In debates about the responsibility for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, television undoubtedly plays an important role in the public’s supporting, ignoring, or opposing the Kremlin’s war. A key aspect of this debate concerns the information environment in Russia and the kinds of news that Russians receive through the media. It is well known that most Russians get most of their news from television—a fact that likely will increase with the ongoing crackdown on foreign news and social media. Now that it seems clear that the military campaign was planned well in advance, it is worth considering how state-controlled media prepared the Russian public in the buildup to war.

Reported here are findings from a study of the frequency and content of messaging on various themes on Russian television. The goal of this approach is not necessarily to re-create Russians’ viewing habits, though one might reasonably assume that more frequently mentioned topics are more likely to have been viewed or noticed. Rather, the frequency and distribution of topics over time reveal the extent to which state-controlled television presented a coordinated campaign. In the absence of reliable public opinion data in war-time Russia, such an approach further suggests insights about the ways that Russians were prepared for and reacted to the onset of war. Despite Russia’s insistence that its invasion was motivated by longstanding concerns—genocide and fascism in Ukraine—the findings show that Russian television only paid brief attention to those concerns and quickly re-focused on other themes. Rather, the priming of the public for war began over a month prior to the invasion with the spread of “war talk” on television broadcasts.

What Was Included in the Study

The data for this study are drawn from the Integrum Profi television broadcast transcripts, which were analyzed on a week-to-week basis from December 13, 2021, through March 13, 2022. The week of December 13 was chosen as a starting point just before President Vladimir Putin initiated a crisis in relations with Russia with the issuance of his ultimatums to the United States and NATO, hence a coordinated media campaign in Russia might also be observed from this time. Five channels were chosen for analysis: the state-run channels Pervyi Kanal (1tv) and Rossiia 1, the pro-government NTV (owned by Gazprom Media), Moscow’s public television station TV Tsentr, and the independent Dozhd TV. Dozhd TV was included as a check on whether a topic has broad resonance across the political spectrum, though it bears noting that it was taken off the air after the start of the war and ceased operation on March 3, 2022.[1]

The Kremlin’s Humanitarian Claims and Narrative Drift

Beginning with Russia’s claim that its invasion was intended to stop an alleged genocide in eastern Ukraine, it is worth recalling that a similar claim was made (and quickly dropped) at the start of Russia’s 2008 war with Georgia. Russia similarly invoked preventing genocide and opposing fascism as justifications for occupying Crimea and supporting separatist republics in eastern Ukraine in 2014. If the government’s concern was principled, then one would expect to find at least somewhat constant signaling of this concern from the start of the crisis in December 2021 through the invasion of Ukraine and the early stages of the war. One would also expect genuinely humanitarian concerns to be reflected in reporting across the political spectrum.

