Volodymyr Zelensky’s party received overwhelming support. See the full map below.

The Parliamentary election in Ukraine brought resounding victory to the Servant of the People (SoP) party put together around the newly elected president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Sergiy Kudelia analyzes the results of the parliamentary election and the risks associated with the sudden dominance of the pro-presidential party.

President Zelensky pursued two immediate goals when he announced a snap parliamentary election during his inaugural address in the Rada. First, he sought to maximize the share of parliamentary seats controlled by his political party, SoP. Second, he wanted to reinforce his image of a political disruptor bent on sweeping away the old political guard. On both counts, he hit the mark. His party list received 43.16 percent of the votes, while its candidates won in 65 percent of the single-mandate races. For the first time in Ukraine’s political history, a single party will now control the majority of seats in the parliament. Meanwhile, in July, for the first time in at least a decade, the share of Ukrainians who thought their country was moving in the right direction (41 percent) exceeded the number of those who thought it was on the wrong track (37 percent). Finally, Zelensky’s approval has remained steady since his inauguration with 58 percent of respondents fully or partially satisfied with his activities.

However, the key downside of an early election—the haphazard manner of composing party lists and selection of poorly vetted candidates—will affect both the efficacy of the new parliament and the president’s ability to carry out his central promise of cleaning up the system. While the parliamentary election gave Ukrainians a chance to “kick the rascals out,” it brought to the new parliament a largely inexperienced crowd united only by the superficial “Ze!” brand and tied to the whims of its leader.

The Campaign: It’s all about “Ze!”

