One of the most talked about consequences of recent events in Ukraine is a dramatic transformation in Ukrainian national identity. Social activists and various elites regularly assert their increased self-identification as Ukrainians, pride in Ukrainian citizenship, attachment to symbols of nationhood, and readiness to defend and work for Ukraine. Most speak of their own experiences or those of people around them, while others generalize these individual changes to assert a greater consolidation of the Ukrainian nation. They also frequently mention the putative inverse of this consolidation, alienation from and even enmity toward Russia. This is targeted primarily at the Russian state but sometimes also the Russian people, who are believed to overwhelmingly support the Kremlin’s aggressive and undemocratic policies.

To what extent do popular opinions coincide with those of activists and elites? By comparing the results of two nationwide surveys conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) in February 2012 and September 2014, I examine changes in popular opinion for a period encompassing Ukraine’s Euromaidan protests and the early stage of the war.[1] In addition, focus group discussions held by KIIS in February-March 2015 in different parts of the country reveal the nuances of certain preferences and the motivations behind them.

I analyze change in two main dimensions of Ukrainian national identity, its salience vis-à-vis other social identifications and its content (i.e., the meaning people attach to their perceived belonging to the Ukrainian nation). I find that not only has national identity become more salient but its content has considerably changed, which primarily manifests itself in increased alienation from Russia and a greater embrace of Ukrainian nationalism. At the same time, popular perceptions are by no means uniform across the country, but the main dividing line lies between the Donbas and the rest of the country.

One aspect of the identity content that deserves particular attention has to do with the roles of the Ukrainian and Russian language. While many Russian speakers proudly assert their Ukrainian identity, which they link not to ethnic origin or language practice but to civic belonging, public discourse reveals conflicting opinions about the consequences of this identity choice for language use in society. While Ukrainians largely support the uninhibited use of Russian, they also want the state to promote Ukrainian, which they perceive not only as the language of the state apparatus but also as a national attribute. The failure of the post-Euromaidan leadership to adopt measures to promote the use of Ukrainian is bound to provoke discontent among a large part of society which views the titular language to be an essential element of national identity.

