(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Kazakhstan is known as one of the countries most loyal to Russia—even more so, in many respects, than Belarus. Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana) indulges Moscow less often than Minsk in rigorous bargaining games. Still, since the Ukraine crisis and the formation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), Kazakhstan has occasionally distanced itself from Russia, at least declaratively. The Kazakhstani government, more generally, maintains some measure of its longstanding, multivector foreign policy: open to all, but without denying Russia’s status as primus inter pares. But what about Kazakhstani public opinion? What do Kazakhstanis think of their northern neighbor, and why?

Central Asia Barometer (CAB) surveys conducted between 2017 and 2019, and ten focus groups conducted in 2019 (commissioned by one of the authors[i]) confirm that Kazakhstanis have positive views of Russia and of close ties between it and their own country. However, these positions are frequently moderate and non-exclusive of good relations with other countries, especially the United States and China, which suggests that they are the product not of the uncritical adoption of Russian narratives but rather of a pragmatic identification of Kazakhstan’s interests. Moreover, this pro-Russian attitude appears to be based less upon respect for, or fear of, Russia’s international power and assertiveness, and more upon a sense of shared history, perceptions of Russia’s present-day domestic accomplishments, belief that Russia’s international conduct is benign, and all of the practical and normative implications that such views entail.

Kazakhstanis’ Moderate Pro-Russian Position

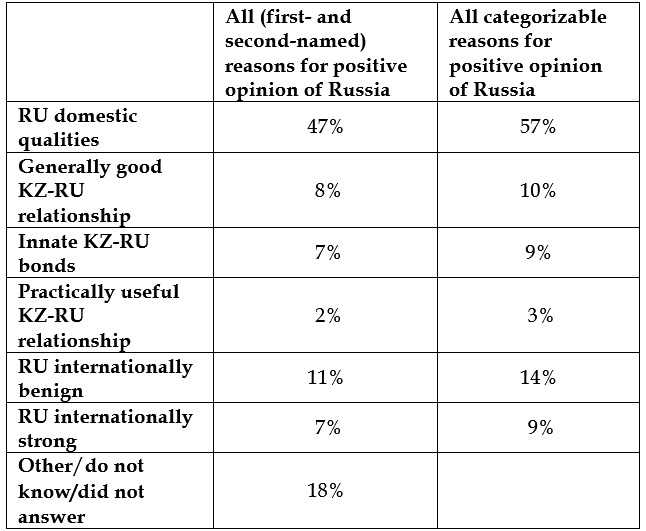

According to the CAB, Kazakhstanis overwhelmingly have a positive opinion of Russia and of close relations with it. Eighty-seven percent have a favorable view of Russia (vs. 8 percent unfavorable), 88 percent support closer relations with Russia (vs. 6 percent who do not), and 72 percent think that joining the Eurasian Economic Union has benefitted the Kazakhstani economy (vs. 14 percent who disagree).

However, for much of the Kazakhstani population, this pro-Russian position is best described as strong but not extreme. Moderate positivity toward the country, and toward relations with it, is at least as common as the maximally-positive options that are available in the CAB surveys, as can be seen in the distribution of answers to CAB questions about Russia and Russo-Kazakhstani relations in Table 1.

Furthermore, Kazakhstanis’ attitudes toward Russia are also moderate in the sense that they are accompanied by relatively positive and/or pragmatic attitudes toward other countries (including the United States and China) and toward relationships with them. That is, Kazakhstanis generally do not favor a Russia-only policy, even though they certainly lean toward Russia—and might opt for “Russia-only” if forced to choose between that and a similarly-extreme opposite alternative. For instance, of Kazakhstanis with a positive opinion of Russia, 55 percent have a positive opinion of the United States, and 71 percent of China. Similarly, of Kazakhstanis who favor closer economic relations with Russia, 59 percent also favor closer economic relations with the United States, and 65 percent favor closer economic relations with China.

Thus, public opinion certainly leans toward Russia, but not so much that relations with other countries are actively unwanted, suggesting a typical Kazakhstani position that is strongly but not extremely pro-Russian, and that sees value for Kazakhstan in relations with other countries, as well. This aligns with findings, which we have reported elsewhere, that Kazakhstanis’ opinions of various other countries, and of closer relations with them, are positively correlated (even when controlling for the opinion of Kazakhstani leadership)—even opinions of the United States and Russia. Kazakhstanis do not see a zero-sum geopolitical game between the United States and Russia in the region—a validation of the popular support for the country’s multivectoral philosophy.

What Kazakhstanis Value in Russia

Our other main finding is that Kazakhstanis are very positive toward Russia, but overwhelmingly for reasons not to do with its foreign policy. When it is because of its foreign policy, it is usually because that policy is seen as benevolent and peaceful rather than strong or resisting of the United States.

