President Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine is both a strategic conflict with the West to reshape the post-Cold War European order and an identity project for Russia. While the strategic aspect has been well studied, the second roots of the war are more complex because the Kremlin has produced multiple ideological narratives on Russia’s nation building. This nebula of contradicting frames has been used opportunistically, and interpreting which node is genuine enough to inspire causing such calamity in Ukraine has not been obvious. The notion of Russia projecting itself—still or again—as an “empire” has gained momentum because Putin justified the invasion in the name of restoring Russia’s imperial legacy. In his June 9 speech, he praised Peter the Great’s policy of “return and consolidate” and stated that it was his mission to emulate the Russian Emperor.

Yet using the “empire” lens to understand the entirety of Putin’s presidency is mistaken; this has been an evolution, a theme that has gradually gained dominance from a pool of many ideas. The Kremlin reinvented Russia as an imperial power because other forms of great power expression, especially soft power, failed to deliver what the Russian authorities were hoping for: the right to shape the post-Cold War order in Europe and in Eurasia. Moreover, references to historical models serve different purposes. They inform us about the aspirational nature of the political regime, its international recognition, its territorial projections, and its cultural nostalgia. Based on these two assumptions, this memo first looks at the evolution of the “empire” theme in Russian presidents’ speeches, and then explores different readings of the imperial reference: historical continuity, decommunization, autocracy, and territorial expansion. It does not discuss whether Russia is indeed an empire or whether it retains colonial features but how the Russian political language reinvented Russia as an empire.

Reinventing Russia as an Empire

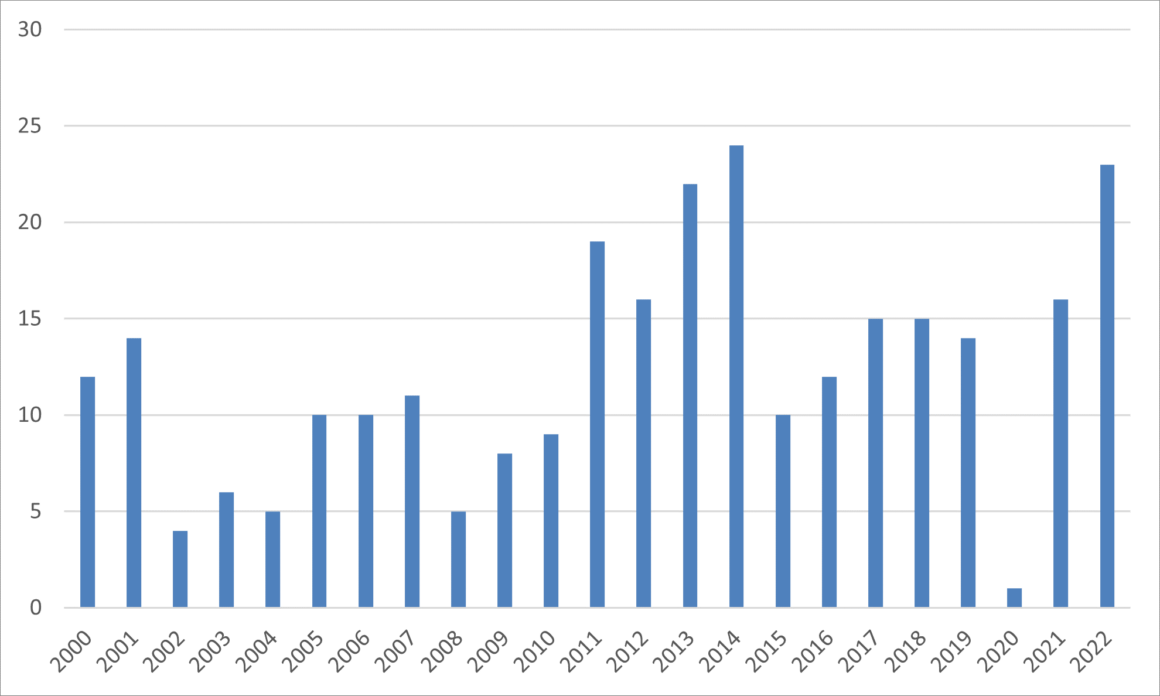

A search of presidential speeches from 2000 to 2022 (see Figure 1) shows that the theme of ”empire” became more prominent after 2011, with peaks during the crisis years of 2011-2014 and 2021-2022. As expected, during his presidency, Dmitry Medvedev referred less to “empire” than Putin, although he did participate in relaunching the theme from about 2011.

