Russia’s war in Ukraine is reshaping how Uzbeks view Moscow. Tashkent’s political elites have repeatedly reminded Moscow of the value that Uzbekistan places on state sovereignty and have resoundingly repudiated actors questioning Uzbek state sovereignty. At the same time, these political elites have taken care to avoid alienating Moscow, especially at a time when Uzbekistan stands to benefit from Moscow’s pivot toward Central Asia as the West turns away from Russia.

Survey and focus group data reflect similarly mixed sentiments within Uzbek society at large. Russia’s reputation has eroded since the start of the war. Perhaps most problematic for Moscow is the fact that Uzbeks under the age of 30 have far less favorable views toward Russia than older generations. That said, a slim majority of these younger Uzbeks (and far wider majorities of older Uzbeks) still view Russia in a favorable light. The same cannot be said for the United States and China, which many Uzbeks—especially older Uzbeks—view with suspicion.

This memo explores these mixed views among Uzbek state and society toward Russia, the United States, and China. Section one summarizes relevant statements made by Uzbek elite since the start of the war in Ukraine. Section two covers Uzbek public opinion, presenting findings from a nationally representative survey that my colleagues and I conducted in the fall of 2022, seven months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February. The final section presents the findings of focus groups that my colleagues and I conducted in Tashkent and Samarkand in the summer of 2023. Taken together, this memo suggests that Uzbeks, while still keeping Beijing and Washington at arm’s length, are beginning to question their country’s relationship with Moscow. How far Uzbek state and society will take this questioning will ultimately depend on economic factors—on whether Uzbekistan’s now-strained trade relations with Russia can withstand the further erosion that will likely accompany a prolonged war in Ukraine.

The Response of Uzbek Political Elites to Russia’s War in Ukraine

The Uzbek government, like those of other Central Asian states, is prioritizing its national interests while navigating how to best respond to Russia’s war in Ukraine. These interests are multifaceted and rarely easy to pursue. The Mirziyoyev government wants to make it clear to Russia that Uzbekistan’s sovereignty is non-negotiable. At the same time, regional economic, political, and security imperatives compel President Mirziyoyev to tread carefully in his country’s bilateral relations with the Putin regime.

Uzbekistan, wary of Russia’s actions in Ukraine, is actively diversifying its international partnerships. Newly engaged—or, as is the case with the United States, newly re-engaged—Western partners demand that Uzbekistan not provide material support to Russia’s war of aggression. Importantly, however, determining how best to respond domestically to Putin’s war is an equally challenging prospect. A notable segment of Uzbek society is displeased with Moscow. At the same time, Russia remains a critical trade partner, source of labor remittances, supplier of natural gas, and, in contrast to other foreign countries, a government that both Uzbek state and society understand and are comfortable with.

Given this wide array of sometimes opposing foreign relations imperatives, it may come as a surprise that the Mirziyoyev government, in its response to the war in Ukraine, has avoided alienating any key international actors while making reputational and material gains with other bilateral and multilateral partners. Nowhere is this adept balance more apparent than Tashkent’s most important and sometimes challenging international partnership: its bilateral relationship with Moscow.

Uzbekistan, in contrast to Kazakhstan, which shares a 7,600-kilometer border with Russia, is not a centerpiece of Russian irredentist imaginations. Whereas President Putin and former President Medvedev have both asserted that Kazakhstan is not a real state and suggested that Russia has valid claims to Kazakh territory, only B-list Russian nationalists have advanced similar claims with regard to Uzbekistan. The xenophobe Zakhar Prilepin is an exception that proves the rule here. Known both for his ultra-nationalist writings and for fighting alongside pro-Russia Donetsk separatists, Prilepin made the following declaration in December 2023: “since 2 million of your citizens are on our territory, we claim your territory… Who forbids us to do anything in Eurasia after the parade in Kyiv? No one.”

