(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of the Donbas in 2014, the United States has committed over $1.5 billion in military aid to Ukraine. This past summer, the White House took special interest in the effectiveness of U.S. assistance to Kyiv, ordering a hold on a $391 million assistance package to Ukraine. Concerns with corruption and insufficient matching of funds by European allies were the expressed motivation for the hold. The aid was released on September 12 under Congressional pressure. President Donald Trump’s decision to withhold the aid is now the subject of a growing political scandal and has added to the ignition of a formal impeachment inquiry by the House of Representatives. Questions remain, however, about whether U.S. dollars have been well spent in Ukraine and how the U.S. government can improve returns on its military investments.

The largest issue with Washington’s assistance to Ukraine has been the lack of earnest engagement with the strategic questions involving Ukrainian defense reform, rather than corruption or matching contributions from European partners. A related problem is that the United States has not carried out a bona fide assessment of Ukraine’s progress in terms of the defense reform requirements. If history is any guide, the United States can only succeed in reforming a country’s foreign military when it becomes deeply involved in many aspects of the country’s military affairs, including its military doctrine, structure, professional military education (PME), procurement, and training. In addition, U.S. security assistance can be used as a leverage to push for systemic anti-corruption reforms.

Overview of U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine

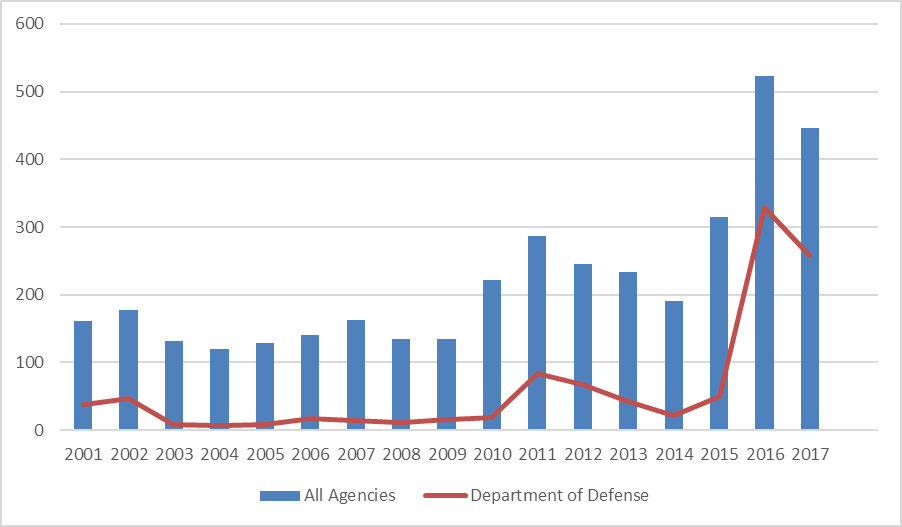

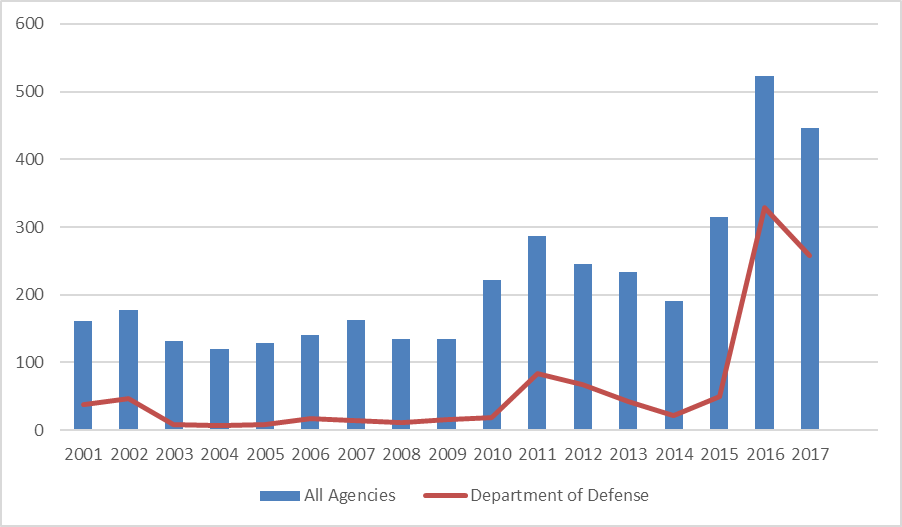

The United States has long supported Ukraine’s reforms and pro-Western orientation and has disbursed over $446 million in military and economic assistance since 2001. This makes Kyiv the largest recipient of U.S. aid in Europe and Eurasia. Until 2014, most of this assistance was channeled toward a wide range of governance reform efforts. Since 2014, security assistance funded and administered by the U.S. Department of Defense has constituted nearly 60 percent of total aid disbursed to Ukraine.