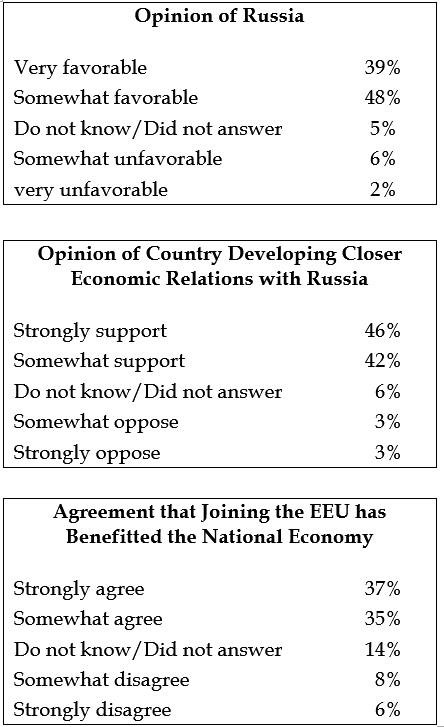

As mentioned above, the CAB surveys indicate that 89 percent of Kazakhstanis have a somewhat or very positive opinion of Russia. CAB also asks respondents to provide up to two reasons why they hold the opinion that they do, and 82 percent of the reasons provided by those with positive opinions can be categorized. (The other 18 percent were refusals or overly vague.)

Of those categorizable positions, 57 percent admire Russia’s domestic qualities, mostly its development in general or its economic growth in particular. Ten percent cite a positive Kazakhstani-Russian relationship, describing Russia as a friendly neighbor. Nine percent cite innate bonds with Russia, referencing either the history, culture, and mentality that it shares with Kazakhstan, or its perceived willingness to reunite the former Soviet states (implying a desire for such a reunion). And 3 percent cite the practical benefit of economic and business relations with Russia and membership in the EEU/Customs Union.

Only 9 percent, however, cite Russia’s strong international position, praising its role as “a significant ‘player’ in the world arena,” identifying it as “the only state that [can] resist [or] oppose the US,” or celebrating its “strong military.” In fact, a substantially more common reason for positivity, making up 14 percent of the total and constituting the final category, is praise for Russia’s benign role in global politics, celebrating either its “peaceful [policy]” or its involvement in “conflict resolution.” The full distribution of answers can be seen in Table 2 as follows. These views were corroborated by the focus groups (100 participants in total).

The admirability of Russia’s domestic (mainly economic and cultural) qualities was supported when participants were asked to identify two or three images that they spontaneously associated with Russia: almost none were negative. Participants evoked spatial or cultural features (wilderness, taiga, bears, the Hermitage, Leningrad, Moscow, music, literature, etc.), as well as Russian leaders, all with positive connotations. When asked if they considered Russia a more advanced and more European country than Kazakhstan, around two-thirds of the answers were in the affirmative. Participants celebrated Russia as abstractly more developed (“prodvinutaia,” “razvitaia”), and some sectors were explicitly named: Russia is said to have a better economy, technology, science, military, and space programs, as well as more advanced culture, sports, and welfare (pensions and maternal capital receiving frequent reference), not to mention more freedom of speech, civility, etc. The other third of answers were divided between those who held it impossible to compare the two cultures because they are too different, and those who said that Kazakhstan, while “remote” in some respects, had better, more “Oriental,” features than Russia, such as respect for family and elders, solidarity, hospitality, and less alcohol consumption.

Many participants also saw their country as closely bound to Russia. For instance, when discussion turned to the USSR, the majority of participants averred that all Soviet nations were brothers and sisters. Only a few accused the communist regime of major issues such as the planned destruction of the Kazakh nation, the loss of its language, collectivization, the exploitation of natural resources, and the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site. When asked about the Soviet Union in general, positive qualifiers dominated: it offered order, discipline, ideology, humanity, spirituality, free education and medicine, high-quality products, etc.

This discussion of the past was the only point featuring a substantial difference between the Kazakh- and Russian-speaking focus groups: the Kazakh-speaking ones conducted discussions of 19th century and Soviet history that were both more detailed and more polemical. Yet, although the Kazakh-speaking groups featured more criticism of Soviet-era cultural losses for the Kazakh nation—especially in language—they were still generally as pro-Russian as the Russian-speaking ones. This nuance was not captured in the surveys, confirming the added value of focus groups.

Contemporary cultural proximity to Russia was also evidenced: discussions of Soviet films, and of Russian celebrities, artists, and television series, were intense. When asked if they were nostalgic for the USSR and would like to return to it, almost all participants were explicitly against the idea, and very happy with an independent Kazakhstan. But a belief in the fundamental bonds between their country and Russia remains evidently widespread. And close relations with Russia were frequently seen as beneficial to Kazakhstan, which is not surprising given the widespread views that we have noted of Russia as a developed country that plays a benevolent or at least benign role on the international stage.

