A recent Radio Free Liberty report tells the story of two young anti-war activists, Adelya and Ivan from Nizhnekamsk (Tatarstan), who fled Russia after being intimidated and threatened with criminal charges. They are not alone. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, similar experiences have led more than 1.3 million citizens to abandon their home country.

Previous research underscores that the international community’s failure to support Russian migrants has shifted the burden of support to individual host countries and communities. Accordingly, this memo asks: How can host societies support Russia’s wartime migrants to enable successful life transitions and build a foundation for sustained activism? In this memo, we rely on survey and interview data to explore migrants’ needs in their own voices. While most of our respondents strive to be self-sufficient, they face several obstacles, including uncertainty regarding their ability to stay in host countries, economic struggles (issues with finding/keeping jobs, trouble transferring funds, lack of savings, etc.), fears about personal safety, and mental health challenges. These obstacles limit their capacity to engage in activism, self-help, community-building, and other collective activities. To help, we propose a series of policy recommendations, including opening Western countries to some Russian migration; job fairs; language and personal-safety training; and online mental health support.

We rely on two types of data: an extensive interview project with more than 450 informants and two waves of a survey conducted by the OutRush team. The informants for the interview portion of our study were recruited from the OutRush online panel and via chain referral with different seeds in local Telegram self-help channels and personal networks.

Distinctions within Migrant Communities

Migration from Russia on political grounds began long before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. As Vladimir Putin gradually “tightened the screws” in the 2010s, many political activists, especially LGBTQ activists, migrated to escape the threat of prosecution. Migration accelerated following the annexation of Crimea. Finally, after Aleksei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation and its regional networks were labeled an “extremist organization” in June 2021, many Navalny activists and independent journalists also left the country. These groups constituted the vanguard of wartime migration.

The post-February 2022 war-induced migration (members of which are sometimes dubbed “Februarists”) began in the spring and summer of 2022. Approximately 200,000 people left Russia for Armenia, Georgia, Turkey, Serbia, and a variety of European destinations. The next wave (“Septembrists”) was triggered by the “partial mobilization” in September 2022 and comprised another 600,000 or so people, many of whom chose visa-free Central Asian countries like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. In total, about one million of the Russians who had left remained abroad in 2023, although estimates vary widely.

This large-scale migration provoked a discussion within the migrant community about how to refer to themselves. This process of identity-building included bridging terms like “relocants” (mostly applied to employees of large companies who had secured remote employment), “diaspora” (used specifically to describe those who had already settled somewhere), “refugees” (who constitute only a small fraction of the total), “exiles,” and “migrants.” This debate over language highlights the substantial differences among groups, defined by the timing, motivations, and conditions of their emigration. For migrants, this debate represents the first hurdle: transcending differences to forge a common community based on a shared identity, purpose, and understanding of shared challenges—and thus enable collective action.

