Is Milorad Dodik, the recently re-elected president of Republika Srpska, the Serb entity within Bosnia & Herzegovina, a Russian proxy force? Many Euro-Atlantic officials and politicians in that region certainly think so. Dodik has cultivated close ties with President Vladimir Putin for years. Both men meet frequently—most recently on May 23, 2023—and actively support each other. His trips to Russia, his frequent meetings with the Russian ambassador, his resistance to sanctions against Moscow, and his open support for Russia’s annexations in Ukraine have contributed to the belief that he is a dangerous Russia-aligned actor in Europe. The medal of honor that Dodik bestowed upon Putin as the one-year anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine approached reinforces this perception. Potentially damaging to Dodik’s election plans, the invasion instead became a successful foundation for his own political strategy.

But commonplace explanations of Dodik as Putin’s client in the Balkans miss the mark. Close analysis of his post-Ukraine embrace of Putin points instead to an alternative argument: not Dodik as a Putin loyalist, but Dodik as a skilled populist politician who, as he has done throughout his career, turned international antipathy to his electoral advantage.

Dodik and the Invasion of Ukraine

The news of the Russian invasion of Ukraine came as a grim omen to many in Bosnia & Herzegovina. As the European Union Force Bosnia & Herzegovina (EUFOR) increased the number of its troops there the same day, the connection between Putin’s launch of war and Dodik’s secessionist moves seemed evident. The warmongering discourse that had dominated Bosnia’s media landscape for six months before now appeared as more than mere talk.

A number of Bosnian officials claimed Dodik must have been informed of the “special operation” in advance and instructed by Putin to pursue a de facto secession for Republika Srpska as a next step to the invasion of Ukraine. Indeed, fear of the return of war and territorial fragmentation in Bosnia dominated in the first days of the invasion. But disagreements within Bosnia’s rotating presidency over the war slowly displaced this fear. Whereas Bosniak and Croat officials in Bosnia & Herzegovina were quick to condemn the invasion and side with the EU on the matter, Dodik insisted on Bosnia remaining neutral. The Bosnian public broadly understood Dodik’s statements as tacitly supportive of Russia. To his critics, this stance further confirmed his destabilizing presence in Bosnia, the Balkans, and Europe.

Dodik’s rhetoric on Ukraine shifted toward explicit support for Putin’s positions in June 2022. The war was a “special military operation” through which Russia was only protecting its people in Donbas, a defensive move in the face of the collective West’s plan to destroy Russia and take its natural resources. This shift was not a surprise for Bosnia’s pro-Ukraine public and officials. But some went further and charged that Dodik was a puppet of Putin who could not say “no” lest there be a disastrous price to pay. Dodik’s politics were, they charged, made in the Kremlin, and he operated as a low-cost agent of Russia thwarting further NATO expansion in the Balkans.

Over the course of 2022, Dodik persistently opposed sanctions against Russia and held frequent meetings with the Russian Ambassador to Bosnia & Herzegovina. He publicly supported referenda in Donbas, met twice with Putin and once with Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and attempted to block Bosnia & Herzegovina from voting in favor of the UN resolution condemning Russia by backchanneling through the Russian Ambassador to the UN.

However, this argument overlooks two important facts. First, Dodik’s initial adherence to neutrality was a contingent response to the immediate aftermath of the invasion. While demonstrating to his supporters that he was standing up to the pressures of the West, he was also preserving options and calculating new redlines as the first few months of the war played out. Second, the shift in his rhetoric surrounding the invasion of Ukraine and meetings with Putin only took place after he had announced he was going to run once more for the presidency of Republika Srpska and not as the Serb candidate for the three-person Bosnia & Herzegovina presidency. He was president from 2010-2018 and twice served as prime minister (1998–2001 and 2006–2010) and chair of the presidency of Bosnia & Herzegovina (2018-2019 and 2020-2021).

Dodik’s rallying to Russia geopoliticized the race for the Republika Srpska presidency. Embracing Putin, now a war criminal in the eyes of the West, was a strategy that allowed the three-decade careerist Bosnian Serb politician to replay the script that served him well down the years: the heroic defender of an embattled entity and community against the sneering elites of the West and their servants in Bosnia.

Dodik’s Election Campaign: Melodrama and Putin Pictures

Dodik’s insistence on Bosnia’s neutrality toward the Ukraine war set the stage for an election campaign centered around his ties to Putin. He legitimized his stance by claiming that “picking sides” was unconstitutional and neutrality was the only law-abiding move. There were obvious double standards, he told his target audience. If the collective West had never been condemned for decades of breaking international law in Bosnia & Herzegovina and beyond, then neither should Russia be condemned for its “defensive” actions in Ukraine amid global turmoil. With regard to sanctions, he had only either stated his opposition or denied that Bosnia aligned its foreign policy with EU sanctions against Russia.

