Image credit/license

Should it not change the structure of its political institutions, Russia is unlikely to recover from its authoritarian legacy and will remain a persistent threat to the international order. This memo aims to contribute to the discussion about political reforms for postwar and post-Putin Russia by studying Russian citizens who have fled the country since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Data from in-depth interviews collected as part of a project led by Indiana University, with the help of the OutRushresearch team, offers insights into the political preferences of wartime migrants, who represent a distinct segment of Russian society that is antiwar, young, educated, and politically engaged. The study reveals a strong consensus in favor of justice-oriented initiatives, namely the wholesale rebuilding of the court system. Respondents also seek the restoration of basic democratic principles, especially free and fair elections. These preferences regarding political institutions in a transitional period serve as a benchmark for shaping a future reform agenda for Russia.

Setup of the Interview Project

Vladimir Putin’s Russia is a hegemonic authoritarian regime that lacks functioning democratic institutions and is notorious for the absence of the rule of law, along with corruption, inefficiency, and disregard for international norms. There is no prospect of changing this status quo while Putin remains in power and the aggression against Ukraine persists. However, this does not mean there will be no window of opportunity in the long run. It is impossible to predict what Russia’s transition from authoritarian rule will look like. Nonetheless, having a map of reforms means getting done sooner rather than later the essential work toward rebuilding Russia as a responsible actor in international politics and a state accountable to its citizens. The core idea of this memo is to highlight which areas of reform are of high priority and should be pursued in the first place once the opportunity arises.

The memo draws on data from a large-scale interview project conducted by Indiana University in March-December 2023, “Building a Commons in the Russian Diaspora.” In total, 583 semi-structured in-depth interviews were done with Russians who had fled their home country after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Informants for the project were recruited through a panel survey of Russian migrants overseen by the OutRush team and through snowball sampling. Irrespective of the recruitment method, all respondents had experience living in one of the following six countries: Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, and Turkey.

Among other questions, respondents were asked what they would do if they were to return to Russia: “Imagine that the conditions for your return to Russia have been met, and by returning you could influence what is going on in the country. What would you suggest doing first?” Therefore, the interview project provides a valuable source of information about the direction of future political change in Russia, highlighting the views of wartime migrants—mostly young, educated, and politicized individuals—many of whom express a desire to return and help rebuild Russia as a democratic state.

A Snapshot of Reforms Suggested by Wartime Migrants

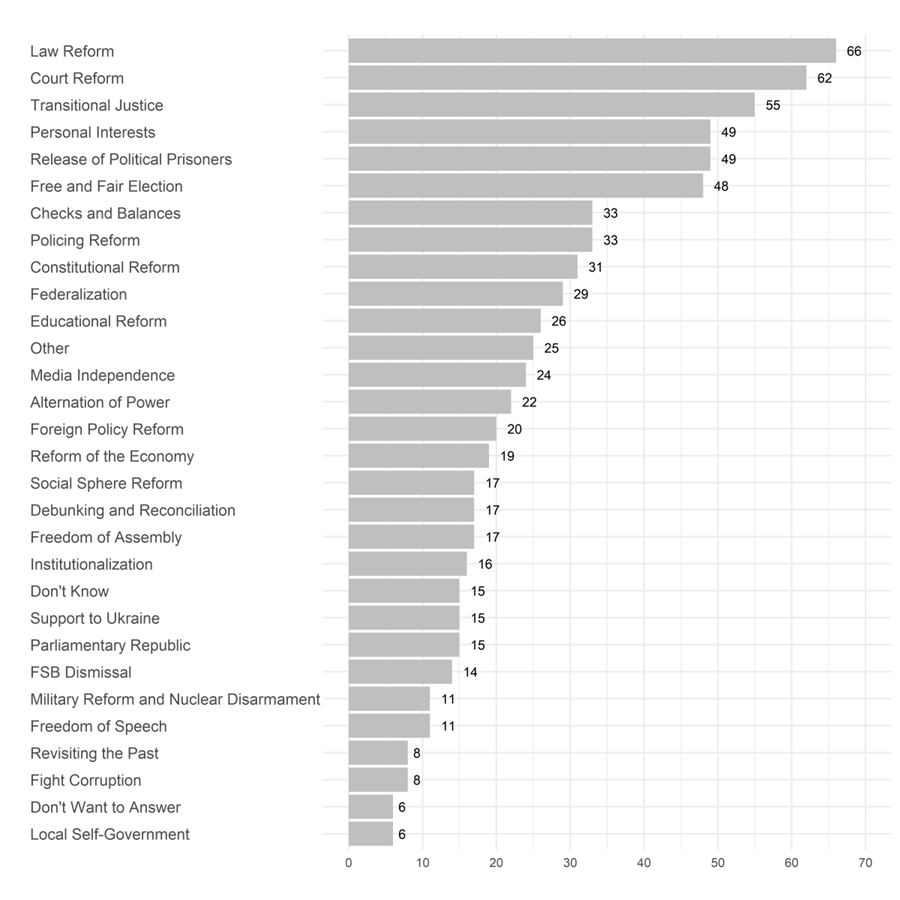

Two hundred and eighty-three respondents were asked about desired changes in Russia. The question was intentionally worded to be open to interpretation. Figure 1 summarizes the responses. In general, people talked about political reforms for a postwar Russia. Some interpreted the question personally—what they would do as private individuals (labeled “personal interests” in the chart). Others advocated helping Ukraine (“support to Ukraine”), a general desire that goes beyond Russia’s internal affairs. A handful of respondents refused to answer (“don’t want to answer”) or expressed confusion (“don’t know”). Finally, several responses were too unique to be grouped into a distinct category (“other”).

