In September 2013, at a speech at Nazarbayev University in Astana, Chinese Premier Xi Jinping announced plans to promote a “Silk Road Economic Belt” across neighboring Eurasian states. Over the next months, Chinese policymakers and analysts further outlined ambitious plans to promote regional cooperation, economic integration, and connectivity by funding large-scale infrastructure and development projects throughout the region. These include a series of land routes and high-speed rail links intended to connect East Asia with Europe (via Eurasia), South Asia, and the Middle East, as well as an accompanying maritime belt, supported by upgrades to ports and logistics hubs. Collectively, these two belts have been described as One Belt, One Route (OBOR) and, according to the South China Morning Post, the initiative represents the “most significant and far-reaching project the nation has ever put forward.”

Despite the project’s regional enthusiasm and official fanfare, the exact details of OBOR remain underdeveloped. Moreover, the vision rests on debatable assumptions about the allegedly mutually reinforcing relationship between external patronage, economic development, and political stability. The U.S. policy response to OBOR and its supporting initiatives has been typically schizophrenic across different governmental divisions. Eurasian and Central Asian-related agencies have emphasized the very close compatibility between OBOR and the U.S.-led New Silk Road (NSR) that emphasizes regional connectivity in Central Asia (and, by implication, diversification away from Russia). However U.S. officials and, critically, the U.S. Treasury, clumsily opposed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and in the fall of 2014 even lobbied, unsuccessfully, allies South Korea and Australia not to join the organization. Nonetheless, despite the bungling of the AIIB issue, there remains a range of legitimate practical and analytical questions concerning the OBOR’s imputed potential to transform the economies and polities of Eurasia. This memo will explore some of the challenges that the Chinese initiative is likely to confront in the areas of governance and promotion of political stability when interfacing with Central Asia’s patrimonial political systems.

U.S. and China-Led New Silk Roads: Two Similar Visions, Only One Real Funder

Central Asian observers see echoes of comparison between Beijing’s initiative and previously announced U.S. plans to support a “New Silk Road” (NSR) by promoting energy and infrastructure ties between Central Asia and South Asia (especially Afghanistan and Pakistan). However, beyond their similar labeling, the two geopolitical initiatives could not be more different: a cash-strapped U.S. foreign aid apparatus has allocated scant resources to the NSR, while Beijing, flush with over $3.6 trillion in foreign currency reserves, is preparing to allocate hundreds of billions of dollars to OBOR. The U.S. version establishes no new regional institutions or forums, instead repackaging existing projects such as the proposed Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) natural gas pipeline into the NSR’s thin portfolio. By contrast, China has recently funded and established a number of new dedicated regional banks to promote its vision, including a $40 billion NSR fund under the auspices of the People’s Bank, the new Shanghai-based BRICS New Development Bank, and the newly established AIIB. Finally, while the U.S.-led NSR has been associated with U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and disengagement with Central Asia as a region (albeit unintentionally), the OBOR very much underscores China’s global ascendancy as a leading donor and its new willingness to play a more assertive and central role in actively shaping the political and economic future of the neighboring regions.

China’s OBOR is being driven by a mix of international and domestic imperatives. Internationally, Chinese officials see OBOR as a way of expanding China’s economic engagement and political ties with neighboring states and regions, establishing new concrete ties that can serve as the basis of a political community that is increasingly responsive, if not completely friendly, to China’s foreign policy interests and domestic priorities. At the same time, investing in these new regional banks and development initiatives offers a potentially more productive use for accumulated foreign exchange reserves than maintaining them in U.S. treasuries, while these new projects can also potentially be used as part of the broader effort to internationalize the use of the renminbi. By channeling this investment through the New Development Bank, AIIB, and possibly even the still-underutilized Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Beijing sees opportunities to more effectively leverage its institutional voice in regional organizations into its own foreign policy priorities and regional goals.