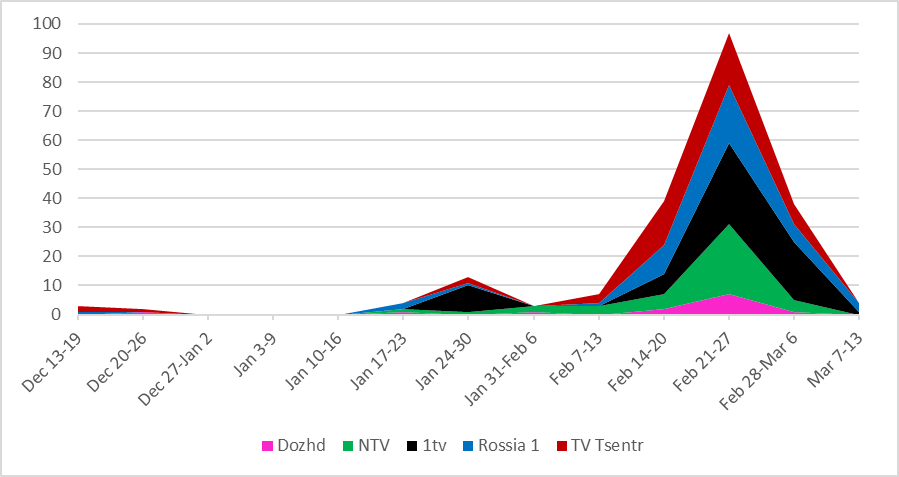

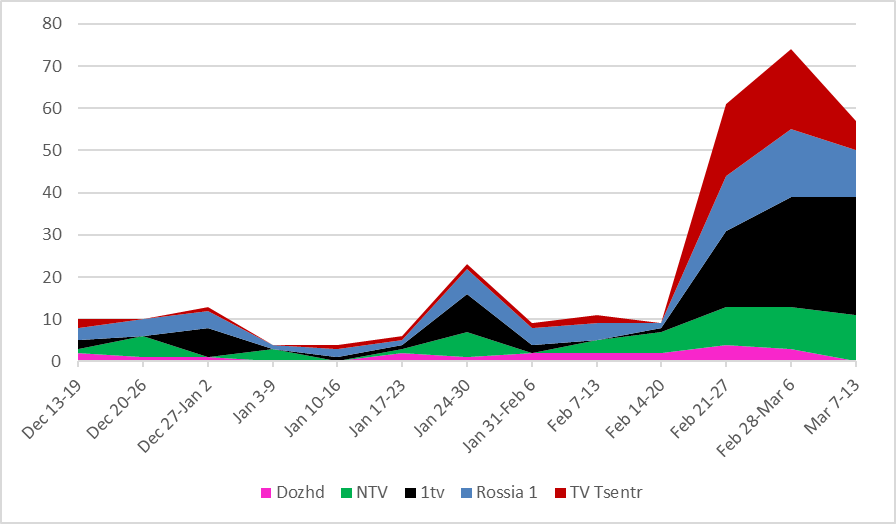

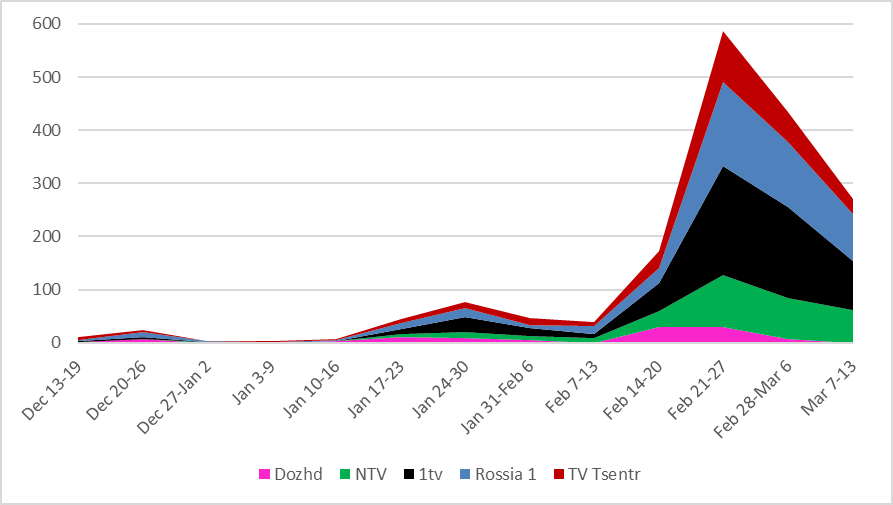

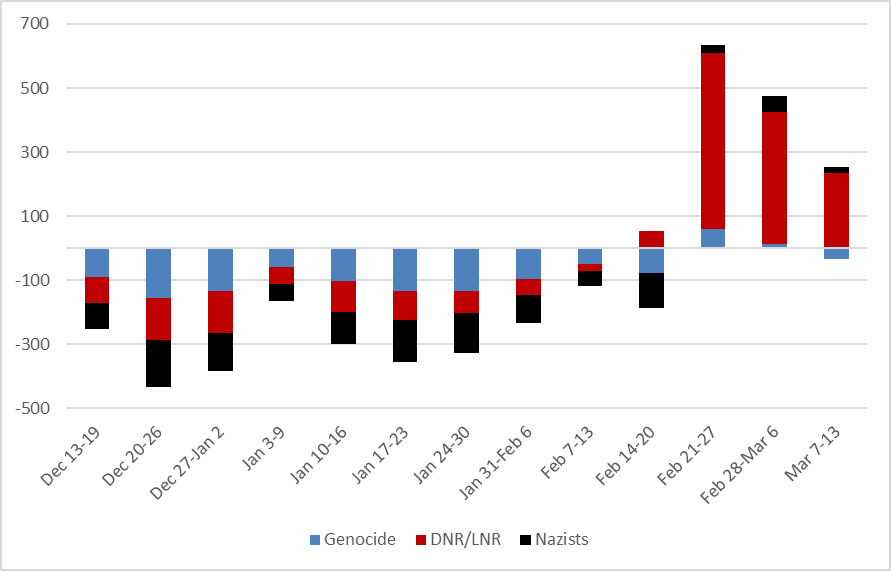

Turning to the analysis of broadcast transcripts, quite a different picture emerges. Genocide barely rated mentioning save for a small spike by the state channel 1tv in late January (see Figure 1). By the time the decision to go to war had been taken, however, mentions of genocide skyrocketed on state-owned and pro-government television channels. Strikingly similar patterns are evident for mentions of “Nazist”[2] (Figure 2) and the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, commonly referred to as “DNR” and “LNR”[3] (Figure 3): both were hardly mentioned until it was time to prepare the Russian public for the decision to go to war in early- to mid-February. This instrumental mobilization of genocide and anti-fascism fits past patterns in Russia’s justifications for attacking its neighbors.

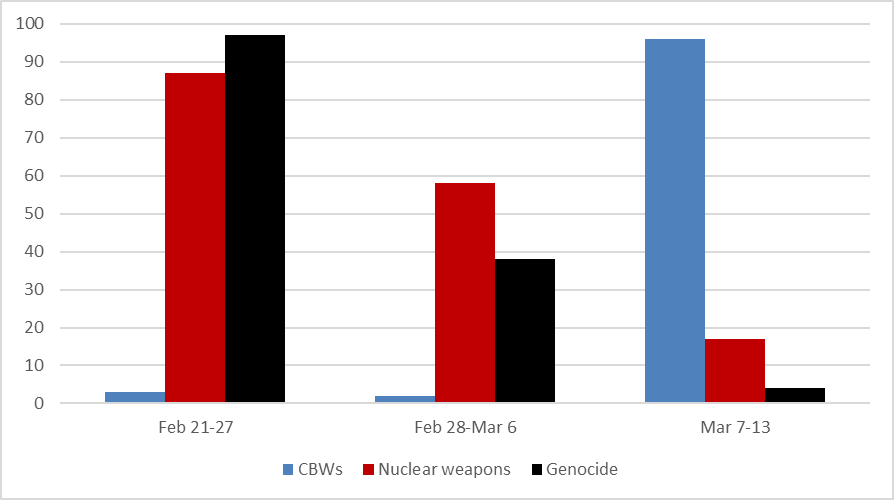

Further evidence of the instrumental mobilization of humanitarian concerns is found in the shifting narratives in the weeks immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Figure 4). In the two weeks following the start of the war, “genocide” almost completely disappeared from mentions on Russian TV. A new narrative emerged concerning fears that Ukrainian nationalists might get ahold of nuclear materials to make dirty bombs, but this quickly dissipated after Russian forces’ messy and alarming seizure of the Zaporizʹka nuclear power plant. Instead, that narrative was quickly replaced by new claims about the purported threat that increasingly desperate Ukrainian forces might resort to using (or had already planned to use) chemical and biological weapons.

Russia’s humanitarian justifications were not consistently signaled via state-controlled Russian television either before or after the invasion. Rather, the three themes of genocide, Nazis, and separatist republics were scarcely mentioned until a brief coordinated surge in late January and then a massive spike in coverage starting in mid-February. Even with war raging in Ukraine, they started to decline in broadcast mentions after the invasion. In fact, mentions of genocide virtually disappeared from Russian airwaves within two weeks of the invasion. From this, it is difficult to view Russia’s humanitarian justifications for invading Ukraine as little more than cynical manipulations that served to put such terms and discourse into circulation, perhaps providing viewers with a regime-friendly lexicon to frame and discuss the war.

