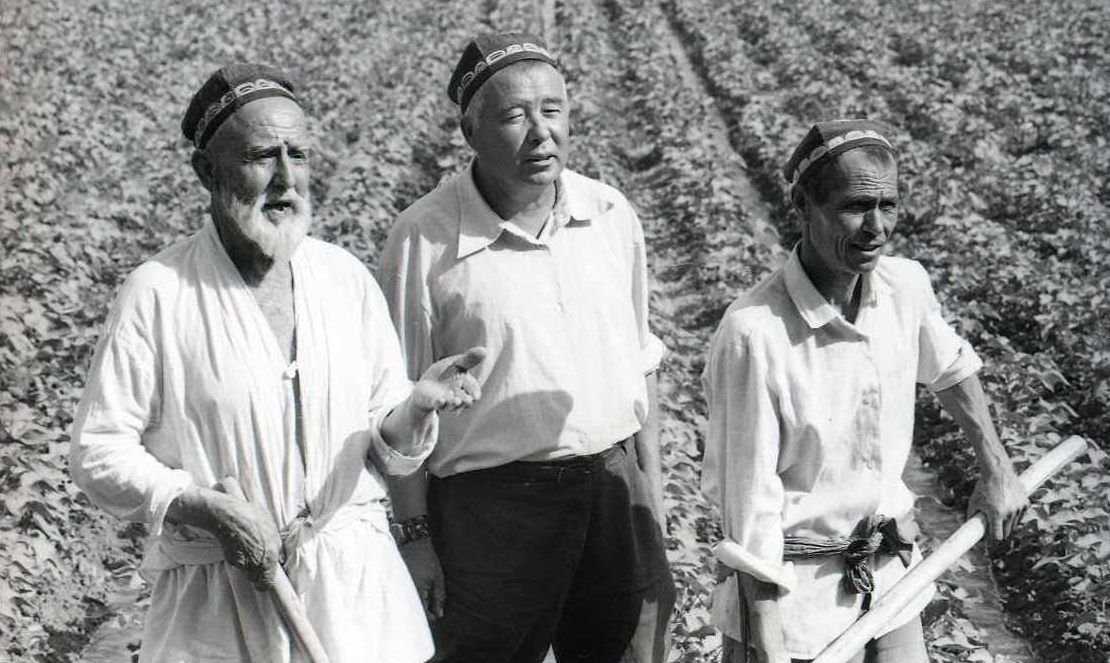

Tajik cotton farmers (credit).

► Based on both archival work and oral history, the growing research on the 1960-80s development policies in the Soviet periphery offers a more nuanced picture of how the Communist regime managed its population’s expectations and needs.

Maria Lipman: In your book, you look at modernization—or industrialization—in Central Asia, specifically Tajikistan. You focus on the period after Stalin’s death. Why did you pick that period?

Artemy Kalinovsky: There are several things that happened both internationally and in the Soviet Union that make that era particularly interesting. One is, of course, that de-Stalinization opened up political and intellectual space; this included relative freedom to talk about history and the state of economic development. A second is that under Nikita Khrushchev the Soviet Union tried to become heavily involved in the whole process of decolonization, much more so than under Stalin. That led the Soviet government to pay more attention to its own peripheries, such as Central Asia and the Caucasus. Focusing on this period gave me an opportunity to juxtapose this story—which has been largely ignored by scholars—with the better-known story of Western development aid.

|

“Looking at the Soviet Union ‘from Tajikistan’ enabled me to look beyond Central Asia in order to understand how the Soviet system functioned. I was interested in how it worked in the post-Stalin period, when it no longer relied on terror.”

|

Besides, looking at the Soviet Union “from Tajikistan” enabled me to look beyond Central Asia in order to understand how the Soviet system functioned. I was interested in how it worked in the post-Stalin period, when it no longer relied on terror. How did the party and state conduct mass mobilization and build something like the Nurek Dam, which required massive resources and gigantic human effort? What kind of commitments did the Soviet government need to make to the people? What kind of things did people expect of, and demand from the political and welfare authorities, as well as construction organizations?