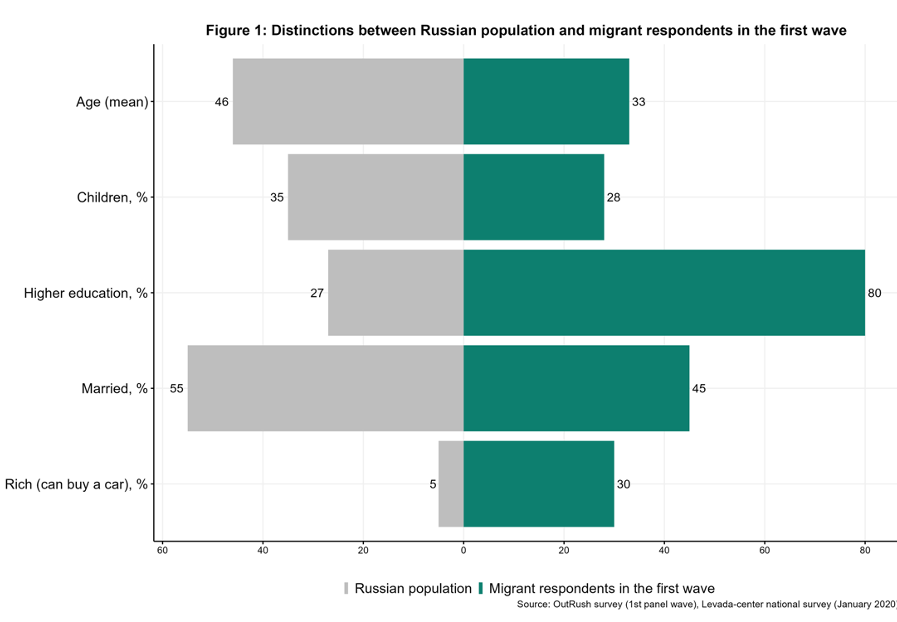

Distinctions in wealth also meant that individual migrants have faced different challenges. While members of the Russian diaspora who left during the first wave tended to be wealthier and better educated than the Russian population (see Figure 1), individuals’ resources varied widely prior to leaving Russia and continued to diverge after migration. Some were in-demand professionals, such as a risk manager from Moscow who graduated from a prestigious private university. Others worked for international companies that provided relocation packages or allowed remote work. Many migrants had portable skills but no path to immediate employment. As a respondent from the movie industry recalled: “We didn’t have much savings. We had a business, but we had to leave it and run away” (male, Canada, July 24, 2023). Meanwhile, many younger migrants lacked material resources or job prospects.

In addition to illustrating the profile of migrants relative to the Russian population, the data reported in Figure 1 support the characterization of the Russian wartime exodus as a brain drain that has significant consequences for key sectors: higher education, IT, and business.

