(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) As Western countries argue about lethal aid provision to Kyiv and Russian forces continue to assert their presence on the other side of the border, Ukraine seems to be constantly in the news these days. Caught between East and West, Ukraine has similar divisions at play within the country, mainly between the Center and West and the South and the East. These divides manifest themselves in many ways across the political, cultural, and socioeconomic spectrums, including in local responses to the coronavirus pandemic. We decided to measure variation in mask-wearing—a politically tinged manifestation in many societies—across different parts of Ukraine. We find that while levels of mask law adherence seem to follow the traditional South and East vs. West and Center breakdown, the results appear tied more to socioeconomic and cultural factors than to the trope of divided pro-Russian vs. pro-Western political camps.

Methodology

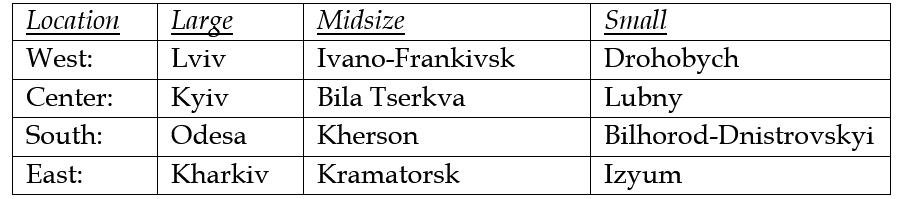

To assess variation, we employed both quantitative and qualitative methods of analysis. First, we measured mask law adherence in three cities of varying sizes in the West, Center, South, and East.

In each city, we positioned ourselves in two supermarkets and recorded people’s mask-wearing habits upon entry for one hour. Observations were made during early weekday afternoons to keep the crowd consistent. We separated customers’ habits into four categories, as shown below:

We also addressed other variables which may impact mask-wearing, including the weather and changing COVID-19 case numbers. Regarding the former, we figured that colder weather might induce people to wear masks more often, so we tried to keep the outside conditions at the time of observation constant. Additionally, we ran analyses on differentiation in local coronavirus case numbers to see if they would impact our study, and we found that there was minimal evidence for any correlation between local case numbers and levels of mask law adherence.

Base Results

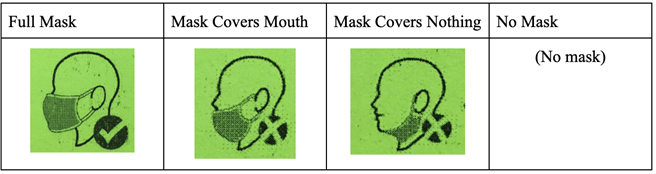

We recorded 6,168 observations across 23 stores in 12 cities from March 29, 2021, through April 16, 2021 (with the exception of our observation in Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi on March 19). Figure 1 shows the regional breakdown in mask-wearing habits and confirms that the South and East regions of Ukraine generally have lower levels of mask law adherence.

Figure 1. Mask Wearing by Region

Clearly, the South showed by far the lowest percentage of “Full Mask,” with around 53 percent compliance, followed by the East with about 71 percent, and then quite similar results for the Center and the West (77 percent and 79 percent, respectively).

Figure 1, however, can only provide a basic numerical understanding of trends in Ukrainians’ mask-wearing habits. While the South and East showed generally lower levels of mask law adherence than the West or Center, the question of “why” is not satisfactorily answered by these figures. Thus, we added a qualitative portion to our quantitative analysis, in which we held informal conversations with 55 Ukrainians of various ages and home regions on mask-wearing dynamics. The subsequent sections are driven by our data and by these conversations.

