(PONARS Policy Memo) Over the last decade, the Russian economy has undergone a pronounced turn toward consolidation and renationalization. The state continues to aggressively intervene in markets, passing new regulations, expanding its share of GDP, and ultimately driving out private companies. These actions, as well as repeated economic crises since 2008, have drastically reduced levels of competition in the majority of Russian economic sectors. Yet, even during this prolonged period of economic decline and stagnation, major Russian firms have remained profitable, partly thanks to a decreasing number of rivals.

Market consolidation can instigate a number of political and economic challenges in a country such as Russia. Low levels of competition impede attempts to increase labor productivity, hold back economic growth, and contribute to already high prices paid by consumers. This could lead to more political turmoil rising from below, as citizens withdraw their support for President Vladimir Putin’s government over economic concerns. Moreover, the emergence of monopolies in many sectors has bestowed immense political power on just a few economic actors. Large companies face fewer obstacles to achieving preferential state treatment and wield numerous levers to block modernizing reforms that might undermine their hold on markets. This may reduce foreign leverage on Russia’s government in the short term, since the state finds it is easy to prop up the small number of sanctioned firms. But as long as this process of monopolization continues, the long-term growth prospects for Russia are increasingly dim.

The Current State of Affairs

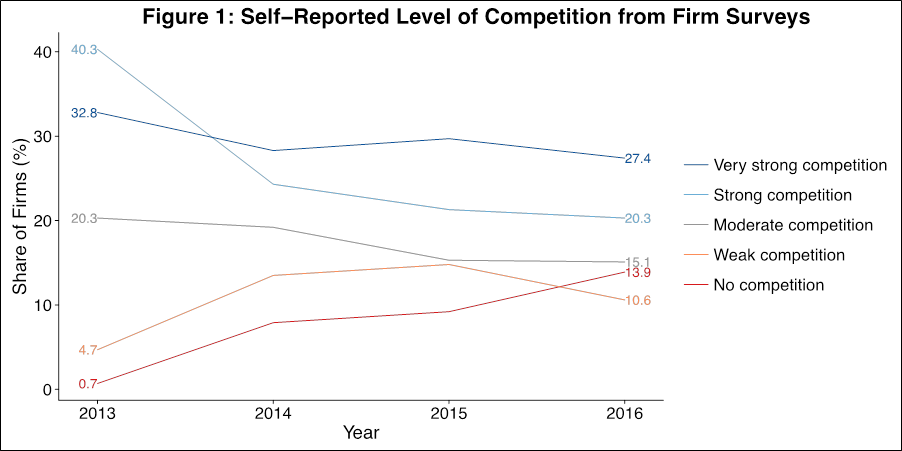

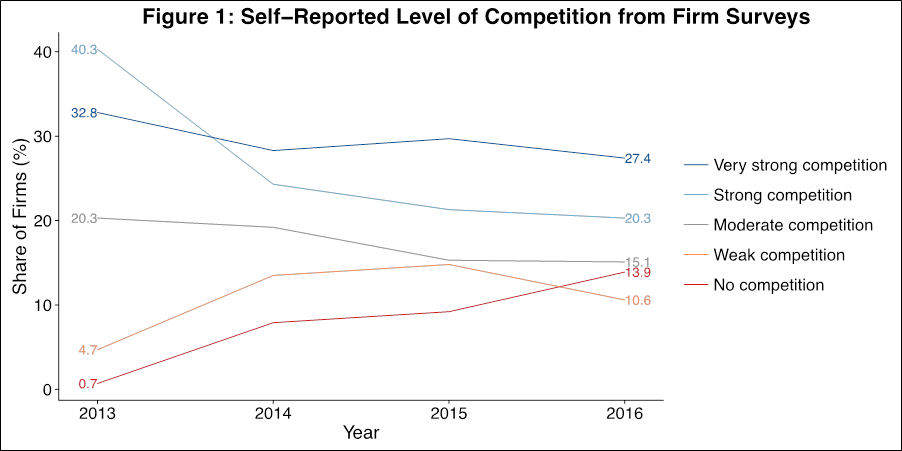

By several accounts, the state of competition in the Russian economy is not particularly healthy. Beginning in 2014, the Analytical Center for the Government of the Russian Federation has used surveys to track how firms perceive their competitive environment. Roughly 1,000 companies from 84 regions participate each year, answering questions about how competition has changed in their sector over the past year, as well as the steps they are taking to improve their own competitiveness. Interestingly, between 80-90 percent of firms surveyed are so-called microenterprises, with less than 100 employees. Whereas much of the anecdotal evidence of market consolidation derives from the so-called national champions dominating markets, the Analytical Center looks at a broader cut of the Russian economy. Figure 1 presents the distribution of responses (on a five-point scale) to the question: “How does your firm evaluate the current level of competition that it faces?”