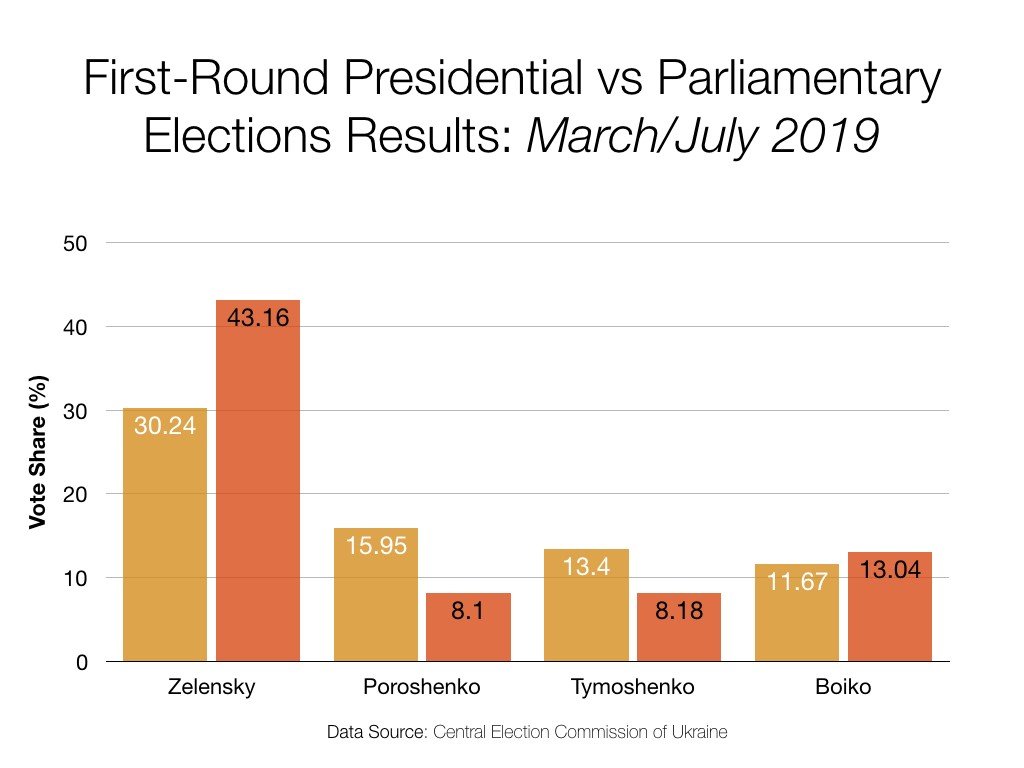

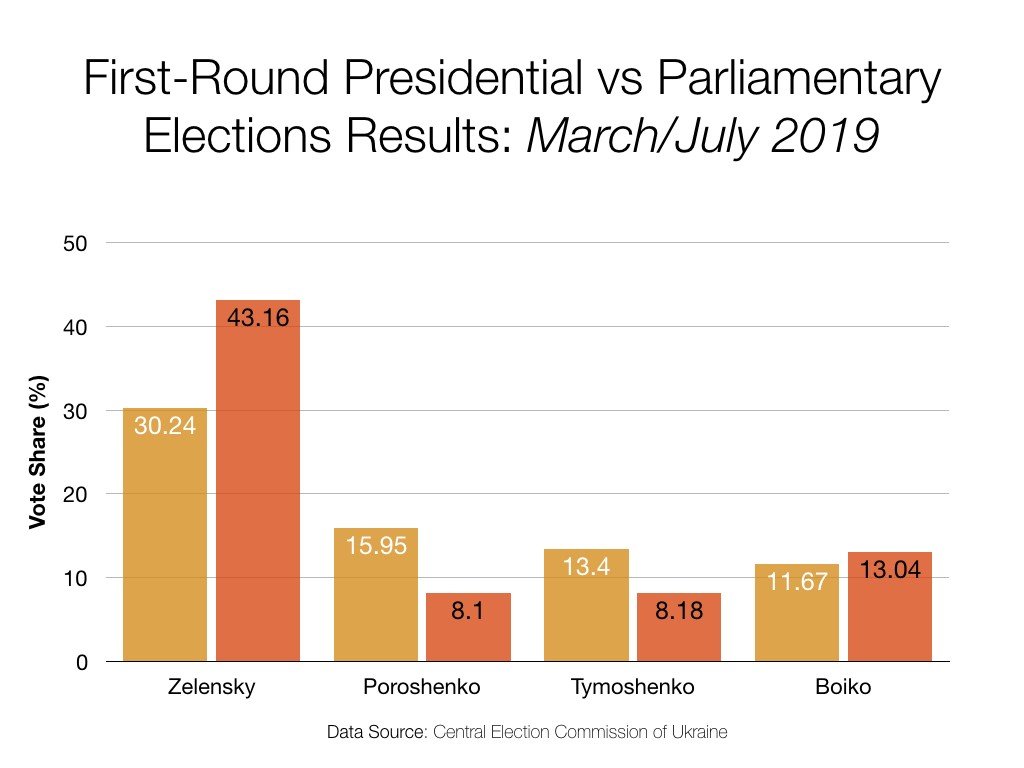

The sprint-like parliamentary campaign strongly advantaged well-known political figures who earlier had contested the presidency. As a result, each of the top four presidential contenders—Zelensky, Petro Poroshenko, Yulia Tymoshenko, and Yuri Boiko—managed to lead their parties into the parliament. However, their respective parties’ vote shares were substantially different from their individual results (see Figure 1). While Zelensky’s party gained everywhere across Ukraine compared to his own first-round results, Poroshenko’s and Tymoshenko’s parties received less than half of the votes of their respective leaders. Three key features of the campaign may explain this divergence.

First, Zelensky effectively framed the parliamentary election as a “third round” of the presidential vote, thus extending the anti-establishment logic of his campaign to the parliamentary contest. His central claim was that a radical overhaul of the system was possible only with a like-minded parliament dominated by a pro-presidential force. His frequent and fiery squabbles with the outgoing coalition, that sought to block his ministerial appointments and torpedo the bills he had submitted to the Rada, accentuated the need for a complete revamp of the legislature. This further concurred with the prevailing mood of the society characterized by strong anti-incumbent sentiments.

| “In many parts of Ukraine Zelensky’s party did not even run candidate-centered campaigns, its ads reduced to just the generic “Ze!” |

Zelensky channeled the public rejection of the status quo by turning his visits to various regions across Ukraine into pillorying sessions in which he dressed down local officials and forced them to resign. His initiative to lustrate all top government officials and MPs who served in the post-Maidan period pursued a similar goal of taking revenge on behalf of the aggrieved public. The hallmark of Zelensky’s parliamentary campaign, however, was the conversion of his personal “Ze!” logo into a universal trademark symbolizing Ukraine’s new anti-establishment wave. As a result, the use of this brand became a springboard into parliament for dozens of obscure candidates nominated by the SoP. In many parts of Ukraine Zelensky’s party did not even run candidate-centered campaigns, its ads reduced to just the generic “Ze!.”

