Successful regime change demands that Russians build a clear program of transitional justice (TJ), defined as a set of policies for dealing with former authoritarian elites and their collaborators. The goals behind a TJ program would be to solidify democratic representation, fight corruption, and promote societal reconciliation. In addition, an effective program would construct a roadmap for identifying the guilty among the Putin-era elite, define a set of TJ mechanisms, and prescribe how they should be implemented. With hindsight, the lack of TJ policies related to personnel after the collapse of the Soviet Union, such as purges and lustration, hindered Russia’s democratic consolidation by allowing for the continuation in power of former elite cadres, especially the security services. The international community should work closely with Russian scholars, opposition organizations, human rights activists, journalists, and lawyers to ensure that Putin loyalists do not escape retribution.

Russian voices are critical to framing TJ policies. This memo uses data from 216 semi-structured in-depth interviews with Russian citizens who fled the country after February 24, 2022, the day Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The results show that most respondents believe that some form of TJ must be implemented with regard to the Putin regime’s elites. There is widespread agreement that a lack of justice—including selective law enforcement, politicized court decisions, and impunity of state officials for human rights violations—is the key problem in Russia. En masse, informants argue for trials of war criminals. In addition, many suggest that TJ mechanisms such as trials, purges, or lustration, should target high-profile officials, the security apparatus, and propagandists, but not rank-and-file regime servants. The goal of the TJ approach should be to create a healthy society that respects human rights and a democratic political system.

Russian State and Wartime Migrants

Contemporary Russia is a personalized autocracy, governed not by formal “rules of the game” but by informal deals among regime insiders and the personal desires of Vladimir Putin. Over time, Russia has become increasingly dependent on repression and polarizing propaganda narratives as key tools of domestic politics. Unjust court verdicts against political opposition figures, raids on activists’ homes, surveillance, threats, and the use of force against dissenting citizens have become the norm. In launching a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the regime demonstrated its outright disregard for the value of human life and the established world order. The authorities have left no room for Russia to break with its authoritarian legacy without fundamental political and personnel changes.

To identify debates about TJ in post-war Russia, Indiana University and the OutRush team asked these questions to Russian wartime migrants as part of the “Building a Commons in the Russian Diaspora” research project. Informants for the project were recruited through a panel survey of Russian migrants overseen by the OutRush team and through snowball sampling. Irrespective of the method by which they were recruited, all respondents had experience of living in one of the following six countries: Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, and Turkey.[1]

The interview project provides a valuable source of information about the direction of political change in Russia and future policy toward regime elites and their collaborators. The views of Russian wartime migrants are highly relevant because they provide insider knowledge of the political, economic, and social systems in Russia. On average, our informants represent the most educated and politicized segment of Russian society. Many of them fled the country because they disagreed with the war on moral grounds but were unable to protest back home due to escalating repression. Many further expressed a desire to return home and become politically active in the future, helping to rebuild Russia into a responsible democratic state. Some migrants reported having themselves been victims of human rights violations. Thus, wartime migrants have strong opinions on issues such as political changes and TJ. Their testimonies complement existing research accounts and can be taken as a point of departure for planning steps to be taken following the transition.

