The Baltic Sea region is definitely one of the best examples of region-building in Europe. It is home to such world leaders in innovation as Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Germany and the region has become an attractive international brand. Baltic studies is a popular research field since this is the region where such fashionable concepts as de-bordering, overlapping identities, governance without government, de-securitization, and other similar concepts and policies were either conceived or tested. Some even think that the Baltic Sea region is on its way to acquiring the key component of any successful regional community—its own identity.

Yet is this indeed happening? If we choose to measure the progress of region-building with established identity criteria, we ought to admit that this region is deeply split, with the EU member states on one side and Russia on the other. For example, the EU's Baltic policies have always been ecologically friendly, making the Kremlin's offensive against Greenpeace activists in northern Russia an especially sensitive issue for Baltic and Nordic countries. A Sunday mass in a Helsinki cathedral even included a prayer for the environmental activists who have been accused of piracy by the Russian court.

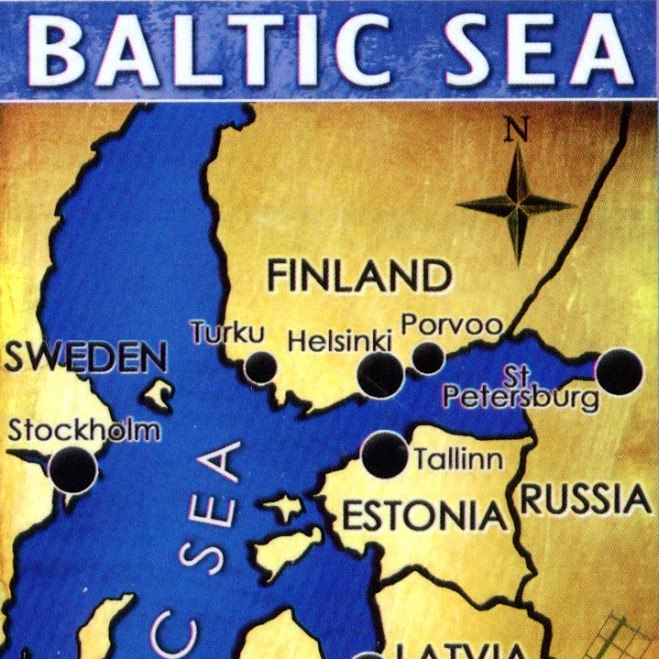

Russia's recent presidency in the Council of Baltic Sea States did not improve the country’s credentials. As a colleague of mine mentioned during an informal exchange of views following the “Frameworks for University Cooperation in the Baltic Sea Region Conference” held in Turku (Finland), Russia was mainly interested in avoiding direct clashes with the West during its presidency (as was also the case during its G20 chairmanship) and, likewise, was also not concerned with promoting any kind of coherent vision for the future.

Of course, there are some islands of interaction between Russia and its Baltic neighbors – the Euro Faculty in Pskov being one example. Yet, as some commentators in Turku assumed, it is hard to measure the degree of success of such projects beyond the formal figures meant for reporting purposes. As the case of Kaliningrad State University shows, on the surface one might see multiple signs of openness to Europe, but in substance, some politically relevant issues are being bracketed off. Based on my personal experience, I can refer, for example, to discussions on Germany's policies toward this enclave, an issue considered too politically sensitive for the Russian officialdom to give a green light to.

One more example of a successful university-based cooperation given at the conference in Turku was the experience of the Stockholm School of Economics in Moscow. However, while figures may be impressive, operating in the Russian educational market is unfortunately possible only under the condition of "keeping close and good ties to the Russian establishment." After all the nice talks about alleged common values, Professor Anders Liljenberg expressed the simple formula for success: "As soon as Putin wants us to stay, we will.” Of course, this sets limitations on the content of academic programs. I asked Professor Liljenberg if it would ever be possible to offer a course on corruption in Russia in Moscow and invite independent experts as guest lecturers to talk about the political economy of mega-events in Russia such as the Sochi Olympics. I received a very telling answer: "Of course we have to be cautious. I myself, for example, started telling my Russian students stories of corruption in Sweden.” At that remark, some people in the audience started giggling ironically.

Without relinquishing the very debates on Russia's engagement with its Baltic partners in educational and academic projects, we have to face what is for many the harsh and unpleasant reality that the Russian educational system is increasingly criticized within the country itself for its gross mismanagement, declining professional standards (with mass-scale plagiarism as the best evidence for this), widespread corruption, and huge gaps in salaries between university bosses and ordinary staff. The creeping politicization of education, the growth of clerical trends, and brain drain add more skepticism to the overall picture.

Some colleagues from St. Petersburg and Pskov suggested that such a scenario is much too gloomy and that there is no direct linkage between the authoritarian devolution of the Putin regime and the country’s deteriorating educational situation. I personally doubt that they are correct. Of course, one may try to dub Russia's troubles as simply "challenges" that we all need to overcome at some point, yet one should also remember that such challenges usually have authors and consequences. One of the Russian participants suggested that perhaps those in Europe who want to further cooperate with Russian universities should refrain from referring to such concepts as soft power and public diplomacy. The reason? They have mostly negative connotations in the Kremlin. Do we need any better proof for the growing alienation between Russia and its western neighbors?