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs quickly distanced Moscow from Prilepin’s comments. In the months since, Moscow has gone to considerable lengths to shore up relations with Tashkent. In April 2024, Moscow’s trade representative in Tashkent, Igor Kamynin, pledged that Russia would maintain parity with China when it comes to trade turnover with Uzbekistan—and this lofty pledge has been backed by real action. In 2023, Russia’s Gazprom and Uzbekistan’s UzGasTrade agreed to increase shipments of Russian national gas supplies to Uzbekistan from three billion cubic meters to 11 billion cubic meters by 2026. In April 2024, Russia’s Lukoil and the Uzbek Ministry of Poverty Alleviation agreed to a program aimed at facilitating Uzbek employment with the Russian energy giant.

Uzbek President Mirziyoyev has been careful to avoid antagonizing his Russian counterpart. The Uzbek president was in attendance at Red Square for Putin’s Victory Parade on May 9, 2023. Mirziyoyev has also instructed his country’s ambassador to the United Nations to refrain from voting on or voting against UN General Assembly resolutions censuring Russia for its war in Ukraine. At the same time, the Mirziyoyev government, like all Central Asian governments, must engage a domestic audience that has growing misgivings about Russia, its colonial legacy, and its general disregard for international norms of state sovereignty.

At times it appears as though Uzbekistan’s leaders share these misgivings. President Mirziyoyev, issuing a statement through his spokesman not long after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, stressed that Uzbekistan maintains “close, friendly relations with both Russia and Ukraine” and is “interested in ensuring peace, stability, and sustainable development in our vast region.” Uzbek Foreign Minister Abdulaziz Komilov was more direct the following month, emphasizing that Uzbekistan “recognizes Ukraine’s independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity. We do not recognize the Luhansk and Donetsk republics.”

Survey Findings on the General Public’s Perceptions of Uzbek Foreign Relations

Komilov’s defense of Ukraine’s sovereignty was prescient. The Uzbek foreign minister’s statement not only put ultra-nationalists like Prilepin on warning but also foreshadowed a weakening of Uzbek society’s affinity for Russia. Gallup’s World Poll, conducted annually in Uzbekistan, provides a window into these changing domestic attitudes. In August 2021, 69 percent of the 1,000 Uzbeks that Gallup polled indicated that they “approved of the job performance of the leadership of Russia.” By July 2022, that same figure had dipped to 63 percent, and Gallup’s most recent survey in July 2023 found that it had declined even further to 59 percent.

While this 10 percent drop in Putin’s approval since the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine is notable, it is important that we contextualize Uzbek perceptions of world leaders more broadly. Over this same period, Uzbek approval of U.S. leadership dropped from 33 percent to 30 percent, while that of Chinese leadership rose from 33 percent to 39 percent. In short, while the Gallup surveys indicate that the Putin regime has suffered a reputational decline among the Uzbek public in the two years since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Russian government nevertheless enjoys far greater goodwill among Uzbeks surveyed than either Beijing or Washington.

Surveys and focus groups that colleagues and I conducted in the months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provide insight into why—despite Uzbek concerns that Moscow’s imperial ambitions may extend beyond Ukraine as well as widespread displeasure with Russian nationalists like Prilepin—the majority of Uzbeks continue to view Russia in a positive light. Part of the explanation lies in Uzbekistan’s extensive economic, cultural, and linguistic ties to Russia. Beyond the fact that millions of Uzbeks work in Russia, sending economically critical remittances back home, Uzbeks are active on Russian social media platforms, closely follow Russian news sources, watch Russian television and movies, and attend Russian universities.

Importantly, however, these extensive ties with Russia are not the only reason why Uzbeks viewed the Putin regime in a relatively favorable light. Our surveys and focus groups reveal that Uzbeks have yet to fully embrace China and that, as they have for much of the post-Soviet period, they continue to harbor a deep distrust of the United States. In our nationally representative September–October 2022 survey of 1,000 Uzbek respondents, we presented the following hypothetical scenario:

In the future, if hard times come to Uzbekistan—for example, a food shortage, widespread unemployment, hyperinflation, or a pandemic—which country will come to Uzbekistan’s aid?

