(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) In 2010, thirteen of Russia’s ethnic republics had their own presidencies. Today, the Republic of Tatarstan is the only region to retain the institution, despite a federal law that requires that regional leaders not contain the word “president” in their titles. For several years, both the Kremlin and the Tatarstan authorities have carefully depoliticized the issue and avoided overt criticism of one another. Nevertheless, a bill sent to the Russian parliament on September 27 looks set to change this, prompting Russia’s ethnic republics to navigate and balance two increasingly antagonistic positions: as mobilizers of strong electoral results for the government and as defenders of the rights of Russia’s ethnic groups.

The Regional Factor in Russian Politics

Under President Vladimir Putin, it has become temptingly easy to overlook the regional factor in Russian politics. After all, compared to the surge of ethno-nationalist mobilization in the 1980s and early 1990s, Russia’s ethnic republics have been remarkably quiet since Putin took office in late 1999. As a result, regionalism fell off the scholarly agenda as researchers recalibrated to instead ask how the federal center was able to bring the regions to heel so quickly and with such little resistance.

The conventional wisdom to emerge is that several of Russia’s ethnic republics established a strong “power vertical” several years before Putin managed to do the same. Russia’s regional elites used their considerable administrative resources to provide electoral windfalls for Putin in exchange for being able to maintain a degree of sub-national autonomy. This account appears to hold water: looking at the latest parliamentary elections on September 9, the top 10 subjects by turnout were ethnic republics, which also produced 8 of the 10 highest vote percentages for United Russia (both among single-member districts and party-lists).

Center-region relations have, however, been more complicated than a straightforward quid-pro-quo arrangement that electoral results alone might suggest. Instead, they can be best understood as part of a long-term process of bargaining. Whereas in the 1990s, regional leaders used the threat of ethno-nationalism to extract concessions from the federal center, more recently, they have used their mobilizational and managerial capabilities as bargaining chips with a now much stronger federal center. Indeed, many of the initial federal reforms under Putin—such as the reform of the upper chamber of Russia’s legislative body in 2000 and establishment of presidential envoys to the newly-created federal districts—intended to strengthen the center’s position vis-à-vis the regions by limiting governors’ influence over central policy and increasing central oversight over the regions.

An important but often overlooked part of this ongoing bargaining process has involved Russia’s regions pursuing legitimation strategies and symbolic politics to build a support base among their populations. While many of Russia’s ethnic republics set up authoritarian political machines, some—notably Tatarstan and Bashkortostan—also invested heavily in social programs to buttress support. At the same time, regional elites were able to diffuse the threat from ethnic nationalists by adopting many of their demands, whether through ambitious education and language programs, patronage of nationalist intelligentsia and cultural institutions, or by creating state symbols and engaging in “state-like” behavior in the international arena. In many cases, these patterns differed little from the nation-building practices taking place in other independent post-Soviet states.

Russia’s Regional Presidencies

Regional presidencies are a distinctive feature of Russia’s political landscape, tracing their origins to the perestroikaera.[1] Mikhail Gorbachev established the position of “President of the USSR” in March 1990, which spurred union republic leaders to follow suit to bargain on equal terms with the center. Meanwhile, nationalist movements within Soviet Russia sought more autonomy for their regions through being “upgraded” to union republic status.[2] Once it became clear that the center was unwilling to alter the existing administrative hierarchy, Tatarstan set about organizing its own presidential elections, and its leader, Mintimer Shaimiev, was elected president of Tatarstan on June 12, the same day Boris Yeltsin was elected president of Russia. As the Soviet Union unraveled in late 1991, other regions established presidencies of their own. This pattern was not universal, however; some republics institutionalized the post later, such as Udmurtia in 2000 and Dagestan in 2006, whereas others created and then later amended the title, such as Tuva in 2002, and Kalmykia and North Ossetia in 2005.

The challenge to Russia’s regional presidencies came from one of its most eminent strongman leaders, Chechnya’s Ramzan Kadyrov, who renounced the title in August 2010, claiming that there should only be one official with the title of “president” in Russia. This spurred nationwide discussions over the issue, and in December 2010, the parliament adopted, in the third reading, a bill that would give regions until January 1, 2015, to ensure that their executives’ titles did not contain the word “president.”