Host Country Dynamics

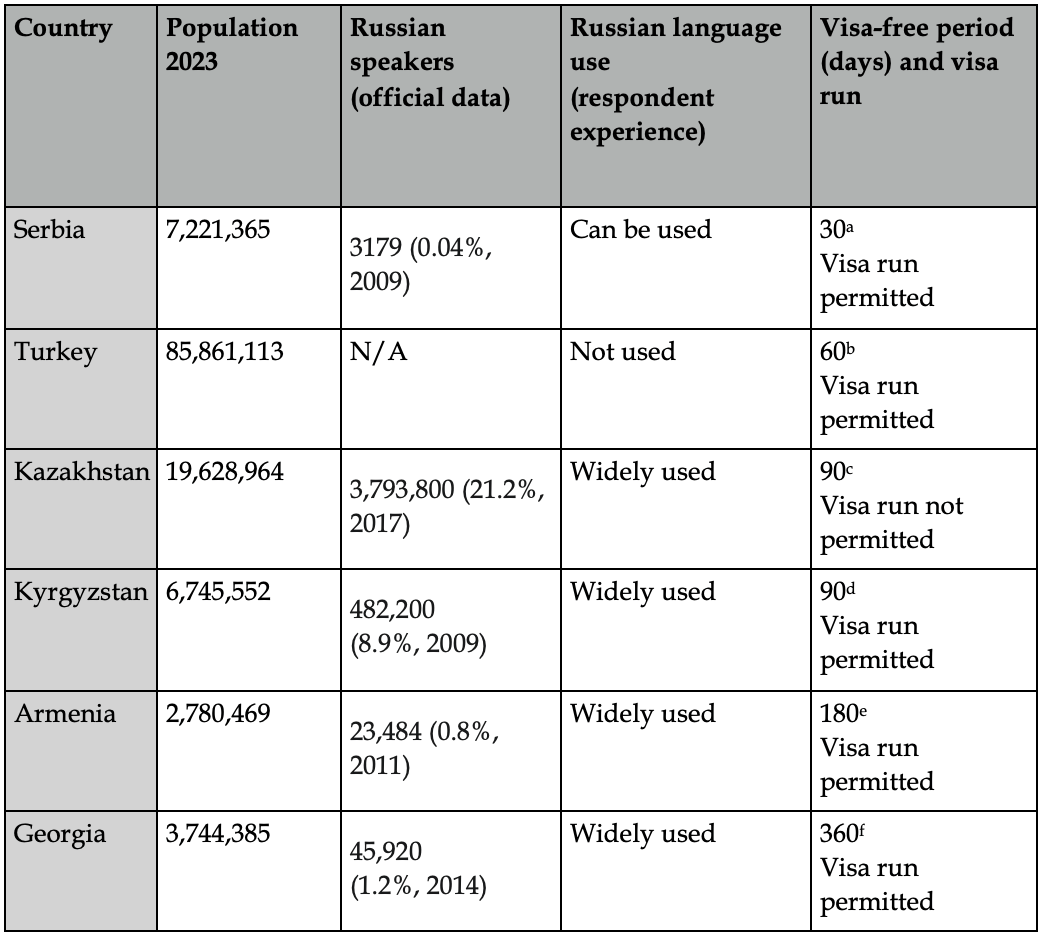

The conditions in which wartime migrants find themselves vary widely across host countries. These conditions shape individuals’ opportunities and resources to work collaboratively to support the transnational community of Russian migrants. Table 1 captures some of the main features of the host countries in our case study: the population of the host country, the size of the existing Russian-speaking community, rules governing the use of the Russian language, and residency regulations (including the length of the visa-free period).

Table 1 underscores that official numbers of Russian-speakers notwithstanding, respondents find that Russian is widely used in all host countries except for Serbia and Turkey. Many migrants speak some English, but learning the national languages of their host countries poses a challenge. Typically, they learn some colloquial words and phrases for everyday interactions and offer a choice between Russian and English for more complex conversations. Only respondents in Turkey reported difficulties in finding a common language. In Georgia, for example, the public authorities are known to interact in English, while in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, Russian is widely used in government offices.

ahttps://www.relocate.world/en/articles/residence-permit-Serbia

bhttps://visaguide.world/europe/turkey-visa/residence-permit/

chttps://egov.kz/cms/en/articles/vid_na_jitelstvo

dhttps://grs.gov.kg/ru/subord/drnags/information_for_foreigners/

ehttps://www.mfa.am/en/residency/

fhttps://migration.commission.ge/index.php?article_id=161&clang=1#:~:text=To%20obtain%20fa%20residence%20permit,the%20Public%20Service%20development%20agency%3A

The data in Table 1 also illustrate the variations in the complexity of host-country residency requirements, which are constantly changing. Initially in Kazakhstan, it was relatively easy to get a temporary residency permit (TRP), which allowed one to stay in the country for up to one year. A TRP permit can be obtained by opening an individual enterprise or acquiring an employment contract. Georgia has the longest visa-free period, at 360 days, while Serbia offers only 30 days (albeit with a relatively easy visa run). Our interview data show that few informants have permanently settled in their host country. For most, moving between countries has been inevitable, increasing frustration and uncertainty.

Migrants’ uncertainty has only been augmented as host countries have responded to new waves of immigration—and citizens’ discontent—by changing their visa regulations. In January 2023, Kazakhstan introduced a new 90/180 rule, which permits Russians to stay in the country for 90 days within a 180-day period without registration, taking away the option of a visa run. The interview data reveal that maintaining legal status is a significant challenge for respondents. Even if some countries are visa-free, the process of obtaining work or residence permits or certifying education or professional documents is often cumbersome, limiting migrants’ opportunities to establish residency.