Broadcasting Russia’s Security Concerns

The relative absence of genocide and anti-fascism in public discourse in Russian media until the eve of war perhaps explains why Putin’s ultimatums in December 2021 focused less on Ukraine than on the United States, NATO, and Russia’s security concerns. Of course, “security” can be understood in many ways. Since the late-1990s, security discourse in Russia has tended to involve post-Cold War grievances concerning its international standing and demands for recognition of its status as a great power. Particularly since 2014, these security concerns further involve disagreements (sometimes quite emotional) over whether Russia gained or lost international status.

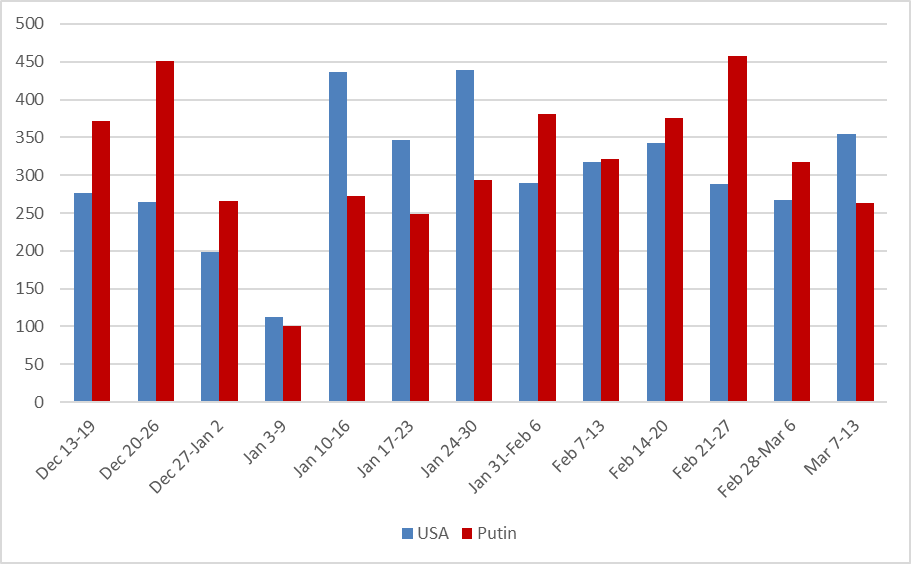

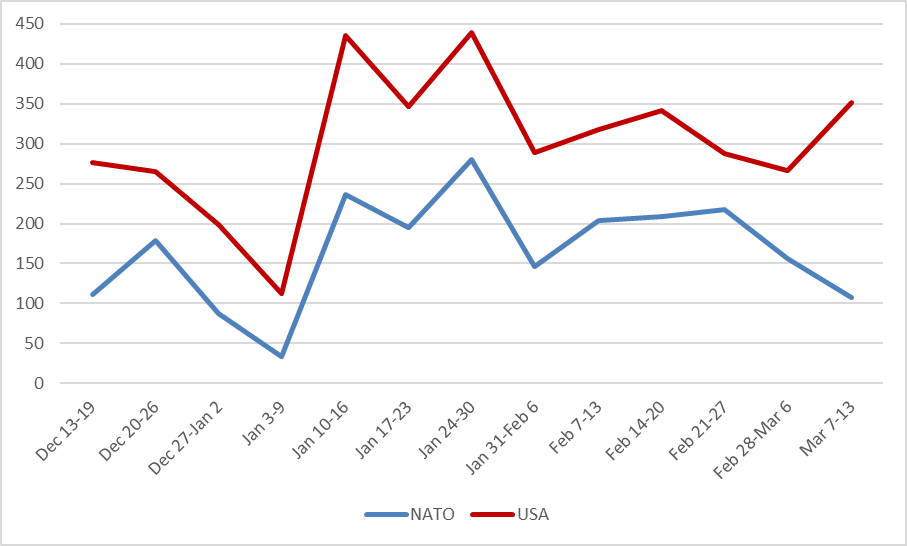

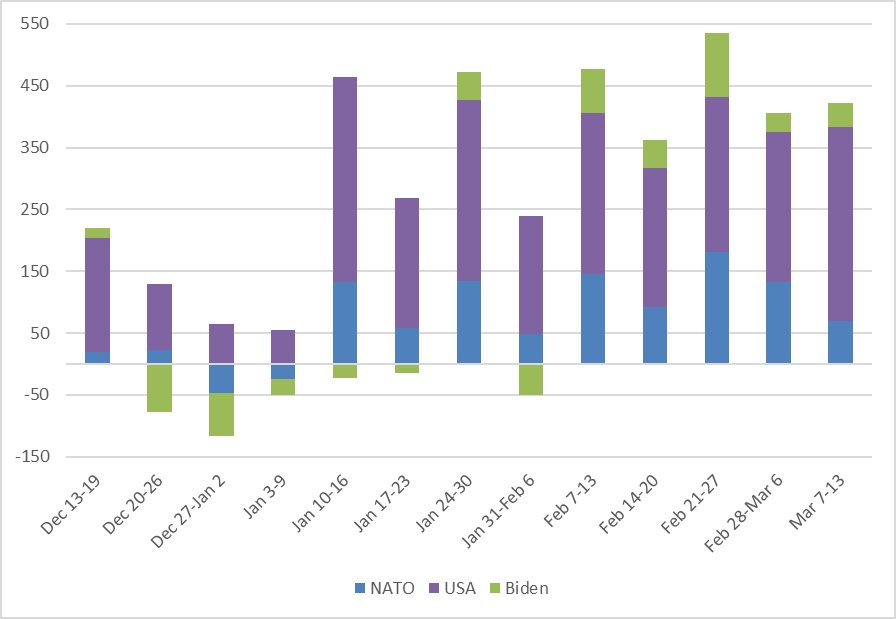

Russia’s concern for status recognition tends to feed an enduring public obsession with the United States as a rival power, which some link to Putin’s now-infamous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007. In fact, mentions of the United States are so prominent on Russian television that they compete even with mentions of Putin (Figure 5). Not surprisingly, the United States and NATO were mentioned on Russian television in roughly the same proportions during the observed period, diverging only after the start of the war (Figure 6). The ebb and flow of both mentions in lockstep is an artifact of state control.