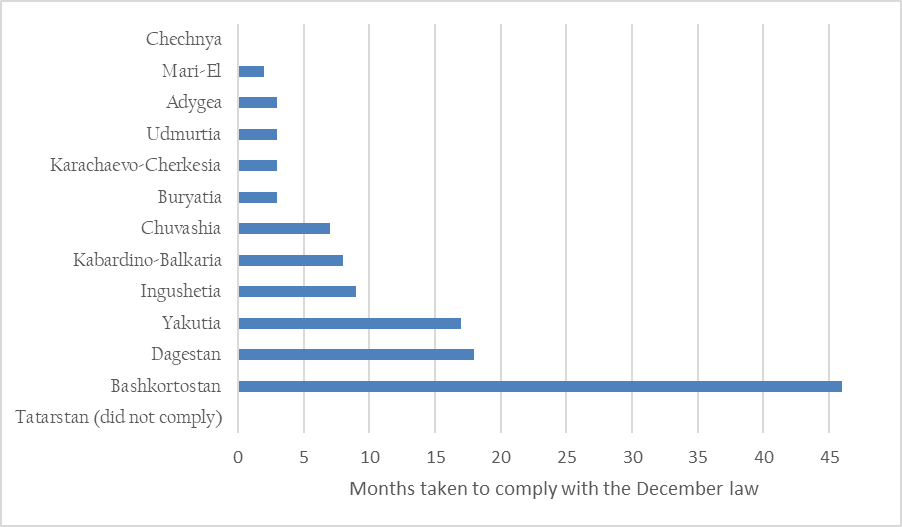

As Figure 1 shows, Tatarstan was the only region not to comply before January 2015. Most regions had formally adopted local amendments well before the January 2015 deadline. The heads of Mari-El and Udmurtia had signaled that they would do so almost immediately following Kadyrov’s August 2010 statement. Bashkortostan and Tatarstan were initially quite dismissive of the law, claiming that they had plenty of time to make any necessary changes, with the former removing the title of “president” just one week before the deadline, leaving just Tatarstan.

Figure 1: Regions Adopting Local Amendments by the 2015 Deadline

Careful Depoliticization

As of January 1, 2015, Tatarstan’s presidency contradicted federal law. Nevertheless, the delicacy with which the issue of non-compliance has been navigated by both the Kremlin and Tatarstan’s elite shows an unusual degree of hesitancy.

In February 2015, an amendment was made to the law that pushed back the deadline— only applicable to Tatarstan—to January 1, 2016. As I described in a recent journal article, during this time, there was no overt contestation from either Moscow or Kazan. It is plausible that bargaining was at play here given that Tatarstan had a gubernatorial election in September 2015: the incumbent president of Tatarstan (and member of United Russia), Rustam Minnikhanov, was elected with 94 percent of the vote, a result that the republic’s top brass wasted little time in using to emphasize the legitimacy of the presidency itself. When asked about the title in his annual press conference in December, Putin dismissed the issue, saying that it was up to the people of Tatarstan to decide. Once more, as of January 1, 2016, Tatarstan’s presidency contradicted federal law, and once more, it remained uncontested. Speculation arose in the run-up to the following gubernatorial election in 2020, but the federal center again turned a blind eye to the issue.

Since 2020, however, there have been growing signals that changes are on the horizon. The amendments to the Russian Constitution in 2020 will require regional constitutions to be amended accordingly, although Farid Mukhametshin, chairman of Tatarstan’s State Council, stated in December 2020 that Tatarstan would not raise the issue of the presidency. Then, in January 2021, a letter was published from the local prosecutor’s office claiming that the title was in violation of federal law.

On September 27, 2021, a bill was proposed in the parliament that, for the first time, elaborated upon the notion of a “unified system of public power” that featured in the 2020 amendments. On the one hand, it offers a “carrot” by proposing to do away with the existing requirement that leaders serve no more than two consecutive terms, benefitting long-time regional leaders such as Minnikhanov and Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin. On the other hand, it also contains a potential “stick” by requiring that all regional leaders be named “head” (glava), which once more raised the issue of Tatarstan’s presidency.