Despite the ongoing war in Ukraine, 46 percent of respondents indicated that they thought Russia would come to Uzbekistan’s aid. Far fewer—only 20 percent of respondents—anticipated China extending support. Even fewer still—7 percent of respondents—felt that the United States would help Uzbekistan if it were in crisis.

One potential reason for Russia faring well in this hypothetical is Moscow’s historical, geographic, and economic proximity to Tashkent. Uzbek respondents may view Russia as more likely to intervene and support Uzbekistan during a period of crisis for the same reasons that Moscow intervened to help quell the January 2022 protests in Kazakhstan: such interventions in Central Asia are in Moscow’s geopolitical interest, whereas interventions are less likely to fall under the geopolitical interests of Beijing and Washington.

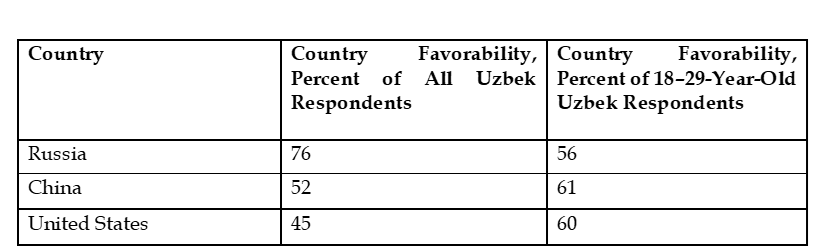

Revealingly, however, respondents’ answers regarding which countries they view in a positive light suggest that, geopolitics aside, Uzbeks are far more positively inclined toward Moscow than either Beijing or Washington. A notable 76 percent of Uzbeks surveyed reported holding a positive view of Russia, while just 52 percent and 45 percent said the same for China and the United States respectively.

This comparatively warm sentiment toward Moscow similarly emerges in respondents’ answers to the following question: “In your opinion, which country at the current moment is Uzbekistan’s main friend?” More than half of those surveyed—54 percent—said Russia. Curiously, despite 52 percent of Uzbeks reporting a positive view of Beijing, only 5 percent of respondents identified China as Uzbekistan’s main friend. Washington fared even worse, with only 1 percent of respondents identifying the United States as Uzbekistan’s main friend.

In an effort to move away from what could be viewed as abstract questions focused on government actors and move toward an issue that affects Uzbeks’ everyday lives, we asked respondents if they would welcome students from various countries as neighbors. More than two-thirds of respondents—68 percent—said they would not welcome students from China as neighbors. Survey respondents were similarly disinclined to having US students as neighbors, with 63 percent reporting that they would prefer not living next to Americans. Russian students were viewed as the least objectionable, with only 44 percent of respondents indicating that they would prefer not to have Russian students as neighbors.

Uzbek society, of course, is far from uniform. Older generations have greater familiarity with Russia than do younger Uzbeks, who have no lived experience of the Soviet Union and who, as a cohort, have spent less time in migrant labor jobs in Russia. Importantly, our survey suggests that attitudes toward Russia, the United States, and China all vary by age group.

These swings in public opinion—a 20 percent dip in Russian favorability and a 9 percent and 15 percent uptick in Chinese and U.S. favorability, respectively—among younger Uzbeks are remarkable and suggest that Moscow should not assume that Uzbek society will continue to be forgiving of Russian neocolonialism in the post-Soviet space. Indeed, as our focus groups reveal, Uzbeks are frustrated with the adverse effects the war in Ukraine is having on the Uzbek economy.

