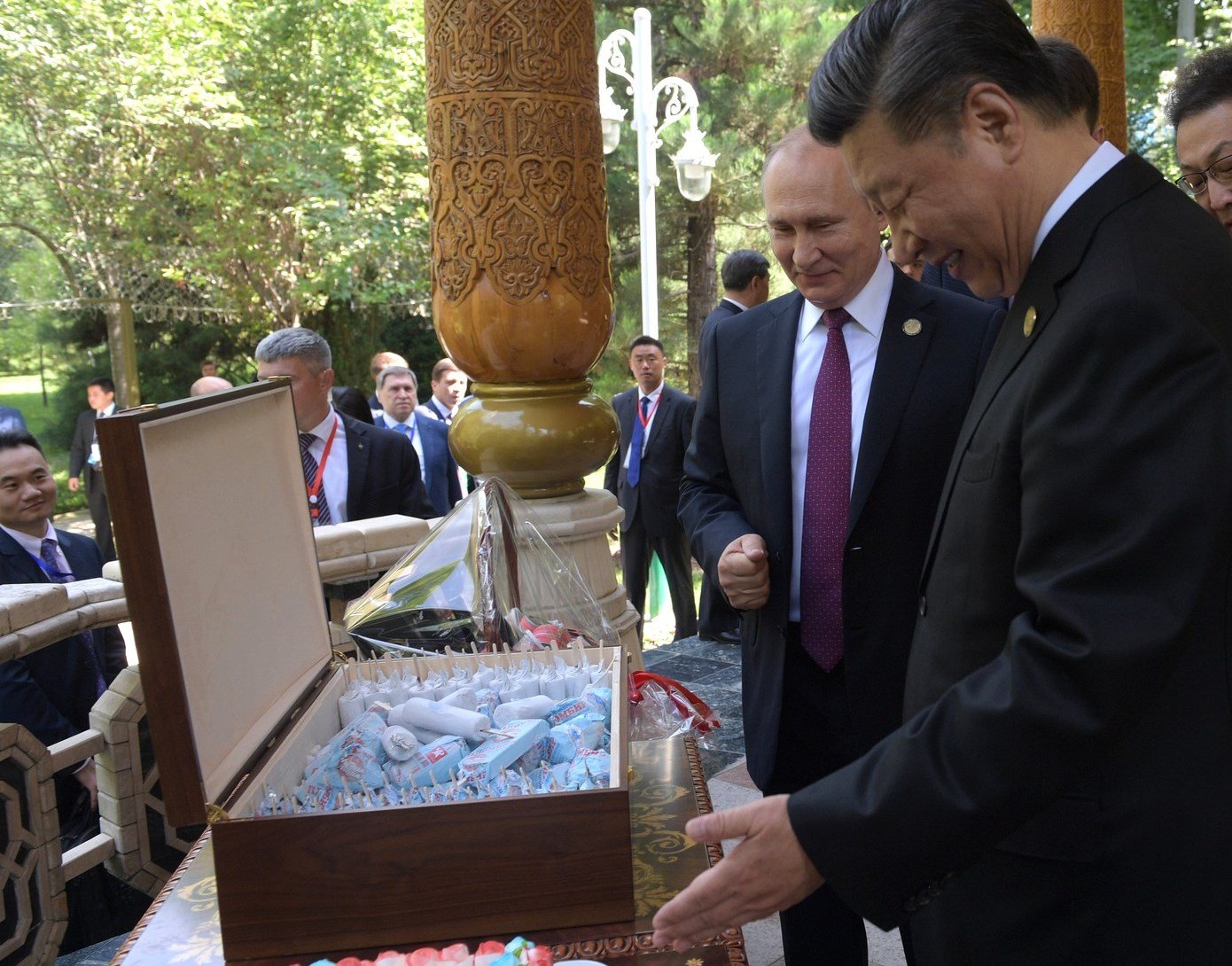

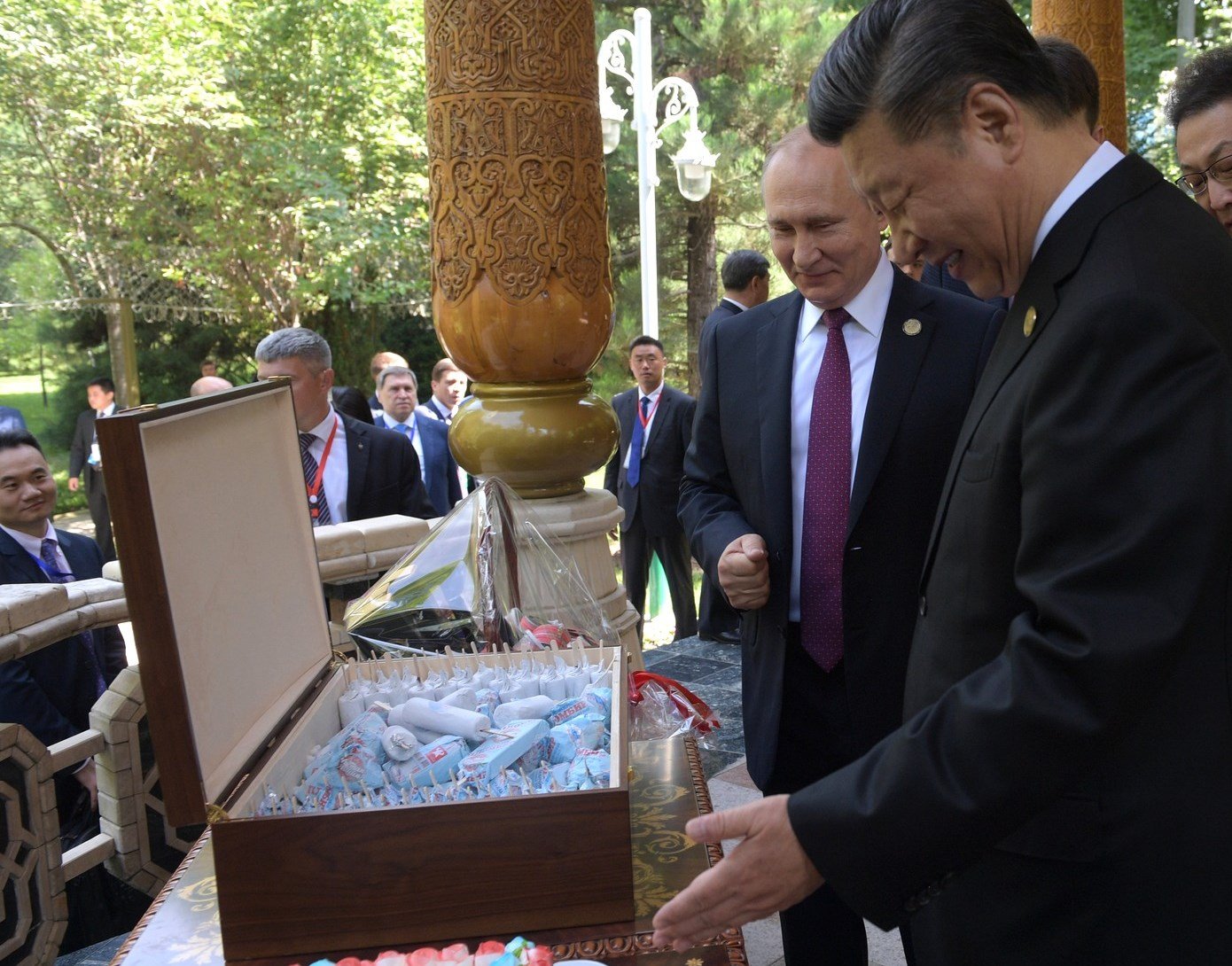

(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) As Moscow and Beijing enter into the 70th year of their relationship since the Communist Revolution in China, what does the apparent bromance between Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin portend for their countries? One short answer: increased Russian ice cream sales in China. Putin’s gift of IceBerry ice cream to Xi in 2016 after the Hangzhou G20 summit led to a 267 percent increase in sales of Russian ice cream the following year.

The display of cordiality, perhaps even real friendship between the two leaders, however, also belies a more fundamental process of mutual learning as well as a common tendency to personalize power at home. At a time when both countries face considerable pressures from the United States, the personal bond between the two presidents has helped insulate the Sino-Russian partnership from many intrinsic challenges. At the same time, the high-level interactions sharply contrast with a lack of bottom-up interconnections, particularly between the border regions of the two countries.