Once again, public commentary was initially conspicuously absent. Minnikhanov’s annual address to Tatarstan’s State Council on October 8 steered clear of any mention of the issue. Yet, on October 25, Tatarstan’s State Council unanimously declared its objection to the proposed bill, displaying an unusual degree of official contestation. By presenting a unified front in opposing the bill, Tatarstan’s authorities sent a strong signal to the federal center that departs from previous practice whilst remaining consistent with the logic of bargaining.

An Increasingly Narrow Tightrope

The possible elimination of Tatarstan’s presidency signals the tail-end of a decades-long process of centralization. It also throws into relief the tension between mobilizing strong electoral results for the government and being able to promote ethnic group rights and shore up local legitimacy.

This tension was, until recently, quite mild. As late as 2016, Tatarstan’s elites could still point to the region’s ambitious Tatar-language education policy and bilateral power-sharing treaty with the federal center as important achievements. In 2017, however, minority language education was unexpectedly challenged—Tatar language classes went from being mandatory and taught for up to six hours a week to being an optional subject capped at two hours a week—and the bilateral treaty was left by Moscow to expire. As I suggest, given that Tatarstan was focused on lobbying for an extension to the bilateral treaty, the assault on language education came as a genuine shock—such that it took Minnikhanov almost three months to comment upon it publicly.

Yet, the general lack of overt contestation by Tatarstan’s elites should not be misinterpreted as a sign that language and identity issues ceased to matter. As argued by Guzel Yusupova in a previous policy memo, ethnicity is becoming an increasingly powerful social identity as bottom-up practices and symbols spread. In these conditions, the institution of the presidency has acquired additional potency because it is the last remaining symbol of Tatarstan’s claim to statehood. The 1552 conquest of Kazan and the destruction of the Khanate of Kazan by Ivan the Terrible remains for many reasons one of the most important unifying elements in Tatar historical memory (as one historian put it, no less important than the Mongol invasion for Russians), but also serves to underscore Tatars’ history of independent statehood—something that was central to activists’ demands for union status in the perestroikaera. These debates remain no less relevant in contemporary Russia, especially as official policy shifts to carve out a privileged space for ethnic Russians: a case in point is the amended Article 68 of the Constitution in 2020, which adds that Russian is the “language of the state-forming people” (gosudarstvoobrazuyushchii narod).

Conclusion

The Kremlin and Tatarstan’s authorities were able to skillfully depoliticize the thorny, legal, political, and even cultural issue of Russia’s last remaining regional president for quite some time. Nevertheless, the recent introduction of a bill on the “unified system of public power” in the parliament seems to herald the end chapter to Russia’s regional presidencies. Minnikhanov might be able to remain in power indefinitely but no longer as the “President of Tatarstan.”

As the last remaining symbol of Tatarstan’s claim to statehood, the abolition of the presidency highlights the increasing tension between mobilizing pro-government votes on the one hand, and defending ethnic group rights on the other. Centralization—especially since 2017—has, however, rendered regional leaders’ claims as defenders of ethnic group rights increasingly hollow. Returning to the logic of bargaining, central to the regions’ role in contemporary Russian politics is their ability to pursue local legitimation strategies and engage in symbolic politics to shore up support. Analysts should pay close attention to how leaders in Russia’s ethnic republics navigate this amidst conditions of centralization.

Adam Lenton is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at George Washington University.

[1] Sub-national presidencies do exist elsewhere in various forms, such as Ethiopia and Somalia. Belgium uses the title Minister-President. In Spain, the institution is officially “president of the government” of the region.

[2] Autonomous republics were nested within union republics and had fewer benefits. For instance, according to the 1977 Soviet Constitution (Chapter 15, Article 110) whereas union republics sent 32 representatives to the upper chamber of the Supreme Soviet, autonomous republics sent 11. Most key competencies, including budgetary decisions, were held by the union republics in which the autonomous republics were located.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 719