(PONARS Eurasia Commentary) The failure to stop Russian President Vladimir Putin’s accumulation of power made possible his invasion of Ukraine. If Russian society hopes to prevent future tragedies, ordinary citizens need to actively stand up to the authorities in order to prevent the kinds of abuses that Russia is now inflicting on Ukrainian society.

Leaders accumulate as much power as they can until they meet resistance. This law of politics works in both democratic and authoritarian systems. The main difference between the two is the presence of checks and balances. Limiting executive authority is the main job of the legislature and courts. Among the post-Soviet states, leaders in Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, and Belarus have constantly worked to put down any opposition to their rule. Only in Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and Armenia have societies managed to create some limits. Kyrgyzstan is an exception where social ferment has now resulted in the criminalization of power with unknown consequences.

Unfortunately, Russian society has never shown an ability to check the authority of its government, which systematically disregards human rights. In this situation, it is up to the international community to aid Russian society in restraining Kremlin powers.

Putin’s Elimination of Checks and Balances

Although Russians suffered terrible economic deprivation during the 1990s, they inherited from the Soviet Union an increasingly pluralistic and vibrant press, relaxed controls on the freedom of assembly, and a profusion of new political parties and non-profit organizations. However, this period was more of an anomaly than the beginning of real citizenship in their own country.

Putin built up a strong security service and police apparatus with salaries paid by the Kremlin. With this institutionalized set of loyal enforcers, Putin has moved against any individual, group, or institution he thinks might try to circumscribe his power. During the first part of his rule, some citizens stood up against state policies in an effort to protect the environment, preserve the culture of their cities, fight corruption, and numerous other causes. But the government systematically labeled disliked groups as “foreign agents” and “undesirables.” As Russia entered into war this year, the lack of independent media and subservient courts made it impossible for Russians to speak truthfully about the violence.

Those Who Left and Those Who Remain

Russia’s history and authoritarian structure are not unique, nor are the problems its citizens face. In fact, its model of government might simply be called “banal bullying.” Something similar is apparent in Kenneth Branaugh’s recent film depicting how ordinary people dealt with the rise of extremists in Belfast.

Over the years, many of Russia’s most outspoken advocates for a different policy and form of government have left the country, either of their own choices or fearing imminent arrest. The recent acceleration of brain drain from Russia means that its most active citizens now invest their talents in new countries. Those who stay behind typically remain silent to avoid becoming a victim of their own government.

The exodus of the most active members of society disrupts the nascent social networks developing to support an alternative to the bullying regime. Such networks are crucial for putting together active protests that actually set Russia on a different path from Putinism. However, with every émigré, the likelihood of such protests drops; Putin understands this and leaves the borders open, sacrificing the future of Russia.

Thousands of Russian scholars and students have signed statements denouncing the cruel barbarism of the Russian military, as have numerous other groups. But the rectors of Russian universities, presumably the leaders of the intellectual elite, signed a statement supporting Putin.

A Few Solidary Heroes

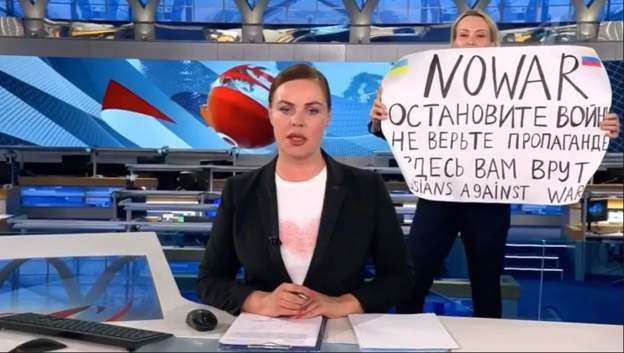

Marina Ovsyannikova, a Channel-1 television employee who grabbed headlines by protesting on the “Vremya” news show (image above), is one of a handful of prominent protesters in Russia today. Facing the widest audience possible in the country, she called on the Russian people to come to the streets, declaring, “only we can stop the madness … they can’t jail us all.” More than 14,000 Russians have been arrested protesting the war. However, these actions demonstrate a strong reserve of resistance to the Russian leader.

A Brewing Crisis and Intensifying Sanctions

Putin’s crackdown on Russia’s free society has been building since he took office, slowly but inexorably. The Orange Revolution of 2004 shook the president and led him to accelerate his efforts to control Russian society, with the protests of 2011-12 again boosting his clampdowns. It reached its most recent crescendo on March 16, 2022, when he called Russians who protested the war “scum and traitors.” On the same day, President Joe Biden publicly referred to Putin as a “war criminal.”

The West is imposing massive sanctions on Russia’s leaders, Kremlin enablers, oligarchs, military suppliers, energy system, foreign currency assets, and a variety of its educational, sporting, and cultural institutions. From the energy giants to MacDonald’s and IKEA, Western companies have left the country. The purpose of the sanctions is not to facilitate such a process but to weaken Russia as much as possible so that it presents less of a danger to the world. In this sense, the sanctions are rational and necessary.

Scenarios for Russia’s Civil Society after Putin

A major question is: what will Russian society look like after the war reaches some kind of conclusion? The international community will need to address this because Russia, distressed and with a full nuclear arsenal, will be a problem for everyone. There are a number of possible scenarios.

The most optimistic possibility is one in which the Ukrainian forces can inflict sufficient losses on the Russian military so that it is no longer an effective fighting unit. At the time of writing, Ukrainian soldiers managed to push Russian troops away from Kharkiv. Russia has taken significant losses. Such a catastrophic price in human suffering could theoretically destabilize the Russian political system and lead to Putin’s removal.

Many observers say as long as Putin remains in power, it is extremely unlikely that the majority of Russians will turn against their government. One key issue is that once aging Putin is gone, it is not clear who will replace him. There is no legitimate successor, and even Putin’s own rule is based on the result of fraudulent elections that were manipulated in advance. Moreover, the office of the Russian vice president was abolished in 1993.

If Putin is gone, there will be an opening for society to revive. This would be a difficult process since Russians would have to come to terms with their country’s war crimes. Until now, the leadership has often referred to the victory over Nazi Germany in World War II as Russia’s greatest accomplishment. Despite the murderous Stalinist regime, Russia has been able to present itself as a victim of the Nazis. Now, Russia is the aggressor state, and it will face atonement, probably similar to how Western societies have attempted to come to grips with the slaughter of Indigenous groups in the New World and slavery.

Another scenario is Russia waging a battle against an indefinite insurgency, keeping Putin in power as a wartime chieftain following Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s model of semi-militant control that indefinitely suppresses all opposition. With Putin running a war of attrition in Ukraine and facing bleak economic prospects at home, he will stifle demonstrations. Ostensibly, he will imprison and kill enough people to send a strong message that people should be supportive or silent and passive. With Russia increasingly isolated and impoverished, a dangerous situation is stirring.

The Case for International Action

In his speech to the U.S. Congress, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky called for creating “U24 United for Peace,” which he described as a union of responsible countries that have the strength and consciousness to stop conflict within 24 hours. In these conditions, isolationism is not an option. The United States will have to work with its democratic allies to thwart Russian aggression while ensuring that it does not collapse the way that Germany did in the early part of the twentieth century. The international community will have to be actively involved in attempting to communicate with Moscow to ensure that Russia does not descend into the kind of meltdown that could unleash nuclear Armageddon. At the same time, the West will need to confront the countries that support Russia. The absence of a vocal and vibrant Russian opposition makes all these jobs extraordinarily difficult.