PONARS scholars and experts discuss the unprecedented presence of signs related to Russia at Saturday’s Women’s March throughout the United States and the world. While perhaps not surprising given the role played by Russia in the recent U.S. election, what effect is sustained public attention on Putin’s relationship with Trump, and Russia’s role in U.S. politics generally, likely to have on U.S.-Russian relations during the Trump administration? Does this present new challenges? Opportunities?

Mark Kramer (Harvard University) — The marches in Washington, DC, New York City, Boston, and numerous other U.S. cities on January 21, the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration as president, featured a medley of leftwing activists and slogans and included speakers whose presence was bound to alienate anyone who was not already committed to leftwing causes. The protest organizers seemed to have little interest in trying to reach out to those beyond the left. In that respect, the “movement” the protesters claimed to be fashioning will likely make scant headway.

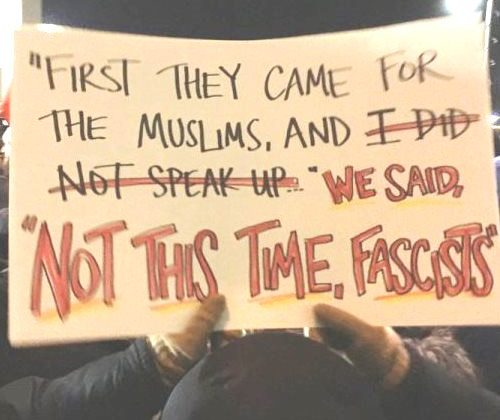

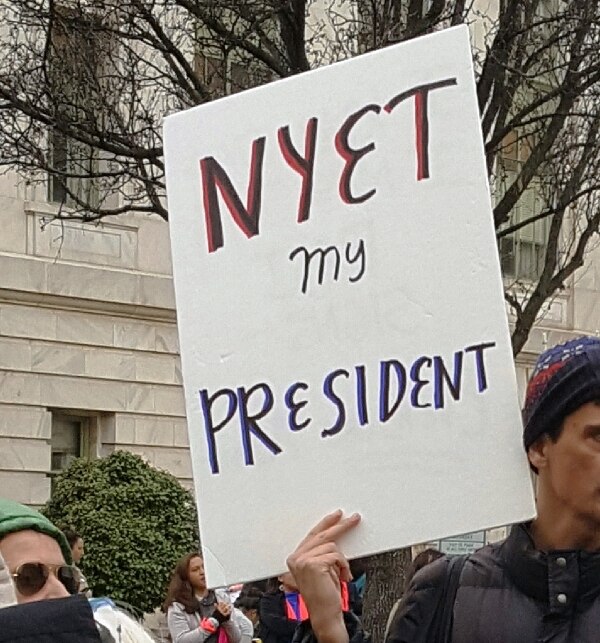

Even so, there was one interesting aspect of the marches, namely the way Russia was depicted. In light of recent allegations that the Russian intelligence services used cyberwarfare and other covert and overt means of influence to try to help Donald Trump get elected, many of the protesters embraced those allegations with gusto. Posters and slogans featured Trump as little more than a sinister stooge of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Such depictions are of course influenced by the larger pop culture. The widely watched satire-comedy show Saturday Night Live has been depicting Trump as a Russian-backed stooge for the past several weeks.

Most of the time over the past fifty years, leftwing activists have been deeply suspicious of and hostile to U.S. intelligence agencies — after the Bay of Pigs in the 1960s, during the Church hearings in the 1970s, during debates over United States aid to anti-Communist insurgents in Nicaragua in the 1980s, and after misjudgments by U.S. intelligence agencies about the presence of weapons of mass destruction in the lead-up to the 2003 Iraq war — but now those same activists have hailed the intelligence agencies as truth-tellers. In some sense this might be seen as a healthy development, but more likely it is driven solely by political expediency. To the extent that the intelligence agencies’ findings raise troubling questions about Trump — and they certainly do — the activists will be happy to back the agencies. (Whether that backing will extend to other issues is doubtful, however.)