A clear trend emerges. The share of firms responding that they face “no competition” has increased exponentially over the past four years, from 0.7 percent in 2013 to 13.9 percent in 2016. That statistic alone connotes an alarming rise in the number of markets where firms basically face no rivals to their profitability. In 2016, nearly a quarter of all firms report that they face either weak or non-existent competition, an increase of fivefold from just five years prior. Indicators of “very strong” and “strong” correspondingly fell during the period. Sectors such as information technology, food processing, and construction materials exhibit the greater internal competition, while firms working in lumber processing and energy provision face the least. These patterns are still ongoing: 24 percent of firms reported a drop in the number of direct competitors between 2015 and 2016.

Data: Analytical Center Competition Reports, 2014-2017

These survey results line up with other anecdotal evidence. In its 2016 annual report, the body tasked with preventing market consolidation, the Federal Antimonopoly Service, reported a growing number of politically connected cartels spread out in sectors across the economy, including defense, construction, and pharmaceuticals. These cartels coordinate and collude over winning state contracts (as highlighted by several investigations by Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation) as well as divide up markets and set prices. Consolidation has also occurred due to large companies swallowing up their rivals, often with little attention from regulators. Mergers and acquisitions are expected to continue unabated in the oil and gas, insurance and agricultural markets. As for the financial sector, the largest five banks in Russia collectively command over 50 percent of market share along a number of indicators.

What is Driving Market Consolidation?

The nearly continual state of economic crisis in Russia since 2008 has definitely contributed to consolidation in multiple sectors. Beyond macroeconomic effects (such as inflation, volatile currency exchange rates, and constricted budgets), economic crises can upend the playing field for firms competing in an economy. Crises often lead to greater market concentration by exposing and ultimately killing off firms with more variable access to capital, weaker political connections, and thinner margins. Bankruptcy rates in Russia shot up following both the 2008 and 2014 crises, while small- and medium-sized businesses felt the squeeze of skyrocketing interest rates, unsustainable tax burdens, and uncertain protection for their property rights. These crises helped clear the way for the larger firms with more solid financial footings to move in on their rivals.

But perhaps more importantly, economic crises further enable the leading factor behind weakening competition in Russia: greater government intervention and regulation of markets. In popular parlance, regulators are often associated with promoting equitable and fair competition by breaking up trusts and reviewing mergers and acquisitions for any anticompetitive fallout. But in Russia, the reality could not be more far off. In fact, a clear majority of firms surveyed by the Analytical Center throughout 2014 cite specific regulations introduced by government officials as well as uncertainty about the overall legislative base contributing most to the decline of competition in their markets. Firms view the Russian government as complicit in promoting anti-competitive behavior and placing pressure on companies in the market.

Competition-hurting policies come in many forms. During times of crisis, subsidies find their way to large, inefficient state-owned enterprises at risk of laying off workers and sparking political unrest. In addition, the Russian government has newly undertaken attempts to dabble in industrial policy and import substitution. By restricting imports of agricultural products (through counter-sanctions) and pharmaceuticals, the government is directly forcing foreign products and firms to exit the market. Finally, the state has forcefully reasserted itself as the largest owner of economic assets by nationalizing a number of important firms since the early 2000s. State-owned enterprises benefit from having their board of directors play dual roles in the public and private sector, including using administrative resources to undermine purely private sector rivals. This can matter particularly for access to finance, where state-owned banks now dominate, distributing more than 65 percent of retail loans and 71 percent of corporate loans in 2016.

