Russian human rights groups have never had it easy. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has only made matters worse, sparking an unprecedented wave of repression and forcing many activists to emigrate. Russian dissident civil society has been able neither to prevent full-scale war nor to mobilize any significant part of the population for open anti-war protest. Yet nor has it been entirely passive; instead, it has tried to resist using the means available under the circumstances. How have activists made sense of the new reality and reorganized their work to continue defending political rights?

This memo looks at the case of OVD-Info, a leading project fighting against political repression in Russia. Our goal is to identify the key lessons that can be drawn from the experience of OVD-Info about the capacity of Russian civil society to continue with protest activities. Drawing on in-depth expert interviews with OVD-Info members[1] and media monitoring, we describe how the organization has adjusted its goals and strategies as the Russian government has persisted in its gruesome aggression against Ukraine.

We find that OVD-Info was able to foresee the trajectory of the Russian regime and to prepare for the new repressive turn. Its relentless work to provide legal aid to victims of repression and maintain autonomous horizontal protest networks demonstrates that, contrary to popular belief, Russian dissident civil society is neither “dead” nor “passive.” Even if it cannot be expected to overthrow the dictatorship from below, it still needs external support, as such horizontal networks are the only chance for Russia to develop a political system that would be accountable to its citizens and based on the rule of law.

Looking into the Abyss: History of the Movement and the 2021 Watershed

OVD-Info was born in early December 2011 in Moscow, as a new wave of protests that would become known as “the Bolotnaya movement” (2011-2013) was facing unprecedented repression. The organization’s founders began by publishing lists of detainees on their freshly created website. From there, the project grew exponentially, combining careful monitoring of protests and repression with concrete legal assistance in courts and police stations. In the years that followed, OVD-Info would play a crucial role in the fight against political repression, closely monitoring the major protest events and criminal cases that took place in Russia’s urban areas and becoming one of the most successful grassroots projects supporting victims of political persecution.

Today, OVD-Info presents itself as “one of the biggest Russian independent projects working on the ground, with around 400 lawyers, 7,000 volunteers and 190,000 private donors.” Its work has two main foci: providing round-the-clock, on-site legal assistance to detainees and gathering large-scale data on political repression in Russia. While repression has gradually intensified ever since the organization’s formation, 2021 represented a major watershed, for several reasons.

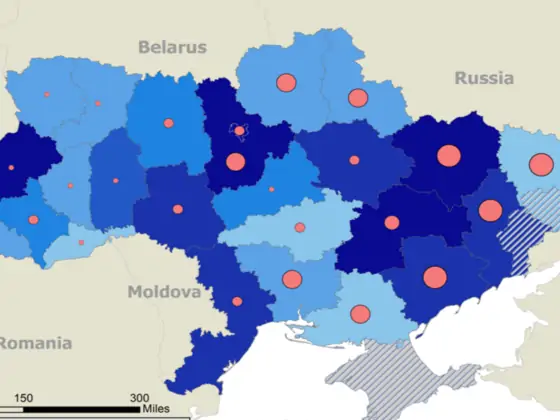

In 2021, Russia was shaken by a massive wave of protests in support of Aleksei Navalny, who had been arrested upon his return to Russia after having recovered from being poisoned. Thanks to its national network, Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) was able to organize rallies in many regions, in contrast to earlier waves of protest, which had been concentrated in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Detentions, arrests, and abuses by law enforcement were widespread, occurring in many places to which OVD-Info had not yet extended its reach. Concurrently, OVD-Info itself faced threats, including being designated as a foreign agent, while the oldest Russian human rights organization, Memorial, was forced to close down.

For the organization’s activists, who by this point had a decade’s experience of observing cycles of protest and repression, the events of 2021 were a clear signal that the nature of the regime was changing rapidly. In their view, the Kremlin was intentionally destroying the organizational infrastructure of civil society and mechanisms of political participation so as to foil any grassroots mobilization against the government.

Impelled by these developments, OVD-Info immediately took to work. The organization almost tripled its workforce and strove to find lawyers and volunteers in the “new” areas. Moreover, guided by the principle that “no one is irreplaceable,” its activists consolidated the strongly horizontal structure of the network in order to avoid major disruptions in the event that key figures were to become inactive. Volunteers went through in-depth training in safety and security. The organization’s capacity for remote data collection and management was augmented, as was the 24/7 helpline for detainees and their friends and families.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 provided dramatic confirmation that OVD-Info’s assessment had been correct. Thanks to its foresight, OVD-Info had managed to increase its operational capacity before the start of the war, and thus found itself ready on February 24.

Wartime Activism: Networking, Insourcing, Sharing

In the first weeks following the invasion, OVD-Info channeled all its efforts and resources into documenting the suppression of spontaneous mass protests and providing legal assistance to detainees. This protest wave had no leaders or coordinators, which made it nearly impossible to carry on with street actions after meeting with a violent response from the state. Moreover, new legislation swiftly passed by the State Duma provided extensive legal grounds for choking dissident voices.

As the weeks went by and the mass protests faded, dissent came to take the form of guerrilla activism and “microprotests”—horizontally organized, small-scale actions that sought to breach the propaganda wall and spread alternative information. As explicit political conflict began to subside, OVD-Info started thinking up new strategies for supporting freedom of speech. The most prominent of these has been to use growing international interest in the project to give voice to dissident voices in Russia, enabling them to discuss their fight and the persecution that they face.

Since February 24, OVD-Info’s work has thus been reorganized along two main principles:

- Prefigurative: post-war Russia and its civil society must be transformed in line with the rule of law. This future transformation can only be driven by a proactive, resilient, and organized civil society, which must therefore be built today.