Despite this ostensible focus on the West, Putin’s rejection of Ukrainian statehood and nationhood was already well established. His lengthy essay on Ukrainian history published in the summer of 2021 elaborated on many of his various claims about Ukraine and Ukrainians, though seemingly without any clear motivation for the timing. If there was any lingering doubt about the place of Ukraine in the Kremlin’s worldview, Putin’s televised declaration of war made it abundantly clear that his understanding of Russia’s security concerns and international status derives from neo-imperial impulses. Accordingly, one observes relatively consistent signaling of this relationship: “security” and “Ukraine” were mentioned almost equally from the start of the crisis in December through mid-January/early-February (Figure 7).

Normalizing and Decoding Talk of “War”

While the patterns of mentions on Russian television are striking, how likely is it that they were noticed by Russian viewers? Absolute counts of mentions on television do not give us a sense of the distribution of mentions throughout the day. Though pre-war surveys indicated that most Russians continued to get their news mainly from television, one cannot assume that viewers would tune in constantly or that they would even watch attentively.

To establish the extent to which a topic’s mentions rose above the background noise of everyday life, this study uses a simple measure of the number of mentions relative to the reporting of the weather. As the weather is perhaps the only thing that is reported objectively and consistently across all channels, it is a helpful measure of what constitutes normal background noise on Russian television. The assumption guiding this approach is that topics mentioned less often than the weather probably are less likely to be noticed, while those mentioned more frequently than the weather are more likely to be noticed.