Dodik’s rallying to Russia’s cause in Ukraine obscured domestic setbacks. Soon after the launch of the invasion, the Bosnia & Herzegovina Prosecutor’s Office summoned him over the origin of funds for his 2007 purchase of a villa in Serbia. The Office of the High Representative (OHR) annulled the Republika Srpska Law on Immovable Property shortly after, and the UK imposed sanctions against Dodik. This was followed by Dodik’s request to veto the Bosnia & Herzegovina presidency’s earlier resolutions failing to secure a majority vote in the National Assembly. As he announced a delay in the transfer of Bosnia & Herzegovina state authorities to Republika Srpska, an idea he championed for months, it compelled local media to speculate that his political power was waning, his career finally over.

Dodik’s camp responded with melodrama. Because of his stance on Ukraine, his enemies were planning to kidnap him! Rumors that NATO, EUFOR, and British Specialist Forces were coming for him were splashed across the front pages of the local Dodik-friendly tabloid press. The Republika Srpska Ministry of Interior Affairs responded by sending armored vehicles to guard his office and home: another front page picture. The story resonated with his supporters, who bought into his long-standing conflation of his welfare and Republika Srpska statehood.

Dodik’s campaign worked up a cocktail of affect around the issue that culminated with a gathering of nearly 20,000 people in Banja Luka who rallied in support of him and in protest of the OHR decision to annul the property law. Less than a month later, he announced he wanted to be Republika Srpska’s president again.

Dodik’s rallying to Russia against Ukraine signaled a calculation that geopoliticizing the election was his best electoral strategy. It was also a way of casting himself as a victim of geopolitics, not corruption investigations. Russia was happy to play along. He jetted off to meet with Putin and Lavrov in Moscow in June 2022. Pictures of their meeting consolidated Dodik’s image as both an international statesman and a defier of the West (like Viktor Orbán and Recep Erdoğan, who also met Putin before their elections).

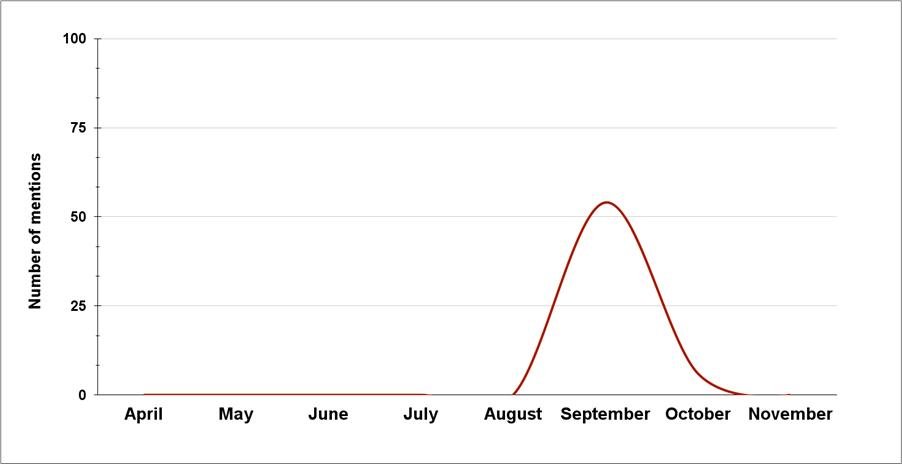

As election day came closer, Dodik pushed this strategy further. He met Putin again in September 2022 (a day before Putin’s executive order on mobilization) and incorporated video excerpts of their previous meeting into his election campaign video. The politician’s supporters wore t-shirts depicting him and Putin shaking hands. His personal-public website became saturated with articles emphasizing his kindred and productive ties with Putin. The word frequency count from his website in Figure 1 shows that Dodik’s mentions of Putin were exceptionally high during his one-month election campaign in September.

Figure 1. Mentions of Putin on Dodik’s Personal Website, 2022

Conclusion

To most Europeans, Dodik’s embrace of Putin amid the invasion of Ukraine was infuriating. But Dodik knows his electorate well. His opponent, Jelena Trivić, dedicated her entire campaign to exposing instances of Dodik’s corruption and wrongdoing, attempting to cast him as a traitor to the republic and an embodiment of misguided politics. The election was close, and the result was clouded by fraud allegations. Dodik’s triumph was confirmed a month later: he officially won by 27,000 votes from a total of over 600,000 votes cast. King Mile—as he is called locally with a play on his first name—the master of defiance, had rallied around Putin’s Russia and won.

Leaders across Europe claim Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a transformative event. A broad test of whether that is really the case is already underway in the Balkans, in Bosnia, and in Kosovo, where geopolitics is always a useful invisibility cloak for power and corruption.

Emina Muzaferija is a PhD Student and Gerard Toal is Professor of Government and International Affairs at Virginia Tech (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University).