Figure 1. U.S. Foreign Aid to Ukraine (US$ million)

Note: Disbursements are the actual amounts of aid transferred by the U.S. government to Ukraine. Obligations, or binding agreements to disburse aid in the future, are typically higher. Source: USAID: Foreign Aid Explorer: The Official Record of U.S. Foreign Aid.

In a rare show of bipartisanship in 2014, the U.S. Congress approved the Ukraine Freedom Support Act, which affirmed U.S. support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military intervention in the Donbas region. The law directed the U.S. president to impose sanctions on several Russian entities and authorized him to provide Ukraine with defense articles, services, and training for countering Moscow’s offensive actions. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2016 established the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) for providing Kyiv with a range of defensive equipment and training. For both 2017 and 2018, the NDAA authorized funding to Ukraine in the amount of $350 million each year (although, not all of this aid has been disbursed at the time of writing), placing the country among the top ten recipients of U.S. security assistance in the world.

Most of the U.S. security assistance to Ukraine has been used for purchasing modern technology and much-needed defensive and medical articles and equipment (e.g., night vision goggles, radios, Humvees, body armor, and unmanned aerial vehicles). The second pillar of assistance has been military training. The United States and its allies established the Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine (JMTG-U) for providing training to Ukraine’s conventional and special operations forces at the Yavoriv training center in western Ukraine. U.S. personnel also advised their Ukrainian counterparts on various aspects of defense reform through the Defense Reform Advisory Board, the Doctrine Education Advisory Group, and the Defense Institution Building initiative, in addition to conducting the annual joint multinational land and sea exercises Rapid Trident and Sea Breeze.

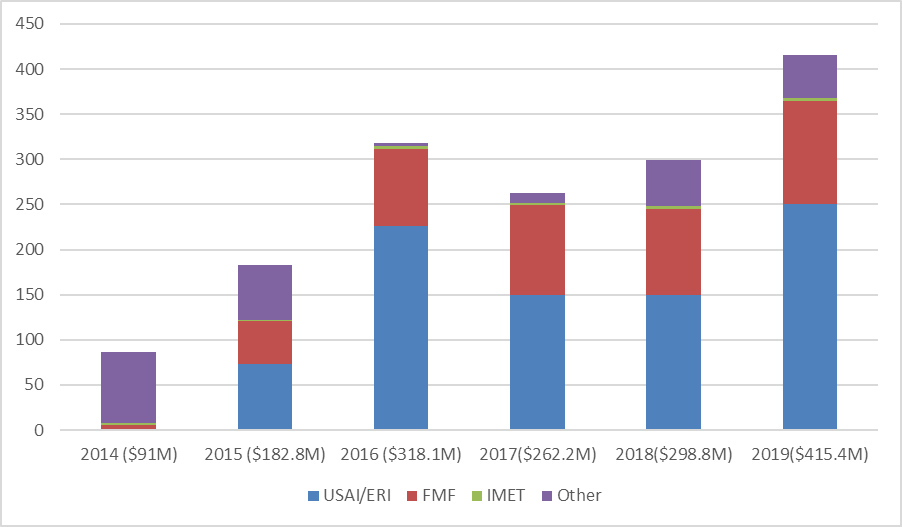

Figure 2. U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine (US$ million)

Note: USAI=Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative; ERI=European Reassurance Initiative; IMET=International Military Education and Training; Other=Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program, Cooperative Threat Reduction, International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement, Regional Centers for Security Studies, and other security assistance programs. Source: Security Assistance Monitor.

In December 2017, Washington approved the sale of Javelin anti-tank missiles to Kyiv. Although U.S.-made and other countries’ lethal weapons have been on the Ukrainian battlefield since 2015, the sale of Javelins marked a new era of the U.S. government supplying lethal aid to Kyiv directly. The NDAA of 2019 has codified this change into law by authorizing $50 million above the 2019 budget request of $200 million for USAI provided that the additional funds are used for lethal defensive equipment.

Ukraine and international observers concur that the state of the Ukrainian armed forces has considerably improved. The battle-hardened Ukrainian army is larger, better equipped and trained, and more capable of containing the advances of Moscow-backed separatists in the Donbas. It bears little resemblance to the poorly trained, under-equipped, demoralized, and divided army that suffered severe losses at the onset of conflict. Even though combat operations in the Donbas have unquestionably affected the army’s condition, the security assistance and training provided by the United States and foreign partners have contributed to the professionalization of Ukrainian officers and troops.

The Limits of U.S. Security Assistance to Kyiv

Despite the remarkable changes in Ukraine’s military forces since 2014, major problems in its defense sector remain. What has limited U.S. efforts at building Ukraine’s military capabilities is the lack of a long-term comprehensive strategy for American security assistance coupled with the Ukrainian leadership’s reluctance to engage in discussions of strategic questions regarding Ukraine’s defense reform. In the absence of a strategy and an implementation plan for developing its future military force, Ukraine has resorted to haphazard requests of short-term training programs by Western personnel and the provision of defensive and lethal aid to fight the war in the Donbas. The United States, in return, has focused on providing such training and equipment at the expense of developing a long-term strategic vision and implementation of meaningful defense reform. While the military hardware and training are important elements of Ukrainian defense, they are not enough to secure a retake of the Donbas or repel possible future Russian advances.