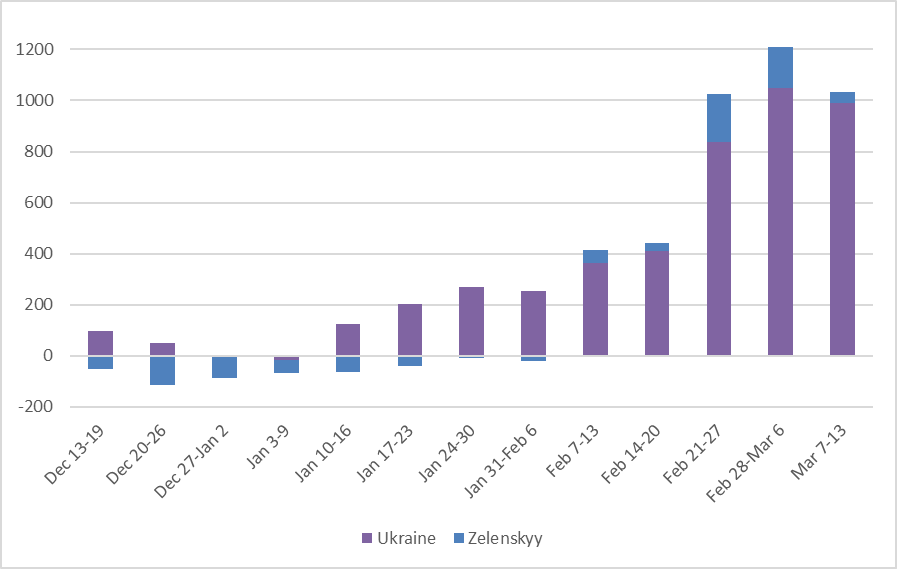

This can be demonstrated by revisiting the Russian government’s claims concerning genocide, DNR/LNR, and Nazists, for which the instrumental mobilization of these topics for Russia’s war is thrown into sharp relief: before mid-February, none of those topics warranted more mentions than the weather on Russian television (Figure 8). By contrast, the United States and (to a lesser extent) NATO were mentioned early and often from the start of the December crisis through to the invasion (Figure 9). Mentions of Ukraine barely rose to noticeable levels until mid-January (Figure 10). In the case of both Ukraine and the United States, Presidents Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Joe Biden were mentioned far less frequently than their respective countries, suggesting a framing of discourse in national terms rather than attributing policies, stances, and outcomes to the leadership of either country.