- Preventive: the war must end, and no such war must occur again. Long-term suppression of human rights within the country and the degradation of the state’s accountability have tended to produce external aggression. Therefore, respect for human rights must be prioritized as a means of ensuring global security.

Hence, OVD-Info’s mission in wartime Russia is to strengthen and rebuild an autonomous civil society capable of organizing into horizontal solidarity networks and, ultimately, influencing institutional decision-making. To that end, the organization pursues the strategies of networking, insourcing, and sharing.

Networking

The spike in state repression and the emergence of new protest movements called for the enlargement of the project in both numerical and spatial terms. Increasing the project’s capacity required achieving a new level of grassroots diffusion. The anti-mobilization revolts in several North Caucasus republics in September 2022 highlighted a gap in the OVD-Info network. In response, its activists intensified their efforts to reach out to regional activists and independent journalists, as well as to provide news about protests through their own media outlets. The goal was both to give voice to less prominent groups and to attract activists from new areas. It is important to stress that these activities do not involve any formal coalition-building, except for the occasional submission of co-authored reports to international organizations. Cooperation is mainly carried out through personal acquaintances and informal networking.

Insourcing

Before February 24, 2022, OVD-Info’s network numbered approximately 3,000 volunteers. By the time of our interviews, this figure had risen to more than 7,000. Our informants indicated that since the beginning of the full-scale war, more than 13,000 people had reached out with offers to contribute. The volunteer workforce mainly focuses on gathering and processing large amounts of data about protest events, detentions, arrests, abuse, and other violations, as well as coordinating such concrete actions as providing legal assistance and drafting reports.

Furthermore, OVD-Info has launched a project to help Russian grassroots human rights civil society organizations (CSOs) scale up. The main problem that grassroots CSOs face is a lack of resources, as they have effectively been cut off from foreign funding. As OVD-Info has many years of experience with grassroots collective action and has accumulated significant resources, it has decided to share these with its less experienced colleagues. OVD-Info often “lends” its volunteer workforce to other organizations to carry out specific tasks. These may include data management, digital development, graphic design and social media management, and on-site volunteer work of different types. This process of “insourcing” other CSOs’ work by loaning them volunteers makes a significant contribution to these smaller CSOs, enabling them to grow without building hierarchical top-down structures.

Sharing

Insourcing and sharing, which often overlap, are carried out informally, through personal ties, with no public advertising. Horizontal sharing of know-how and resources is seen as the most straightforward way of fostering an autonomous civil society capable of engaging in all forms of political participation, from formal institutions to informal initiatives. OVD-Info conducts training courses for the staff of other CSOs, teaching them how to coordinate volunteer work, safely and efficiently use digital resources, develop and provide round-the-clock services such as bots and hotlines, and deal with legal issues. OVD-Info also encourages worldwide media to use the data, reports, and texts that the organization publishes on its website to spread the word about the dire situation facing Russian civil society.

Conclusion

OVD-Info’s trajectory both before and since Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine yields important insights into the development of civil society in wartime Russia, as well as offering crucial warnings for the future.

First, it confirms the importance of using relations between the state and civil society as a litmus test for—and a predictor of—a regime’s future trajectory. A crackdown on oppositional NGOs is cause for alarm not just for NGOs themselves: it might indicate that something even more sinister is in the works. Taking such developments seriously is vital for at least two reasons. For one thing, it makes it possible to preempt the state’s repressive policies, just as OVD-Info did in 2021, when its assessment of the regime’s evolution prompted it to augment its capacity and outreach. This was crucial in enabling OVD-Info to continue operating after February 24, 2022, rather than collapsing under a new round of suppression. For another, a vibrant and autonomous civil society capable of making the state more responsive to citizens’ needs than to the leadership’s designs is a crucial line of defense against imperialist aggression. There is little doubt that it would have been more difficult for Putin to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine had he not systematically destroyed independent civil society in the years and decades before 2022—or had Russian civil society received more support from international partners. OVD-Info is actively trying to protect what is left of independent civic activism, in the hope that the rule of law in Russia will one day be reinstated, for the benefit of both Russia’s citizens and its neighbors.

Second, OVD-Info’s experience provides strong evidence countering the widespread perception of civil society in Russia as dead and buried. Contrary to the dismissive attitudes prevalent in the mainstream debate, dissent is still alive, and activists do manage to carve out some space to operate beyond the Kremlin’s control. The expansion of OVD-Info into new territories and activities (by enrolling on-site lawyers, IT specialists, coordinators, creative professionals, and more), as well as the surging numbers of eager volunteers, illustrate the potential for political and civic self-organization both within Russia and in the diaspora. While the government’s twenty-year-long effort to wipe out or coopt any independent projects poses an enormous challenge to the Russian opposition, dissident initiatives continue to sprout up all over the country and new sites of contention continue to emerge on the margins of the public space. This must be acknowledged to encourage autonomous civil society in its fight against both the war and authoritarianism.

Finally, OVD-Info represents a valuable example of efficient collective action under an increasingly authoritarian regime. Its tactics prioritize horizontality, grassroots participation, empowerment of other dissident voices, and autonomy in the quest for democracy, while the project’s mission is to become part of a broader plan for systemic change. Projects such as OVD-Info must be supported by transnational solidarity networks as steps down the long, hard path to a future democratic Russia.

Maria Chiara Franceschelli is a doctoral researcher at Scuola Normale Superiore in Florence, Italy. Her research investigates civil society and social movements in contemporary Russia.

Viacheslav Morozov is Professor of EU–Russia Studies at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies of the University of Tartu and Academic Director of the Centre for Eurasian and Russian Studies.

[1] The interviews were conducted in the spring of 2023. To protect our respondents, we have anonymized the interviews. However, we were given permission to name the organization and to describe its work in detail.