The Increased Salience of National Identity

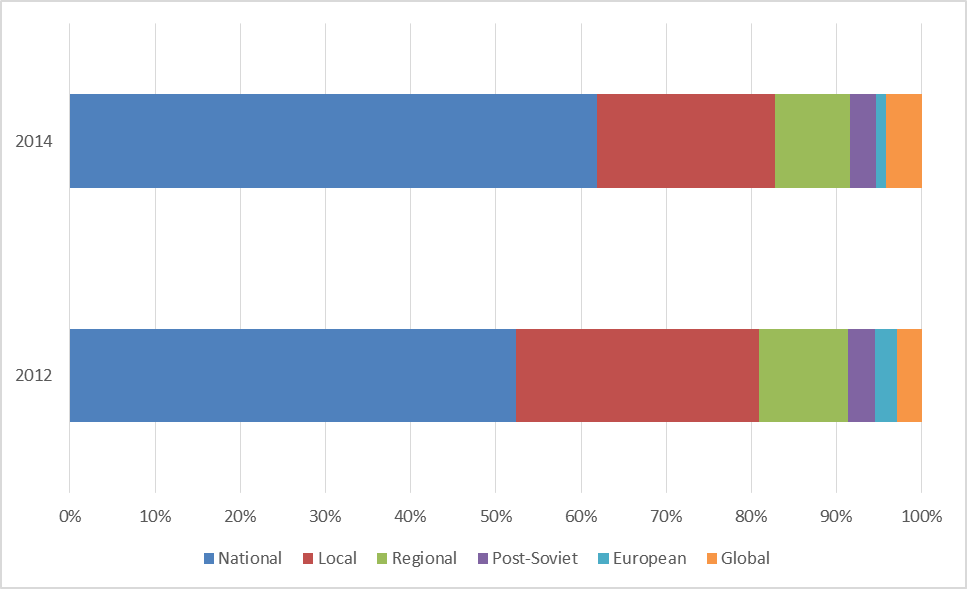

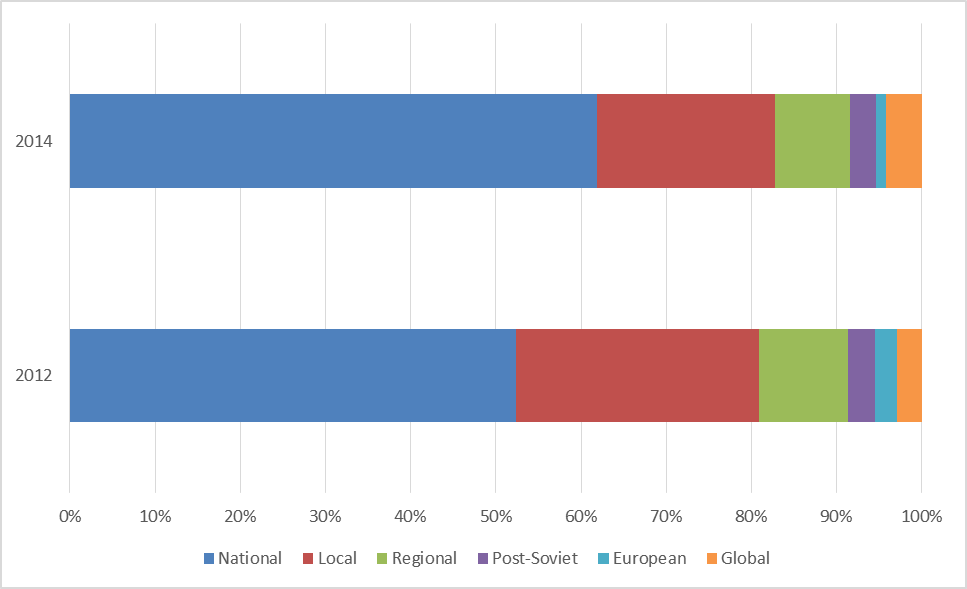

Both the 2012 and 2014 surveys included a question on the primary territorial identification of respondents. It asked them who they considered themselves to be primarily and gave a list of options encompassing various levels from local to global. In both surveys, the national identification clearly prevailed over local, regional, post-Soviet, European, and global ones (Figure 1). In 2014, 61 percent of respondents in the nationwide sample preferred to identify as citizens of Ukraine, in contrast to 21 percent who identified with their city or village and 9 percent who identified with their region. The other options scored lower than 5 percent, but it is worth noting that global identification turned out to be no less popular than the post-Soviet one. Moreover, in comparison with the 2012 survey, national identification increased by 10 percent, while local identification decreased by 7 percent and regional identification remained virtually unchanged. In other words, the gap between national identity and its competitors has considerably widened.

The prevalence of national identity is not evenly distributed across the country, however. This identity clearly predominates in the west and center, and it is also more salient than other territorial identifications in most eastern and southern regions. By contrast, in the Donbas it is only the third most salient, after regional and local identities.[2] In the west and center, the salience of national identity increased between the two surveys, but in the Donbas it significantly decreased while that of regional identification increased. This means that Donbas residents increasingly distinguish themselves from the rest of Ukraine and perceive themselves as “Donbasians” rather than as Ukrainians. This is hardly surprising in light of their widespread support for the separatist activities that Russia has provoked since spring 2014.

Focus group discussions help to elucidate complex dynamics of national identity. This identity can be related to both the nation and the state; those people who are discontent with state policies are less likely to develop or declare such identification than those who support the authorities. Moreover, while a feeling of empowerment after the Euromaidan victory contributed to a stronger identification with the Ukrainian nation, an opposite sense of powerlessness due to the ensuing economic crisis has worked to decrease the salience of national identity. For some, a strong attachment to Russia virtually predetermined a negative attitude toward the supposedly anti-Russian Euromaidan protests and policies of the post-Euromaidan government, but such an attitude was exceptional.