A related problem is that Washington has not been candid in assessing Kyiv’s progress with the defense reform requirements. The United States has put in place a certification process that makes the provision of appropriated security assistance conditional on meaningful actions in various sectors of Ukraine’s defense reform. Washington and its multinational partners have developed reasonable milestones and measures of success, but their application has become a matter of political expediency rather than a meaningful condition for aid disbursement.

The Ukrainian side has exploited this attitude by substituting mostly cosmetic changes for serious reforms. Thus, Ukraine’s strategic documents and the rhetoric of its leaders profess the country’s commitment to adopting NATO’s standards in every area of military performance by 2020. Building an army in NATO’s image may be an impractical option for Ukraine, but the activities have been supported with nominal substantive actions in furtherance of structural, institutional, and cultural reforms. For example, Stepan Poltorak, who had been the Minister of Defense of Ukraine in the rank of the General since 2014, retired in October 2018 to continue leading the agency (until May 2019) as a civilian in lieu of establishing de jure civilian control of the military. Further, the General Staff changed its designation to Joint Staff, leaving the structure and functions of the agency unchanged. Despite being the largest consumer of assistance under NATO’s Defense Education Enhancement Program (DEEP), Ukrainian PME remains a stronghold of old Soviet thinking and cadres reluctant to change curriculum, teaching approaches, and culture.

Even the system of tactical training prioritized in U.S. security aid has not been reformed. Hundreds of U.S. and foreign military personnel were discharged to the Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine (JMTG-U) for training Ukrainian forces and developing a cadre of Ukrainian trainers to assist the Ukrainian army in improving its institutional training capabilities. The Ukrainian leadership agreed to assuming the primary responsibility for training by 2022 in principle, but has not dedicated the necessary resources for taking over the program in practice. And, while the Ukrainian battalions that pass through the Yavoriv training center receive NATO interoperability certification, their proficiency in Western military standards is often short-lived. Ukrainian military personnel who receive training based on Western standards tend to get plugged back into their old units and sent to the frontlines of war, where they resume the old ways of conducting warfighting operations. These and other examples regarding military reform, PME, and tactical training transformation cast doubt on Ukraine’s seriousness about adopting NATO’s standards in a significant way. This is also a missed opportunity for the United States, which has allowed Kyiv to renege on commitments.

The United States is not the only partner assisting in reforming the Ukrainian armed forces. Kyiv has received significant assistance from at least eighteen other European and North American partners such as the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Norway, the Netherlands, Lithuania, and Poland. In addition, Ukraine has been the main recipient of funds under NATO’s Science for Peace and Security Program and the largest participant in the Alliance’s Defense Education Enhancement Program (DEEP). Yet, sufficient coordination of efforts among international partners has been lacking. In order to ensure that security assistance provided by the United States and other donors is effective in building a capable Ukrainian military force, they must consider doctrine development, institutional reform, and training and equipment integration.

Conclusions and Recommendations

To build a Ukrainian military with enduring and self-sustaining capacity for defending its sovereignty and territorial integrity, the United States needs to work closely with Ukrainian policymakers on developing a vision and strategy for sincerely reorganizing the Ukrainian military’s structure and institutions. If Ukraine is serious about adopting NATO standards for its military, it must work with the United States and similar international advisers in developing a realistic implementation plan that includes fundamental changes to Ukrainian PME, training, and procurement systems—under civilian oversight.

To put limited resources to effective use, the United States has to have a solid framework for assessment, monitoring, and evaluation of its security assistance program and hold their Ukrainian counterparts accountable for delivering meaningful results. The long-term comprehensive military education and training programs, which constitute less than one percent of American security assistance to Ukraine, need to be expanded because they carry the greater promise of long-term enduring changes to the values and mentality of the officer cadres studying at U.S. PME institutions. If the United States has the short-term, narrower goal of equipping Ukraine for success in the war in the Donbas, it needs to assist the Ukrainian military-industrial complex in modernizing its mechanized infantry combat vehicles (tanks) to adapt them for urban warfare. Supplies of counter-battery radars would be cheaper and more effective in reducing the damage from separatist artillery attacks than the largely symbolic and very expensive Javelin anti-tank missile systems.

Mariya Y. Omelicheva is Professor of National Security Strategy at the National War College of the National Defense University.

The views expressed in this memo are solely the author’s and do not represent an official position of the U.S. government or the National Defense University.

[PDF]

Homepage image (credit): “US delivers two AN/TPQ-36 radar systems to Ukraine, Nov. 14, 2015.”