Figure 1. Mentions of “Empire” in Presidential Speeches, 2000-June 2022

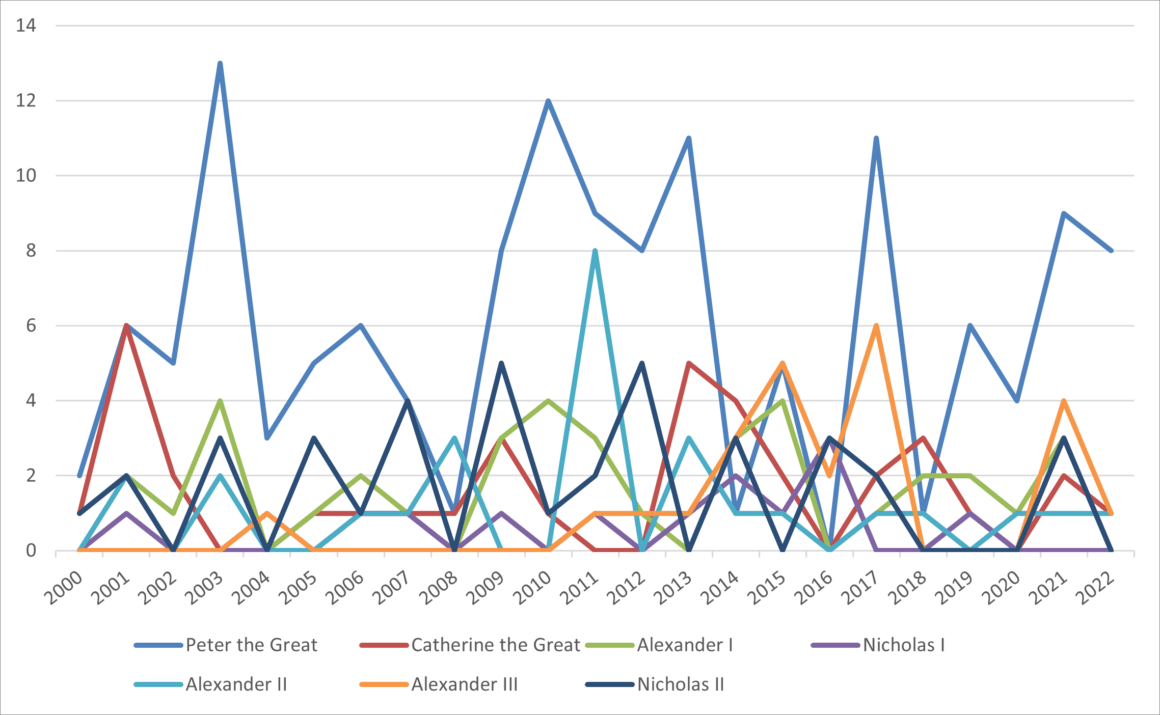

Looking at which tsars Medvedev and Putin have referenced (see Figure 2), one can notice the unchallenged preeminence of Peter the Great ahead of all others with 64 mentions. Here too, the turning point is 2011 (under Medvedev’s presidency), with 22 mentions of Peter before and 42 afterward. But it is the meaning of the references to Peter the Great that has evolved the most. They peaked during Putin’s first term to celebrate the modernizer who opened the famous “window on Europe.” Putin’s 2003 citation is emblematic of that vision: “Peter I dreamt of a country strong, dynamic, and open to the world. And he didn’t only dream. He did open Russia to the world, and the world to Russia.”

Peter then disappeared in the first three years of Medvedev’s presidency until 2011, when the Russian president mentioned him as the “creator of a strong and open power (derzhava).” After that, Putin’s references to his reformist role discard the “window on Europe” and emphasize Peter’s status as a derzhavnik—one who believes in greatness. Putin associates his name with ideas of defense, a robust northern fleet, military schools and procedures, laws and procurators, and most recently, references to the Emperor’s reconquest of lost territories and “return and consolidate” policy. We can also presume that Peter the Great’s 43-year-reign is, too, pleasing to Putin, who seems to see himself in power until his death.

The other tsars receive episodic mentions, and all have their minuses for Putin’s self-vision. Alexander II was too liberal, and it cost him his life. Nicholas II was weak, did not resist the forces of revolution, and abdicated. Even the most autocratic leaders had shortcomings: Nicholas I lost the Crimea War, and Alexander III was more isolationist than expansionist.

Figure 2. References to the Main Russian Tsars in Presidential Speeches, 2000-June 2022

The Empire as Russia’s Longue Durée

References to Russia’s imperial past have been used in Putin’s language as part of the narrative of Russia’s “one-thousand-year statehood” (tysiacheletniaia gosudarstvennost’). What matters here is the historical continuity of the state beyond the many changes to the country’s borders over time and the country’s two major political disjunctures in 1917 and in 1991. This insistence on state continuity is nothing specifically Russian: France’s roman national is built on the continuity between the French monarchy and its enemy, the French Revolution, taught to young pupils as one and the same state entity whatever its political identity.