Political Changes and the Need for Justice

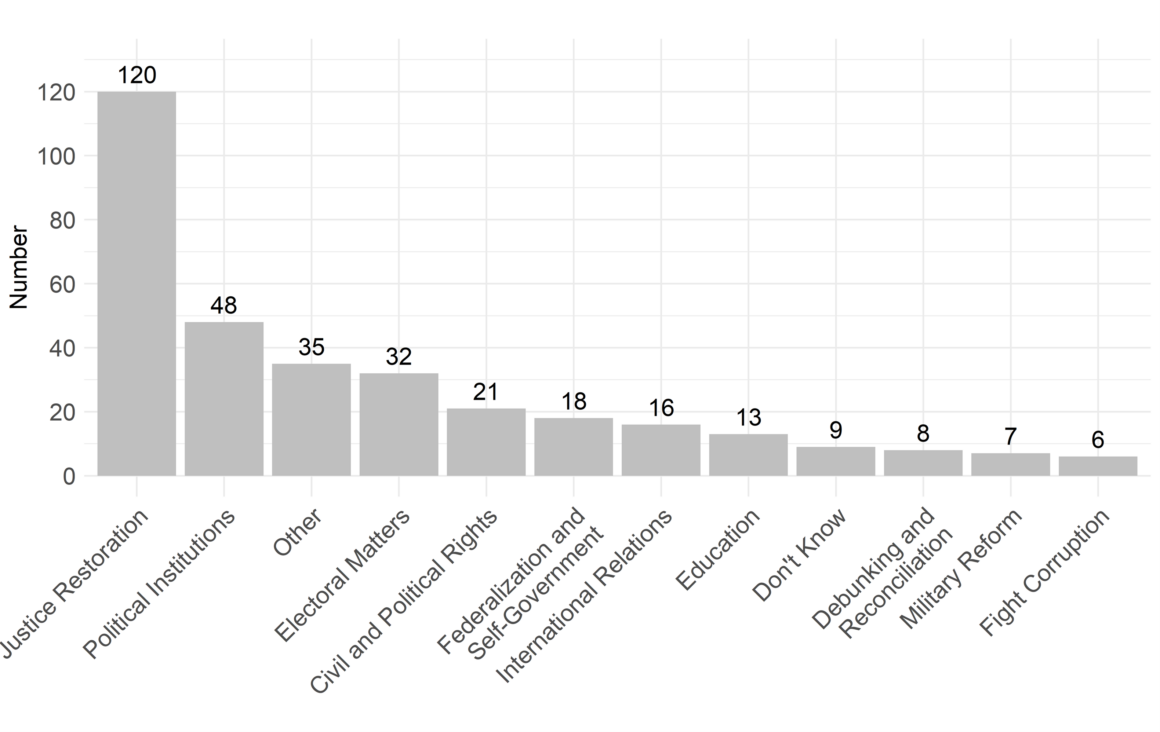

During their interviews, 124 of our respondents were asked: “Imagine that the conditions for your return to Russia have been met, and by returning you could influence what is going on in the country. What would you suggest doing first?” As a rule, interviewers asked this question of respondents who wanted to return to Russia in the future. Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses. The horizontal axis displays broad categories of desired changes. The vertical axis reflects the number of times each category was mentioned.

Figure 1. Migrants’ Proposed Changes in Post-Authoritarian Russia

Note: Each informant could discuss as many changes as s/he wanted; aggregated categories are shown.

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of interviews.

A lack of justice was the issue most frequently cited by respondents, followed by the design of impartial political institutions, conducting free elections, and respect for basic civil and political rights. Speaking of justice restoration, people mentioned judicial, legal, and police reforms; the release of political prisoners; and the need to hold accountable those responsible for both running the war in Ukraine and human rights abuses in Russia. More specifically, one in five respondents answered this open-ended question by expressing support for some form of punishment against those who worked for the Putin regime.

All informants, except those who had already mentioned some form of retribution against Putin loyalists in response to the above question, were subsequently asked: “In your opinion, does Russia need a special policy for people who collaborated with or held public office under Vladimir Putin’s regime? If so, what should it be?” The vast majority of informants argued for some TJ options to be implemented. Only eight respondents said that there would be no need for such a policy, while 16 respondents were unsure whether or not such a policy would be necessary.

TJ for War Criminals

When addressing the targets of TJ, informants frequently mentioned those people involved in running the war and in committing atrocities against civilians, such as the Bucha massacre. They considered these individuals to be war criminals. While most informants did not identify individual war criminals, some mentioned the Security Council, Putin, his inner circle, or the Wagner Group. The following views are representative of respondents’ perspectives:

… in my opinion, some kind of tribunals are needed for the high-ranking officials and for the war criminals—that is, [for those] who gave the orders, [for those] who killed civilians. (Female, Serbia, April 12, 2023)

… I believe that war criminals should be tried. And they should be tried first in Russia. And then, secondly, if the international community convinces [Russian society] that they… need to be tried somewhere else, then it is necessary to extradite them and prosecute them there. (Male, Serbia, May 26, 2023)