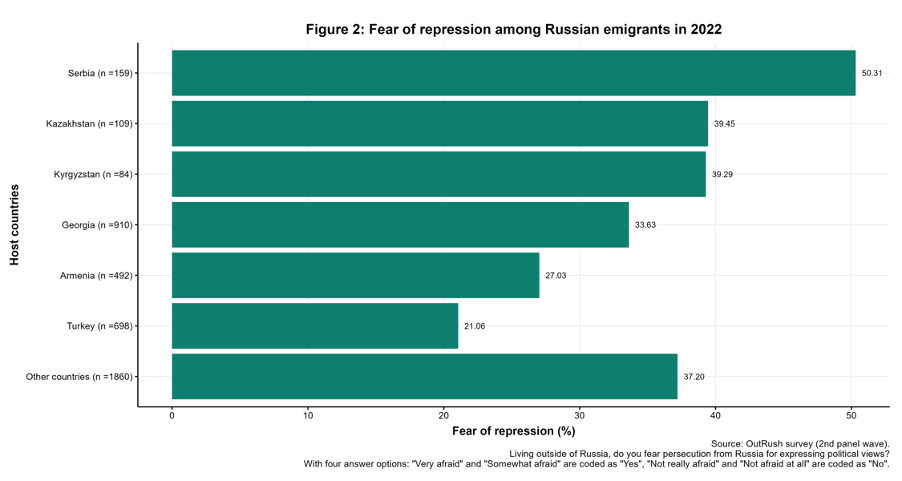

Our respondents also worry about pressure from host countries as exercised through entry and residency requirements. Figure 2 relies on two waves of OutRush survey data to illustrate respondents’ fears of different types of repression carried out by host countries.

Anecdotal evidence of immigration experiences fosters the uncertainty that is captured in Figure 2. A respondent in Georgia was denied a residence permit even though he was already employed by a local company (male, Georgia, July 25, 2023). Media outlets have reported that a journalist and NGO employee were denied entry to Georgia because of their status as “foreign agents,” as was an anti-domestic violence activist. Similarly, a prominent Russian anti-war activist was forced to leave Serbia because of their political activity.

Interestingly, these data do not reflect more recent changes in some host countries. Turkey, which granted more than 150,000 residence permits to Russians in 2022, stopped issuing new ones in January 2023. Many respondents stated that obtaining a residence permit in Turkey is now nearly impossible, which is driving them to leave the country as their permits expire.

The volatility of the Russian ruble is another issue that poses a significant challenge for migrants, some of whom work remotely or rent out their apartments in Russia to support themselves. During the second half of 2022, the ruble remained relatively stable, but by 2023 those with Russian-sourced income were experiencing a drop in their purchasing power due to the depreciation of the Russian currency. One respondent recalled that when he entered Georgia in Fall 2022, the exchange rate was about 18 rubles per lari (Georgian currency), while by the time of the interview, it was 32 rubles per lari (male, Kyrgyzstan, June 11, 2023). Simultaneously, the continued influx of Russians spurred inflation in host countries, forcing less-wealthy members of the diaspora to extend their working hours to balance budgets. Overall, OutRush respondents report significant financial losses since emigration.

While economic challenges are common across diaspora communities, for Russian wartime migrants, tensions within host countries—and between host countries and Russia—make these pressures even more acute. Similarly, the Western sanctions regime and entry restrictions heighten the economic costs of migration and increase barriers to establishing bank accounts and gaining employment, both essential for daily life.

Additional Challenges: Employment, Financial Management, and Isolation

As in many migrant communities, employment is a significant challenge. OutRush surveys show that 22 percent of migrants lost their jobs either upon leaving Russia or between waves of migration. According to one respondent, “Many people don’t have a remote job and there’s nothing to strive for and it’s almost impossible to find a job” (male, Turkey, June 3, 2023). Many others, meanwhile, have retained jobs in Russia or perform other types of remote work. Still others have found jobs that are not commensurate with their skills and level of training.

Western sanctions have influenced migrants’ abilities to transfer funds using credit cards and local banks. For respondents who managed to maintain remote work or found jobs in local companies, it was difficult to open a local bank account and transfer money from Russia. Once major payment platforms like Visa and Mastercard cut off Russian customers from using their services, they were compelled to rely on alternative routes like UniStream and Golden Crown, which charge substantially higher fees. Respondents expressed disappointment with these restrictions: “This is an absurd situation: we left the country; we clearly express our protest against the war, yes; we refuse to pay taxes there; we don’t go to the front as volunteers, yes; we agitate people against the war—but they put spokes in our wheels, and [they started] limiting cards” (male, Georgia, April 11, 2023).