With Putin’s conservative turn in 2012, the Kremlin’s official language shifted heavily toward more history and culture to the point of becoming one of the central components of Putin’s discourses, increasingly more detached from everyday realities. Many close observers of the presidential administration have been mentioning that with age and isolation, Putin has been gradually diving into Russia’s history in search of his own historical legacy.

The president has become increasingly involved in culture, religion, and history, reflecting the securitization of Russia’s nation building. In 2014, for instance, the Presidential Administration used the term “history” more than it had in the past two decades, to the point that Russian history outpaced themes related purely to Russian cultures, such as literature (literatura or slovesnost’), classical music, cinema, composers, thinkers, folklore, and tradition. This historicization of Putin’s speeches has thus contributed to the growth of references to Russia as an “empire.”

The Empire as Decommunization

Largely unnoticed by Western punditry is the use of the Russian empire as a decommunization tool—a paradoxical component of Putin’s speeches that counterbalances his emphasis on the Soviet Union.

References to the Romanov empire were (already) common in the early 1990s, at a time when the Yeltsin team was using them to criticize the Soviet regime and its supporters and reconnect with a past that sounded ostensibly more European. With Putin’s officialization of a more positive view of the Soviet past—in fact already noticeable in Yeltsin’s second mandate—one could have imagined that the imperial past would be put aside. But that was a misunderstanding of how the Russian president understood the Soviet experience.

Over the years, Putin became more and more vocal in his critique of the Bolsheviks and especially of Lenin. The Russian president stated on several occasions that the Bolsheviks betrayed the nation by signing the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the German enemy and losing large portions of Russian territory. In 2014, upon visiting the Seliger camp, which brings together patriotic youth movements, he declared that the “Bolsheviks wished to see their Fatherland defeated,” adding that “this was a complete betrayal of national interests.” In 2016, once again asked about his opinion of Lenin, Putin accused the revolutionary of “having planted a bomb under the building named Russia, and it collapsed.”

The peak of Putin’s anticommunist language reached its apogee in his February 21, 2022 speech. There he argued that the Bolsheviks created the Ukrainian state at the expense of the Russian heartland. Not only did the Ukrainians have the Bolsheviks—and then Stalin and Khrushchev—to thank for having established their artificial statehood, Putin stated, but they also have post-Soviet Russia itself to thank for not claiming the territories that became Ukraine under the Soviet decision. “And today, the ‘grateful progeny’ has overturned monuments to Lenin in Ukraine. They call it decommunization … We are ready to show what real decommunizations would mean for Ukraine,” concluded Putin.

In that version, the “empire” is posited as the opposite of the Soviet Union. While the Soviet Union promoted nationalities and their republics to the detriment of the empire, the empire gave priority to Russia and forced the peripheries to merge with the center. Yet this does not mean references to the Soviet Union have disappeared. Even if Putin has publicly disliked the Bolsheviks, in the newly occupied Ukrainian territories, Russian victory is celebrated by new Lenin statues as a symbol of the “return” of/to the Soviet Union.

The Empire as a Regime

Another reading of the empire is related to nostalgia for its political regime. The Kremlin has let a monarchist lobby emerge on the public scene. It involves prominent figures such as Nikita Mikhalkov in the cultural field, Konstantin Malofeev in the ideological realm, and Vladimir Yakunin, the former director of Russian Railways who has been close to the president for a long time. Several hawks like referring to the tsarist regime. Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin for instance recently evoked the need to be inspired by the tsarist educational system to reform Russian schools. Putin himself is said to have been influenced by White General Anton Denikin’s memoirs, which contain a distinct hostility to the idea of an independent Ukraine. Putin has also supported the repatriation of Denikin’s remains, as well as those of the reactionary philosopher Ivan Ilyin.

Yet on several occasions, Putin has mocked those who seek a return to monarchism. Half-joking, he has commented on his reluctance to live in pre-revolutionary Russia, where his ancestors worked as serfs—openly criticizing all those romanticizing tsarism. In 2017, his press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, reacted to the declaration of the head of the Crimean Republic, Sergey Aksenov, about the need to restore monarchism. Peskov explained: “Putin regards this idea without any optimism. He has been asked the same question several times these last years … and very coldly relates to these discussions.” A few days later, Putin himself declared, “thank God we do not have a monarchy, but a republic.”