In sum, 25 reform areas were discussed. The most common deals with what can be called restoring justice: Legal and court reforms, transitional justice, and releasing political prisoners are the most frequent demands voiced by respondents. The interest in justice-related reforms can be attributed to the fact that, of the 283 respondents, 277 were aware of political repression in Russia, with 71 of them having faced persecution firsthand. As one of the respondents noted while discussing his life in Russia: “Now, the huge problem is that we live in an unjust society” (Male, Serbia, July 14, 2023).

Figure 1. Migrants’ Proposed Changes for Post-Authoritarian Russia

Note: Each informant was free to discuss as many changes as they wished.

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of interviews

As Figure 1 shows, in addition to justice-related reforms, respondents were concerned with the following: reform of law enforcement institutions, political governance structure and institutional design changes, restoration of basic democratic principles, dealing with the legacy of the Putin regime, military and foreign policy reforms, and social and economic development.

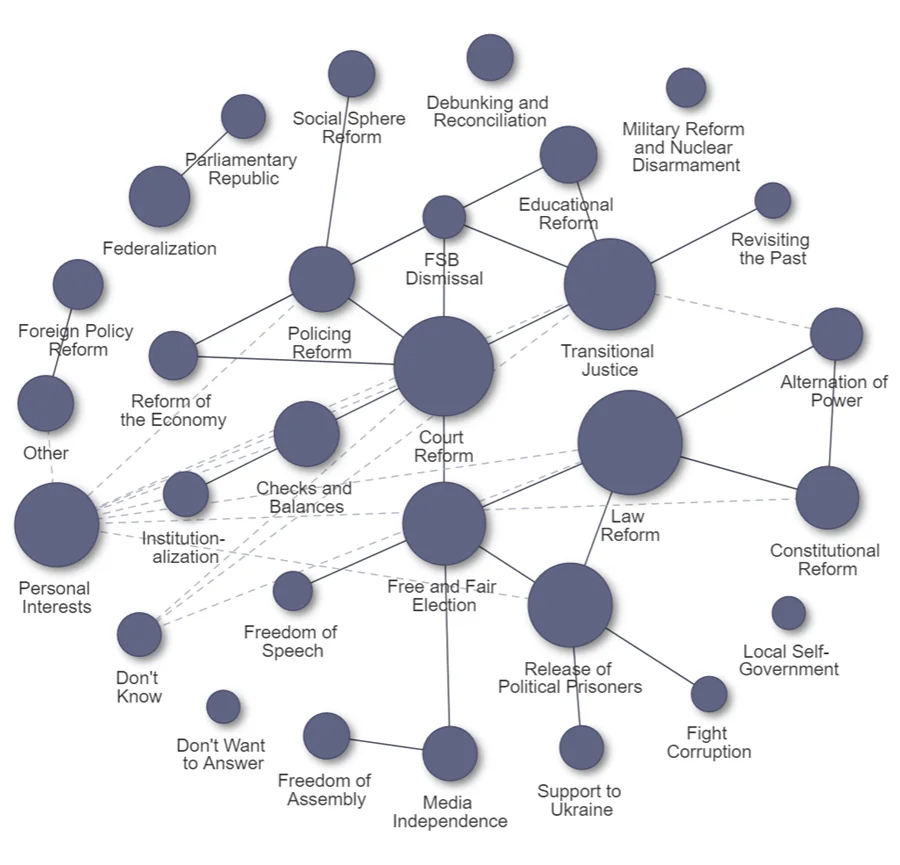

Whereas Figure 1 presents only descriptive information, Figure 2 reveals the connection between different proposed reforms through a co-occurrence network. It helps us to understand which categories are typically mentioned together, which are mentioned alone, and, most importantly, which are at the heart of respondents’ answers regarding the direction of postwar and post-Putin reforms. In the chart, solid lines indicate links that occur together at a higher rate than we would expect by chance, and dashed lines show the opposite. The circle size corresponds to each category’s frequency, reflecting the data from Figure 1.

Figure 2. Network of Migrants’ Proposed Changes for Post-Authoritarian Russia

Note: Each informant was free to discuss as many changes as they wished.

Source: Compiled by the author on the basis of interviews

Court Reform

As Figure 2 shows, court reform—the second-most popular category with 62 mentions—occupies the central place in the network. When respondents mentioned it, they usually referred to their desire for transitional justice, free and fair elections, checks and balances, police reform, the reform of the economy, and the elimination of the Federal Security Service (FSB). Court reform is often considered as the essential prerequisite not only for improving the legal system but also for better protecting civil, political, and economic rights. The following quotes illustrate the importance of court reform.