Exchanging Honors and Edibles

In nearly thirty meetings, the two leaders have chosen to highlight their personal chemistry and common interests, from attending hockey games to making steamed buns. Xi, who famously made an impromptu visit to the Qingfeng steamed bun shop in Beijing in 2013 that earned him the nickname Xi baozi (Xi steamed bun), invited Putin to try his hand at making the buns in June 2018 on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation summit meeting in Qingdao. Although Putin joked that his effort failed to meet the Chinese standard, now the Qingfeng bun shop sells Russian IceBerry ice cream, too. On June 15, 2019, as Putin and Xi met in Dushanbe for the SCO summit, Putin brought Xi some more of the ice cream, apparently his favorite, this time to celebrate the Chinese leader’s birthday. (Using the nickname Xi Baozi jokingly on social media earned one Internet user nearly two years in jail. While eating the buns may have been an effort by Xi to cultivate a man-of-the-people image, the term tubaozi or “pumpkin bun” refers to a “country bumpkin,” which is apparently seen as demeaning in this rapidly urbanizing country of former farmers.)

Vladimir Putin offers Xi Jingping a box of his favorite Russian ice cream for his 66th birthday.

On a more serious note, it was Xi who was the guest of honor at the event Putin organized in Moscow in May 2015 commemorating the end of World War II, which other wartime allies refused to attend in protest against Russian actions in Ukraine. Putin returned the favor and joined Xi as the guest of honor in Beijing for the September 3, 2015, military parade marking victory against Japan, a ceremony that Western leaders also avoided for its emphasis on highlighting China’s military might. In 2013, Xi was also the first foreign leader invited to visit the Russian military’s combat command center. On July 4, 2017, Putin awarded Xi Russia’s highest honor, the Order of St. Andrew. Xi replied in kind on June 8, 2018, bestowing on Putin China’s first Friendship Medal.

On June 7, 2019, in a joint interview with TASS and Rossiiskaya Gazeta, Xi commented that he “had closer interactions with President Putin than with any other foreign colleagues. He is my best and bosom friend. I cherish dearly our deep friendship.” For his part, Putin once shared a birthday toast with Xi. The Russian leader later recounted that they shared vodka and sandwiches like university students. In a one-on-one interview with CCTV, Putin acknowledged, “President Xi is the only national leader who has celebrated my birthday with me. I’ve never had such an arrangement or a relationship with any other foreign colleague.” Ahead of Putin’s 2018 interview with CCTV, when China Radio International posted a page on its website, “Who’s a Fan of Putin,” one million netizens responded within a week. CCTV’s online request for questions from viewers for the Putin interview received 24 million views and 40,000 messages.

Similar Leadership Styles that Draw from Each Other

With Xi’s political philosophy and signature Belt and Road Initiative now enshrined in the Chinese Communist Party Constitution, observers in China more naturally compare Xi with Mao Zedong, not to Putin. In 2016, Xi Jinping took on the title of “core leader,” putting him on par with Mao, though Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin also held this honorific. In an echo of China’s Maoist past, there are now songs and even a dance extolling Xi—Big Daddy Xi Loves Mama Peng—though unlike the Mao era, participation is voluntary. At the March 2018 meeting of the Chinese People’s Congress, China’s legislature abolished the practice of term limits that were in place during much of the post-Mao era, effectively making the 64-year-old Xi president for life.

Last year, Putin and Xi both acquired the presidency again, the former for his fourth term overall and the latter for his unlimited second. Xi’s evolution as a political leader draws inspiration from Putin despite their many differences. While Putin is criticized in the West for personal corruption and creating what the late Russia scholar Karen Dawisha termed a “kleptocracy,” Chinese citizens applauded Putin’s 2014 anti-corruption policy requiring state officials to declare their offshore assets. In China, where Xi has been waging an anti-corruption campaign, some say to sideline his political opponents as much as to boost the Chinese Communist Party’s image, a similar policy eventually was enacted three years later.

Regarding restrictions on NGOs, we also see Putin leading the way. In response to street demonstrations prior to his third term as president, in 2012 Russia enacted a “Foreign Agent Law” requiring NGOs to register as foreign agents if they receive any foreign funding. Three years later, another law allowed the Russian authorities to shut down “undesirable” organizations. In 2017 China passed a comparable law that involves strict procedures for registration and oversight of NGOs as well as a ban on their fundraising within China.