Well, in my opinion, the decision makers should of course be held responsible for everything that is happening now. And theoretically speaking, and if “the Hague” would ever be possible, all these people must certainly stand before a court. (Female, Georgia, April 6, 2023)

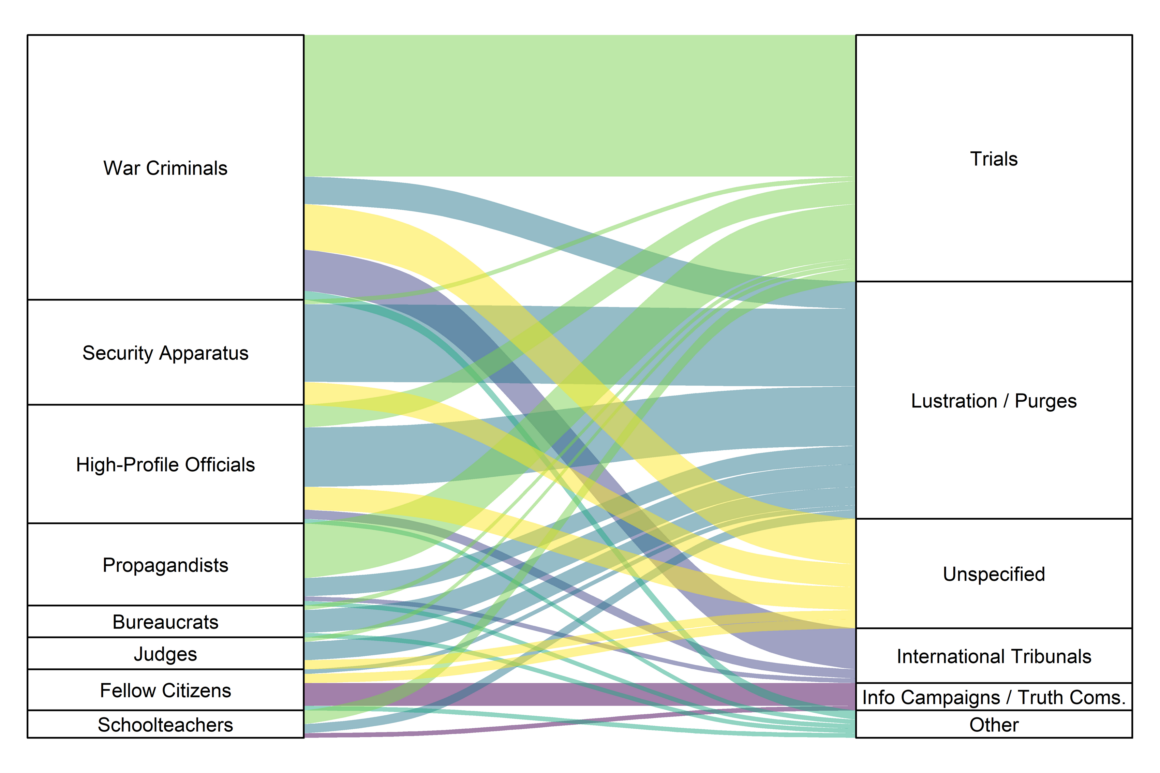

In general, informants agreed that war criminals must be brought to justice. Figure 2 illustrates this by showing associations between the targets of TJ (left axis) and the TJ mechanisms to be used against them (right axis). Typically, respondents did not specify the type of trial they meant, but as a rule they spoke of Russian trials. Some informants also mentioned international tribunals.

Figure 2. The Link between Targets and Specific TJ Mechanisms

Note: Each informant could mention as many targets of TJ and TJ mechanisms to be implemented against them as s/he wished, or none; each mention was counted separately.

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of research.