The state policy toward the Romanovs has been quite consistent. It celebrates the dynasty as part of Russia’s history and statehood and as a time of prestige and expansion for the empire and plays down any setbacks such as the Crimea War and the Russo-Japanese war. As part of that position, the authorities supported the reburial of Nicholas II and his family and the legal restoration of their status. The authorities have also accepted the registration of the Imperial House’s Chancellery as a non-profit organization that works as the informal embassy of the imperial family. But past that symbolic stage, the authorities were not keen to give the Romanov heirs any specific status and were even less eager to restore tsarism. They use its symbolic values only to claim the right to an authoritarian regime that would refuse West-inspired liberalism as well as return to a failed Communism.

The Empire as Territorial Greatness

The last but maybe more important reading of the empire communicates its spatial materiality. At the grand reopening of the Russian Geographical Society in 2009, then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin explicitly linked the greatness of Russia as a state and as a culture to the size of its territory: “When we say great, a great country, a great state—certainly, size (or expanse, masshtab) matters … When there is no size, there is no influence, no meaning.” This assumed link between size and relevance exemplifies the idea, common in Russia, that the destiny of the country is linked to its geographic scope. The patriotic historical exhibition “Russia, my history” has epitomized that vision in a simple coloring scheme: in red is the period of history when Russia’s territory retracted, and in green, those when Russia’s territory expanded.

Yet, one may refer to Russia’s size uniquely with a view of its current territory, which still represents one-eighth of the globe: celebrating Russia’s quite unique spatial features does not automatically imply it needs to expand outside of its official borders. Putin did say that “Russia’s borders do not finish anywhere” (granitsy Rossii ne konchaiutsia nigde) in 2016, but it was a joke at a children’s contest at the Russian Geographical Society. Yet Russia’s narrative has always maintained ambiguities: the notions of “Russian World,” “Eurasia,” and “compatriots” have unprecise undertones. They can be read as a form of Carl Schmitt’s Grossraum (classic territorial expansion) or “auratic bodies” that are religious, cultural, and social bonds that are broader geographically than citizenship but legally less binding.

For years Moscow played more the “auratic bodies” than the Grossraum card—with, of course, the major exception of Crimea’s annexation—until its invasion of Ukraine. After that, it advanced the reading of Russia’s contemporary borders as unfair or illegitimate and therefore open to contestation. The “empire” as a reference to legitimize territorial expansion has now been made explicit. Yet even today, in occupied Kherson-Zaporizhzhia as well as in the newly conquered parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, one may notice the tensions, inside the Presidential Administration, between a strategy of pure annexation and integration into the Russian Federation and a strategy of occupying territories with the aim of bargaining them later.

Conclusion

Reading Putin’s Russia projecting itself as an empire by design is analytically mistaken: the empire has been a progressive reinvention of the country’s political and territorial identity, implemented because the other projections of Russia’s great-power status have failed.

Consequently, interpreting the quest for territorial expansion in Ukraine as pure imperialism for the sake of just getting bigger is also misguided: not every territory is worth reconquering. The Kremlin is not interested in reintegrating Central Asia, for instance, and probably even not most of the South Caucasus. Instead, the quest is a blend of responding to strategic and normative challenges posed by the West and recreating a mythified Russia in which historical junctures and territorial discontinuities would be erased or repaired. Ukraine finds itself the central piece of both components of the blend: it embodies the failure of Russia to be attractive enough to keep Kyiv in its orbit against Western competition and symbolizes the historical and territorial disjunctures that have broken the mythified east-Slavic unity.

In that blend, the reference to the “empire” combines elements of territorial greatness (Russia has been cut off from territories that are meaningful historically and culturally), elements of historical continuity (Russia should reconnect with its one-thousand-year statehood to be strong and protected from external influences), and elements of regime ideology (tsarism as the embodiment of autocracy and “traditional values”). Yet, it does not either entirely embrace each of these components: there is no quest for reconquering the whole of the Soviet Union or of the Russian empire; there is no will to restore the imperial stature of a Romanov Russia as part of the European concert of nations but on the contrary to move toward isolationism, and there is no rehabilitation of tsarism per se.

Even if the state-sponsored ideological language has become more rigid, it remains an ideological patchwork, as shown by the concert “Khit Parad SSSR” to be held at the Christ the Savior Cathedral (and then apparently canceled). Yet Russia as an “empire” is probably the most coherent patchwork formulated so far because it is broad enough to encompass many different readings. It conflates state projection abroad, nation-building language, regime securitization, and Putin’s self-vision as a ruler whose historical role in bringing back power and dignity, as well as lost territories, will not be questioned by the future leadership.

Marlene Laruelle is Research Professor and Director of the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (IERES) at the Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University.