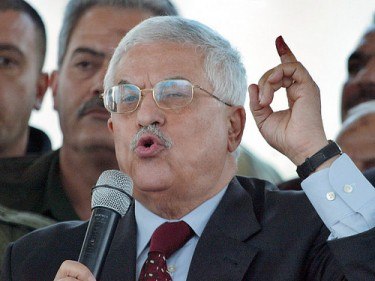

Foreign politicians are infrequent visitors to the North Caucasus. That alone would be sufficient reason to pay attention to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’ mid-March visit to the North Caucasian republic of Karachay-Cherkessia. What is the significance of such a visit for Russian domestic and foreign policy? There is no simple answer to this question. It is doubtful that Abbas’ visit to Karachay-Cherkessia would have a strong impact on Russian political dynamics either inside the country or on an international level. However, the picture is somewhat different if the visit is analyzed as part of a more general process.

First, the North Caucasus remains one of the most turbulent regions in Russia. That is what brings to it the attention of foreign states, as well as different non-governmental and network structures to the region. Overcoming the instability of the North Caucasus is a test of success for Russia as a state. Let us not forget that the North Caucasus is home to a significant Muslim population with extensive and divisive connections to the Islamic Middle East. In view of the ‘Arab Spring’ and especially the ongoing civil confrontation in Syria, Moscow fears that the Middle Eastern “fire” may reach the Caucasus and Volga regions.

This brings us to Russia’s interest in securing its channels of influence in the Middle East. Though Saudi Arabia and Qatar may not assist in this, Palestine and Jordan can be very useful. Moscow positions itself as a co-sponsor of the Palestine-Israel peacemaking process. And the Palestinians regard Russia’s co-sponsorship as some kind of counter-balance to the West. Through different contacts with Palestine, including on a regional level, Moscow sends a message to the Middle East – that it does not close off the North Caucasus to outside contacts, but on the contrary, welcomes pragmatic partnerships.

Second, while Russian leaders fear the strengthening of Islamists and the possible “export” of Middle Eastern and North African radicalism, they also want to play a bigger role in the Islamic world. Recall that, since 2005, Russia has had observer status in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). And the idea of multipolarity, supported from inside by the “dialogue of cultures and civilizations,” is one of the ideological pillars of Russian policy. Let us also not forget that Russian political and civic identity is still in its formation phase, and Muslims make up a significant part of the country’s total population. That is why Russia prioritizes constructive relations with the Islamic world, especially with countries and movements that focus on national and secular principles.

Of course, whether Abbas can be regarded as the leader of all Palestine is a different question. It is not clear if it is sufficient for Russia to develop relations only with Fatah and to ignore the Gaza-based Hamas. At the same time, Moscow must calculate the downside of developing deeper relations with Hamas, including its impact on Russian-Israeli relations, which Moscow has worked hard to cultivate.