Secondly, only two major parties based their campaigns on direct criticisms of the new president. One, Opposition Platform–For Life, attacked Zelensky for failing to adopt a more conciliatory approach regarding Donbas and for maintaining a confrontational rhetoric in relations with Russia. Its leaders, Yuri Boiko and Viktor Medvedchuk, campaigned on the promise of starting direct talks with Moscow to settle the conflict in Donbas and fully restore economic ties with Moscow. They portrayed Zelensky as “Poroshenko-lite,” accusing him of breaking his promise to end the war for fear of a nationalist backlash. This message was emphasized on three TV news channels controlled by Medvedchuk and now used as mouthpieces for his political force. Moreover, the Kremlin further elevated the standing of Opposition Platform–For Life over a competing party, Opposition Bloc, by organizing a meeting between Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and the leaders of the Opposition Platform–For Life thus clearly signaling its preferences.

Figure 1: Vote share for the presidential candidates in the first round of presidential election (yellow) (March 31, 2019) and for their respective parties (orange) in the parliamentary election (July 21, 2019).

Poroshenko’s re-branded European Solidarity party initiated attacks against Zelensky from the nationalist side. It presented Zelensky as a threat to Poroshenko’s key nation-building achievements, such as the language and decommunization laws, and weak on national security, particularly on resisting Russian aggression. Poroshenko issued frequent public appeals contradicting some of Zelensky’s statements and chastising him for his various initiatives—from the proposal to hold regional referenda to the initiative of lustrating all top officials who had served during the previous five years. He also frequently invoked the term “revanchism” as he pointed out that a pro-Zelensky majority in the Rada is fraught with risks implying that Zelensky acted on behalf of pro-Russian oligarchs and political forces whose goal was to return to the policies of Yanukovych’s era.

|

“The Servant of the People party gained in popularity most significantly in Western Ukraine where Zelensky had earlier shown the weakest results in the presidential poll.” |

Ultimately, the attacks on Zelensky from the pro-Russian side proved to be more compelling politically than the attacks from the nationalist right. Contrary to Poroshenko’s earlier catastrophic predictions, Zelensky’s election did not lead to the loss of Ukraine’s sovereignty. Meanwhile, the new president issued several acerbic appeals to President Vladimir Putin untainted by the servile attitude that many Poroshenko voters expected to see. By contrast, there was no substantive change in Ukraine’s policies regarding Donbas, and the new administration did not attempt to articulate a new strategy of settling the conflict. Zelensky also avoided expressing direct opposition to the recently adopted language law or other policies associated with the ethno-nationalist bias of the previous administration. As a result, the SoP party gained in popularity most significantly in Western Ukraine where Zelensky had earlier shown the weakest results in the presidential poll.

Thirdly, the campaign dynamic was affected by the emergence of the new party “Voice” that was formed by famous rock singer Sviatoslav Vakarchuk. Although Vakarchuk had been long regarded as a potential presidential candidate, he never joined the presidential race, but implicitly campaigned against Zelensky having coined a hashtag line “Voting is not a prank.” However, just as Zelensky earlier, he jumped at the opportunity of exploiting his celebrity status for political gains. He similarly tried to ride the anti-incumbent wave by publicly refusing to include in his party list any current or former MPs, even though he endorsed a number of them in single-district races. At the same time, his party list included many former officials who worked in previous governments in various capacities—from deputy ministers to advisors to Yatsenyuk and Hroysman cabinets. Vakarchuk also borrowed from Zelensky a strategy of attracting potential voters by staging free performances of his band in every city where he appeared for a campaign event. In contrast to Zelensky, however, Vakarchuk’s platform was closely aligned with Poroshenko’s, both in terms of its nation-building priorities and an emphasis on neoliberal reforms. As a result, his appeal was limited to Western Ukraine where he campaigned most intensely, visiting both major cities and smaller towns (while never visiting any cities in Donbas). This pitted him against Poroshenko’s own party which viewed Western Ukraine as its base and put the two in unusual direct confrontation weeks before the final vote. However, Vakarchuk’s sudden ambivalence regarding Zelensky whom he now viewed as a potential coalition partner strongly contrasted with Poroshenko’s own clear anti-Zelensky stance. This clarity in positioning ultimately gave Poroshenko an edge among those in Western Ukraine who remained suspicious about Zelensky’s true colors and wanted to establish a stronger counterweight against him in the parliament.

