(PONARS Policy Memo) Pundits continue to debate whether economic shocks, public discontent at home, and isolation abroad will shake President Vladimir Putin’s regime. Much of the commentary on Putin’s survival strategies has focused on repression and aggressive military posturing. This somewhat obscures another important strategy: being highly sensitive to the public mood, deftly reacting to public sentiment, and effecting rapid policy shifts to moderate public dissent.

Manipulating how mass media covers popular protest is central to this strategy, but it would be a mistake to assume that such coverage is uniformly negative. Instead, Russian media coverage of mass protest shifts dramatically between attempts to undermine public support for anti-regime activism and efforts to pander to the public mood driving such activism, depending on changes in public sentiment and developments on the ground. In making this case below, I draw on findings from new research into how Kremlin-controlled media portrayed the 2011-12 protests in Russia and the protests in Ukraine that preceded the Euromaidan revolution in late 2013.

Kremlin-Controlled Media and Russian Domestic Protests

A longstanding tradition in research on social movements distinguishes between two different ways protest can be “framed” or interpreted for media consumers: (1) the “disorder” frame; and (2) the “freedom to protest” frame. The former treats protest as an instance of undesirable chaos whereas the latter characterizes it as a legitimate and even desirable expression of public sentiment. Coverage can employ different mixes of both frames.

Which of these frames did Russian media employ for the protests that broke out in late 2011 against falsification in the December 2011 parliamentary elections? In Figure 1, news stories were coded as a scale, from full usage of the disorder frame to full invocation of the freedom to protest frame. Higher values indicate more use of the freedom to protest frame while lower values reflect greater employment of the disorder frame for a given day between October 2011 and December 2013.[1] As seen below, there are major fluctuations in how the Kremlin-controlled media covered protest in Russia during this period.

Figure 1. “Framing Scores” of News Articles (Russian domestic protest)

Looking more closely at Figure 1, each little gray dot represents a framing score for an individual article published by the Russian media. Higher scores indicate that popular protests were framed as freedom to protest, while lower scores indicate that they were framed as social disorder. The curves represent average scores at respective time points, showing overall trends in how street protests were framed over the period. (These average scores are statistical estimates, which inevitably include a certain degree of error, but they fall within the range indicated by the dotted curves with 95 percent confidence.)

There are four spikes in the overall quantity of news stories about protest, each indicated by a vertical dotted line labeled S1-S4. The trend line connecting these spikes clearly shows a shift toward the freedom to protest frame between S1, the onset of mass protests in December 2011, and S2, the May 2012 Bolotnaya Square mass anti-regime protests, which featured skirmishes between protesters and police that triggered an unprecedented wave of repression against the political opposition. S2 also coincides with Putin’s inauguration for a third presidential term.

At this point, however, a sharp drop occurs toward the disorder frame as we approach the third spike in media coverage of protest (S3). During this period, media stories were overwhelmingly concerned with “exposing” and “preventing” alleged plots of another mass uprising, ostensibly supported by agents of former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili and his Western backers abroad. This can be referred to as “fabricating protest,” whereby the media deliberately planted misinformation into the public domain about the threats protests pose to public order. Following S3, there is a gradual upward shift in the direction of the freedom to protest frame roughly until the fourth spike in protest coverage is reached; this is S4, the October 2013 Biryulyovo anti-migrant riots in Moscow.

After this period, however, there is not a significant dip in the direction of the disorder frame. This is despite the fact that the Biryulyovo disturbances featured traits that would fit the disorder narrative well. These include vandalism, right-wing extremist slogans, and public expressions of xenophobia and racism. The work of Christopher Hutchings and Vera Tolz, who have analyzed nationalist discourses on Russian television for an earlier time period, helps shed light on these findings. They observe that beginning in 2012, the leading state-controlled channels intensified narratives stigmatizing non-Russian migrants and ethnic and religious minority groups, thereby pandering to exclusive forms of Russian nationalism. This observation is in line with arguments that the Kremlin adapted nationalist rhetoric following the regime’s realization of the unlikely alliance between nationalists and political liberals during the 2011-2012 mass protests.