Remote working for Russian firms, as well as financial constraints, contribute to deep fears about personal safety and transnational repression. Many respondents fear Russia’s 2022 censorship laws about “discrediting the Russian military” and “spreading false information.” Others expressed concerns that their host countries would collude with the Russian authorities to extradite them if their anti-war stance were to attract the attention of Russian law enforcement. One of the most common concerns among respondents is that the Russian authorities will punish their relatives: “I’m not afraid for myself, because I don’t plan to go there [to Russia]. I… this is probably paranoia, but I’m afraid for my mother… if there is a potential possibility that my activity could harm my family, my relatives, whom I cannot take away, who cannot go anywhere from there…” (female, Georgia, July 2, 2023).

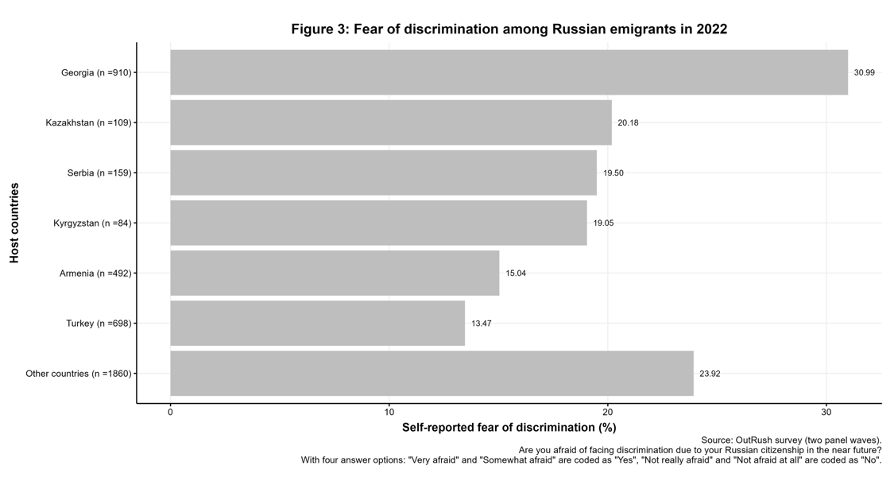

Anonymous denunciations are another source of fear. Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Soviet-style culture of denunciation quickly returned. The fear is that anyone with an anti-war stance could face an anonymous denunciation from anyone with a pro-war position. A month after the start of the full-scale war, OVD-Info published an article describing how neighbors informed on others who hung anti-war symbols in their windows. One young woman indicated: “I’m afraid of denunciations. Really, it is the denunciations that scare me the most” (female, Kazakhstan, July 18, 2023). Such fears are only increasing with time. At the same time, the data in Figure 3 suggest that host communities are mostly regarded as friendly. Few of our respondents recalled more than one or two unpleasant encounters in the countries under study.

The fear of popular discrimination varies across host states. This fear is greatest in Georgia, where just under one-third of respondents express such a concern. In Turkey and Armenia, such fears are significantly lower. In Kazakhstan, Serbia, and Kyrgyzstan, one-fifth of respondents share similar concerns. Outside our countries of study, almost one-quarter of respondents fear popular discrimination.

Finally, our respondents consistently report isolation, disempowerment, and mental health issues. Some have experienced severe depression; many report constant “doom-scrolling” through news feeds. Others report issues with personal and national identity. A female respondent from St. Petersburg now residing in Georgia explains: “I completely lost my Russian identity. And at some point, it was very hard because you don’t understand who you are. But you don’t want to feel Russian” (female, Georgia, June 22, 2023). For some, the continued restrictions on Russians’ transnational movement (especially to Europe) and the lack of international support constrain their plans and aspirations. One respondent describes this frustration: “Is anyone helping? No one is helping. It turns out that Russia does not need us, and the Europeans do not need us either. Although they all talk about the fact that they help refugees, and those who are against the war are good guys… Nothing like that” (female, Serbia, June 9, 2023).