Domestically, the development and stabilization of the restive western province of Xinjiang continues to inform discussion and justification of the OBOR; indeed, the cities of Urumqi, Khorgos, and Kashgar remain at the center of various proposed OBOR routes (west, north, and south). In addition, slowing rates of growth within China (from 10-12 percent to estimates of 5-7 percent) mean that domestic suppliers of the decades-long Chinese construction boom now require new overseas outlets to continue their activities. For example, without new external markets and large-scale projects, Chinese cement and steel manufacturers—the latter of which currently account for over 50 percent of global overcapacity—will face huge adjustment costs. Similar domestic dynamics characterize competition among Chinese energy companies for new plays, while even Chinese regions are similarly competing, as eastern coastal cities once did, to position themselves as dynamic transportation hubs. Many of these domestic actors play off and reinforce the official Chinese narrative about OBOR’s purpose, even as they pursue more parochial interests.

One Plan, Many Different Possible Unintended Consequences

The OBOR also carries a number of still unacknowledged risks, uncertainties, and unintended consequences. This is especially true for regions such as Central Asia and South Asia that are still burdened with governance and political challenges. In fact, the recent experience of Xinjiang itself suggests that large-scale infrastructure spending and external resources can, quite unintentionally, further fuel economic and social problems rather than ameliorate them.

Three risks seem particularly acute:

First, the severe governance challenges confronting nearly all of the Eurasian states where governance is already strained and absorption capacity is weak should give analysts and policymakers pause at the prospect of China suddenly dumping hundreds of billions of dollars into state-sponsored areas such as construction, transportation, and energy production. China has already announced plans to provide $46 billion in new funds to build highway and energy projects in Pakistan, a country that despite its status as a Chinese economic client has a poor track record of completing large projects in a timely fashion.

A recent case of Chinese funding of a major highway project in Tajikistan provides a further cautionary tale in how local elites can privatize non-conditioned Chinese patronage intended to fund public goods. Shortly after the Dushanbe-Chanak highway was opened in 2010, with about 80 percent Chinese funding, tollbooths appeared along the road. The company operating the toll was identified as Innovative Road Solutions, registered in the British Virgin Islands, with no previous corporate history nor record of bidding on highway management projects. Subsequent local investigative stories tied the offshore company to the President’s son-law, an allegation denied by him, estimating that it was opaquely funneling a private annual revenue stream to the government’s inner circle.