Negligible Evidence of Political Factors

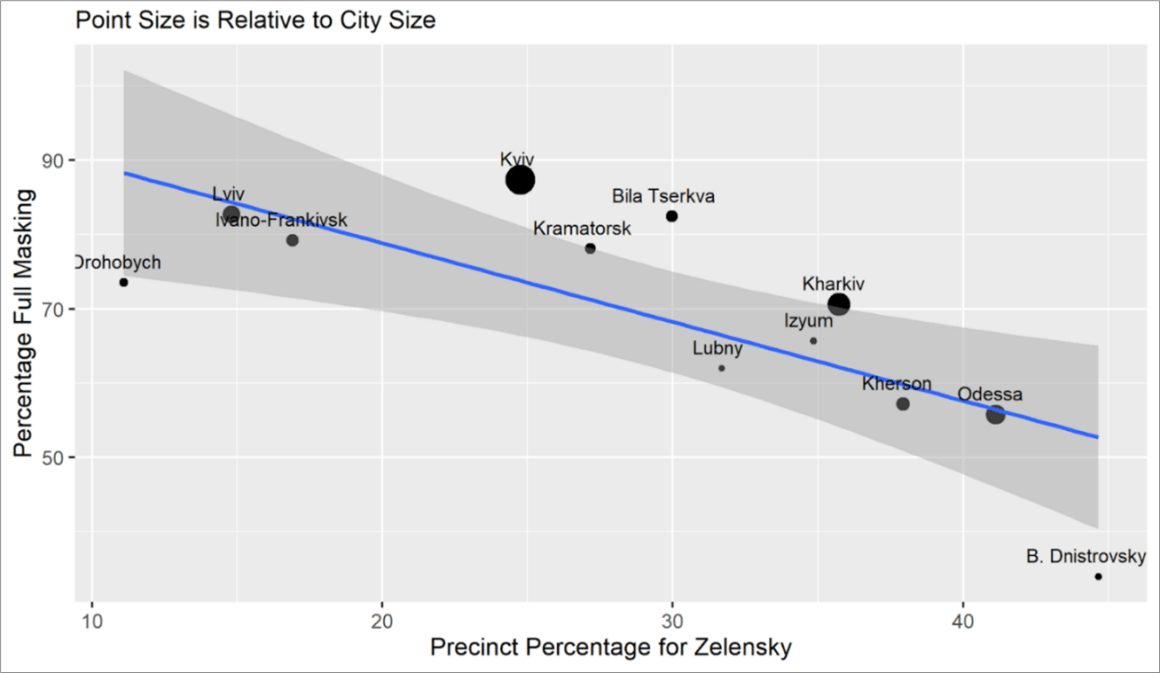

In many countries, the pandemic has been heavily politicized. But do political factors play such an important role in Ukraine? Our research shows that the answer is no. We believe that while mask-wearing practices correlate to some political phenomena, these phenomena themselves are likely not the causes of people’s mask-wearing choices. We initially surmised that if an area of the country was more supportive of President Volodymyr Zelensky, residents may be more likely to follow government guidelines on masking. Our participants, however, were not confident that this was the case—only two pointed to this variable as a potential factor. A deeper look at this variable shows that indeed, pro-Zelensky views have essentially no positive effect on mask law adherence in Ukraine, and the relationship may be negative (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Relationship Between Percent Voting for Zelensky and Percent Full Masking

Certainly, the idea that support for Zelensky would translate to support for mask laws seems unfounded. This result has generally positive implications for Zelensky: Although polls show that 77 percent of Ukrainians believe that the government has handled the pandemic poorly, the pandemic has at least not been politicized in such a way that Zelensky’s skeptics are less likely to follow national public health guidelines.