That Trump’s unusual fondness for Putin over the past year has become a rallying point for his opponents is an interesting and ironic twist. Just a few years ago, after Putin announced the annexation of Crimea, Trump repeatedly spoke harshly about Russia and explicitly endorsed Mitt Romney’s characterization of Russia during the 2012 presidential campaign as the “No. 1 geopolitical foe” of the United States. Indeed, Trump went further than Romney ever did, describing Russia as a “danger” and a “major threat.” On 24 March 2014, for example, Trump called for a tough stance against Russia and sanctions that would “do economic damage”:

Well, Mitt was right, and he was also right when he mentioned in one of the debates about Russia, and he said, Russia’s our biggest problem, and Russia is, you know, really something. He said it’s a hell of a problem, and everybody laughed at him, including certain media, by the way. They laughed. It turned out that he’s absolutely right. You look at what Russia’s doing with Iran, how they controlled the situation, and Syria, and virtually every other place that … We were thrown out of every place … To be scoffed at and thrown around the way we’re being thrown around is absolutely unthinkable.

On many other occasions in 2014, Trump made similar comments about Russia, advocating a hard line. Only with the start of the 2016 presidential campaign did he suddenly take a much softer and more indulgent stance toward Putin’s regime. So, the real question is: What changed between March 2014 and Trump’s entry into the 2016 presidential campaign? Both during and after the 2016 campaign, Trump seemed unusually eager to antagonize key countries, including adversaries like China and Iran as well as allies like Japan and Germany. Yet, both during and after the campaign, he consistently expressed warm feelings toward Russia and Putin. What accounts for this discrepancy? The explanation is not yet publicly known — and may not be known for a long while — but suspicions are bound to persist unless a full investigation is pursued.

Whatever the outcome of such an investigation, one consequence of the furor over Trump’s questionable fondness for the Putin regime in 2016 is that his leeway now for far-reaching changes in U.S. policy toward Russia is apt to be circumscribed. If Richard Nixon had consistently expressed warm feelings about Communist China during the 1968 presidential campaign, his breakthrough with China in the early 1970s might not have been feasible. Trump faces that same sort of problem now — the opposite of the Nixon-to-China syndrome. Any steps that Trump takes now to make significant improvements in ties with Russia, whether the lifting of sanctions or recognition of Russian’s annexation of Crimea, will be viewed with suspicion, and rightly so. In these cases, it will be not just leftwing protesters but also foreign policy hardliners like John McCain and Lindsey Graham who will want to know whether Trump is acting on the basis of ulterior motivations. Hence, if someone in the Kremlin did want to help Trump in 2016, that intervention seems to have been counterproductive.

Regina Smyth (Indiana University) — Given the lack of outcry and relatively tepid concern in opinion polls regarding allegations of Russian influence in U.S. elections, the number of Russia related signs at the Women’s March in Washington, DC, was unexpected. While the majority of posters drew heavily on broad themes related to women’s health, autonomy, and rights, there were a wide range of signs centered on climate change (mother earth), voting rights, healthcare and equal protections for the LGBTQ community. Russia-related signs were in the minority of the themes represented in protest art but they were still significant. The signs and posters were clever and often beautifully executed with impressive art. They were also constructed by people with some knowledge of Russia, the US presidential campaign, and the issues at hand. There were a few Pussy Riot balaklava’s, many depictions of shirtless President Putin, and signs that used historical themes and Stalinist-style posters with photo-shopped faces of Trump and Putin. There was also a great deal of Soviet-era Cold War imagery.