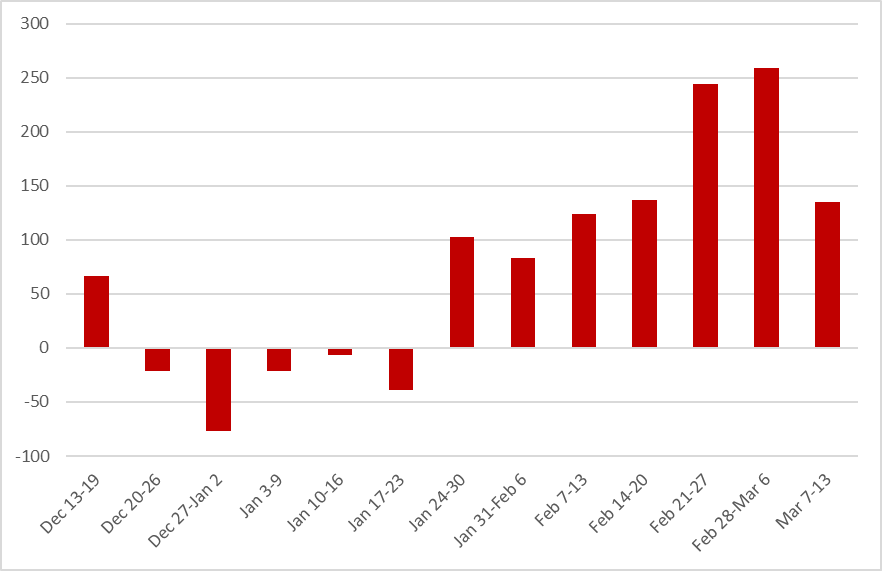

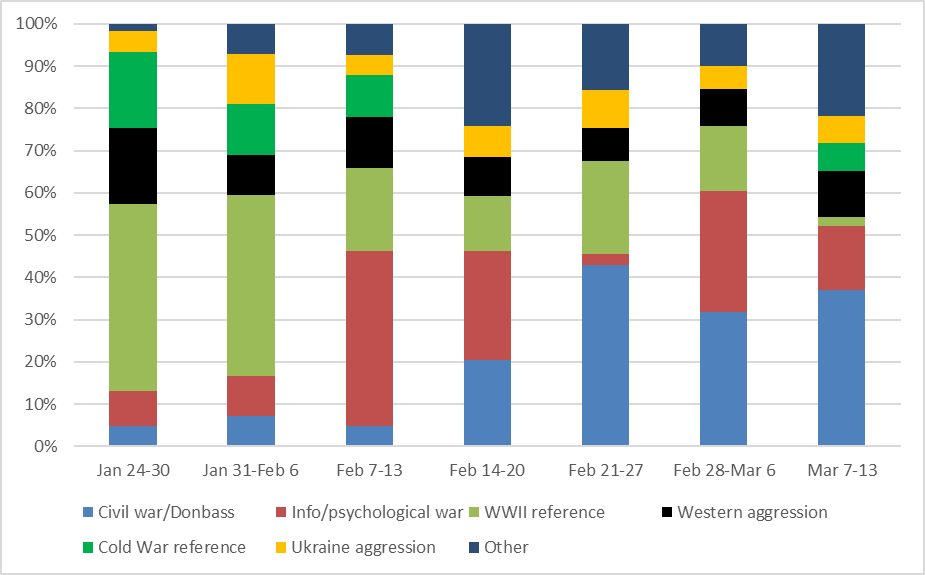

One further observes a palpable rise in the number of mentions of “war” such that it emerges from the background from late January (Figure 11). Russian TV suddenly elevated mentions of war in all sorts of ways, none of which were initially related to Ukraine. Zooming in on the various ways that war was mentioned from January 24 through March 13 (Figure 12), one observes lots of “war talk” in reference to the Great Patriotic War in mid-to-late-January. This may be considered on-brand for the Kremlin, which has turned the memory of the war into a cornerstone of the regime’s legitimation.

Historical framing was also a prevalent feature of legitimating discourse surrounding Russia’s previous military interventions in Ukraine and Syria. Also present were references to the Cold War and Western aggression (past and present) in roughly equal proportions. By February, this “war talk” expanded to include substantial mentions of information warfare, particularly in mocking the West’s “mythical Russian invasion” of Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, such references disappeared after Russia actually invaded Ukraine, to be replaced by the emphasis on the separatist republics in eastern Ukraine and the depiction of Russia’s invasion as an intervention in the “civil war” allegedly being waged against innocent, freedom-loving people in the Donbas. The speed with which Russia lost control of the online narrative about the war is reflected in the immediate re-appearance of information warfare as a priority topic on Russian television, with particular emphasis on discrediting Western social media platforms.