At the same time, one has to take into account the legacy of the Stalin era. What was left after Stalin was gone? Everybody who has worked on post-Soviet history—anywhere in the former Soviet Union, but particularly, I think, in Central Asia—has come across this phenomenon of nostalgia for the 1960s and 1970s as a period of relative prosperity, peace, even freedom, and a reluctance to talk about any kind of resistance to Soviet projects and Soviet rule. And yet, of course, the 1960s, and especially the late 1950s, were only a few years away from Stalinism and the terror and fear of that time.

Crowds in Tajikistan react to the break up of the USSR (credit).

Lipman: You compare the modernization/industrialization strategies pursued by the “First World”—that is, the United States—with the “Second World,” and you also compare concrete projects: the Nurek Dam the Soviet Union built in Tajikistan, water-management activities by the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the dam built by the Americans in Afghanistan. Were there more similarities than you had expected to find?

Kalinovsky: There were definitely more similarities than I expected, but, in retrospect, I probably should have been more aware that I would come across these similarities. The ideas about how to get from an agricultural society to a “better” industrial society had been circulating between the socialist and capitalist worlds since the first half of the 20th century. For instance, historians who have done work on the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) have noted that some inspiration was drawn from the early Bolshevik experiments with big dam projects in the 1920s, and, of course, it is not just the Bolsheviks who were doing this. The Americans thought that they had achieved something really miraculous with the TVA, so when they undertook development projects abroad in the post-World War II period, one can find a “TVA” in Afghanistan, another “TVA” in Vietnam, and so on.

What was different about what the Soviets were doing in the 1950s, compared to the Americans at the same time, was that the Soviets had realized how disastrous a lot of what happened under Stalin was. In the same river valley where the Nurek Dam was built, there had been another project in the 1930s that involved forced labor. That construction collapsed and was washed away, and many of those involved in the project ended up in prison camps, including the person who later re-emerged as the chief engineer of Nurek. In the 1960s, the Soviets were working much more carefully, much more slowly, and would rather miss deadlines than rush ahead—what they initially promised to build in five years eventually took twenty.

The Nurek Dam in Tajikistan (credit).

Lipman: You talk about repeated re-thinking of the industrialization strategy. When the chosen strategy was not working, the masterminds of industrialization began to think of another approach. Do not the “First World” and the “Second World” share this dynamic of moving from one stage to another?

Kalinovsky: I think that’s right; you also end up changing even the definition of development or modernization. The questions that you ask are: what were the commitments made by the Soviet state? The Soviet Union promised to lift everybody up to a certain level of material well-being, and then they had a debate about the best way to get there.

But then you come face to face with the fact that your paradigms are not working. For instance, you start off with a presumption that peasants are going to flock to industry because it offers somewhat better wages and better conditions. But then the peasantry don’t do it, so suddenly you have to say, oh, what is this peasantry all about? It is interesting that Central Asian scholars also made this presumption. Some of them were born in the countryside, and I suspect that, in part because they had made their own “move into modernity,” they expected everybody else to follow. But they did not! Then these scholars said, we need to go back to the countryside and study what these people actually want.

|

“This coincides with the period in the USSR in which sociology was being re-established as a discipline. It turns out that Central Asians don’t want to move to the cities, they still want to have large families and lots of space, and they believe that it is very important to be close to their parents.”

|

This coincides with the period in the USSR in which sociology was being re-established as a discipline. What you see is sociologists and other scholars going out to the countryside and doing this research in order to understand: what is it that people want, why aren’t they moving, what would they prefer to do, what do they need? And that led them to say, wait a minute, we had our priorities wrong. It turns out that they don’t want to move to the cities, they still want to have large families and lots of space, and they believe that it is very important to be close to their parents.

The conclusions the Central Asian scholars drew were in some cases very different from those that some people in Moscow started to draw. In Central Asia they said, first, we need to work on the consciousness of these people, we need to work on their culture, and that meant, first and foremost, delivering the welfare state to the countryside, making sure that you have good schools and good healthcare, and also maybe bringing industry closer to where people lived.

In Moscow, what you see among some of the European scholars within the Soviet Union is a discourse that people are, in fact, different. This discourse emerged slowly, but by the late 1970s and early 1980s it was very much there. While they had always assumed that Central Asians and Europeans and everybody else would move through the same stages of development, maybe, in fact, that was not true. Maybe, the discourse went, we should not waste our investments and force people to do things that are not natural to them.