Greater Acceptance of Ukrainian Nationalism

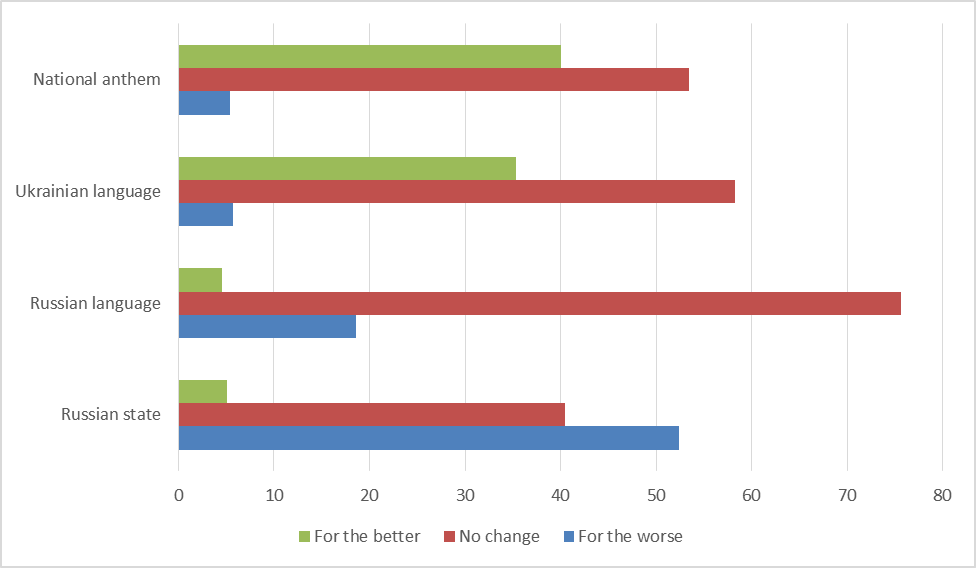

The most obvious change in the content of Ukrainian national identity, though a far from straightforward one, has to do with attitudes toward Russia. In the 2014 survey, attitudes toward the Russian state were found to have drastically decreased “over the last year,” since before the Euromaidan and the war: 28 percent said their attitude had worsened “a lot” and 25 percent said their attitude had worsened “somewhat” (Figure 2). A change for the worse was to be found in all regions except the Donbas, which again differed sharply from other eastern and southern regions.

However, a negative attitude toward the Russian state did not equate with alienation from the Russian people. Respondents were asked to express their opinion about the following statement: “Whatever the authorities do, the Russian people will always be close to the Ukrainian one.” Twenty-four percent of respondents fully agreed with this view and 40 percent “somewhat agreed,” while only 11 percent objected. Agreement with the statement turned out to be much stronger than disagreement even in the rather nationalist-minded West.

Most focus groups participants stressed that their negative attitude toward the state does not extend to the Russian people. However, some felt Russians were guilty in not only being afraid to protest but also in preferring to believe official propaganda. Even more participants doubted that Russians could still be considered “brotherly” to Ukrainians as Soviet propaganda once taught them to believe. Some argued that other peoples, like Poles, Georgians, or Lithuanians, were now more “brotherly” to Ukrainians than Russians. Such ambivalence seems to reflect a contradiction between established beliefs and new developments.

