The question of how state punishment is enacted in Russia is in the spotlight. The jailing of protesters and opposition leaders—emblematized by anti-war rallies, the case of Alexei Navalny, and prison abuse scandals—has led to heightened interest in criminal justice and prison systems as tools of oppression in a context of growing authoritarianism. The invasion of Ukraine, launched while writing this Policy Memo, is being accompanied by another sharp punitive turn. Draconian prison terms await those who oppose the war, and there are discussions about the reintroduction of the death penalty. When it comes to the demand for punishment, is Russia a punitive society in global terms, and who is punitive in Russia? On the supply of punishment, do state practices of punishment, and, in particular, the use of prison, match public sentiment?

We show that Russian society is, in global terms, relatively punitive in its preference for prison for offenders, but not in relation to the goal of that punishment or in attitudes to particular penal policies such as the death penalty. Preference for prison correlates with certain forms of conservatism. In terms of state policy, Russia incarcerates offenders at very high levels comparatively, yet the use of prison has been significantly declining in the last 20 years. This observation requires certain caveats. Russian prisons, according to Russian public opinion and international expert sources, remain inhumane places that succeed in inflicting pain and fail in their functions of rehabilitation, protection, and deterrence.

What Is Punitiveness, and How Can We Measure It?

We adopt a framework for punitiveness developed by An Adriaenssen and Ivo Aertsen (2015) that measures societal attitudes along four dimensions:

- Goal of punishment (retribution, protection, deterrence, rehabilitation)

- Form of punishment (incarceration, reconciliation, community sentences)

- Intensity of punishment (length of sentences, size of fines, strictness of prisons, alternative sanctions)

- Attitudes to specific policies (political disenfranchisement for felonies, death penalty, possibility of parole)

To investigate attitudes in Russia along these dimensions, we utilize results from a nationally representative survey we conducted in 2019 that combined questions about punitiveness as well as broader social values as part of a broader investigation of the culture of punishment in Russia and Kazakhstan. In looking at the supply side of punishment, we use the prison rate—how many people are held in confinement per one hundred thousand of the population—taken from the World Prison Brief, a respected resource that tracks prison populations across the globe. The prison rate is undoubtedly a flawed measure since it does not foreground prison conditions or the length of prison sentences. It does, however, provide a rough overall proxy for measuring changes in the myriad political responses to crime. First, a look at the demand side.

Demand Side: Popular Punitiveness

Goal of Punishment

Our survey shows that, in terms of incarceration, Russians believe that prisons should protect the public, deter crime, and rehabilitate offenders. Few respondents think that offenders should be treated harshly or differently from other people. Table 1 shows the percentage of respondents “strongly agreeing” to questions about the purpose of prison:

Table 1. Punitive Goals

| Purpose of punishment | Statement | “Strongly Agree” |

| Protection of the public | Prison should isolate prisoners from society | 32 percent |

| Infliction of pain | Offenders should be treated harshly | 13 percent |

| Rehabilitation | Prison should help prisoners become law-abiding | 39 percent |

| Deterrence | Prison should deter others from committing a crime | 44 percent |

Respondents do not necessarily think that their prisons perform these desired functions particularly well, however, as Table 2 below shows.

Table 2. Societal Performance

| Performance of punishment | Question | “Very well” |

| Protection of public | How well does prison isolate prisoners from society? | 15 percent |

| Rehabilitation | How well does prison help prisoners become law-abiding? | 7 percent |

| Deterrence | How well does prison deter others from committing crime? | 13 percent |

In contrast, respondents perceive Russian prisons as effective at inflicting pain on offenders, as Table 3 shows.

Table 3. Treatment Performance

| Performance of Punishment | Question/Statement | “Strongly Agree” |

| Prison conditions | Prisoners have too easy a time of it in prison | 6 percent |

| Effect of prison on offenders | Most people come out of prison worse than when they go in | 23 percent |

| Treatment in prison | How good are prisons at treating prisoners like normal human beings? | 6 percent (“very good”) |

Form of Punishment

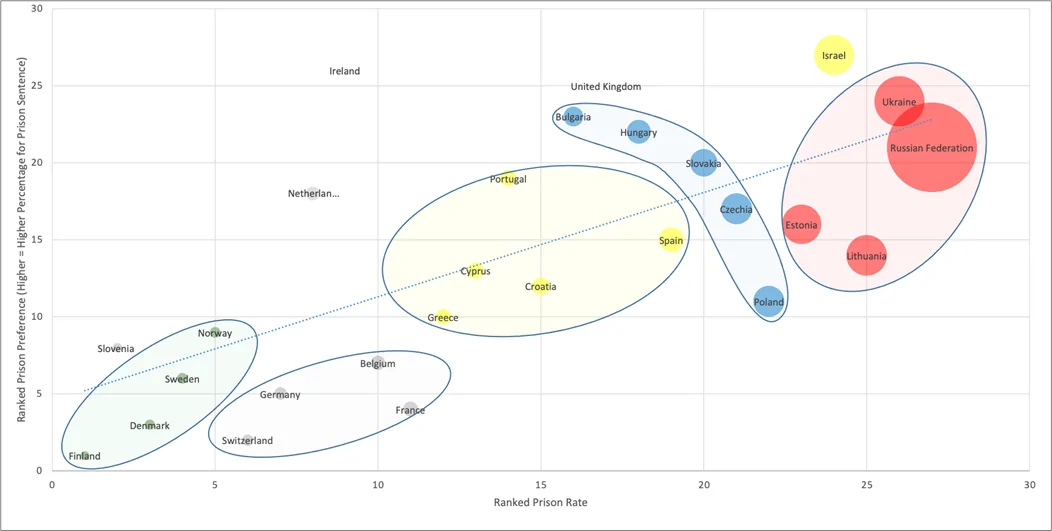

Given that Russians are against prison inflicting pain yet believe that this is the only thing prisons do efficiently, it is perhaps surprising to find that respondents have a strong preference for sending offenders to prison. When asked whether all convicted offenders should be given a prison sentence, 56 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed. Provided with a vignette of a 25-year old man convicted of burglary for the second time, 80 percent of respondents would pass a prison sentence rather than a suspended sentence, fine, community sentence, or other punishment. This figure puts the preference for prison in Russia at around twice the global average compared to responses to a similar question in the various International Crime and Victimization Surveys (ICVS) conducted around the world. It is around 20 percent higher than the European average in response to the exact same question in the 2010 European Social Survey (ESS).

