► A discussion with Kirill Rogov on the transformation of electoral patterns during the March 2018 presidential elections and the techniques to compensate for the demobilization of the electorate.

Marlene Laruelle: Kirill, can you explain the “three Russias” pattern of voting behavior that you have observed?

Kirill Rogov: Over the course of the past 15 years (beginning with the 2003 elections), we can observe regular patterns in how the Russian regions have voted in federal elections. On the one hand, there is a group of 15-16 regions (mostly ethnic republics, but also several “Russian” regions like, for example, the Kemerovo district) where the incumbent or dominant party obtains an exceedingly high result in the presence of high voter turnout. That is, United Russia wins approximately 80 percent of the vote and turnout is roughly 80 percent of the population. Political scientist Dmitry Oreshkin has described these regions as “electoral sultanates.”

I call this group “Russia-3.” As the very rare independent observers have shown, real turnout in “Russia-3” is likely not significantly higher than the Russian average, meaning that almost half of the votes here are “whipped up.” But this does not prompt any protest or scandal. The political culture of these regions is conservative: here, there are almost no independent observers, civic organizations, or strong regional branches of opposition parties. People here do not see elections as a mode of civic participation.

|

“As far as voting for the presidential party goes, the real differences are mostly in the level of falsification.”

|

On the other end of the spectrum is a group of regions in which the results are much more modest. These are mainly regions with large urban agglomerations. A significant share of the population consumes independent media; there are local independent media and civic activists; and many observers monitor elections. Falsification is relatively insignificant, such that election results more or less reflect the real votes cast. I call this other group “Russia-1.” For example, in the parliamentary elections of 2016, the “electoral sultanates” voted 78 percent for United Russia with an average turnout of 79 percent, while “Russia-1” voted roughly 40 percent for United Russia, with 40 percent turnout.

Between the two there is a middle ground: “Russia-2.” In this section in the 2016 Duma elections, United Russia’s obtained results of 56 percent with 50 percent turnout. The breakdown of this result is very clear in the example of the Nizhny Novgorod district. The third-largest city in Russia, Nizhny Novgorod votes almost exactly like St. Petersburg and “Russia-1” in general, but there is a large periphery where we see something resembling “electoral sultanates,” where turnout and votes for United Russia approach 80 percent.

It is important to underscore that the “three Russias” differ in their preferences. As far as voting for the presidential party goes, the real differences are mostly in the level of falsification, which reflects variations in the degree to which the elites are consolidated and the level of development of civil society infrastructure.

Laruelle: What happened during the March 2018 presidential elections? How did this “Three Russias” model transform into “One-and-a-Half Russias”?