Focus Group Findings on the General Public’s Perceptions of Uzbek Foreign Relations

In an effort to better understand Uzbeks’ views on their country’s key foreign partners in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we conducted focus groups in Tashkent and Samarkand in July 2023. As with our fall 2022 survey, we avoided direct questions about the war in Ukraine in deference to the political environment in which we were conducting our research. Focus group participants nevertheless routinely volunteered their thoughts on the conflict in Ukraine and, more broadly, on Uzbekistan’s relations with Russia, China, and the United States.

A central theme that emerged in our focus group conversations is the familiarity with which Uzbeks view Russia and the concern that Uzbeks have over how the war in Ukraine may adversely affect the Uzbek economy. Emblematic of this sentiment is the observation of a 26-year-old Uzbek woman in Tashkent:

Since Uzbekistan and Russia were in a union for many years, developments in Russia are of interest to us. Many of us work in Russia, and we are interested in how the war might affect us.

Another Tashkent respondent, an Uzbek male between the ages of 18 and 35 (exact age not given), believed that Russia was “on the side of peace.” The respondent was most concerned about how the war would affect trade with Russia. One male 36-year-old Uzbek participant in Samarkand shared similar economic worries:

The war between Russia and Ukraine affects not only these two countries but us as well. The war is leading to inflation, leading to rising food prices.

Focus group respondents, in short, were closely watching the war. While they worried that the war was adversely affecting Uzbekistan’s economy, focus group respondents did not blame Russia for the war or for the economic challenges that Uzbekistan was enduring.

Focus group respondents were less forgiving toward the United States and President Biden. One Tashkent respondent—an ethnically Russian woman between the ages of 18 and 35—likened the U.S. president to a “lizard” and recounted news that she had heard about how President Biden “fell down the stairs.” A male 48-year-old ethnic Uzbek, also from Tashkent, similarly recounted the story about Biden’s fall down the stairs and added that the U.S. president was “giving money to Ukraine”—that it was thanks to Biden that Uzbekistan “has increasing poverty and inflation.”

While care should be taken when extrapolating from focus groups to the population at large, it is worth noting that Uzbek focus group respondents’ assessment that the US is more at fault for the war in Ukraine than is Russia parallels a pattern we identified in surveys where we were able to pose direct questions about the conflict. In our nationally representative fall 2022 surveys in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, for example, 76 percent of Kyrgyz respondents and 59 percent of Kazakh respondents agreed with the statement that “the US provoked the conflict in Ukraine,” while only 41 percent of Kyrgyz and 39 percent of Kazakh respondents agreed that “Russia provoked the conflict in Ukraine.”

China, curiously, was largely absent from the focus group discussions on Ukraine. While participants occasionally mentioned Chinese products and investments, Beijing did not figure prominently into focus group discussions about Uzbek foreign relations.

Conclusion

The picture that emerges from this memo’s analysis of focus groups, surveys, and Uzbek political elites’ statements is a complex one. Russia continues to be viewed in a generally positive light despite its ongoing war in Ukraine. A majority of survey respondents—albeit a slim majority at 54 percent in our fall 2022 survey—identify Russia as Uzbekistan’s “main friend” when it comes to foreign relations, resoundingly topping the 5 percent and 1 percent who identified China and the United States, respectively, as such.

Critically, however, Moscow’s reception among Uzbek state and society has suffered in recent years. Tashkent political elites have warned Moscow both directly and indirectly not to question Uzbek state sovereignty. One finding that emerged from our polling that should be most troubling for Moscow is that Uzbeks under the age of 30 hold more favorable views of China and the United States than they do of Russia. Moreover, our focus groups suggest that the affinity that does exist for Russia stems largely from Uzbeks’ recognition of the deep economic ties linking the two countries. Still, these same focus groups reveal deep concerns over these ties being strained by Russia’s war in Ukraine. Whether or not these ties continue to hold despite this increased strain will shape how Uzbeks—especially young Uzbeks—view Russia in the coming years.

Eric McGlinchey is Associate Professor in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University