Kremlin-Controlled Media—Protests in Ukraine

The tactic of stigmatizing anti-regime political protests while tacitly endorsing expressions of Russian nationalist sentiments is replicated in the Russian government-controlled media’s coverage of Ukraine’s Euromaidan protests. To analyze Russia’s responses to the Ukraine crisis, the study compares and contrasts coverage of the Euromaidan by Kremlin-controlled media with coverage by various non-Kremlin-controlled media, namely the news agencies Interfax and Rosbalt along with Zerkalo nedeli (Mirror Weekly, one of Ukraine’s leading independent news sources that appears in Russian).

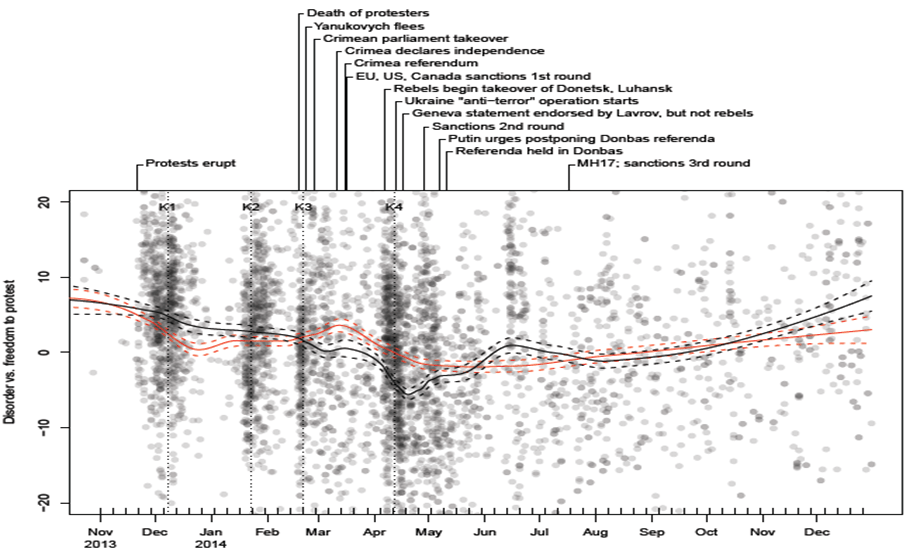

Figure 2 summarizes the trends in the Russian state-controlled media’s portrayal of the Euromaidan-related events. Here, the average framing of Kremlin media is represented by a red line (based on the dots representing individual news articles), and the average framing of the independent media is captured by the black line. In order to make better sense of shifts in Russia’s media coverage of protests in Ukraine, Figure 2 also presents a timeline of key events during the first pivotal months of the crisis alongside the trend lines of fluctuations in Russian media’s protest framing.

A significant deviation of the Kremlin’s frame from the frames employed by non-Kremlin media toward the protests-as-disorder narrative (that is, a major separation of the red from the black lines) is observed only after the fall of the former President Viktor Yanukovych government and his flight from Kiev in February 2014. In fact, the framing of protests by state-controlled sources and independent media tended to be in line with each other until mid-February 2014. Only at that point, did framing of protests in Russia’s state-controlled media become more negative and significantly different from that of the non-Kremlin controlled media. This trend lasted until May 2014.

Figure 2. Framing of Protests in Ukraine by Different Media

Why did Kremlin-controlled media framing deviate significantly from that of independent media only for this short period? The study gained leverage on this question by performing a series of simple key-word searches to identify trends in vocabulary alluding to the plight of ethnic Russians in Ukraine. Figure 3 summarizes these findings. In this chart, following Yanukovych’s departure and coinciding with the annexation of Crimea, Russia’s state-controlled media began to employ legalistic jargon about “federalization,” “referendum,” and the status of the Russian language and of ethnic Russians (russkie) frequently in ways differing from coverage by sources not under the Kremlin’s control.

