Since independence, many post-Soviet states have witnessed a rise in religious tension, particularly between the predominant Orthodox churches, other faiths, and the secular requirements of modern governance. In Georgia, the bonds between the Georgian Orthodox Church and the state are longstanding and deep-seated. For centuries, the Church has played a pivotal role in the national identity of the country: in society, culture, economics, and politics.

As Georgia moves toward greater association with the EU, however, there have been some shifts in church-state relations that have challenged principles of secularism and Westernization. They have raised questions of tolerance and, in the context of contemporary geopolitics, the implications of the relationship between the Kremlin, the Moscow Patriarchate, and the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Church and State—Indivisible?

The Georgian constitution guarantees equal protection of the liberties and rights of citizens regardless of their ethnic or religious affiliation. However, there are fewer divides between church and state in Georgia than in many democracies. Critics argue that the Patriarchate is the only institution in Georgia to demonstratively disobey secular legislation and that it improperly interferes in civil affairs.

Indeed, the Georgian constitution recognizes the “special role of the Apostle Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia in the history of Georgia,” thus acknowledging its status as the country’s most popular and powerful spiritual institution. Opinion polls consistently demonstrate high public trust in the Church and in Ilia II, who has been Patriarch since 1977 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Confidence in Georgian Institutions (%)

Source: IRI, Georgia National Study, Georgia, February 2014

The reach of the Georgian Church into the social fabric was boosted even more by a 2002 concordat (a year before former President Eduard Shevardnadze was ousted by the Rose Revolution). The concordat granted the Georgian Church privileges such as tax exemptions, special consultative roles in the government (particularly in education), immunity for the Patriarch, and military exemptions for clergymen. The Church also has a line item in the government budget (it received $14.2 million in 2013).

Until 2011, all other religious denominations (e.g., Baptists, Roman Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and Armenian Apostolic Christians) had to register as “organizations” rather than as religious communities. The 2011 reform was promoted by the EU and applauded by the West, but the Georgian Church saw it as an infringement of its unique status.

Because the Church is a powerful symbol of the country’s sovereignty and an important part of the Georgian national narrative and consciousness, the stance of the Church on moral, ideological, and political issues carries significant weight.

Accordingly, officials from the Church have inserted themselves into national political debates on the Georgian economy, culture, domestic issues, and foreign affairs. Likewise, Georgian political elites have used religion as a tool for voter mobilization. Politicians refrain from criticizing the Church and its policies because its authority and reach make it a strong potential ally.

A Rise in Strife?

Rather alarmingly, and significant because of its dominance, the Church has been increasingly linked to narrow nationalist causes. Some of its followers, even clergymen, have been implicated in attacks on other faiths and minorities.[1] Radical elements from within the Church were allegedly behind a violent group called the Union of Orthodox Christian Parents, which orchestrated fistfights and other unlawful actions against minority groups in 2010 and 2012.

In May 2013, a half year into Bidzina Ivanishvili’s new administration, the growing sway of fundamentalist and nationalist elements was on full display during a rally for the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia (IDAHOT), when thousands of people, clergymen among them, took to the streets and attacked a small rally of some fifty activists. The confrontational tone changed when the Church denounced and distanced itself from the violence. However, it did not go unnoticed that the Patriarch called on authorities the day before the rally to ban it as an “insult” to Georgian traditions. After the violence, authorities condemned the aggression as a “shameful act” and promised to punish those involved, while the Church called on both sides to pray for each other. In the end, trials of the clergymen involved did not result in sentencing. Two of the most aggressive were only suspended from their duties for a period of time (in fact, they were sent to a monastery until they confessed their errors).

In August 2013, authorities removed a newly-installed mosque minaret in the village of Chela after local Orthodox clergy objected to its presence. This focused attention on the uneasy coexistence between the Orthodox Church and the country’s Muslim population, which equals almost 10 percent of the population.[2] In response, the Georgian Patriarchy accused outside forces of provoking confrontation between Christians and Muslims in order to discredit the church and state.

The Curious State of Georgia-Russia Church Relations during the 2008 Conflict

The 2008 war provided unique insight into Georgian-Russian Church relations. In spite of the severe political tensions between Tbilisi and Moscow, relations between the Russian and Georgian Orthodox Churches remained cordial. The two churches tend to side with their national governments, but the Russian Orthodox Church diverged from the Russian state—a rarity—when both churches cooperated to offer relief to civilians. The Georgian Patriarch made a pastoral visit to the conflict zone via its active links to the Russian Patriarchate, bringing food and aid, even as the land was occupied by Russian troops.

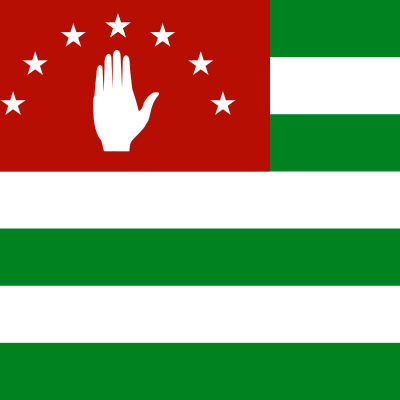

After the conflict, the Russian Church declined to accept the recognition of South Ossetia or Abkhazia as independent entities (counter Kremlin policy). The Russian Holy Synod passed a resolution officially recognizing the Georgian Orthodox Church’s jurisdiction over the dioceses in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Some say the move by the Russian Church was actually a pragmatic move meant to forestall the Georgian Orthodox Church’s recognition of the independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Whatever the reason, the Georgian Church appreciated the Russian Orthodox Church’s respect for its canonical borders. However, in a further twist, in September 2009, the Abkhazian Orthodox Church declared “independence” from the Georgian Orthodox Church.