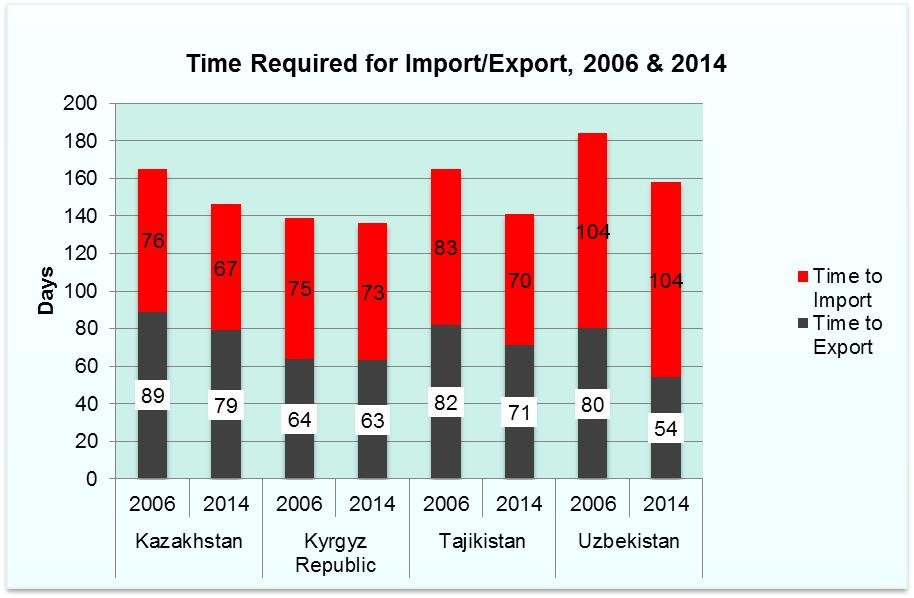

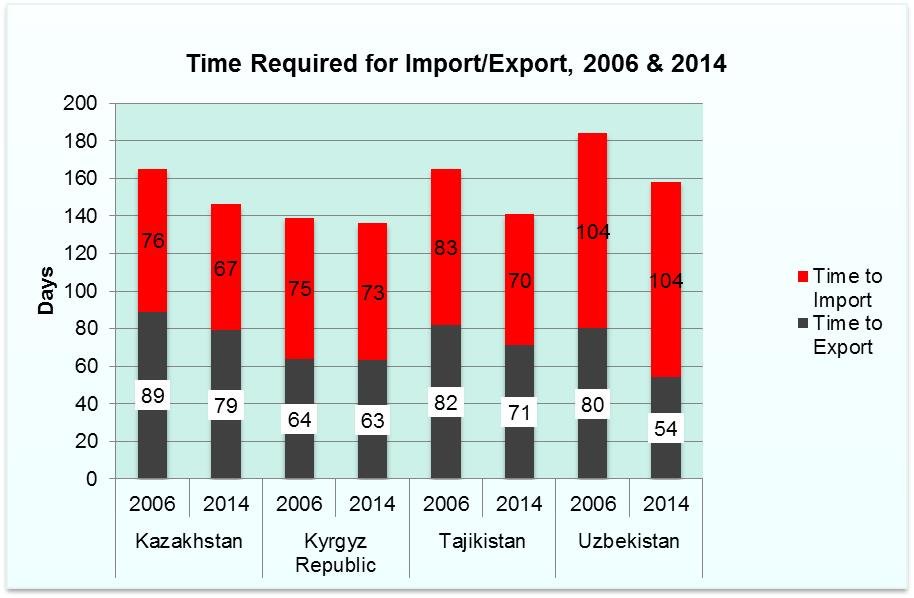

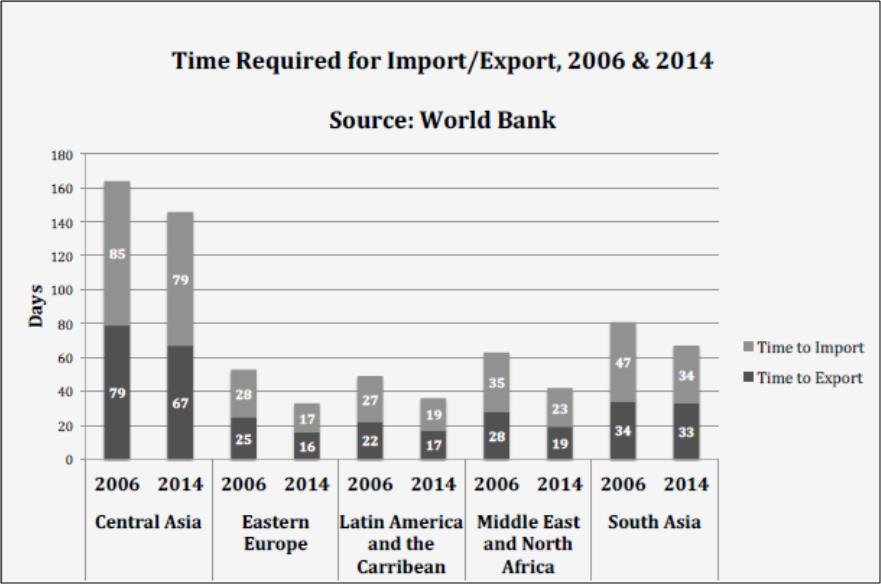

Furthermore, the assumption that more state-sponsored projects will somehow unleash private activity is also dubious. Data from the World Bank show only modest improvements in import/export times across the region between 2006 and 2014 (Figure 1), despite the introduction of many externally-led integration schemes and trading blocs. Indeed, the severity of informal trade barriers in Central Asia makes the region’s comparable times three times as high as Eastern Europe, Latin America, and even the Middle East, and even double those of South Asia (Figure 2). To be blunt: Central Asia remains the most trade-unfriendly region in the world, and the potential for externally-funded infrastructure to transform these entrenched practices is highly questionable. More likely, such projects, even if implemented, are likely to displace rent-seeking into other areas. Similarly, the sheer scale of the resources poured into the OBOR are likely to unnerve other regional investors who may balk at the prospect of competing with China’s largesse as they seek access to the same sectors.