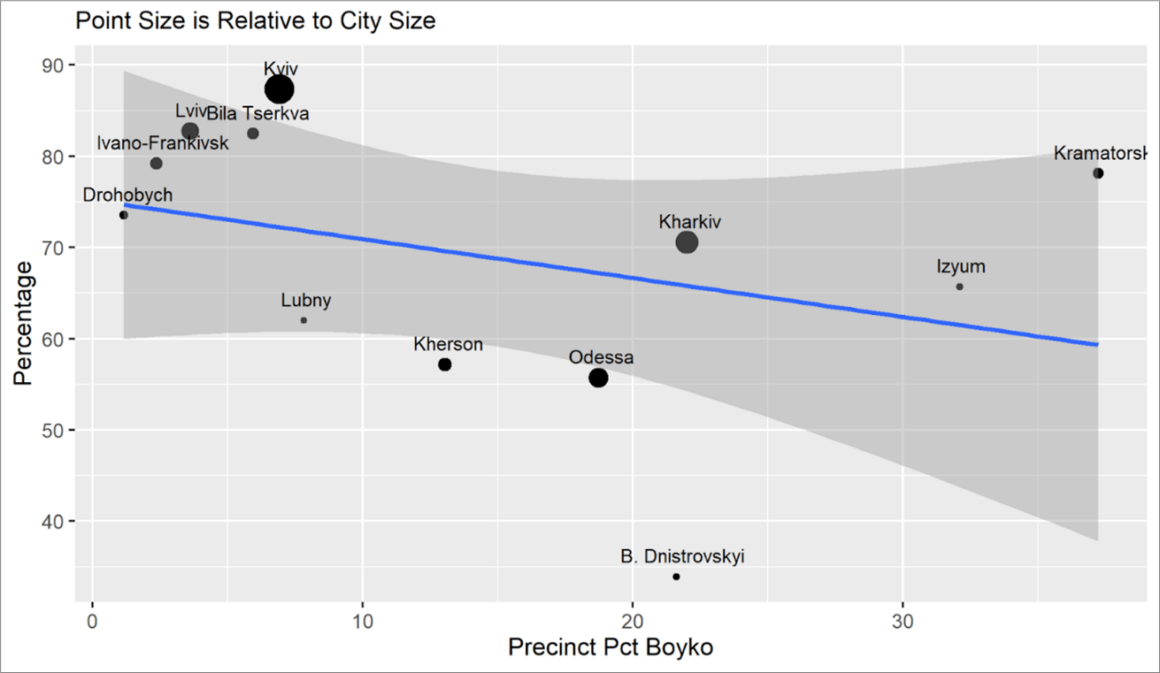

In addition to evaluating the impact of pro-Zelensky views, we also were interested in whether the degree of local support for a “pro-Russian” path for Ukraine impacted mask law adherence tendencies. Prior to the study, we figured that in areas where support for more pro-Russian policies is higher, mask law adherence might be lower due to Russia’s generally more lax approach to the pandemic than Europe’s. To measure this phenomenon, we used support for Opposition Platform-For Life candidate Yuriy Boyko as a proxy, given that Boyko was the most prominent mouthpiece for the more Russia-oriented segment of Ukraine’s population.

Figure 3. Relationship between Percent Voting for Boyko and Percent Full Masking

While the graph shows a slight negative trend, the fit is bad, and the relationship is difficult to confirm. Additionally, none of our participants mentioned this factor. One participant from Kyiv argued that “the more people are pro-Ukrainian—the more they tend to wear masks.” But the idea of what constitutes “pro-Ukrainian” is difficult to measure; Boyko voters likely believe that they are voting in Ukraine’s best interests just as much as Poroshenko voters, even if their visions of “pro-Ukrainian” policies are radically different. Additionally, we did not tie one politician to “pro-European” views; while Boyko represents the only significant pro-Russian faction in Ukraine and therefore is easy to use as a proxy, most other political figures, Zelensky included, follow largely pro-European trajectories.

In general, evidence is inconclusive that political factors have any significant direct effects on mask-wearing tendencies in Ukraine. If political factors do not drive this split, what factors do?

“Cultural Factors” Tend to Represent Familiar Divides

The “cultural” dimension of this question is difficult to measure quantitatively; however, among participants who provided their opinions on why there may be regional differentiation in mask-wearing tendencies, a large majority pointed to “cultural” factors as the main driving force behind any cross-country differentiation in mask-wearing habits. The cultural factors mentioned and the regional splits in the ways they were presented tend to support the traditional split between East/South and Center/West.

