(PONARS Policy Memo) Russian-EU relations have dramatically worsened since Russia’s involvement in Ukrainian affairs in 2014. Mutual mistrust and suspicion have rapidly increased and many cooperative efforts have been canceled. Russia-NATO tensions have escalated and each side has sanctioned the other while the Russian economy has faltered. What have been the precise effects of these dynamics on the Russian-EU borderland regions? Which spheres have been damaged and which have proven resilient? Although Russian-EU cross-border cooperation has been seriously harmed, some cross-border activities have survived, particularly those involving well-established Russian-Finnish and Russian-Polish connections.

Cross-Border Relations before 2014: Steady and Improving

The EU acquired its common border with Russia as a result of two waves of EU enlargement: when Finland joined in 1995, and when Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland joined in 2004. Before these five countries joined the EU, Russia’s cross-border cooperation with each of them was influenced by the EU’s “Euroregion” programmatic and funding approach as administered by the EU’s Interreg and TACIS programs. Russia was initially considered a minor partner that would adapt to EU development patterns, which were based on decentralization and region-building. The approach was regarded as progressive and was bolstered by lavish, competitive EU funding.

While Russia was eager to foster trade with the EU, particularly to attract large investments for its north-west border regions, it was reluctant to grant them additional powers. Moscow was afraid that decentralization and increased foreign influence could foster regional separatism. It also felt that granting the regions more economic autonomy could be misused for the evasion of large-scale tax and customs duties (as happened before in other free economic zones, such as in Kaliningrad). For its part, the EU was reluctant to open its borders with Russia mostly out of concern about uncontrolled population flows, which it sought to address by establishing visa-issuing consulates in most Russian borderland regions.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, many regional administrations, especially the Russian-Finnish area of Karelia, were content to pursue practical cross-border cooperation projects. They tried to provide institutional networks for obtaining EU funding for joint projects, maintained cross-border business and social networks, and occasionally lobbied their central governments for increased funding.

The EU programs systematically evaluated all the border regions it shared with Russia, with planning consideration given to the borderland regions in the soon-to-be EU member states. The first wave of EU programs, between 2000 and 2006, involved Russian participation on technical assistance and official exchange visits. In 2009, the EU and Russia reshaped their cross-border cooperation and five main programs were modified: Kolarctic-Russia (involving the EU, Finland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden), Karelia-Russia, South-East Finland-Russia, Estonia-Latvia-Russia, and Lithuania-Poland-Russia. All of the cooperative programs were funded by both the EU and Russia, although the Russian contribution was less than a quarter. Most of the cross-border cooperation was focused on regional development and sustainable cross-border partnerships. For many small-scale projects, EU funding was often the main or only monetary source.

Damaging Influences from 2014

The fervent conflict in Ukraine fueled a sharp rise in tension between the EU and Russia. Cross-border cooperation was impaired in many ways. Militarization took place in border regions on both sides and the mutual sanctions and Russia’s worsening economic condition impacted cross-border trade and interactions. Many official high-level bilateral meetings were cancelled, including ones that were going to discuss cross-border cooperation issues.

The EU sanctions on Russia directly prohibited or seriously challenged the activities of the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which were involved in financing the border regions. The EU sanctions targeted five leading Russian banks, which also complicated some trans-border transactions. Investment risks rose for European entrepreneurs who were considering projects in those regions. The Russian food embargo limited to 5 kg per person the amount of foodstuffs that Russian tourists and travelers could bring back from Europe. The devaluation of the ruble in the second half of 2014 further decreased Russian purchases in neighboring EU regions.

The Baltic countries and Poland were particularly wary of Russian actions toward Ukraine. Lithuanian president Dalia Grybauskaite made some especially harsh public comments about Vladimir Putin’s methods and policies. Shortly after her November 2014 statement calling Russia a terrorist state, the Russian authorities introduced firm customs controls on all Lithuanian trucks (supposedly targeting unscrupulous carriers), which produced a bilateral customs war that lasted for several months.

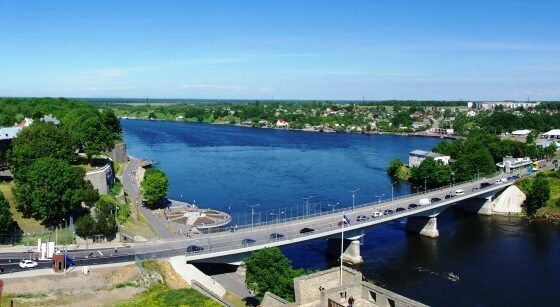

In September 2014, Estonia claimed that one of its Internal Security Service Officers, Eston Kohver, was abducted from Estonian territory by Russian agents. Russia claimed that Kohver was arrested for crossing the border illegally. Kohver was sentenced to fifteen years in jail, but was exchanged for an imprisoned Estonian security officer in September 2015. The incident induced Estonia to begin to delineate and securitize its border with Russia, which was strongly condemned by Moscow. Estonia also created a new border task force, proclaimed its intention of building a border fence, and refused to participate in the planned Zapad-2015 joint border guard training exercises. The other two Baltic states followed Estonia’s lead in most of these respects.

Estonia and Latvia were particularly afraid that Russia could try to repeat the “Crimean scenario” in Estonia’s Ida-Viru county or in Latvia’s Latgale region, areas that have serious socio-economic problems and large Russian-speaking populations. In some cases, Russian aircraft and warships were accused of violating Baltic state borders, particularly Latvia’s. The perceived threats led to escalating militarization and NATO and Russia both began to hold large-scale military exercises and reconnaissance maneuvers in the region.