In some instances, mutual learning appears to be taking place, as Putin’s Russia emulates the Great Firewall of China, thereby increasing internet censorship within Russia. Together, Russia and China have pushed for “digital sovereignty” at the United Nations and other venues. Echoing Xi’s rhetoric about the China dream, in his March 2018 speech to Russia’s Federal Assembly, Putin spoke of “creating the Russia we all dream about.”

Both Russia and China employ unconventional tactics in conflicts in their areas of interest. We seen both the “little green men” (un-uniformed soldiers) deployed by Russia in Ukraine and Crimea to mask Russia’s official involvement and the civilian militia crews that Andrew Erickson calls the “little blue men“ who engage in provocative behavior on China’s behalf in the East China and South China Seas. China reportedly sent undercover police from neighboring Guangdong province to infiltrate the ongoing pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong, a move that infuriated protestors.

While Chinese tactics hearken back to Sun Tzu’s advice on deception, both Russia and China employ similar incrementalism in their backyards. In the case of Russia’s actions to stealthily expand its territory at the expense of Georgia’s, this has been called “borderization,” while China’s efforts to enhance its presence and claims to sovereignty in the South China Sea have been termed the “cabbage strategy” for China’s “wrapping” of the disputed islands in layers of Chinese fishing boats, militia ships, and naval forces.

Putin is in some ways charting the way for China’s foreign policy shifts, providing a vivid example of a leader who shuns the low profile famously advocated by Deng Xiaoping. Putin’s assertiveness and macho image appears to resonate with the Chinese public, who see him as a modern-day “strong emperor.” After Russia took over Crimea, 76 percent of Russians approved, but 92 percent of respondents to a Tencent poll of Chinese netizens supported the move.

While some of Putin’s more dramatic initiatives may appeal to more nationalist elements of the public, Chinese officials are quick to dismiss their applicability to China. Fu Ying, Chairperson of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, explained the differences in Chinese and Russian foreign policy this way: “In international practices, China and Russia have different styles and focuses… Russia’s foreign policy style is more on the hawkish side, and leans towards the unexpected. This may lead to confrontations and strains in foreign relations.”

Russia, straining to be heard despite sanctions and ostracism from the international community, has little to lose from playing the role of global disrupter. For China, the risks are greater to the extent that Xi seeks to become a global player. Nonetheless, Putin’s policies have provided an alternative approach for Xi to consider as he has sought to make his mark on Chinese domestic and foreign policy.

Both Putin and Xi have embraced a highly personalistic style of leadership, seeking to centralize authority, weaken opposition from within their respective governments and in society, and reward loyal supporters. The impact of their personalism can clearly be seen in Sino-Russian energy relations, where Putin and Xi personally negotiated key deals, such as the Power of Siberia gas pipeline agreement. For Putin, promoting the interests of key supporters was an important rationale for his support for particular projects, and Xi made sure that energy deals rewarded them.

Of course, it is more than personalities and personalism that drive the Sino-Russian partnership. The two leaders have a shared interest in protecting their authoritarian rule, hold overlapping if not identical policy positions on a number of key foreign policy issues, and look to each other for respite from U.S. and Western pressure. Nonetheless, the high-level attention from Putin and Xi to the Sino-Russian partnership, facilitated by their personal interactions, has been important in enabling them to manage the many challenges their relationship continues to face, especially in Central Asia, the Arctic, and in relations between their border regions.

Conclusion

While personalistic ties may enable Putin and Xi to push forward with key deals, over the long run, this will prevent constituencies from forming within their governments and societies that will be needed to maintain the relationship far down the road. Ice cream-induced bonhomie notwithstanding, this was made very clear when the 10-year cooperation program between the Russian Far East and the Chinese Northeast was scrapped at the end of 2018, replaced with a much less ambitious shorter-term agenda for 2018-2024. Xi nevertheless stated that the “years of interregional cooperation were a success” in his comments to the press after the St. Petersburg Economic Forum in June 2019. Putin, at the same press conference, noted that the two countries were developing cooperation between non-contiguous regions, such as China’s coastal regions and Russia’s Northwest, a further sign that Sino-Russian relations would continue to be managed from above, rather than developed through cross-border economic integration.

Elizabeth Wishnick is Professor of Political Science at Montclair State University and Senior Research Scholar at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University.

[PDF]

Homepage image credit.

Memo #: 620

Series: 2