The most important thing is the restoration of the judicial system. Once courts become independent, everything else will be easier to reform. (Male, Georgia, April 25, 2023)

Well, generally speaking, it’s clear that I would suggest changing the entire judicial system because it’s… It’s the axis on which everything depends. If there were a proper judicial system, there would be no corruption, there would be no war, and there would be no Putin right now. (Male, Georgia, March 27, 2023)

[We need] a parliamentary republic, not a presidential one, and the courts, I would say. And, of course, freedom for political prisoners. I mean… yes, [we need a new] political system because, damn it… the economy, IT. Forgive me, but we’ve really screwed up such a country, seriously… Everything else will follow. You know, the fish rots from the head. So, [we need a new] political system, transition to a parliamentary republic, democratization, independence of the courts, and freedom for political prisoners. (Female, Cyprus, April 27, 2023) [We need to reform] the system of political institutions, and the court system… There’s the electoral system reform is needed. Then, of course, there are some economic and social reforms that need to be done. The political system just needs to be created. The judicial system has to be put in order… Oh, by the way, police reform is needed. The police, the whole punishment system, the judicial system—that is the first thing that needs to be addressed. Ah! The military, the military! The security forces… For example, the FSB, I don’t know, just… dissolve it completely and create something completely different in its place. (Female, Georgia, May 8, 2023).Court reform stands at the intersection of respondents’ desire to effect new institutional arrangements, reform law enforcement agencies, and overcome past abuses. It is seen as the key to restoring core democratic principles, to which the desire for free and fair elections is central.

Free and Fair Elections

Whereas court reform is central to justice-related reforms, the desire for free and fair elections is at the heart of migrants’ demands for political rights. Mentioned 48 times, free and fair elections usually come alongside law reform, court reform, the release of political prisoners, media independence, and freedom of speech.

Well, obviously, I’d like to see… a more democratic regime, a functioning electoral system that prevents all kinds of fraud and violations, and independent courts (Female, Germany, May 7, 2023)

I would definitely want to have the right to vote and to vote for something, and to see how it influences things. That would be super important to me in terms of what I could do on my part. (Female, Turkey, July 14, 2023)

Well, of course, I want fair elections, geez… I’m really curious to experience a situation where I choose between different reforms, different programs. It’s an interesting experience. Why do we pretend that it’s not important? It’s really frustrating that such a large political part of our lives, at all levels of government, is disconnected from us. (Male, Georgia, April 22, 2023)

[What’s important is to] release political prisoners and remove the criminal records and all that from people like [Alexei] Navalny, [Ilya] Yashin, and [Alexei] Gorinov. All this, so they have the opportunity to participate in political life in the future. Unblock the media that have been blocked. In general, provide access to information as broadly as possible, give as many people as possible access to diverse information. Reform the police system, apparently. As for elections… the main thing is to ensure equal access for candidates, and then let citizens elect whoever they want, even the devil himself! As long as there’s equal access to equal information, people will figure it out themselves. (Female, Serbia, April 3, 2023)The prevalence of free and fair elections in respondents’ testimonies can be attributed to the fact that, since 2011, electoral fraud has sparked the biggest protests in Russia: the For Fair Elections protest movement of 2011-2012 and the Moscow protests of 2019. Russian elections have long seen numerous forms of malpractice, ranging from a skewed playing field and voter intimidation to outright falsification.

Other Change Proposals

Some categories were by themselves in the network of proposed reforms, as shown in Figure 2. They might have been linked to other proposals had there been more testimonies from respondents. Among these singular categories are debunking disinformation produced by the state propaganda machine, reconciliation, military reform and nuclear disarmament, reform of local self-government, and foreign policy reform. Federalization and a parliamentary republic also form a small cluster outside the network.

The singularity of these proposals does not speak for their irrelevance to the broader reform agenda for a postwar and post-Putin Russia; instead, they show their rather narrow focus.

Conclusion: A Starting Point for Uniting the Disunited Russian Opposition

The findings outlined in this memo show that Russian wartime migrants’ narratives about future political change in Russia can be grouped around a few themes: restoration of justice, reform of law enforcement institutions, political governance structure and institutional design changes, restoration of basic democratic principles, dealing with the legacy of the Putin regime, military and foreign policy reforms, and social and economic development.

The most visible problem in Russian society is a lack of basic justice, a problem that should be addressed first so as to enable other changes. Respondents also express a strong desire for free and fair elections, a key democratic principle.

The results presented here, despite their limitations in terms of generalizability, can be seen as a benchmark for a reform agenda and a starting point for the diverse and disunited forces of the Russian opposition to find common ground.

[1] Mikhail Turchenko is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Indiana University’s Ostrom Workshop. He studies electoral engineering, party system fragmentation, voting in authoritarian elections, transitional justice, and transnational repression. His work has appeared in Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Demokratizatsiya, Europe-Asia Studies, Post-Soviet Affairs, Problems of PostCommunism, and Russian Politics.

Image credit/license