The signs linking Russia, Putin and Trump invoked existing language and memes that were often bawdy and hilarious. The playfulness of the messages raised the question as to whether the Russia/Putin connection was simply fodder for good puns and comedy or reflected deep concerns of the Trump opposition. I would argue that this art carried a clear message of concern. The signs introduced three broad arguments. The first argument framed the issue in terms of Mr. Trump’s close relationship to Mr. Putin. These placards included art of the two Presidents together, lists of Presidential tasks that included phoning Mr. Putin or visiting Moscow, and spending time together. A second group reflected concerns about Russian interference in U.S. elections. These placards depicted Mr. Trump as a puppet (invoking HRC’s charge in the third presidential debate) or a stooge. Others targeted Mr. Putin with strong images and the words “Not My President,” or stated that Mr. Putin had put Mr. Trump in office as in, “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Tsar, Putin Put You Where You Are.”

Many of these posters were also bawdy, invoking the salacious details of the Steele briefings in puns and metaphors. The final group of posters focused on the perceived autocratic tendencies of both leaders. This last group of signs was much smaller than the other two. Still, as a whole the prevalence of these themes showed that President Trump’s ties to Russian are increasingly salient as a point of concern and a mechanism to mobilize opposition.

There were also some signs in Russian and translated in English. At one point late in the day, a group of activists misunderstood the intent of the sign with the words “Demagogue, Fascist, Troll, Predator, Fraudster. The Truth Will Defeat You,” written in Russian. They started chanting “USA” and “This is America.” The author turned the sign around showing the translation and the crowd erupted into cheers. There was also a Russian language “Pussy Riot” placard with art depicting the “Pussy Grabs Back” meme and referencing Mr. Trumps remarks on the released video footage with Billy Bush. In conversations on the street, in the metro and the airport, participants noted the gap between current polls and the messages of the posters related to Russia at the March. They also stressed the need to continue Congressional investigations into linkages between the campaign team and Cabinet members to Russia. These pressures may bolster Congressional resolve. Although not a central goal of the March, it reinforced the growing sense that voters should be pressing their representatives to continue investigations now underway.

The depiction of U.S.-Russian relations on the street could provide a serious obstacle to improved relations with the Trump administration. The crowds across the United States were large and diverse and are likely to spur Congressional concern about alliances with the Trump administration over foreign policy, especially in light of new reports of ongoing efforts by the intelligence services. The focus on Mr. Putin as the problem and the depiction of him on the posters at the march have the danger of reigniting personalism that impedes comprehensive policy toward Russia. Increasing the salience of Russia among the Trump opposition could undermine any hope of a better relationship. Mr. Trump will find it much easier to bait Mr. Putin than to address the other serious concerns of March participants: funding for Planned Parenthood, the protection of reproductive rights, support for LGBTQ rights, and voting rights. This is particularly true if his focus is on domestic policy over any international concerns. On the other hand, the focus on Russia raises the potential for a sustained and serious conversation about what a good relationship with Russia might look like rather than defining a good relationship as a policy goal.

Marlene Laruelle (George Washington University) — The use of Russia-related signs during the Women’s March offers several insights on U.S. popular political culture and the role of foreign policy topics in it. First, the March confirmed how a large part of the population (especially its activists) receives information through social media and is shaped by it. The majority of Russia-related flyers, slogans and memes were all coming from the social media culture and had previously been circulated on Facebook and other similar media. The March just put in the street symbols and memes that had already been online for several weeks. They combine the ultra-personalization of Putin and Trump, gendered clichés (as discussed below by Valerie Sperling), and a reductio ad Hitlerum, or more generally an effort to associate political opponents with “fascism.” “Traditional” media and professional journalists are now only one element among many others in a kaleidoscope of information flows, and they sometimes tend to just follow and reproduce trends that are already ‘viral’ on social media, as we saw in the hyper-inflated and largely evidence-empty debate about Russia’s alleged meddling in U.S. elections.