One cultural difference that numerous participants pointed to pertained to a difference in “mentality” between those who were more “European” and those who were more “Russian.” Oleh (Uzhhorod and Kharkiv) stated: “They’re just different people over there. They’re like Europeans. We’re like Russians.” Similarly, Roman (Kramatorsk) argued that “out in Lviv, the mentality is closer to the European one, so it’s from this that a lot of people out there wear masks.” Many others mentioned “mentality” as well.

Another widely cited cultural factor leading to potential regional differentiation is the idea of “responsibility.” Nine of our respondents directly mentioned “responsibility” in their comments—all from the South or the East. Many throughout the South bemoaned their fellow southerners’ “irresponsibility” or “carelessness,” even though we told none of them about our quantitative results. For example, Yulia (Kherson) stated that “people … in the South of our country are very careless… It’s like part of our character trait, to break the rules and believe that nothing will harm you!”

Ideas of “responsibility” were also found in eastern Ukraine, especially in Kramatorsk, a city where mask-wearing was relatively high. Ivanna (Kramatorsk) argued that “people here are concerned about their own safety and the safety of others. The city has a number of factories, and most people work there. That gives people a different outlook and a sense of responsibility to all.” Roman (Kramatorsk), meanwhile, said, “Why people obediently wear masks here is simple. The Soviet spirit hasn’t gone away. They were told to wear a mask, and it’s not important why.”

While differences in “responsibility” were popular explanations throughout southern and eastern Ukraine, many in western and central Ukraine cited variation in “culturedness” and “enlightenment” as driving factors for differences. Three respondents from Lviv offered the following explanations. Viktoriya: “Levels of culture—how well-informed people are, and use of media.” Volodymyr: “Levels of critical thought and knowledge—higher education and relative distance from civilization.” Dmytro: “People’s level of consciousness.” Others in central Ukraine mentioned somewhat similar factors. Katya (Bila Tserkva) argued that differentiation “can probably be explained by levels of education,” while Bohdan (Kyiv) argued that it was most likely a combination of “mentality and culture.”

This “culturedness and enlightenment” versus “responsibility” divide is obviously not infallible, but the general breakdown does confirm the idea that people believe that “mentalities” play a role, with the South and East generally preferring “responsibility” as a driving factor, while the West and Center prefer “culture” or “education.” One can also argue that this difference fits with the Europe/Russia breakdown. The East and South are more dominated by Soviet ideas of societal responsibility; the farther west, the more the idea of “culturedness” dominates, a concept that is quite possibly tied to its proximity to Western Europe, a perceived area of “high culture.”

Have these cultural factors been politicized? As shown in the previous section, there is inconclusive evidence that political factors affect people’s choices to wear a mask. Our participants also had differing opinions on the media’s role in differentiation, implying that this outlet of potential politicization also has not had a major impact on people’s decisions to wear masks. Only four people mentioned the media: two participants, Sveta (Vinnitsa) and Viktoriya (Lviv) stated that they believed that the media had an impact on differentiation but did not elaborate. Ayshe (Melitopol) mentioned the media, but only that people “don’t trust the media right now and are skeptical about the virus.” She did not refer to any differentiation in how people perceive the media’s messaging. Oleh (Kharkiv), meanwhile, flatly denied that the media played a role, saying that “this has nothing to do with the media.” In general, people did not perceive the media as having much influence on personal choices whether or not to wear a mask.

In total, many people cited “cultural” factors as having an influence over people’s mask-wearing decisions. Several people cited differences in “mentalities.” The different regional perceptions of responsibility, culturedness, and education enhance the notion of differences in mentality as well.

However, ambivalence about the role of the media reinforces takeaways from the section on political factors. Although mask-wearing did follow some of Ukraine’s typical political divides, direct political factors seem to have had significantly less of a clear impact on mask-wearing than did the underlying cultural factors that many would argue drive those divides. These divides have seemingly not been taken advantage of by politicians to a significant degree, and being more “pro-European” or “pro-Russian” does not seem to have anywhere near as much an impact on mask-wearing as do more fundamental aspects of people’s mentalities.