Figure 1: The Problem of Central Asia’s Informal Trade Barriers and Border Controls

Source: World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business

Figure 2: Central Asia’s Informal Trade Barriers and Border Controls in Comparative Perspective

Source: World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business

More broadly, the case also highlights one of the biggest analytical and practical flaws in both the Chinese and U.S. visions of the New Silk Road: the assumption that the most important factor inhibiting economic growth and development in Central Asia is a lack of economic connectivity and regional integration. In fact, as John Heathershaw and I have argued in a recent issue of Central Asian Survey (March 2015), this assumption is based on empirical myths and analytical fallacies. Empirically, the Central Asian states demonstrate strong links to global financial markets, offshore havens, and legal processes such as international commercial arbitration and dispute settlement. In both the U.S. and Chinese visions, it is not clear why predatory elites and kleptocrats with access to new sources of rent will productively invest these funds in regional follow-up entrepreneurial efforts rather than divert these revenue streams offshore. At the same time, Western officials have failed to recognize the critical role played by Western accountants, auditors, legal advisors, providers of shell companies, residence permit regimes, Western bank accounts, and luxury real estate holdings in shaping and maintaining these global networks of corruption and graft.

There are also internal and external political challenges that OBOR proponents readily dismiss or are unable to confront. Chief among them is the idea that large-scale infrastructure will somehow magically mitigate internal conflicts and sources of instability. In fact, recent evidence from northern Myanmar or Baluchistan in Pakistan over the role of Chinese development aid suggest that external funds have fueled domestic ethnic tensions and furthered distributional conflicts. However, Chinese officials have been reluctant to acknowledge any kind of destabilizing role played by their investment and, instead, have been quick to blame “Western NGOs” for delivering bad news from these regions. At some point, Beijing planners will need to recognize that such funds, despite Chinese intentions to the contrary, create local perceptions about winners and losers that inevitably graft onto local rivalries and concerns. For example, the proposed China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad project, despite its potential commercial benefits, continues to meet fierce resistance among Kyrgyz government officials and analysts precisely because it furthers perceptions that China invests only for its own economic purposes and cares little if it stokes rivalries between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in southern Kyrgyzstan (the site of deadly ethnic clashes in 2010) over the region’s political and economic alignment.

Finally, OBOR will inevitably also send acute geopolitical signals. U.S. policymakers suffered a severe blow to their credibility and prestige as a result of their ill-timed lobbying for countries not to join the AIIB before the bank had issued even a single loan. However, the enthusiastic rush by 53 countries to join the AIIB means that Beijing may not exercise the degree of control over the institution that it probably assumed it would, prompting it to continue to channel funds bilaterally to favored political clients. Moreover, while Russia has remained publicly supportive of OBOR, and explores ways for it to work in partnership with the recently formed Eurasian Economic Union, it has clear concerns, along with India, at the political implications of such extensive Chinese investments in the region. Although both Delhi and Moscow may welcome a shift in authority away from Western-dominated international financial institutions, they will now have to confront more immediately and practically the realities of a huge Chinese investment footprint, unmediated by concerns about Western encroachment and influence.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Even if the OBOR is funded at a fraction of its current projections, it is an initiative that will likely have important regional impacts and deserves close scholarly and analytical attention. Unlike its U.S.-led counterpart, it will be supported by new regional mechanisms and institutions and is likely to pour unprecedented levels of external resources into Central Asia. At the same time, the enduring strength of Chinese assumptions about the benign developmental effects of OBOR may well clash acutely with local economic and political realities. At some point, an accumulation of local instability, blatant kleptocracy, and problematic projects may well force Chinese officials to rethink or question Beijing’s longstanding policy of non-interference in the domestic affairs of its aid and investment recipients.

Alexander Cooley is Director of Columbia University's Harriman Institute and Professor of Political Science at Barnard College, Columbia University.

[PDF]