In trying to combat these developments, the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS) may have bitten off more than it can chew. Besides taking responsibility for a whole host of functions such as monitoring public procurement and setting tariffs, the agency takes regulating market structure to the extreme local level, going after dairy producers in rural villages and individual entrepreneurs such as taxi drivers and salon owners. Nearly two-thirds of all companies on FAS’s register of companies with more than a 35 percent of market share are small- and medium-sized enterprises. FAS files over 60,000 anti-monopoly cases every year, by far the largest in the world (for comparison’s sake, the United States and European countries average around 100 per year). At the same time, FAS has refrained from going after the big guns of the economy that dominate their sectors (Gazprom, Sberbank, Rostex, etc.). FAS has the manpower and the legal instruments to enforce competition, but not the political independence from the top.

Domestic Political and Economic Implications

Decreasing competition can spur a whole host of economic and political challenges for a country. First, market consolidation can weigh heavily on economic growth. Companies that do not face competitive pressures invest less in innovation, labor productivity, and expansions into new markets. All three areas were weak points for Russia’s resource-dependent economy long before this latest surge in consolidation; decreasing competition will only make matters worse. The availability of easy monopoly profits incentivizes complacency and a preference for the status quo rather than economic progress. Monopolies look for ways to protect their gains rather than produce new openings. In addition, rampant corruption and rent-seeking are endemic to this fusing of the state and the economy. FAS recently calculated that the public sector already accounts for 70 percent of Russia’s GDP. Who will the state compete with when it owns nearly everything? Government officials prefer to work with state-owned, or at least politically connected, firms, while nimbler and efficient private firms lose out on access to finance and fairer regulations. Russia’s key modernization goals languish when monopolies dominate the economy.

Russian citizens also suffer from growing consolidation. Their pocketbooks already face a host of pressures stemming from high inflation and sharp cutbacks in welfare programs: add to these higher prices for lower-quality goods produced in consolidated markets. Giant monopolies also may contribute to greater income inequality as their outsized profits accrue only to the ownership class. Fewer firms operating mean worse job opportunities and lower wages; the private sector prefers a glut of excess labor which keeps its input costs low. The strongest job creators, small- and medium- sized enterprises, simple cannot compete with old market stalwarts that erect high barriers to entry. Consumers also become vulnerable to exploitation at the hands of big business, where collusion or other types of corporate crime often go hand-in-hand with oligopolistic market structures.

The more duress Russian voters face in their everyday lives, the increased likelihood that they will rescind their support for the regime. Protests over economic issues now completely outshine political ones, and opposition leaders are slowly but surely building campaigns to highlight declining welfare and rampant corruption. But the monopolization of the Russian economy also reduces the opportunities for other political forces to emerge and represent their interests. The Putin government has strived to achieve consensus among key economic elites by restricting the number of actors allowed to sit at the table. By preventing real competition between firms in important sectors of the economy, Putin has simplified governance problems. Dealing with an industry’s dominant and politically connected representative reduces negotiating frictions and facilitates the top-down coordination favored by Russian policymakers. Market consolidation ultimately impedes the emergence of actors with real resources who want to challenge the status quo.

Consequences for U.S. Policy

These structural changes in the Russian market must be taken into account when evaluating the effectiveness of international sanctions against Russia. Sanctions clearly lose some of their short-term bite when targeted Russian firms do not fear losing market share to their rivals. The resurgence of state ownership stakes also assures the new set of oligarchs connected to Putin that these firms are safe: the government will go to great lengths to protect them from international pressure. In many respects since 2014, the Kremlin has been building a protected wall around its national champions, funneling them subsidies, tax loopholes, and beneficial regulations in order to keep the main engines of the national economy afloat. The government seemed to realize that it would be harder for the West to drive a wedge between top elites if these individuals did not have to compete between themselves.

But the sanctions were specifically designed to inflict costs on the Russian economy that might not become evident for a decade. One example is the move to restrict dual-use technology imports; the Russian oil and gas industry can maintain output over the short-term, but ultimately will suffer greatly by not being able to exploit its more challenging deposits. The same is true of market consolidation. The Russian state-owned giants have weathered the first set of storms, but the greater levels of economic concentration spurred on by the crisis and government intervention will have a devastating impact on Russia’s ability to achieve sustained growth rates. Without reforms that unleash domestic competition and curb state intervention, stagnation is here to stay, which will ultimately weaken Russia’s ability to project power abroad.

David Szakonyi is Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University.

[PDF]