TJ for High-Profile Officials, Security Apparatus, and Propagandists

Many respondents also suggested that TJ must target high-profile civil officials, the security apparatus, and propagandists. With regard to these groups, informants stressed the need for trials of propagandists, as well as for lustration and purges of both the security apparatus and high-profile civil officials (see Figure 2). Despite the analytical difference between lustration (the vetting of candidates for public office for ties to the authoritarian security apparatus) and purges (the removal from office or prohibition of holding office of known collaborators), in many cases respondents did not draw a precise distinction between them. Perspectives similar to the following were shared by several respondents:

People who occupied high positions and made monstrous decisions should probably be… well, not probably, they certainly must be judged according to the law. Propagandists included. (Female, Uzbekistan, July 4, 2023)

… High-profile officials must face lustration, and since most of them are war criminals, they also must face a genuine trial. (Female, Georgia, May 24, 2023)

When it came to the Federal Security Service (FSB), respondents clearly advocated for the organ’s dissolution. A representative example of this sentiment came from a middle-aged male respondent:

The FSB must be totally dissolved, totally dissolved, and a full investigation into all the crimes it has committed must be carried out—and there are many, because the FSB’s activities are inherently criminal… (Male, Germany, June 5, 2023)

Interestingly, Russian migrants’ perspectives about transitional justice parallel those expressed in South Africa several decades ago. In the latter case, political leaders and members of the government’s security apparatus were seen by many South Africans as the main perpetrators of the apartheid regime, who should not escape punishment. Retribution against them was considered an important step in the reconciliation process.

TJ for Rank-and-File Regime Servants

Some wartime migrants argued that TJ should target rank-and-file regime servants, such as the bureaucracy or even schoolteachers. Most informants, however, rejected this idea—not because they were tolerant of regime support, but as a trade-off for governability and to avoid a possible bureaucratic shutdown.

I think people have to be separated. Those who had real responsibility for making some decisions, [who] committed war crimes—they must be prosecuted. But it seems to me that if a person simply worked for the state as a low-level bureaucrat—well, I’m not sure that a special policy, some kind of punishment or anything like that is needed. (Female, Serbia, April 12, 2023)

I’m not a big fan of all these bureaucrats, careerists and so on. But unfortunately, somebody has to do a lot of all kinds of work. (Male, Serbia, May 26, 2023)

By and large, Russian wartime migrants’ perceptions of TJ align with recent scholarly accounts showing that while leadership purges are necessary in post-authoritarian societies to hold high-profile supporters of the ancien régime accountable and satisfy popular demands for justice, more widespread and thorough purges can undermine governability and the way the state is run.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of the transition from authoritarianism, a crucial task will be to rebuild Russian justice institutions from scratch. Those who participated in running the aggressive war against Ukraine and committed human rights violations within Russia must also be held accountable. TJ is especially important, as allowing former authoritarian elites to disperse across state institutions undermines the quality of democracy, opens the door for political corruption, and decreases trust in public institutions.

Both the international community and the Russian opposition must take seriously the idea of holding war criminals, high-profile officials, the security apparatus, and propagandists accountable for their actions at home and abroad. The international community should consider mechanisms to limit these actors’ ability to escape retribution and should take steps to invest in investigations of Russia’s atrocities in Ukraine.

The Russian opposition must acknowledge that at least among Russian wartime migrants, there is a strong demand for justice back home. The question of holding supporters of the Putin regime accountable should not be avoided. At the same time, both to secure the support of its core audience and to avoid provoking a backlash, the Russian opposition should not call for thorough purges. Instead, in addition to the trials of war criminals and propagandists, leadership purges, and the dissolution of such entities as the FSB, the opposition should focus on setting up special bodies that will reveal, publicize, and disseminate the facts about the atrocities and human rights abuses committed by the Putin regime, as well as on opening the archives and uncovering those who secretly collaborated with it.

Mikhail Turchenko is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Indiana University’s Ostrom Workshop. He studies electoral engineering, party system fragmentation, voting in authoritarian elections, transitional justice, and transnational repression. His work has appeared in Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Demokratizatsiya, Europe-Asia Studies, Post-Soviet Affairs, Problems of Post-Communism, and Russian Politics.

[1] This comparative research design allowed for an exploration of the impact of host-country context on migrants’ opinions, a factor not central to this memo.