Supporting Russia’s Wartime Migrants

Our interviews point to the most critical areas of need, as defined by migrants themselves. For most of our respondents, the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine has caused enormous mental distress and economic strain. Nevertheless, they have managed to establish horizontal connections and navigate multiple host country environments. While some studies suggest a significant percentage of Russian migrants would like to return home, they will not do so until conditions are safe. The biggest impediments to political and social activism within the diaspora are a lack of housing and material support, concerns about personal and family safety, and non-integration into the international community and market.

If the West seeks to play a role in reshaping postwar Russia, it remains important to engage with the wartime diaspora. We argue that the relatively forward-looking German model of accommodation of wartime migrants provides an important model for combatting migrant instrumentalization, a fear that guides policies in the West and serves a political rather than security purpose. Providing Russian migrants with governmental and NGO support of the type available to other diasporas that have left their home countries due to authoritarian repression would facilitate this. Moreover, supporting migrant communities also supports host countries that face economic, social, and political pressures from domestic constituencies. To that end, we propose international discussion of the following policies that engages all stakeholders: migrants, host countries, international financial and political organizations such as the World Bank, UN and EU, and non-governmental institutions:

- Develop secure screening processes to open Western countries to Russian migration to provide opportunities for migrants and reduce pressure on existing host countries

- Work across public-private boundaries to ease access to banking and credit cards and thus integrate migrants into local and international markets

- Create channels of communication among migrants, NGOs, and Western governments to craft and educate stakeholders about policy responses

- Support job fairs to link migrants with local and remote employers and educational opportunities; provide training and support for job searches and applications

- Provide training to increase migrants’ personal security: computer and communications technology, financial and identity safety, and reporting transnational repression

- Provide community language training in English and host-country languages

- Provide online mental health support

- Assist host countries in mitigating the social welfare costs of diaspora communities

Emil Kamalov, a doctoral researcher at the European University Institute (EUI), is a sociologist and political scientist working on the societal impact of Russian migrants after February 2022, inequalities, discrimination, and political remittances using experimental methods. He has published in Russian Analytical Digest, Economic Sociology, Political Science and Monitoring of Public Opinion.

Veronica Kostenko holds aPh.D. in the sociology of migration and is a former dean of the Sociology Department at the European University at St. Petersburg. She has taught doctoral courses on advanced quantitative methods and applied research on inequalities. She has published on gender studies, particularly in the Arab world, and on migration in Democratization, the Journal of Computational Social Science, and Survey Research Methods.

Andrei Semenov is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Nazarbayev University. He studies political mobilization, civic and urban activism, and subnational politics. He has held post-doctoral fellowships at Yale and the University of Tampere. He has published in European Political Science, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, East European Studies, Post-Soviet Affairs, Problems of Post-Communism, Russian Politics, and Social Movements Studies.

Ivetta Sergeeva is adoctoral researcher at the European University Institute and holds an MS in Social and Political Sciences and an MA in sociology from the European University Institute. She is trained in mixed-methods research, survey design, data management, and analysis. Her interests include discrimination, civil organizations, and the effect of inequality on political behavior.

Regina Smyth is Professor of Political Science at Indiana University. She writes on electoral politics, protest, and activism in Russia and other post-Soviet states. Her recent work includes Elections, Protest and Authoritarian Regime Stability (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and Varieties of Russian Activism (Indiana University Press, 2023).

Mikhail Turchenko is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Indiana University’s Ostrom Workshop. He studies electoral engineering, party system fragmentation, voting in authoritarian elections, transitional justice, and transnational repression. His work has appeared in Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Demokratizatsiya, Europe-Asia Studies, Post-Soviet Affairs, Problems of Post-Communism, and Russian Politics.

Margarita Zavadskaya is aSenior Research Fellow at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA), Finland. She focuses on Russian politics, elections and protests, authoritarian politics, and the role of public opinion under authoritarian conditions. She has published in such journals as Democratization, Post-Soviet Affairs, Europe-Asia Studies, East-European Politics, and Russian Politics.