Influential Socioeconomic Factors

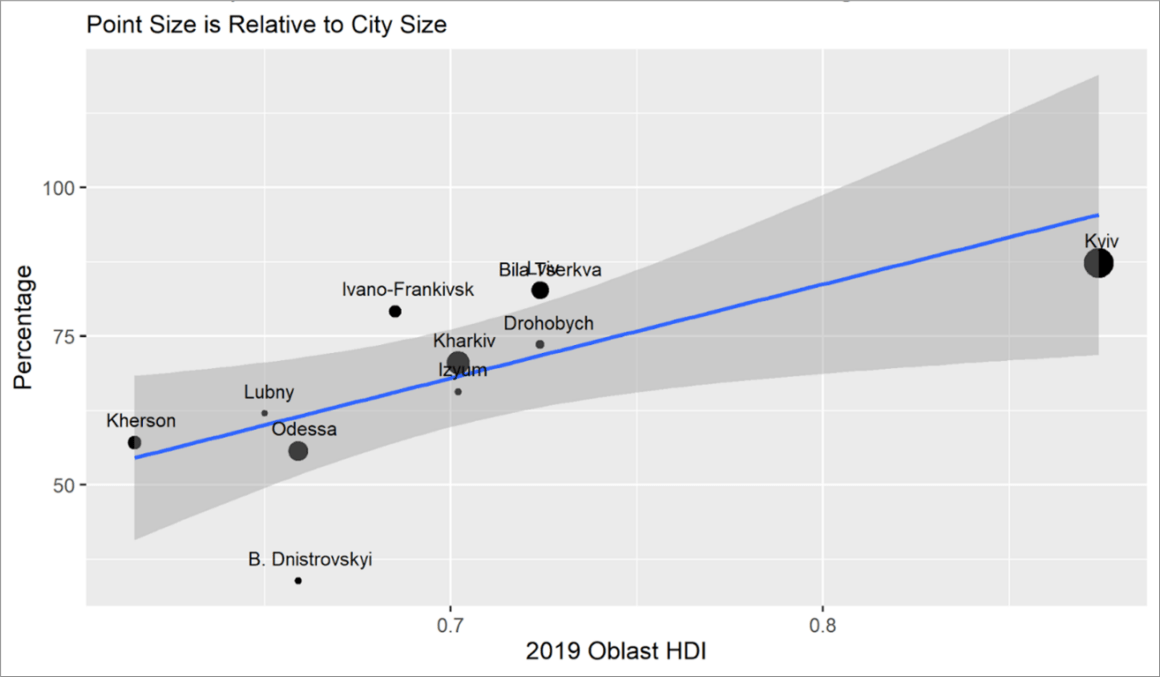

Finally, we analyze socioeconomic factors. Although participants tended to prefer cultural factors to socioeconomic factors as drivers of choice, there are a couple of socioeconomic variables that show a strong correlation with mask-wearing choices that we believe deserve attention. First, in Figure 4, we look at the oblast-level, or regional-level, human development index (HDI), which is calculated as the mean of life expectancy, education, and income.