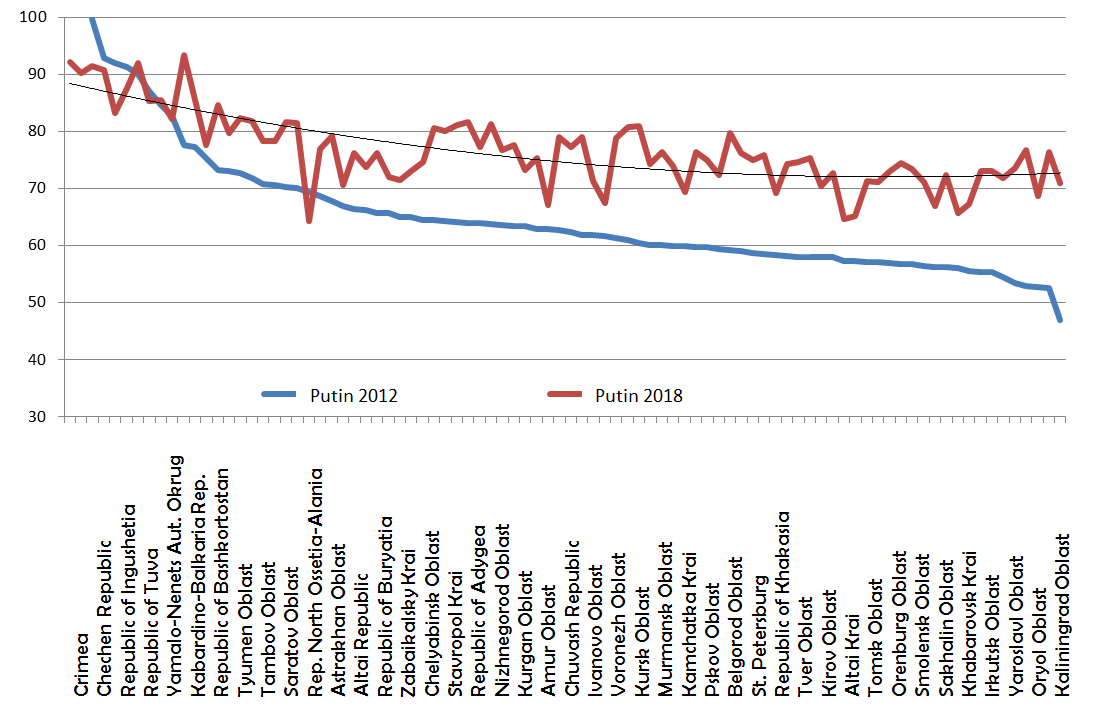

Rogov: In the 2018 presidential elections, the three Russias were reduced to one and a half because “Russia-1” and “Russia-2” nearly disappeared in the electoral sense, with voting patterns suddenly close to the “Russia-3” one. Putin’s results in the country’s main urban centers, former “Russia-1,” were high (up to 65-76 percent), whereas in 2012 the president won only 47-60 percent of the vote. On the whole, if we exclude the annexed regions of Crimea and Sevastopol (around 1.5 million voters), then we see that turnout remained the same in terms of the absolute number of votes for Putin: it rose to 9.6 million, with 6.3 million new votes in “Russia-1.” And this is not the product of falsification. The graph below gives a good overview of the shrinking of “Russia-1” and “Russia-2” in 2018.

Figure 1. Percentage of Votes for Putin, Selected Regional Cross-Section, 2012 and 2018 Elections

Laruelle: So how can we interpret the changes in voting participation in Russia’s urban centers?

Rogov: There are two feasible hypotheses. The first, which appeals to the Kremlin, is supported by a significant number of experts. It claims that the annexation of Crimea, the war with Ukraine, and geopolitical tensions with the West have raised Putin’s popularity to the point that it is equal across society: the capital and the big cities now support the president just as much as the peripheral towns and rural regions do.

The second hypothesis expresses skepticism about that theory and suggests that we are dealing with a new type of manipulation. All analysts, including those in the Kremlin, expected lower turnout. In light of these expectations, a colossal voter-information program was rolled out. Kremlin sources report that a “five points of contact” system was designed for maximum voter coverage: the regional administrations had to ensure that large businesses would secure their employees’ turnout for the election.

|

“Without these manipulations, Putin’s result would have been about 70 percent… The low turnout would have become the main topic of discussion and proof of voter demobilization. The regime needed more legitimacy than previously to confront the challenges ahead.”

|

Nizhny Novgorod’s “five points of contact” strategy, which fell into the hands of a journalist, also mentions the responsibility of employers in big firms to create a list of employees that indicates the number of their polling station, so that the detailed turnout data could be submitted to the local administration by the afternoon. In this way, a hierarchical infrastructure was created for the administration and corporations to get people to the polls. From observers we know that organizational voting (working place mobilization) had a massive effect. For ease of control, people were forced to change their polling locations, were brought in on buses, and photographed their ballots to send them as a record to overseers at their firm.

It is difficult to evaluate the scale of this operation. But there is some evidence: the so-called “early turnout.” All observers noted an unusually large number of people at polling stations during the morning hours. The Nizhny Novgorod method explains this mystery: the overseers had to report back to the administration by 4pm. By noon, average turnout across the country had exceeded that of 2012 by about 5.5 percentage points. On the whole, the phenomenon of “early turnout” can be evaluated at 6-7 percentage points, that is, 7-8 million votes. It could be even higher if the “voluntary” turnout was lower than in 2012 as all experts expected. The shift in the statistics of voting that we discussed earlier can associated be predominantly with this forced turnout.