Second, it is rare for a foreign policy topic to enter broad popular political culture, which in the United States is, as everywhere else in the world, traditionally mostly focused on domestic and socioeconomic issues. The elevation of Russia to the role of America’s new enemy and the antithesis of what the Women’s March public wants for the United States gives us insights into the enduring prevalence of old Cold War schemas. The “Red Scare” of the 1950s was easily revived and updated: It shifted from hidden communists trying to influence society and infiltrate the federal government to conservative white men and blue-collar workers — those identified as Trump’s electorate — trying to stop the “liberals” and “progressives.” By giving Russia the symbolic role of embodying the political divide of American society, the Women’s March indirectly contributed to a simplistic black-and-white interpretation of the struggle over values and handed their detested Putin’s regime one of its easiest successes.

Maria Omelicheva (University of Kansas) — My thinking on the impact of public contention over Trump’s “cozy” relations with Putin on the future of U.S. foreign policy toward Russia under the Trump administration draws on the studies of public opinion and foreign policy. Aptly summarized by a distinguished scholar of political communication, W. Lance Bennett, the relationship between public opinion and policymaking in the United States is like a three-way street: American policy makers can choose to ignore public opinion, respond to “the will of the people,” or manipulate it to ensure that the public supports (or ignores) policies pursued by public officials. While the probability of the US administration choosing one or another route is still a debatable question, President Trump is likely to ignore the protesters’ dismay with his downplaying of Russia’s role in US politics. In the end, the protesters are not the president’s support base and Trump is not regarded as “their president.”

The impact of Women’s Marches on Trump supporters will be more intriguing. While Trump’s followers are a rather diverse group, they share at least two things in common: They have been undeterred by the president’s proclivity for intolerance, scapegoating, and sexism, and some share Trump’s values and policy preferences. The goal of the Women’s Marches was to send a bold message to President Trump that these values and this rhetoric that exclude, divide, insult, demonize, and threaten has no place in the American society. By bringing in Putin’s Russia to the mix of concerns regarding the incoming Trump’s administration, the protesters, inadvertently, might have elevated the status of Russia in U.S. public opinion. In end, the old adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” has found some support in psychology. Consistency is an important principle of information processing and opinion formulation in humans. By disagreeing on some of the key issues raised by the demonstrators, some Trump supporters will move toward disagreeing with the protesters’ stance on Trump and Putin. The resulting shift in the opinion of some Trump’s supporters on Russia will be in the direction of increased support for the Trump administration’s foreign policy.

Valerie Sperling (Clark University) — One attention-grabbing trope among the signs displayed at the Women’s Marches on January 21 was the use of homophobia and gender-normative masculinity to express anti-Trump views. Some of these signs — harkening back to Marco Rubio’s comment intended to undermine Trump during the Republican Primary — emphasized Trump’s “small hands.” This unsubtle symbolic means to suggest that Trump’s genitalia were on the petite and therefore insufficiently manly side reflects a common technique by which political opponents try to undermine each other’s legitimacy by wielding normative masculinity as a weapon. While “Keep your tiny hands off our rights” (see the photo from the Boston March) expresses a political position about the need for women’s rights to be upheld, it also reinforces the idea that one of the things making Trump an undesirable political leader is a certain deficit in the masculinity department.

Trump’s relationship to Vladimir Putin has similarly been used to impugn Trump’s credibility as a male politician via facetious suggestions that he is Putin’s submissive male lover. This was visible on a sign in DC reading “My Pooty Call” illustrated with Trump and Putin in bed together with red hearts floating around, and a sign spotted in Boston that read, “Trump loves Russian Men.” Like the “small hands” signs, these are designed to undermine Trump’s political image by implying in a homophobic way that there is something “wrong” with him. Although these kinds of signs aim to critique both Putin and Trump by linking them together and showing that they may have found common cause in their dictatorial tendencies, such signs express that critique in a homophobic way.