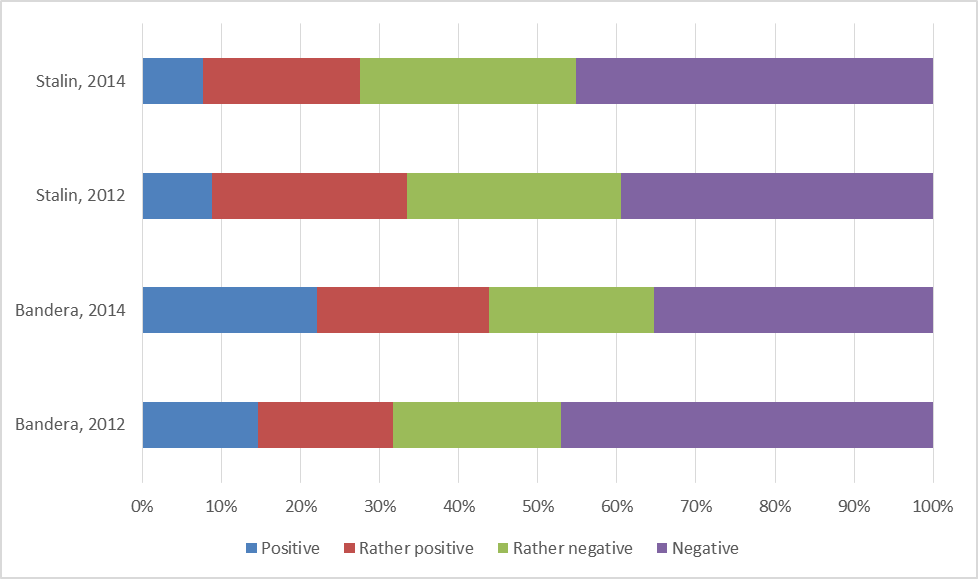

Another major issue concerns perceptions of Ukrainian nationalism in the past and present. Although post-Soviet changes in these perceptions continue to be constrained by lingering Soviet stereotypes, the ongoing Russian aggression facilitates the embrace of nationalist beliefs. For example, attitudes toward Stepan Bandera, a symbol of the Ukrainian nationalist resistance to Soviet and Nazi rule during and after the Second World War, markedly improved between the 2012 and 2014 surveys, even though somewhat more people still view him negatively than positively (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the attitude toward his perceived antagonist Joseph Stalin, who ultimately crushed the nationalist resistance in Ukraine (and other parts of the Soviet Union), further deteriorated. While in 2012 the attitude toward Bandera was roughly as negative as toward Stalin (53 percent versus 56 percent), in 2014 it was far less negative (42 percent as compared to 62 percent). Only in the Donbas did the perception of Bandera become more negative than two years before and the perception of Stalin became less negative.

Although many focus group participants persisted in viewing nationalism as implying national exclusivity or even Nazism, most argued that nationalism means nothing more than a love for one’s people and the desire for a free country. Many argued that nationalism plays an important, positive role in other societies, including those they view as examples for Ukraine. Finally, a widespread acceptance of Ukrainian nationalism was exhibited in response to the question of who could be considered Ukraine’s national heroes; most focus group participants referenced figures featured in the nationalist narrative of Ukrainian history rather than those favored by Soviet propaganda.

Acceptance of Russian, Primacy of Ukrainian

Attitudes toward language, while also somewhat contradictory, differed markedly from other changes in identity content, in that they allow for the continued legitimacy of a linguistic situation that was molded by Soviet rule. In terms of self-reported change in attitudes “over the last year,” respondents in 2014 reported having better feelings about the Ukrainian language, with 35 percent reporting at least some change for the better and only 6 percent feeling a change for the worse (Figure 2). Here again, changes in the Donbas run contrary to those in all other regions. Remarkably, the attitude toward the Ukrainian language has improved roughly as much as toward the national anthem and flag, which indicates that Ukrainian citizens perceive the state language not only in legal terms as the language of the state apparatus but also in symbolic terms as a national attribute.

At the same time, while the Russian language has come to be viewed somewhat more negatively, particularly in the predominantly Ukrainian-speaking west and center of the country, most respondents did not change their minds about it. Similarly, while many focus group participants mentioned their greater attachment to and more frequent use of the Ukrainian language due to the Euromaidan protests and subsequent war, no one viewed these developments as reason to change their attitude toward the Russian language, let alone abandon their accustomed use of it in everyday life (primarily or in addition to Ukrainian). This means that for most people, a stronger Ukrainian identity does not mean a worse attitude toward Russian; speaking and/or liking the Russian language has not become generally perceived as incompatible with being Ukrainian, even among those who speak mainly Ukrainian themselves.