However, the Kremlin promptly abandons these strategies by the end of April. This coincides with its disastrous failure to replicate the relatively peaceful Crimea annexation scenario in the Donbas. By many accounts, there was a significant minority of residents in Donestsk and Luhansk regions whose sentiments favored joining Russia. Yet, public opinion surveys revealed that the overwhelming majority there—let alone in the other territories that Russia briefly referred to as Novorossiya, namely Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya, Kherson, and Mykolayiv—showed a preference for an undivided Ukraine.[2] Furthermore, in Russia too, an influx of migrants into regions bordering Ukraine and war casualties served to dampen the public euphoria surrounding Crimea’s annexation.

The Kremlin media’s abandonment of these key terms may also be explained by the fact that protests also began to appear within Russia, demanding the “federalization,” or outright secession, of Siberian and other regions within Russia itself. These demands represented the Russian political opposition’s thinly veiled references to the Kremlin’s hypocrisy inherent in fomenting separatist sentiment abroad while depriving Russia’s own regions of meaningful decision-making powers.

Figure 3. Frequency of five keywords until the end of 2014 (coverage of protests in Ukraine)

Conclusion

Kremlin-controlled media have adeptly altered the coverage of public discontent at home and abroad in ways meant to undermine dissent, or, alternatively, cater to public sentiment thereby increasing citizen support for the Putin regime. Rather than being witness to a grand strategy, tactical shifts implemented, abandoned, or altered rapidly as events unfolded. These trends in the framing of protests indicate that media analysis could be a useful tool for exploring shifts in Russia’s domestic and foreign policy. For policymakers seeking to unpack the black box of the Kremlin’s decision-making, media analysis may represent an important way of revealing shifting intentions and tactics. It may also help ascertain not just the sources of regime strength, but also its weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

Tomila Lankina is Associate Professor at The London School of Economics and Political Science.

The information presented and arguments made are based on in-depth analysis of media data using a methodological tool developed with my research colleagues at The London School of Economics and Political Science. I would like to thank in particular Kohei Watanabe for performing the media analysis part of the study; Katerina Tertytchnaya for her help with Russian protest data analysis; and Yulia Netesova for her assistance with analyzing Russian and Ukrainian media sources. All errors are solely those of the author.

This research relied on the Integrum database of Russian media to harvest news stories on protests by employing the search term “protest” (“протест”). The stories were obtained from six leading state-owned or state-controlled media sources Rossiyskaya gazeta, Komsomolskaya pravda, and Izvestiya, and the television channels Channel 1, Russia 1, and NTV. We obtained 28,531 news stories in total for the period between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2013. They include TV transcripts, newspaper articles, and newswire reports. With the help of these stories, we developed a Russian-language dictionary of media framing of protest. The dictionary-generation process involved human coding of news by three native Russian-speakers to capture the tone of media coverage of street rallies. It also involved a machine analysis component—the computer program that we created can “learn” from human coders what scores to assign to words found in thousands of media stories on protest. For the analysis of non-Kremlin-controlled media under protests in Ukraine, we did a similar analysis of stories on protest in Russia. We downloaded TV transcripts, newspaper articles and newswire reports from the Integrum Russian news database by employing the search term “protest*” (“протест”). A geographic classifier that we developed helped ensure that only stories of protests in Ukraine downloaded. The total number of news stories harvested for the period November 1, 2013 to December 31, 2014 is 22,568.

For more details, please see the project website: popularmobilization.net

[1] See the Appendix for methodology, sources, and link to the project website.

[2] See, for example: Mikhail Alexseev, “War and Sociopolitical Identities in Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 392, October 2015 and Henry E. Hale, Nadiya Kravets, and Olga Onuch, “Can Federalism Unite Ukraine in a Peace Deal?,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 379, August 2015;