The Results: Kicking the Rascals Out

The parliamentary election of 2019, despite its relatively low turnout (49.9 percent), produced a momentous reordering both of Ukraine’s electoral map and the parliament composition (see Figure 2). For the first time in Ukraine’s history, a single party (SoP) won in 89 percent of the electoral districts based on the party list voting (178 out of 199), while its candidates triumphed in 65 percent of the majoritarian races (130 out of 199). The parliamentary election also improved Zelensky’s first-round result (30.2 percent) by 13 percentage points: the SoP gained 43.16 percent total and won in all but three oblasts of Ukraine (Lvivska, Donetska, Luhanska). In March 2019 Zelensky lost in all three oblasts of Galicia in addition to two oblasts in Donbas. As a result, Ukraine’s electoral map, which has been traditionally fractured among multiple parties and polarized roughly along the Dnieper axis, has become largely unified around a single political force with two minor outliers in the Eastern and Western regions. Even though the old divides still resurface if one looks at the results with SoP excluded from the race (see Figure 3), the intensity of the old “orange-blue” ideological confrontation has largely dissipated. Importantly, SoP came in close second to Vakarchuk’s Voice (22 percent to 23 percent) in Lvivska oblast where it carried most of its electoral districts and won the rural vote. Similarly, it came in second (albeit with a larger gap) to Opposition Platform–For Life in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. This indicates a low level of political polarization in Ukraine, which is highly consequential given its political turmoil of the last decade. It also points to the emergence of a centrist political force that has become acceptable to voters in all regions and across traditional divides. Such result could be attributed to Zelensky’s avoidance of traditional hot-button issues (such as the language or religion) in his rhetoric and his emphasis on the unifying messages, such as the public yearning for an elite turnover, as well as rooting out corruption, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and individual empowerment. This helped to build a new electoral coalition, which cuts across traditional cleavages and seeks primarily to overthrow the “old order” through mass elite purge. “Ze!” as a brand has come to denote an attempt to wipe the slate clean and hand power to anyone untainted by previous political dealings.

Figure 2: First-place winners of Ukraine’s 2019 parliamentary election based on party-list voting, by district.

Figure 3: First place winners of Ukraine’s 2019 parliamentary election by party-list voting with Servant of the People results excluded, by district.

|

“Ze!” as a brand has come to denote an attempt to wipe the slate clean and hand power to anyone untainted by previous political dealings.” |

Almost all the parties that had won seats in 2014, experienced sharp dwindling of public support (see Figure 4). Out of the six parties that crossed the five-percent-electoral threshold in 2014 only two (Poroshenko’s European Solidarity and Tymoshenko’s Bat’kivshchyna) will remain in the next convocation of the parliament. Arseniy Yatsenyuk’s People’s Front, the party that won in 2014 and has been part of the ruling coalition since then, decided not to contest the election or field its candidates seeing its poll numbers drop below one percent. The new party of the current Prime Minister Volodymyr Hroysman received a meager 2.4 percent of the vote, while all those members of his cabinet who decided to run in single-mandate districts have lost their races. Even the once powerful “Opposition Bloc” now led by mayors of the major cities and key associates of the richest oligarch Rinat Akhmetov could not win in any of the districts even in Donbas. The pro-Russian end of Ukraine’s political spectrum is now represented by the new political alliance Opposition Platform-For Life, which came in second all across Southeastern Ukraine. On the opposite end, the newly formed party, Voice, managed to enter the parliament only due to winning in Lviv and faring well in the rest of Western Ukraine.

Figure 4: Vote share for incumbent parties in Ukraine’s 2014 (blue) and 2019 (green) parliamentary elections

The strong anti-incumbent bias has been similarly visible in district contests. Out of 186 current MPs who participated in 2019 election in single-mandate districts only 38 (20.4 percent) won their races. The candidates of Poroshenko’s party who had triumphed in 69 district races in 2014, now managed to win only in two. Moreover, out of 144 incumbent MPs who decided to contest the same district that they had won in 2014, just 33 (23 percent) managed to get re-elected. Many long-time MPs who controlled the same seat for three or more terms were defeated by political novices running under the “Ze!” brand. For example, the president of the Law Academy in Odesa, Serhiy Kivalov, who was an MP for six consecutive terms, was unseated by a 36-year old commercial director of a retail company without a university degree. Another six-term MP and Forbes billionaire Kostiantyn Zhevago, who owns a mining company listed on the London Stock Exchange, was defeated by a 25-year-old public servant. And the owner of a jet engine manufacturer, Vyacheslav Bohuslaev, who has been a four-term MP from Zaporizzhia, lost to a 29-year old professional photographer. Overall, only 11 percent of incumbent MPs managed to improve the 2014 electoral results in their districts (see Figure 5). The support for incumbents dropped on average by 35 percent in the districts they contested again in 2019.