In 2015-2016, Russia was accused of using refugees entering the EU from Russia as part of its “hybrid warfare” against the West. The claim was that Russia was soliciting refugees to travel to the EU and was not cooperating with neighboring EU states on deportation measures. Finland, as a result of bilateral presidential talks in March 2016, ultimately managed to get Russia to cooperate on cross-border migration flows. Estonia and Latvia took unilateral measures and began to solidify their borders and increase the numbers of border guards.

The Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, surrounded by EU states, was not immune to problems. Worsening Russian-Polish relations over Ukraine and the election of hardliner nationalist President Andrzej Duda in August 2015 did not initially damage bilateral cooperation. Despite some pessimistic predictions, population flows between the two did not decrease. The two have a transit visa regime; Kaliningraders and Poles have special cards allowing Poles to travel anywhere in the Kaliningrad province (but not to mainland Russia) and Kaliningraders can travel to Poland’s Warmia-Mazuria province (but not beyond). Eventually, however, high politics influenced local cooperation. In July 2016, Poland suspended this transit regime due to the NATO Warsaw summit and the visit of Pope Francis, and they have not been fully lifted since. Polish Interior Minister Mariusz Blaszczak claimed in September 2016 that the suspension of small border traffic with Russia was due to several “strong prerequisites” threatening Polish and EU security. In March 2017, a representative of the Ministry of the Interior specified that Poland was afraid of Russian special services’ increasing activity and of Kaliningrad province’s ongoing militarization.

Russian propaganda and nationalistic Russian activities were (and are) present in the borderland areas. For example, to justify its “struggle against fascism” in Ukraine, Russia has persistently exploited its victorious role in World War II in its media messaging. For many in the EU borderland states, issues involving World War II are highly emotional, and they have seen the Russian propagandistic narratives as attempts to meddle in their internal affairs. There have also been cases when Russian passenger cars decorated with St. George Ribbons, identified as a pro-Putin symbol since the Donbas insurgency, were not allowed to enter into the EU, or were subjected to nitpicking inspection by EU border guards. In 2015 and 2016, in celebration of May 9 Victory Day, members of the Russian pro-Putin and nationalistic Night Wolves motorcycle club tried to ride across the Russian-Polish and Belarus-Lithuanian borders, but many of them were denied entry. In some areas, Russian border authorities tried to help Night Wolves riders cross the border, often to the irritation of officials on the EU side. It did not go unnoticed that Kaliningrad’s governor, Nikolai Tsukanov, took part in a 2015 Night Wolves ride into Poland. In another example, Estonian border guards in May 2016 did not allow a Pskov city delegation headed by the city’s vice-mayor across the border to celebrate “the 71st anniversary of the Great Victory” in Tartu.

Some Cooperation Currents Continued

Despite the assorted tensions and problems, Russian-EU cross-border cooperation never completely ceased. For Russia, the EU is too important a partner to cut all existing ties, while for the EU, curtailing cross-border cooperation would contradict its good neighborhood policies, and it generally does not want its longest land border to become an absolutely hostile zone. It is no wonder that in 2014, the European Commission decided to uphold the cooperation programs, though the option of suspending them was discussed. The most visible continued projects involve the modernization of checkpoints and roadways, environmental protection measures, and the development of tourist routes and repairing important tourist sites. Dozens of small-scale projects continued, which have created a pretext for local officials on both sides to continue to meet with each other and maintain contact between local governments and security services.

The EU and Russia have even launched several new programs, although most of these build on existent ones. While the Kolarctic-Russia, Karelia-Russia, and South-East Finland-Russia programs were mostly kept in their previous forms, the Estonia-Latvia-Russia and the Lithuania-Poland-Russia programs were updated—essentially they were divided into binational programs. This resulted in some local Russian border-region officials being invited to participate directly in some joint programming segments, for example on Black Sea issues. On paper, many of the joint programs are marked as running to 2020, though several are currently waiting to be ratified by the Russian parliament.

In 2015, Russia and Finland agreed to create the Saimaa Free Economic Zone. The project, however, was suspended in 2016 when the Russian government became disappointed with the performance of free economic zones in general and decided to re-evaluate their regulatory frameworks. Nonetheless, the wider St. Petersburg region and Finland are primary trading partners and continue to pursue a range of joint projects. In general, Russian relations with Finland and Poland were damaged far less than Russian relations with the Baltic states. But even in the Baltics, interactions never fully ceased because all parties want to prevent cross-border crime and alleviate times of high commercial traffic congestion.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

Russian-EU relations have experienced a sharp downturn in 2014 due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, resulting in damage to Russian-EU cross-border cooperation activities. The Baltic states have fared worse than have Poland and Finland, but even to this day, all remain highly vulnerable to worsening political relations. Some areas of cross-border cooperation have survived during the height of the tensions due to localized connections and the idea that a wholly unwelcoming border would be devastating to trade and local transborder communities both in the EU and in Russia. It would be in Russia’s interests to proceed with the EU’s regional cooperation programs, iron out the technicalities of the Saimaa Free Economic Zone with Finland, and resolve travel and transport issues between Kaliningrad and its neighbors. The successful implementation of joint programs, even if relatively small, would contribute to improving everyday relations between Russians and Europeans, even during a time of ongoing turmoil in “high politics.”

Serghei Golunov is Professor at the Center for Asia-Pacific Future Studies at Kyushu University, Japan.

[PDF]

European Union Center of Excellence, McGill University, Montreal, Canada. This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.