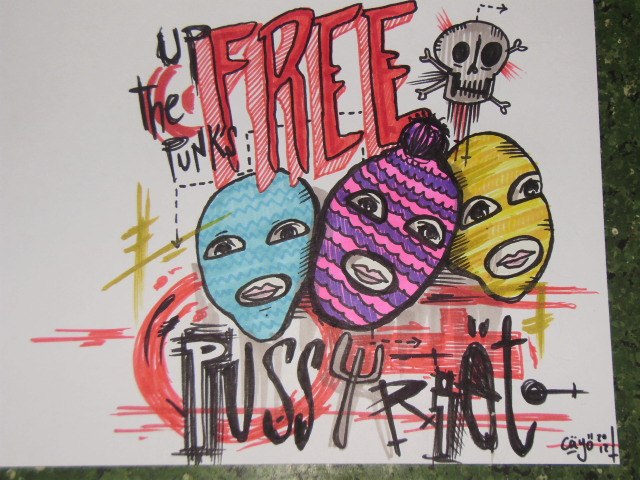

The Pussy Riot affair comes in different versions: it can be told as a legal case, a moral storyline, or a political gesture. It is this mixture of different genres that makes it so hard to reach a relative consensus in covering the story. But drawing lines between different logics and roles is important when analyzing the Pussy Riot incident.

For most observers it is evident that the Pussy Riot trial is a political one, but it was the state that decided to tackle it as a criminal offense. The Kremlin, on the one hand, wanted to depoliticize the group’s actions and frame it as a legal issue. Yet, on the other hand, it is the legal arguments that appear to be the weakest element in the Kremlin’s strategy. Through this route, the case actually demonstrated the deficiency of Russia’s legal system and the system’s dependence on the will of the executive authorities.

According to former Pussy Riot lawyer Nikolay Polozov, the group’s actions should have been seen as an administrative violation and not a crime. (The Russian Administrative Code, however, does contain a clause on “offending religious feelings” that could have been applied.) Moreover, the group’s lawyers documented numerous procedural violations during the court sessions: they were not allowed to make legitimate appeals to the court; call on witnesses (like Alexey Navalny); communicate confidentially with their clients; and the detention regime was like torture because the accused were woken at 6 a.m. and allowed to go to bed only after 1 a.m.

On August 17, 2012, the three members were convicted of "hooliganism motivated by religious hatred." (Since then, one has been set free on probation while the other two are in prison camps.) The point of the matter is that they performed a political act of protest against the regime, not against the Church. They were demonstrating against the unconstitutional “merging” of the Russian Orthodox Church with the state.

Metropolitan Kirill has publicly disallowed Orthodox believers to participate in street protests claiming that the Church is beyond politics. But in the meantime, the Orthodox Church has clearly politicized itself by always defending the Kremlin.

In denying the political background of the Pussy Riot affair, the state not only criminalized the performance, but turned the action into a clerical (theological) matter, thus making the Orthodox Church defend Putin’s regime.

The Kremlin, from the outset, felt that purely legal arguments would be insufficient, so they manipulated information to sway the public against the group. This strategy might have its own rationale: the Kremlin tried to recreate a pro-Putin majority grounded in conservative and parochial worldviews.

This, as Polozov and others have indicated, is a Kremlin strategy based on medieval norms—historical monuments rather than regulators of contemporary religious life.

At the intersection of the legal and clerical debate, there is an important question. How exceptional is the Church from the legal point of view? In Polozov’s words, the Cathedral where the actions took place is a public space: only 7 per cent of the Cathedral is technically leased by the Russian Orthodox Church, the rest belongs to the Moscow city government.

A panel discussion on the case by the German–Russian Association of Lawyers in Berlin discussed all of these issues and more. They said that the case highlights the lack of rule of law in Russia and it only further alienates Russia from Europe. Russia seems to be increasingly perceived as a retrograde state in Europe. At that discussion, Fr. Andre Sikoyev of the Russian Orthodox Church abroad attempted to defend the accusations against the young ladies, but he was met with vociferous irritation by the audience.

The Pussy Riot story is far from over. Both sides are preparing for new moves. Should the court decide that the performance video itself is “extremist,” there could soon be a second trial against the punk group. Meanwhile, the defendants are seeking justice outside of Russia and have filed a complaint with the European Court on Human Rights.

Andrey Makarychev is a Guest Professor at the Free University of Berlin, blogging for PONARS Eurasia on the Russia-EU neighborhood.