(PONARS Eurasia Commentary) The “curse” of the Soviet legacy continues to permeate post-Soviet nations in many ways. For instance, the Russian leadership actively draws on the Soviet past to justify its aggression against Ukraine. It is sufficient to recall President Vladimir Putin’s essay “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’” claiming that Russia and Ukraine were really one country and that modern Ukraine was historically a Russian territory.

Most recently, in December 2022, it was the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Soviet Union. This formation has long disappeared from the world map, but many in Russia still consider this date very significant. True, there were no official celebrations of the centennial in Moscow, but the initiative came from below, from the regions. The Moscow region launched a cultural and historical project, “One hundred years of the USSR. Best Practices.” In many regions, universities organized special round tables by students and professors, and libraries organized special book exhibitions. The Russian Historical Society held an international scientific conference, “One hundred years of the formation of the USSR: new views and new approaches.” It seems that today in Russia, remembering and celebrating (albeit modestly) this date is a good tone and the right signal to the higher authorities.

What comes to mind first when thinking of the USSR? Its territorial size. A gigantic territorial structure, occupying one-sixth of the world’s land mass (an object of enduring pride for Soviet and Russian schoolchildren). But how does the Soviet legacy of center-regional relations work now? In the Soviet Union, the stability of the center-regional relations crucially depended on the severe limitations of political liberties and the absolute dominance of Moscow. However, dominance can be realized in practice in different ways. The Soviet Union practiced a rather unusual vertical hierarchy of dominance and control. At the top, there were the central authorities. The center (Moscow) extracted and redistributed resources from all parts of the country, including Russia. Interestingly, Moscow did not extract economic resources to enrich Russia (RSFSF) or ethnic Russians. On the contrary, in the Soviet Union, the redistribution decisions favored, at least in per capita terms, the non-Russian republics.

Though the living standards and opportunities for career advances in the national capitals (Moscow and St. Petersburg) were, on average higher than in most parts of the USSR, there were residency requirement limitations to restrict the inflow of population to the capitals. At the second level, there were authorities of 15 Soviet Republics acting like imperial centers when dealing with their subordinated subjects—the regions and local governments. The living standards in the capital cities of all 15 republics were comparable with those in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The third level—the regional centers and large cities exercised dominance further down the Soviet “vertical of power.”

The demise of the Soviet Union destroyed the highest layer of the hierarchy. Yet the rest of the formal institutional system remained in place, though, importantly, now without the centralized and hierarchical Communist Party. Bureaucracy, norms, political culture, and expectations of dominance and control remained in place. In that sense, the principles of state organization in “Russian” and other post-Soviet spaces have survived well beyond 1991. Another important element of the Soviet legacy was the tradition of combining bureaucratic hierarchies in center-regional relations with informal practices. In practice, the relations between Moscow, republics, and local governments often followed informal rules and practices. The collapse of the Soviet Union with the destruction of formal institutions (rules) and hierarchies made informal institutions even more important.

The history of the Soviet Union (and the Russian Empire) clearly demonstrated that while conquest and dominance worked, any attempt at liberalization was dangerous for territorial stability. There was no lasting respect for the federal constitutional provisions—all federal compromises were rather temporary, and the central authority was never restricted in practice by the federal principles. Moscow repeatedly changed the list and status of the Union and autonomous republics, their composition, and representation both in the formal institutions as well as in the communist party ruling bodies. Soviet-style Federalism was just another instrument of control and dominance by the Center over the peripheries.

In many respects, the model of the center-regional relations in territorially large post-Soviet countries like Russia and Kazakhstan came to resemble the Soviet model. However, it is important to emphasize that having preserved a great deal of the Soviet legacy Russia (like other post-Soviet countries) has failed to restore the most important mechanism for maintaining territorial stability of the Soviet period: the centralized and hierarchical single-party regime. The rule of the single party (the Communist Party) was the most important instrument of control and dominance and the “cement” for the whole political system. Without centralized and hierarchical control of the single-party regime, the formal constitutional mechanisms of the Soviet Union institutions could not last.

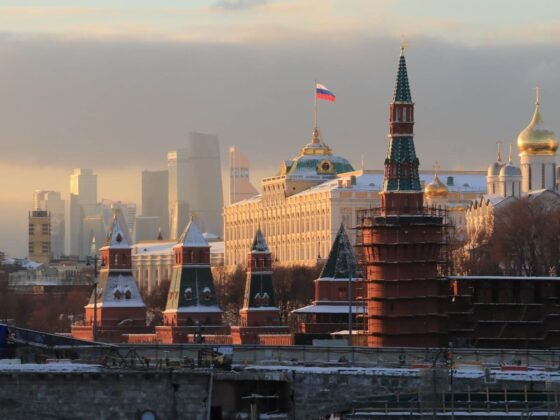

In Russia, the Kremlin’s attempt to turn United Russia into the likeness of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party has obviously failed (just as the Nur Otan party failed in Kazakhstan). A personalistic regime has been established in Russia. So, the practices of the Soviet legacy coexist not with a single party, but with a personalistic regime. This combination makes the system of center-regional relations fragile and unstable in the event of a significant drop in the person’s (the president’s) popularity level.

Irina Busygina is Visiting Scholar at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University.

Mikhail Filippov is Professor of Political Science at Binghamton University, State University of New York.