(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) For the new countries that emerged after the collapse of the USSR, few tasks have been more important, or challenging, than building institutions of government that enjoy public trust. While the frenzy of institution-building in the newly independent states breathed new life into the study of institutional trust, there has been little published research focused on Central Asia. This memo aims to advance our understanding of trust in government in two Central Asian societies with divergent economic and political trajectories. Resource-poor Kyrgyzstan has seen little economic growth, has gone through two violent regime changes, and is the first and only Central Asian country to hold an election judged as largely free and fair by international observers. Things could hardly be more different in Kazakhstan, with its abundant natural resource wealth and a president who has been in power since the fall of the Soviet Union.

The juxtaposition of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan allows us to shed light on the influence of divergent economic and political trajectories on institutional trust and its determinants. Our comparison reveals much higher levels of trust in Kazakhstan than in Kyrgyzstan. Although Astana’s attempts at economic diversification have yet to produce meaningful results, the country’s vast natural resource wealth propelled considerable economic growth which, in turn, appears to have bolstered overall levels of institutional trust. Our research also shows that the dissimilar political and economic trajectories of the two societies have not only generated different levels of institutional trust but also profoundly altered the effects of several individual-level determinants of trust.

Data

We use nationally representative data collected in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in late 2012 to compare levels of institutional trust in the two countries and to identify individual-level predictors of trust. Our questionnaire covers a broad range of socio-political and economic topics that reflect theoretical and empirical debates in sociology, political science, and area studies. Fifteen hundred face-to-face interviews with respondents aged 18 and older were completed in each country, with a response rate of 89 percent in Kyrgyzstan and 60 percent in Kazakhstan. In both countries, multistage stratified probability samples of households were utilized.

Levels of Institutional Trust in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan

In this section, we present the results of our country comparison. We examine trust in the following institutions: regional government, national government, president, parliament, army, judicial/legal system, and police. Respondents were asked: “Please tell me how much do you personally trust [name of institution]?” The response options consisted of: “1) definitely distrust,” “2) somewhat distrust,” “3) somewhat trust,” and “4) definitely trust.” The resulting frequency distributions are presented in Table 1.

For every institution included in our analysis, respondents in Kazakhstan are significantly less critical than their counterparts in Kyrgyzstan. The institutional trust gap between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan ranges from the lows of 4.5 percent (trust in police) and 7 percent (trust in the judicial/legal system) to the highs of 26 percent (trust in national government) and 30 percent (trust in the president), respectively. Interestingly, in both countries, people have the lowest levels of trust toward the two institutions they are most likely to encounter in their daily lives: the judicial/legal system and the police. Yet, it is the basic pattern of consistently higher institutional trust levels in Kazakhstan in comparison with Kyrgyzstan that we find to be most striking.

Previous studies conducted in post-Soviet societies note that relatively higher levels of trust in the president may reflect trust in a particular person rather than the office of the presidency. The same logic could be at work in Kazakhstan, since it has one of the longest-serving presidents in the world and has never experienced a free and fair election. And yet, while it is true that President Nursultan Nazarbayev has an outsized presence in Kazakhstan’s political landscape, the roughly 30 percent trust gap between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan is not entirely inconsistent with results for several other political institutions. The reported 83 percent trust in national government and the 79 percent trust in parliament exceed the equivalent results from Kyrgyzstan by 26.2 percent and 26.3 percent, respectively.

It appears that the two societies’ divergent economic and political trajectories have generated substantially different levels of institutional trust. Kazakhstan’s remarkable resource wealth fueled economic growth, helped preserve the political status quo, and bolstered trust in institutions. In contrast, economic difficulties and political volatility in Kyrgyzstan appear to have taken a toll on institutional trust in the resource-poor country. The exceedingly high levels of political trust found in Kazakhstan resemble the findings from China by Zhengxu Wang at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China who found that economic development and increased affluence have boosted trust in institutions. By the same token, the pattern of lower levels of institutional trust found in Kyrgyzstan is consistent with results (2002) by William Mishler (University of Arizona) and Richard Rose (University of Strathclyde) from other post-Soviet economies that experienced prolonged decline and stagnation.

The one similarity that persisted in both countries, despite this divergence, is the pattern of significantly lower levels of trust in the judicial system and the police—the two institutions that regular people are more likely to have direct experiences with in comparison with any of the other institutions in our analysis. However, even in the case of these two institutions, respondents in Kazakhstan appear to be more trusting than their counterparts in Kyrgyzstan.

Determinants of Institutional Trust in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan

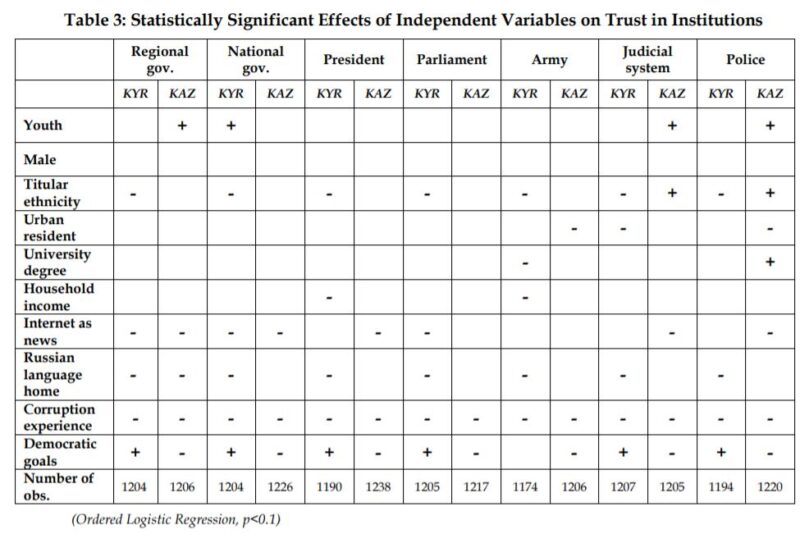

We have already established that the divergent economic and political trajectories of the two societies have produced very different levels of institutional trust. But do these country-level differences suggest that individual-level determinants of trust are also dissimilar? In the next section, we present findings from multivariate regressions used to identify individual-level determinants of institutional trust in the two societies. We examine the effects of age, gender, ethnicity, area of residence, education, household income, internet use, being a Russian language speaker, personal experience with corruption, and support for democratic political goals (see Table 2).[1]