About three-quarters of participants declared that they see Russia as a partner, ally, and brother nation (bratskii narod) with whom relations are excellent. Some saw Russia as acting specifically as an older brother, not always treating Kazakhstan as an equal, but this was never a very sharp critique, and several participants even showed understanding. As one explained, “Yes, they have their imperial desires… that said, it’s understandable, and there is no threat in that” (Kazakh-speaking FG, Astana).

This view of Russia as relatively benign was paralleled in understandings of history. When asked about the 19th century addition of the Kazakh steppes to the Russian Empire, most participants held that the Kazakh hordes were attacked by Dzungars and needed the protection of Russia—the conventional historiographical interpretation, elaborated during Soviet times—even if most of those also placed this within a Russian realpolitik strategy of conquering the steppes. Still, many held that inclusion into the Empire had had complex results: loss of independence, and a threat to national language and religion, but improved access to education and technology.

Finally, participants also reflected the abovementioned view of Russia as a benign international actor in general, as well as a strategic ally to Kazakhstan in particular. Military partnership with Russia was particularly celebrated. Discussions of the dangers represented by China, and of Russia’s support for Kazakhstan’s sovereignty, were very consensual. Very few saw Russia as a potential danger to Kazakhstan, and none saw the Russian minority as a fifth column. Respondents also overwhelmingly agreed that Crimea is Russian and that it was natural for Russia to retake it. Several indicated that Ukraine was responsible for its own fate. Only about five participants expressed some doubts about the way the annexation was conducted, regretting the lack of a peaceful agreement with Ukraine or even labeling the action illegal.

Conclusion

Overall, Kazakhstanis have an understanding of their own interests and of the world that is relatively pro-Russian—but not blindly so, or altogether exclusively so, or as a result of some sort of highly-simplified and overly-biased narrative of contemporary international politics that is uncritically accepted from the north. On the contrary, it is based less upon respect for Russia’s international power or assertiveness, and more upon perceptions of shared history and fundamental bonds, of Russia’s present-day domestic accomplishments, of what they see as Russia’s benign international conduct, and of Kazakhstan’s own national interests.

While one cannot entirely rule out that respondents may have hidden their real views in front of pollsters or during a focus group, we observed several occasions where people freely expressed opinions that contradict state policies. One instance regards China, with public opinion being much more Sinophobic than the government’s. Another example concerns the Kazakh-Russian case, with the public expressing criticism of Russia’s colonial attitude while the governing regime remains shy on memory matters.

Interestingly, this globally pro-Russian attitude does not necessitate negative views of the United States, or opposition to having ties with the United States. Nonetheless, Kazakhstanis are generally sympathetic toward Russia’s foreign policy and, in cases of Russo-U.S. tensions, they largely take the Russian side. Gallup surveys that we have cited elsewhere reported that, in 2014, an overwhelming majority of Kazakhstanis (72 percent) prioritized relations with Russia over those with the United States (vs. 7 percent who held the opposite opinion). Furthermore, our focus group participants overwhelmingly took Russia’s side in its conflict with the United States, praising its recovery and defense of its own interests.

The surveys and focus groups suggest that Kazakhstan’s multivector policy, with Russia as primus inter pares, is largely supported by Kazakhstani public opinion. Oversimplifying Kazakhstan’s posture as that of a dominated country, brainwashed by Russian propaganda, does not fit the reality of a Kazakhstani public whose views of its northern neighbor are more complex, mixed, pragmatic, and deeply-rooted than Western observers often believe.

Marlene Laruelle is Research Professor, Director of the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES), Director of the Central Asia Program, and Co-director of PONARS Eurasia at the Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University.

Dylan Royce is a PhD student and Research Assistant at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES) at the Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University.

This article is part of a project with Eric McGlinchey, on Russian, Chinese, Militant, and Ideologically Extremist Messaging Effects on United States Favorability Perceptions in Central Asia, funded by the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory under the Minerva Research Initiative, award W911-NF-17-1-0028. The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory.

[i] Ten focus groups were commissioned by Marlene Laruelle and conducted by Serik Beyssembayev and his team at the Strategiya Sociological Center. Each had 10 participants (for a total of 100). Focus groups in Almaty and Astana were conducted in Russian and Kazakh; those in Shymkent, Kyzylorda, and Aktau only in Kazakh; and those in Karaganda, Petropavlovsk, and Ust-Kamenogorsk only in Russian. The questions were drafted by Marlene Laruelle and Serik Beyssembayev in Russian, and translated by the latter into Kazakh; the data from all the Kazakh-language focus groups were subsequently translated into Russian. Each focus group contained an equal number of men and women, and a representation of age groups and professional sectors—with the exception of rural-dwellers, as the survey were done in urban settings.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 658 (PDF)

Table 1. Kazakhstani Attitudes toward Russia and Relations with It (CAB)

Table 2. Reasons for Kazakhstanis’ Positive Opinions of Russia (CAB)