A Conservative Pan-Orthodox Front?

Today’s resurgent post-Soviet Russia has re-embraced Orthodoxy as its national faith in order to promote its imperial ambitions—leading some commentators to believe that Moscow is playing to the Georgian clergy, even to the Patriarch himself, to reject Westernization. Indeed, many forces within the Georgian Church establishment have been long skeptical toward the liberal democratic West. Georgian clergymen have openly linked the EU with the destruction of values, the erosion of national traditions, and the promotion of homosexuality—saying they undermine Georgia’s national traditions and spiritual mission.

The Georgian Orthodox Church holds great moral authority among voters, and it is not unthinkable that the Kremlin would seek to exploit this. One sign of this was in mid-January 2013, on the occasion of Ilia II’s 80th birthday and his 35-year anniversary as Patriarch, when Putin conveyed the following wishes on his website:

“We appreciate your warm attitude towards Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church. Your personal efforts, and calls for peace, love, creation, harmony and unity largely contributed to the preservation of centuries-old ties of friendship and understanding between our peoples in a complex stage of history.”[3]

In late January 2013, Patriarch Ilia II went on a 6-day visit to Moscow during which he received an award from the Russian Orthodox Church’s International Foundation for the Unity of Orthodox Christian Nations (IFUOCN). After he met with Putin, the Patriarch said:

[Putin is a] “a very wise man [who] will do everything to ensure Russia and Georgia remain brothers, and the love between the countries will be eternal….In the past Russia and Georgia were like brothers, but apparently someone envied this, and artificially created hostility between us.”[4]

While it is not clear what will ultimately result from the Kremlin’s rapprochement with the Georgian Orthodox Church, it is conceivable that the embrace of anti-Western rhetoric by Georgian Church members could negatively influence national public opinion and, hence, the country’s foreign policy aspirations.

2014: The Latest Developments

For now, the Church professes to stay the course. After a March 2014 meeting with EU Commissioner for Enlargement and European Neighborhood Policy Stefan Fule, the Patriarch complained of the misperception that the Georgian Church seeks to hinder Georgia’s Europeanization. Responding to Fule’s public statement that the EU has no intention of undermining Georgia’s traditional values, Ilia II said,

“I’ve learned from the media that you said you would assure the Patriarch that Georgia can become a member with its traditions, values…. I want to tell you that I am convinced of that for a long time already…. The European Union is an organization, which is well known by the Georgian people. We will do everything to make Georgia a full-fledged member of this large organization.[5]”

But then in April 2014, the reactionary nature of the Church was revealed when it publicly contested a new anti-discrimination parliamentary bill, which was needed for the country to move ahead in its Visa Liberalization Action Plan with the EU. The bill provides protection against a range of discrimination (including for gender orientation), but the Patriarchate asked for the bill to be postponed “to secure engagement of the Church and broader public in its discussion,” with the reason being:

“Proceeding from God’s commandments, believers consider non-traditional sexual relations to be a deadly sin, and rightly so, and the anti-discrimination bill in its present form is considered to be a propaganda and legalization of this sin.”[6]

Conclusion

Orthodoxy is one of the most conservative forces in post-Soviet Eurasia. It tends to view any innovation as a foreign threat aimed at destroying sacred national traditions. Occasional friction between Georgia’s pro-Western political elites and the Georgian Orthodox Church is not unusual. However, because it is the most respected institution in Georgian society, certain Church actions and statements can cause problems for Georgia’s European prospects. Many observers of regional politics believe that Orthodoxy and social conservatism are two areas that Russia can exploit to frighten Georgia away from Europe. There is also a risk that some Georgian clergymen may be vulnerable to Kremlin soft power approaches. This may negatively influence public opinion, which still strongly supports Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration.

It is the job of the Georgian government to apply, through the proper constitutional mechanisms, a constructive approach to Church-state relations without alienating this powerful institution. The Georgian Church can potentially play an important role in fostering tolerant and non-violent efforts to unite different parts of Georgian society. Together, these two Georgian institutions could yet be a powerful force for progress.

[1] “IRI Georgian Poll Finds Increased Confidence In Parliament And Media,” May 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.iri.org/news-events-press-center/news/iri-georgian-poll-finds-increased-confidence-parliament-and-media

[2] “The results of the 2002 population census of Georgia,” National Statistics Office of Georgia, Vol. 1, 2003. Available at: http://www.geostat.ge/cms/site_images/_files/georgian/census/2002/I%20tomi%20-%20saqarTvelos%20mosaxleobis%202002%20wlis%20pirveli%20erovnuli%20sayovelTao%20aRweris%20Sedegebi.pdf

[3] See “Katolikosu-Patriarkhi vseia Gruzii Ilii II.” Available at: http://kremlin.ru/letters/17319

[4] “Patriarkha Gruzii obvinili v dukhovnoi izmene rodine. Soratnikam Mikhail Saakashvili ne ponravilsia visit Ilii II v Moskvu,” Kommersant, January 29, 2013. Available at: http://www.portal-credo.ru/site/print.php?act=news&id=98246

[5] See http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=27008 and http://theorthodoxchurch.info/blog/news/2014/03/patriarch-church-will-do-everything-to-make-georgia-eu-member/