Such an attitude indicates the ethnocultural inclusiveness of the new Ukrainian identity. Importantly, however, the inclusion of and respect for people speaking different languages does not amount to recognition of equal legitimacy of the languages themselves; in other words, Ukraine is not generally perceived as a nation with two languages. While Russian is respected as the language of a large part of the population and recognized as an accustomed means of communication within the country and beyond, Ukrainian is valued not only for its communicative functions but also for its symbolic role as the national language. Accordingly, it is the Ukrainian language that respondents want the state to promote primarily, an opinion 56 percent of respondents shared in 2014. Only 5 percent opted for promoting the Russian language, 17 percent preferred the promotion of all languages equally, and 14 percent wanted the state in each part of the country to promote the language of the local majority. While a mere 10 percent of respondents wanted the Russian language to be excluded from all social domains, only 24 percent were willing to grant it the same status as that of Ukrainian, with a further 19 percent preferring an official status to be limited to “those territories where the majority of the population wants it.”

Implications for State Policy

The most obvious political effect of the ongoing consolidation of national identity in Ukraine is the considerably increased pressure by civil society on authorities to implement democratic reforms and repel Russian aggression. In addition to removing hangers-on from former president Viktor Yanukovych’s regime and eliminating corruption, this pressure aims at reinforcing the army, reorienting foreign policy to the West, and acknowledging national (and nationalist) traditions in education, media, and so on.

With regard to language policy, however, this pressure is diluted by the understanding that ethnocultural demands have divisive potential. The only unambiguous requirement of the “pro-Euromaidan” public is for Ukrainian to remain Ukraine’s sole state language, something the state leadership intends to deliver even as it promises to guarantee the rights of Russian speakers. The new constitution currently in the process of adoption is likely to retain an exclusive status for Ukrainian nationwide while allowing the official use of Russian in those regions where it is preferred by a considerable part of the population. This would perpetuate the legal configuration introduced by the controversial language law of 2012, which the post-Yanukovych coalition tried to revoke in February 2014 but since then has been tacitly accepted as reconciling the interests of the country’s two main language groups.

At the same time, the data presented here indicates that while people largely support the uninhibited use of Russian, most citizens also want the state to promote Ukrainian. The overwhelmingly positive attitude toward the Ukrainian language provides an opportunity for authorities to secure the use of Ukrainian in the public sector and resort to affirmative action to enhance its role in market-regulated practices where Russian currently prevails. For example, public servants could be strictly required to use Ukrainian in communication with Ukrainian-speaking citizens, something many of them still fail to do. At the same time, the state can use tax breaks, quotas, and other instruments to stimulate the production and distribution of Ukrainian-language books, movies, songs and web resources.

While the post-Euromaidan leadership rhetorically supports the national language, it has almost entirely refrained from implementing any measures that can promote its use, likely out of fear of alienating Russian speakers. This attitude is shortsighted and bound to exacerbate the disadvantaged position of Ukrainian vis-à-vis Russian, provoking discontent among a large part of society that considers such an outcome unacceptable for a post-Euromaidan Ukraine fighting against a neoimperialist Russia.

Figure 1. “Who do you consider yourself primarily?”

(February 2012 and September 2014, by percentage)

Figure 2. “How has your attitude toward the following changed over the last year?"

(September 2014, by percentage)

Figure 3. Attitudes toward Bandera and Stalin

(February 2012 and September 2014, by percentage)

Volodymyr Kulyk is Head Research Fellow at the Institute of Political and Ethnic Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

[PDF]

[1] The 2014 surveys and 2015 focus group discussions were funded by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (University of Alberta), and the 2012 survey was funded by a grant from the Shevchenko Scientific Society in America. Since the 2014 survey did not include Crimea, Crimean respondents in the 2012 data were excluded in order to make the responses comparable.

[2] The Donbas includes both Ukrainian- and separatist-controlled territories.

For further reading:

Henry E. Hale, Nadiya Kravets, and Olga Onuch, “Can Federalism Unite Ukraine in a Peace Deal?,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 379, August, 2015

Scott Radnitz , “The Psychological Logic of Protracted Conflict in Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 343, September, 2014

Theodore Gerber and Jane Zavisca, “Policy Memo: Pro et Contra: Views of the United States in Four Post-Soviet States,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54, November, 2014

Polina Sinovets, “The Return of Language Politics to Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 318, April, 2014