Lipman: Wasn’t this concept, that maybe people were different, a bit dangerous ideologically? Didn’t it sound somewhat colonial?

Kalinovsky: Yes, I think it was fundamentally dangerous. I think the Soviet Union clearly retained some features of an empire, yet to the extent that it claimed to be a post-colonial state that had done away with the empire and was building something new, the idea that everybody would move from one stage to another and end up in the same place was very central to the Soviet ideology. If you got rid of that, what were you left with? Well, then you were faced with a kind of difference that very quickly became overtly hierarchical. And then the system started to become much more obviously colonial. Moreover, the rationale for maintaining a union started to fall away. For if we are not all moving in the same direction, how do you justify Tajiks and, say, Estonians being in the same state?

Lipman: Did anybody dare articulate it this way at the time? That if some people are different, then what is our whole grand project about? Or is it just the way you articulate this now?

Kalinovsky: Еssentially, that is my interpretation. If you look at the discourse that was beginning to take shape within some of the technocratic organizations, especially in the late 1980s, the Baltic states very openly said that their interests were very different from the interests of the Central Asians. The Baltics said that they did not want to subsidize everybody else. The Central Asian states had a much bigger problem with this, because, of course, that meant giving up on the developmentalist approach. I think the implications were very dangerous. I don’t think this was what caused the collapse of the Soviet Union—especially because I believe the collapse originated in the center, not from the periphery—but it certainly contributed to loosening the ties that held it together.

Leonid Brezhnev tours Tajikistan (credit).

Lipman: There were probably features of the Soviet system that supported the modernization project. One of them was universal conscription, another probably focused on what is referred to as kulturnost, and in your book you also mention a historical phenomenon: those who were evacuated to Central Asia during World War II and the refugees. These factors were conducive to modernization—and weren’t they different from what the United States faced in the “Third World”?

Kalinovsky: These kinds of migration, forced or unforced, were probably quite particular to the Soviet Union, although one can argue that there was a parallel phenomenon in the “Third World”: the way the European colonial еmpires moved their populations around, or people from India moving to other parts of the British Empire—often people who had particular skills or filled some kind of economic niche.

There were several kinds of migration to Central Asia. Of course, you have the war refugees from the European parts of the USSR, some of whom ended up staying in Central Asia after 1945. But you also have two other groups: firstly, all kinds of intellectuals, who were sometimes the people who fell afoul of the authorities in Moscow or somewhere else. In Central Asia, which needed educated, highly qualified cadres, the authorities were more willing to protect them and give them some room. So we have people such as Aleksandr Semenov, a very famous Orientalist who was allowed to re-establish himself in Tajikistan. There were also quite a few others, for example, Jewish doctors or professors of medicine who had a hard time in Moscow or Leningrad and ended up in Tajikistan in 1948 or the early 1950s [when Stalin launched a campaign against “cosmopolitans”—that is, Jews]. In many cases, these people formed quite good relationships with the new elite that was being trained in these republics, and many of them ended up staying there for their whole lives and sometimes for multiple generations.

Secondly, with these big industrialization projects, there were also skilled workers—engineers—who came in much larger numbers. In some ways, that was more controversial: these people needed housing and they very often ended up getting priority housing in the newly expanding, newly created cities that were part of the industrialization program. So suddenly you had this European population dominating cities that were supposedly built for Tajiks or Uzbeks or Kyrgyz. What was presented as part of the great process, with everybody learning from, and helping each other, in fact caused a fair bit of tension.

|

“Whenever I interviewed men, I always talked to them about their experience in military service. For the most part, they saw it as part of becoming Soviet, and some saw it as part of becoming a man. Very often, it was also a conscript’s first experience outside of his home region.”

|

The military is an interesting theme, because Sovietologists in the West used to be quite obsessed with this question: what did Central Asians mean to the Soviet military? Those looking for a weak link in the Soviet chain thought this was one of them, particularly in the late 1970s. At that time, the argument was that the Central Asian population was growing much faster than that of the European USSR, and some scholars assumed that the Soviets were worried about their military becoming increasingly dependent on Central Asians who might be not fully loyal.