Figure 4. Relationship between Oblast HDI and Percent Full Masking

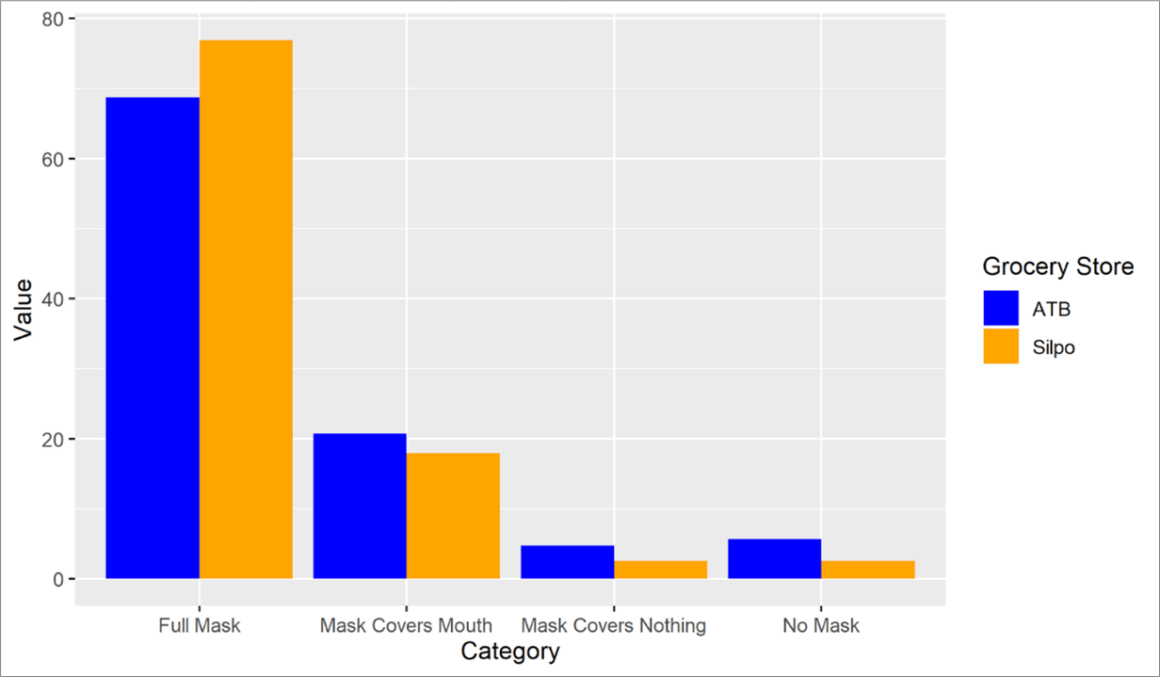

As is clear from this graph, oblast-level HDI has a strong correlation with mask-wearing, supporting the expressed idea that differences in adherence may correspond with “levels of education.” Interestingly, though, no other participants directly indicated that this sort of indicator would likely have an impact. We also analyzed the differences between the two main grocery store chains that we observed—ATB, the more discount store, and Sil’po, the more high-end store. At ATB, proper masking was lower than at Sil’po, while improper masking, correspondingly, was higher at ATB than at Sil’po, supporting our findings that higher income is associated with higher mask-law adherence in Ukraine. Figure 5 shows these trends.