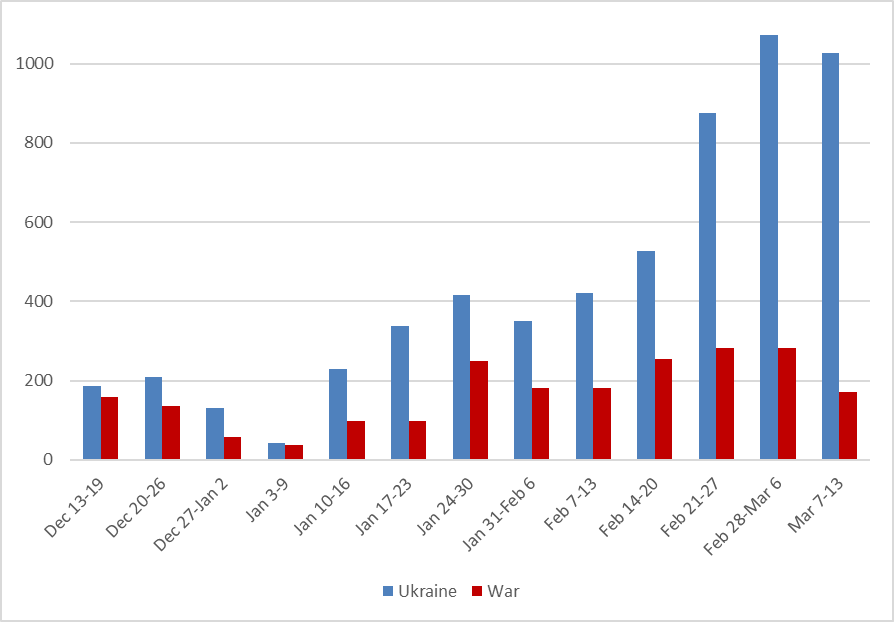

The prevalence of “war talk” in the run-up to the invasion is darkly amusing for, as is well known, the Russian government refers to its invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation.” Severe legal penalties have been introduced for those who “discredit” the Russian military or spread “fake news” by using the words “war” or “invasion.” Correspondingly, mentions of “Ukraine” on Russian television ramped up in advance of the invasion, while mentions of “war” started to build towards the end of January and then held steady through February (Figure 12).

Conclusion

This close examination of Russian television content helps to make sense of the cognitive dissonance experienced by Russian viewers following the declaration of war: while pre-war surveys by the Levada Center showed a majority of Russians to be uninterested in war, 50-60 percent were nevertheless certain that the United States and NATO would be to blame if war broke out. While pushing the United States and NATO as a security concern from the December crisis, Ukraine emerged from the woodwork on Russian television in January and took over as its main focus once the war began.

Russian television primed viewers for war with steady doses of “war talk” prior to the invasion. It reminded Russians of past victories as well as betrayals. Doing so accomplished what is known in the literature on memory politics as “chronographic suturing,“ or knitting together past and present such that people can experience a personal connection with national history through their observation of the present. For Russian viewers, state-controlled television deftly merged this “war talk” with narratives about Western and Ukrainian aggression before fully joining the war effort by advancing claims about the prevention of genocide and fighting fascism.

While there is little likelihood of displacing the central role of state-controlled television in rationalizing the war for Russian viewers, Western policy-makers should be mindful of actions that weaken countervailing voices in Russia. This is especially the case with regard to access to social media like YouTube, which are crucial alternative sources of information and income for Russian youth and opposition. Policy-makers might also consider ways to facilitate easy access to free VPNs that would allow Russians to bypass state censorship and propaganda. While these are unlikely to change domestic political dynamics in the short term, they may prove important in the longer run to ensure such spaces preserve an alternative to state-controlled media in Russia.

Figure 1: Mentions of Genocide on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 2: Mentions of Nazists on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 3: Mentions of DNR/LNR on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 4: Shifting Narratives on Russian TV, February 21 – March 13

Figure 5: Mentions of Putin and USA on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 6: Mentions of USA and NATO on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 7: Mentions of Security and Ukraine on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 8: Mentions of Genocide, DNR/LNR, and Nazists vs. the Weather on Russian TV, February 13 – March 13

Figure 9: Mentions of the United States, NATO, and Biden vs. the Weather on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 10: Mentions of Ukraine and Zelenskyy vs. the Weather on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 11: Mentions of War vs. the Weather on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

Figure 12: Associations with “War” on Russian TV, January 24 – March 13

Figure 13: Mentions of “Ukraine” vs. “War” on Russian TV, December 13 – March 13

J. Paul Goode is Associate Professor and McMillan Chair of Russian Studies at the Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at Carleton University.

[1] It is also worth noting that this time period includes the New Year’s holidays, during which one observes a dip in reporting on all topics across all channels.

[2] “Nazist” was preferred as a search term since it attributes the quality of being a Nazi to individuals, organizations, states, policies, and so forth. By contrast, searching transcripts for “Nazi” catches too many false positives as it also captures words like “national” that begin with the same sequence of letters in Russian. Moreover, the terms “fascist” and “fascism” were barely mentioned, at all, compared to the broader use of “Nazist.”

[3] Another term used to refer to the separatist republics is “Donbass,” though in broadcast it was mentioned less frequently than “DNR” or “LNR.”