In fact, the original question that led me to study Central Asia, connected to my first book, A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan, was precisely the role of Central Asian soldiers in the Soviet-Afghan war. It is true that the Soviets relied very heavily on Central Asian officers, soldiers, and especially translators during that war. Yet contrary to what many in the West thought, they were loyal, although some of them came away very disenchanted with the Soviet system. Others, however, came away very proud of their service.

Whenever I interviewed men, I always talked to them about their experience in military service. For the most part, they saw it as part of becoming Soviet, and some saw it as part of becoming a man. Very often, it was also a conscript’s first experience outside of his home region. A young man was thrown together with those of different nationalities, and, of course, it could be quite a culture shock—for instance, using mat [profanity] was quite common for Russian soldiers, but completely shocking to the Central Asians conscripts.

There is an interesting parallel here with U.S. development approaches. One of the reasons why the United States arguably supported a lot of military modernization projects was because the military was seen as a national institution that could create a citizenry and enable an individual to see himself as not just a peasant from a certain location or a speaker of a certain language, but a member of a nation. You also see this in USAID programs and in the various alliances for progress in Latin America. You see this among post-colonial elites, who rely on the military. In part, this is a matter of security; in part, it is a way of protecting yourself from neocolonialism. But it is also seen as one of the most efficient ways of creating a citizenry.

Tajikistan’s capital, Dushanbe, in Soviet times (credit).

Lipman: You are saying that military service as a modernization factor was not unique to Russia. How about the dissemination of culture and the concept of kulturnost, including the unified curriculum throughout the Soviet Union, from the Baltics to Tajikistan and Turkmenistan? Was that a factor that distinguished the modernization of Central Asia from postcolonial modernization?

Kalinovsky: The concern with culture and its link to modernization was certainly part of American social science debates in the 1960s and 1970s, so maybe this factor in itself was not so different either. You bring this notion of kulturnost to these far-flung parts of the former Soviet empire and you’re telling people how to dress, what kind of families to have, etc. And then the challenge is: how is this not an imperial policy? You’re beginning to introduce art forms, such as opera or the novel, which might not be desired art forms for the local people. How is that not an imperial project? For me, the most interesting thing was always the tensions and the contradictions of how these issues worked out.

Lipman: Which brings us to the issue of Islam. You write that the Soviet government, nominally atheistic, showed tolerance toward people in the Muslim republics, in particular Tajikistan. Muslims in the Soviet Union could attend “clubs” that sometimes doubled as mosques. Would you please talk about this?

Kalinovsky: I’m not the first one to note this. When you look at what happened on the ground, you realize that local organizations, such as “clubs,” had different goals and priorities. Well, they were getting the dam built, getting the city built, delivering water and electricity; they were also drawing local people into the workforce. But if you draw local people into the workforce and you are not using the threat of terror to get them to behave in a certain way, then you have to find some way to accommodate them, even if these people are not members of the Communist Party. You need the support of these villagers, you need their land to make things happen, to get things built. This is when local arrangements take shape. And you see that officials do think their way through this, and they have to say, okay, this is not the ideal world that we are working towards, but it’s good enough for now.

In order to make things work, you have to set priorities. What is more important: to keep these people from praying or to have good citizens who work on a project and are a model for others and can maybe even inspire others to follow their path?

Lipman: We’ve been talking more or less about achievements: building dams, building cities, and even showing tolerance so Muslims can be models for others. There were evidently negative aspects of modernization, not just in the Soviet Union, but also elsewhere. By the end of the Soviet project, Tajikistan was still the poorest republic in the Soviet Union. How do you see the “balance sheet” after several decades of post-Stalin modernization?

|

“Notions of success and failure tend to be very subjective.Yes, Tajikistan was the poorest republic of the Soviet Union in the end, but had certainly improved on some measures from where it had been at the start of this project in the 1950s.”

|

Kalinovsky: To be honest, I have given up on drawing a balance sheet. At a certain point, I stopped talking about success and failure altogether, because ultimately notions of success and failure tend to be very subjective. Yes, Tajikistan was the poorest republic of the Soviet Union in the end, but had certainly improved on some measures from where it had been at the start of this project in the 1950s. So what do we want to emphasize? Is it how many people were graduating from school and the dynamic of life expectancy? Or do we want to point out the relative quality?