Figure 5: Vote share for incumbent candidates in single-mandate districts in 2019 parliamentary election compared to their 2014 election results.

Who Governs Now?

In the aftermath of the 2019 election cycle, Ukraine finds itself in an unusual and precarious position. The executive and legislative branches will now be dominated by the representatives of a single political force, which just two months ago existed only in virtual form. They will be increasingly staffed by people who owe their positions to the talents of a single man—Volodymyr Zelensky. Key positions in the Office of the President are already occupied by Zelensky’s long-time associates who worked either as producers or script-writers for his entertainment company. Many new MPs recruited by SoP are not just new to politics, but have barely any relevant work experience or meaningful track record of public activism. Notably, a few of them have ties to the entertainment industry and Zelensky’s comedy shows.

|

“In the aftermath of the 2019 election cycle, Ukraine finds itself in an unusual and precarious position.” |

While this may ensure their loyalty and subordination, it is unlikely to produce an effective oversight or qualitative shift in the legislative work of the parliament. Neither Zelensky nor his party have so far articulated detailed policy proposals in key reform areas or any comprehensive vision for the development of the country. Their ideological platform combines mutually contradictory goals of maximum deregulation and small government in line with Milton Friedman’s ideas, while maintaining a “socially responsible” welfare state and pursuing the “progressive capitalism” ideals of Joseph Stiglitz. Being preoccupied with election campaign antics, the “Ze!” team has unveiled no new proposals on moving forward with conflict resolution in Donbas; neither has it adopted any changes to Poroshenko’s policies regarding the conflict. Instead, Zelensky brought back to the negotiating team the very people who in previous years failed to achieve any progress in the Minsk talks. Finally, there is no certainty regarding the composition of the future government or the choice of key government officials, including the speaker and prime minister. So far, there is no transparency in the process of selecting the candidates for these positions, while the selection process, in a manner strongly reminiscent of Yanukovych era, has been monopolized by the president, several top party officials, and members of the Office of the President.

| “Although constitutionally Ukraine remains a premier-presidential republic, the sudden dominance of the pro-presidential party may turn into a de facto presidential regime.” |

Although constitutionally Ukraine remains a premier-presidential republic, the sudden dominance of the pro-presidential party may turn into a de facto presidential regime with limited accountability of the executive or checks on its operation. The country experienced a similar rule only once in 2010-2013 when the Party of Regions and the Communists controlled the majority of seats in the parliament, while the Party of Regions had almost exclusive control over the government. At the time, however, in the Rada there was a strong and vocal opposition which resisted Yanukovych’s most undemocratic moves. The opposition in the new parliament may be much weaker since other parties, such as Bat’kivshchyna or Voice, are seeking positions in the executive and willing to join a super-majority coalition with SoP. Meanwhile, Poroshenko’s high public disapproval will likely prevent his party from having any major impact in the new parliament.

The chaotic nature of governance by the ruling team and its inability so far to come up with a clear vision for national development point to several possible near-term scenarios. In the first one, the accumulation of informal power in the Office of the President may create a temptation to subordinate the government and interfere in its exclusive policy domains. Combined with the strategic weakness of the president and the incompetence or venality (or both) of his direct subordinates this may lead to a major political instability and pressure from below for an early electoral turnover. This would also mean the implosion of the centrist political project and a return to the polarized politics of the previous decade. In the second scenario, Zelensky may select an independent figure for prime minister (with no previous ties to him or his business), agree to ministerial appointments with no connection to major oligarchic groupings, and respect constitutional boundaries between the Cabinet and the president. Rather than directing or interfering in the executive’s operation, the president then would serve as an institutional check on the Cabinet’s policymaking. This scenario is still likely to produce some tension in the intra-executive relations but would open space for greater pluralism and transparency and lead to a more balanced burden-sharing between different groups within the president’s party. In the third possible scenario, Zelensky may delegate full responsibility for the social and economic sphere to a technocratic government and focus on the key areas under his formal purview. The latter include reintegrating Donbas, engaging in multilateral talks with Russia and the West, and adopting sweeping anti-corruption initiatives that would finally bring the “big fish” to account. This scenario may leave some of president’s current associates starving for power, but it may be the only way in which Zelensky can serve his full term and leave a tangible positive legacy.

Sergiy Kudelia is Associate Professor of Political Science at Baylor University and a member of PONARS Eurasia.