These techniques of playing on homophobia and gender normative masculinity clearly “work” as a way of criticizing male politicians. People understand the message immediately, and also find the slogans or images amusing because of the sexualized content. But these slogans and images also perpetuate patriarchy by reinforcing the idea that men loving men is “bad,” and by suggesting that yet another reason to dislike Trump is that he is insufficiently masculine. In the end, this means of ridiculing Trump (and other male politicians) reinforces the idea that masculinity and femininity are “real” qualities that have to be embodied correctly, rather than being social constructs that serve to confine us all.

Mikhail Alexseev (San Diego State University) — The imagery was clever, incisive, evocative. It tapped into the emotional whirlpools of anger, disbelief, and repulsion of political reality—Donald Trump’s inauguration as president of the United States. Somehow, somewhere, someone in the land of the free voted for a candidate who embraced an aggressive, anti-American foreign autocrat. How could an American president discount democracy or forget the lessons of appeasement that once paved the way to the most devastating global wars in history?

The symbolism clicked: Trump’s campaign slogan superimposed over the flag of the fallen Soviet empire that Putin has been working to resurrect, Obama’s iconic image ominously transposed to Putin. Yes, the protester’s flag cried out: Trump will make the Evil Empire great again. The Empire will strike back. The Era of Hope is over. The Era of Fear is dawning.

Memories flooded in. I was in the heart of Ukraine’s capital, my native city of Kyiv, in the Independence Square — the Maidan — amidst common folks of every ilk who set up protest camps. Barely three weeks had passed since Ukraine’s then president, Viktor Yanukovych, crushed their most cherished hopes. He refused to sign the association agreement with the European Union. Instead he moved to ally Ukraine with and rebuild the country’s political institutions in the image of the resurgent autocratic Russia. As his riot police and hired thugs from the provinces beat up peaceful protesters into a bleeding mess at the onset of the protests, those people of different ilk came to mobilize against the looming threat. It was all in the posters that popped up around Maidan. One stuck in my memory: Putin playing Yanukovych like a string puppet with the caption evoking Putin’s last name with the Russian word for “the road” — Vse putem! (Everything is on the right track!). The “make Russia great again” banner was the San Diego equivalent.

America and Ukraine being a world apart, I felt the underlying phenomenon of evoking Putin in both protests had something important going for it, some vital underlying essence. I call it “geosocietal conflict.” An autocrat uses state power — since autocrats can swiftly command coercive powers of states they rule — to influence government policy or induce a change of government in a democratic state viewed as a geopolitical rival. However, when such desired change happens (as in Yanukovych signing deals with Putin instead of the association agreement with the EU in late 2013 or as in Trump winning the election instead of Hillary Clinton) the society in the target state strikes back.

This creates tension and hardship. It can be fraught with violence. The charred buildings in downtown Kyiv still testify to that. But in the crucible of this type of conflict societies could also grow stronger, along with civic — pre-eminently democratic — values. Public opinion in Ukraine gives us grounds to hope for the better. Reputable mass surveys show a significant and enduring rise of support for common civic national identity among Ukrainians — across regional, ethnic, and linguistic divides — in the run-up to and after the Maidan. Despite the onset of military conflict over Donbas and a plunging economy, support for democratic governance remained strong. Over 80 percent of Ukrainians by December 2014 believed democracy was preferable to authoritarianism under any conditions.

Talking to people who took part in the San Diego March last Saturday left me in no doubt as to the nature of America’s geosocietal response to the Kremlin’s ebullient backing of Trump — regardless of its actual effects on the election outcome. It was pre-eminently, jubilantly democratic — not in the textbook legal sense, but in the visceral emotional sense. People were responding with smiles and laughter and sparks in their eyes. They were reaffirming hope. They wanted the world to see their determination to celebrate more than ever America’s social values they felt Trump’s cozying up to Putin jeopardized the most: diversity, openness, tolerance, compassion, dignity, and optimism.

Photographs were submitted by PONARS Eurasia members, including by Mikhail Alexseev, Regina Smyth, Valerie Sperling, and Joshua Tucker, at Women’s Marches in different cities in the Unites States on January 21, 2017. Contact us for photograph credit information.