That’s actually part of a much wider debate in development studies and among development economists, because it has political consequences as well. If you’re an economist, you can compare income levels, etc., and that’s fine, but if you’re a historian, you have to wrestle, in a sense, with the very complicated reactions that people had as the Soviet Union came to an end.

What bothered people [in Tajikistan], those who began to mobilize at that time—not necessarily against the Soviet Union, but around many different issues—was precisely that whatever measurable progress had been achieved, the promises had not been fulfilled, and in some cases the negative effects were such that whatever progress had been made, it was not worth it. The environment was probably the most obvious negative effect.

|

“A presumption that all those planners had in common, starting from the late 1940s, but particularly in the 1950s, was that Central Asia would keep producing lots of cotton, that production would increasingly be mechanized. However, that never happened.”

|

A presumption that all those planners had in common, in the late 1940s and through the 1950s, was that Central Asia would keep producing lots of cotton, that production would increasingly be mechanized. However, that never happened. The production of cotton continued to rely on manual labor, particularly female and child labor. This had horrific effects on health and schooling that undermined the very kind of modernization program that the Soviet Union was supposedly promoting. And the environmental problems that were caused by growing cotton were also immense, because—and this is connected to the dam projects—when you dam rivers, you also stop a lot of nutrients from flowing into the soil. At the same time, since you are pursuing a very intensive agricultural production policy [trying to get more crop per acre], you end up using a lot of artificial chemical fertilizers. The fertilizer then seeps into the ground water, and this starts affecting people’s health. Also, some waters do not reach their destinations, so we get tragedies such as that of the Aral Sea, which has steadily shrunk. It is not that people or officials were unaware of the problems. From the 1950s on, officials tried to find solutions, but because the main priority was the fulfillment of production quotas, environmental issues were always on the back burner. It is also true that I am speaking from today’s contemporary concern for the environment. But the environmental effects alone are the reason why I would not want to draw up a balance sheet.

Some of the grievances voiced by the Central Asian intelligentsia in the late 1980s were classic post-colonial complaints about the loss of one’s own culture. For me as a historian, this is much more problematic. One of the frequently raised claims was that “nobody speaks our language any more.” But that was nonsense—this claim was simply not legitimate! Something like 70 percent of Tajiks did not speak Russian properly, but they certainly did speak Tajik. Now, maybe they didn’t speak the kind of literary Tajik that the intellectual elite wanted them to speak, but they certainly knew their own language. That’s another reason why I am wary about putting them on a balance sheet and saying, this was good about the Soviet Union and that was bad.

Lipman: You mentioned the late 1980s—the perestroika era, when the focus was on exposing all the negative things associated with the Soviet decades. Of course, Tajikistan was no exception. At the time it looked like people only thought and spoke about negative things, not any of the achievements. And yet closer to the end of the book, you say that the Soviet experience should teach us humility. What do you mean by that?

|

“We should be saying, ‘the Soviet Union tried a lot of things that Western development agencies usually didn’t have the willingness or capacity to do in a comprehensive way.’

|

Kalinovsky: While doing research in Tajikistan, I observed Western aid organizations at work. When you look at Western European and American development policies, you see that in the 1970s—around the same time as the Soviet Union began to rethink its own modernization policies—there was a turn away from big development projects and a heavier focus on the little things. You see a proliferation of small agencies working on small projects, such as very small-scale infrastructure projects and so on.

When you look at the Soviet project, you realize that they tried to do everything at once and the results were unsatisfactory from the point of view of many people. So rather than saying, “oh, the Soviets were doing something socialist and they were crazy atheists, so of course their projects didn’t work,” I think what we should be saying is, “the Soviet Union tried a lot of things that Western development agencies usually didn’t have the willingness or capacity to do in a comprehensive way.” Instead of an outlook of, “we have nothing to learn from their experience,” we should perhaps be more humble and say, “a whole project of transforming people’s lives, sometimes radically, can just be very hard to pull off.”

Artemy M. Kalinovsky is Senior Lecturer in East European Studies at the University of Amsterdam. He is the author of Laboratory of Socialist Development: Cold War Politics and Decolonization in Soviet Tajikistan (Cornell University Press, 2018) and A Long Goodbye: the Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan (Harvard University Press, 2011).