Figure 5. Mask Wearing Tendencies by Grocery Store

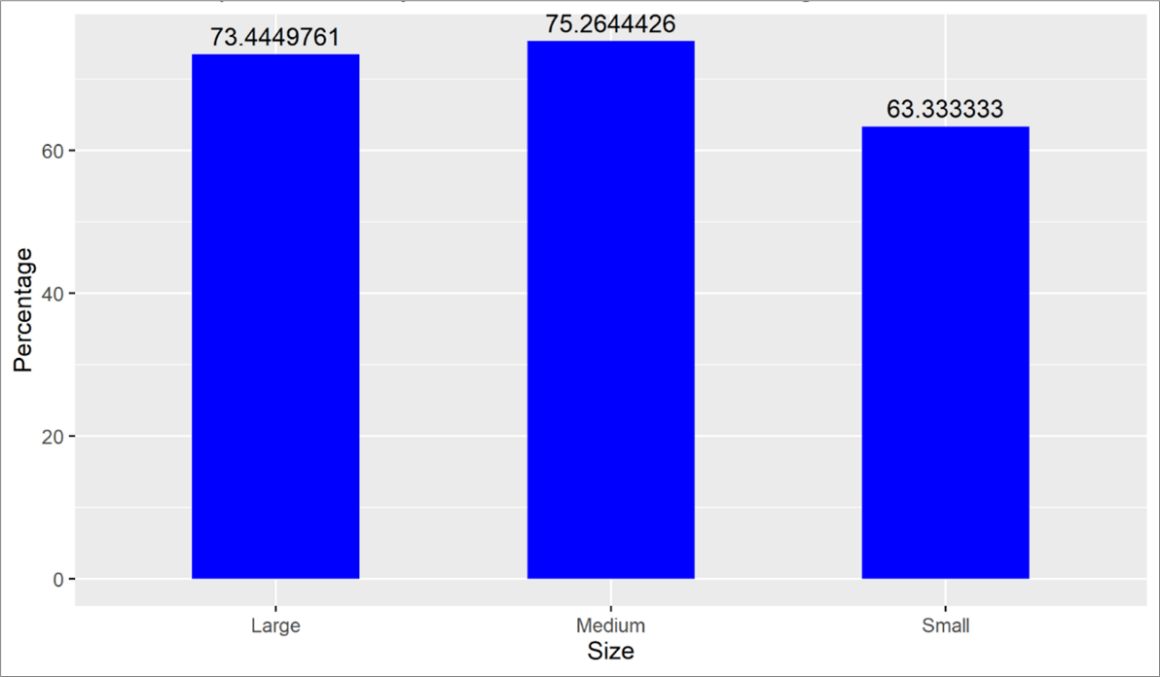

The final socioeconomic factor that we analyzed was the relationship between city size and percent full masking. In the United States, there is a noticeable urban-rural divide in mask-wearing; although the difference is nowhere near as stark in Ukraine, it is nonetheless observable, as in smaller towns, full masking appears to be around 10 percentage points lower than in cities. We postulate that in Ukraine, this factor also is likely tied to socioeconomic and cultural factors rather than political factors: Politics in Ukraine does not tend to strictly follow urban/rural lines. We show the results in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Relationship between City Size and Percent Full Masking

Overall, although our participants tended to prefer cultural factors over socioeconomic factors when coming up with potential reasons behind regional differentiation in mask-wearing, our research showed that certain socioeconomic factors correlated with differences in mask law adherence. In general, we find that higher HDI correlated with higher levels of mask wearing, and that more high-end grocery stores had better mask law adherence than more discount grocery stores. Along these same lines, in Ukraine’s small towns, where people are generally poorer than in cities, mask law adherence was noticeably lower.

Conclusions

While our initial hypothesis was correct that Ukraine’s South and East regions have lower levels of mask law adherence than the West and Central regions, the reasons behind this divide are less simple than “Russia versus Europe.” The correlation between a city’s “pro-Russian” vote percentage and its mask law adherence level was weak; instead, we found that socioeconomic factors had greater correlations to mask-wearing habits than external political influences. Furthermore, our participants largely neglected political factors in their explanations of differentiation in mask law adherence; instead, they pointed largely to cultural factors.

For Ukrainian policymakers, these findings are, in some senses, rather difficult, as the seemingly apolitical nature of our results makes it challenging for Ukrainian policymakers to manufacture a political solution to the problem of regional differentiation. The Zelensky administration already has done a thorough job of messaging; Ukraine’s former health minister, Maksym Stepanov, was constantly on TV prior to his being fired in May 2021, and his replacement, Viktor Liashko, began making TV appearances immediately after his appointment. Additionally, as we showed, adherence to mask laws has little to do with support for Zelensky himself, so the issue does not seem to be what the presidential administration is saying.

In other senses, however, the apolitical nature of these findings is reassuring: differences in mask-wearing in Ukraine do not seem to be tied directly to one’s support of or opposition to the party in power. Nor, for that matter, do they seem to be tied to foreign policy preferences. For a country where so many decisions revolve around the Russia vs. Europe question, the coronavirus situation may be seen as somewhat of a breath of fresh air.

Daniel Shapiro is a Consultant at the European Leadership Network in Yerevan, Armenia, and a Fellow at the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum. Research was supported by the University Consortium.

Dylan Hebert is a Teacher at the Dunya School in Baku, Azerbaijan.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 740