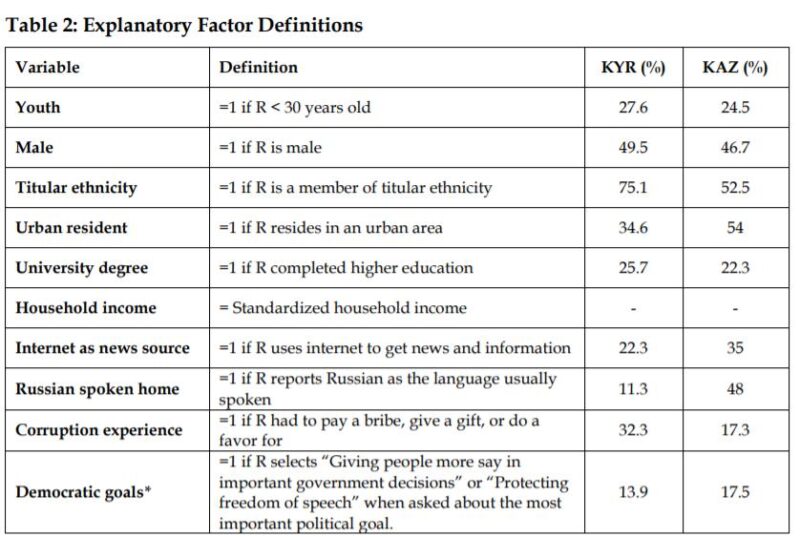

Our analysis shows that the dissimilar political and economic trajectories of the two societies not only generated different levels of institutional trust but also altered the effects of various individual-level determinants of trust (see Table 3). Some of the most interesting results are summarized here. Young people in Kazakhstan displayed higher levels of trust in comparison with those who are older. Yet this effect was largely absent in Kyrgyzstan. While membership in the titular ethnic group had a uniformly negative effect on institutional trust in Kyrgyzstan, this was not the case in Kazakhstan, where Kazakhs actually displayed higher levels of trust in the judicial system and police. Interestingly, gender had no discernible effect on trust in any institution in either country.

In both societies, regular use of the internet as a source of news and information is associated with lower levels of trust in the regional and the national government. In Kazakhstan, it is also associated with less trust in the president, the judicial system, and the police, while in Kyrgyzstan those who regularly get their news from the internet are less likely to trust parliament. This result is consistent with research carried out in China by Min Tang at Shanghai University and Narisong Huhe at University of Strathclyde that showed that the Internet can undermine the support basis of an undemocratic regime. In Kyrgyzstan, those who reported Russian as the main language spoken at home had lower levels of trust for every institution included in this study, but this effect was largely absent in Kazakhstan. Personal experience with corruption is the only factor in our analysis that appears to be immune to the country-level differences. Those who had to deal with corrupt officials in the preceding year were uniformly less trusting of institutions than those who did not. Finally, we were struck by the very different effect of democratic values on institutional trust. In Kyrgyzstan, where the 2010 presidential election was judged to be largely free and fair, those who espouse democratic values reported higher levels of institutional trust, perhaps giving the newly established institutions the benefit of the doubt. However, in the significantly more authoritarian Kazakhstan, people who prioritized democratic political values were more skeptical about the institutions of government.

Conclusion

While it is undoubtedly true that institutional trust is essential for effective governance, it is equally true, according to Mishler and Rose, that “excessive trust cultivates political apathy and encourages a loss of citizen vigilance.” The uniformly higher levels of institutional trust found in Kazakhstan mean that it is more governable than Kyrgyzstan. However, this pattern also produces political stagnation. To wit, the extraordinarily high level of public trust enjoyed by Kazakhstan’s long-time leader has clearly stifled the development of genuinely competitive political culture. The political apathy and the complete absence of healthy political contestation ought to be a cause for concern for the resource-rich country whose leader turns 80 years old in the summer of 2020. Therefore, in important ways, the pattern of trust found in Kazakhstan appears to be more problematic than the one we discovered in Kyrgyzstan and does not bode well for the prospects of political modernization in the vast country at the heart of Eurasia.

Azamat Junisbai is Associate Professor of Sociology and Barbara Junisbai is Assistant Professor of Organizational Studies at Pitzer College.

[1] The correlation between the assessment of institutional performance and institutional trust is well documented and not particularly intriguing. People everywhere are more likely to trust the institutions they think highly of and distrust the institutions they find to be problematic. We believe that our focus on the other factors has the potential to provide more intriguing, and less obvious, insights.

*Operationalization for the “Democratic goals” variable is informed by the understanding that the term democracy can mean different things to different people. Therefore, we avoid the explicit use of the term “democracy” when measuring support for democratic values. Instead, we use the standard question about the “most important political goal” and assign the value of “1” to respondents who selected “Giving people more say in important government decisions” or “Protecting freedom of speech” and a value of “0” to everyone else.