“Anomalous voting” (identified using the method of Sergey Shpilkin), which we associate with direct falsification, was somewhat lower than in 2012, but made up no less than 8.5 million votes. In all likelihood, another 6-7 million votes were given through administration-corporation enforcement. Without these manipulations, Putin’s result would have been about 70 percent with a turnout of just over 50 percent. Such an outcome would have repeated the results of Vladimir Putin in 2004 and Dmitri Medvedev in 2008; the low turnout would have become the main topic of discussion and proof of voter demobilization. The regime needed more legitimacy than previously to confront the challenges ahead.

Without these manipulations, Putin’s result would have been about 70 percent with a turnout of just over 50 percent. Such outcome would have repeated the results of Vladimir Putin in 2004 and Dmitri Medvedev in 2008; the low turnout would have become the main topic of discussion and proof of voter demobilization. The regime needed more legitimacy than previously to confront the challenges ahead.

Laruelle: In that case, what does the technology of enforced voting mean for understanding the regime’s evolution?

Rogov: Firstly, it reveals the new quality of authoritarian institutions. Previously, the Kremlin did not deploy a centralized administration-corporation voting machine that involved local administrations and managers of large non-governmental enterprises. Second, governors are no longer the exclusive drivers of regional “electoral machines,” as noted by regional specialist Aleksandr Kynev in our collection dedicated to the analysis of elections. The Kremlin created the centralized vertical machine of voter’s working place mobilization.

|

“The Kremlin has thus succeeded in creating the appearance of consolidated support for Vladimir Putin, but, as our analysis shows, it was done to a significant degree by strengthening authoritarian institutions, which compensated for the demobilization of the electorate.”

|

Third, it confirms that Third, it confirms that the Kremlin prefers administrative mobilization to political. As many experts have noted, Vladimir Putin hardly even ran an election campaign, and it was not discussed much on television. There were none of the flashy foreign policy moves typically used to mobilize the population. The results of a January 2018 Levada Center poll give us some insight. In response to the question of what presents the greatest impediment to national development, the leading response was “the regime pays too much attention to foreign policy issues and too little to domestic ones” (31 percent). The next most popular response was the old standby “corruption,” which received only 18 percent. This indicates that the potential of foreign policy to mobilize the people has been exhausted, and the regime understood this.

Along with this, it is worth bearing in mind that enforced voting is a relatively soft form of coercion. People may be forced to go to the polling station, but then they independently vote for Putin. The Kremlin has managed to identify a contingent of the population that does not vote not because it is dissatisfied with the “proposal” or “lack of intrigue,” but because it is not engaged with political agendas. These people, often unskilled workers or employees of various municipal institutions and services, are virtually unreachable by traditional methods of political mobilization. This is a contingent of “Russia-3” living in “Russia-1.” Engaging these individuals enables the government to replace the contingent of “Russia-1” that did not go to the polls. In the 2012 election, alternative candidates of the liberal-centrist variety (such as Sergey Mironov and Mikhail Prokhorov) received 8.5 million votes. In this election, the Ksenia Sobchak-Boris Titov-Grigory Yavlinsky trio received only 2.5 million votes, showing the decrease, at least in voting patterns, of support for the liberal-centrist options.

The Kremlin has thus succeeded in creating the appearance of consolidated support for Vladimir Putin, but, as our analysis shows, it was done to a significant degree by strengthening authoritarian institutions, which compensated for the demobilization of the electorate.

Kirill Rogov is a Senior Research Fellow at the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, a Member of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy, and a Member of the supervisory board of the Liberal Mission Foundation (Moscow). Originally a specialist in Russian intellectual and cultural history of the 18th and 19th centuries, Rogov became a journalist in the late 1990s. In the 2000s, he was Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the news and opinion portal Polit.ru, one of the first Russian online media. He was a Columnist for the leading business daily Vedomosti and later served as Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Kommersant. Since 2007, Rogov has held positions at the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy and the Academy for the National Economy and Public Policy. His recent articles focus on current political development and Russia’s post-Soviet history. He is a columnist for Vedomosti, Forbes–Russia, and Novaya gazeta.

Cover art: Erden Zikibay | Image credits: (c) 2018 Shutterstock