Societal-level predictors of preferences for prison in the ICVS data include high levels of crime and inequality—both characteristics of Russian society. Yet, Russians’ prison preference is higher than in countries such as Mexico (60 percent prison preference), where the problems of crime and inequality are just as, or even more, acute. Other post-communist countries in the ESS score highly in prison preferences, so it may be that the high prison rates of communist regimes produced a normalization of imprisonment as a default response to crime in these countries (see further below). It is also worth noting that the figure of the “thief-recidivist” is a cultural trope in Russia connected to organized crime, so the supposedly neutral ICVS and ESS vignette might inadvertently trigger a severe reaction in Russian respondents.

Intensity of Punishment and Specific Penal Policies

Of the 80 percent of respondents in our survey who would send the offender to prison in response to the above vignette, 37 percent would make the sentence five years or longer. In this vein, respondents also reported a preference for the courts to pass down harsher punishments for offenders. Around 37 percent of respondents think that sentences are too lenient compared to 36 percent who think they are about right, and 27 percent who think sentences are too harsh. It is not clear if a harshening of sentences would translate as a preference for more and longer prison sentences, though this seems like a safe inference given responses to the question about recidivist burglars.

In terms of specific penal policies, attitudes to capital punishment are often considered a good proxy for punitiveness more generally. Since 1999 there has been a full moratorium on the use of the death penalty in Russia. The moratorium is often seen as a policy that contradicts public opinion. Indeed, at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the death penalty for the crime of murder was, according to the International Social Survey Programme, more popular in Russia than anywhere else in the world with the exceptions of Hungary and the United States (73, 78, and 75 percent agreeing or strongly agreeing, respectively). Fast forward to today, and Russian support for the death penalty as a suitable punishment for murder has dropped faster than in, say, the United States. In 2019, 49 percent of Russians were generally supportive of the use of the death penalty for murder compared to 60 percent of Americans in the 2018 General Social Survey.

Who is Punitive?

With which social values does punitiveness correlate? A principal component analysis of responses to moral values items taken from the World Values Survey shows three interrelated latent variables for conservatism: attitudes to traditional families and work; patriarchal attitudes; and attitudes to minorities such as migrants and LGBTQ+ people. Correlating these variables with our survey’s ten-item index covering the four theoretical components of punitiveness discussed above, we find that traditional attitudes towards family and work correlate positively and relatively strongly with punitiveness. But patriarchal conservatism does not. Surprisingly, xenophobic and homophobic attitudes are actually negatively correlated with punitiveness, though the relationship is weak. In terms of policy preferences—using government spending preferences taken from the International Social Survey Project (Role of Governance)—we find a preference for public spending on national defense correlates positively with almost all punitive variables. However, interestingly, there is no clear relationship between punitiveness and the preference for more spending on law enforcement.

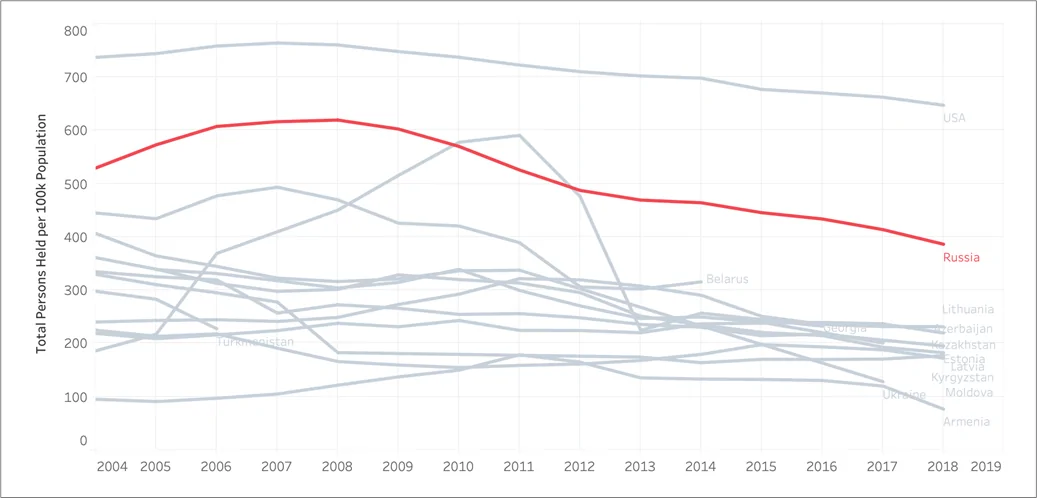

Supply Side: Punishment Trends in Russia

The Russian Federation has maintained historically high incarceration rates in global terms. Throughout the 1990s, for example, Russia held more prisoners per capita than anywhere in the world, with the exception of the United States. Today, at 322 per 100 thousand persons, Russia’s prison rate is nearly half that of the United States, and the trend is downwards: From 2000 to 2018, Russia’s prison rate declined by 45 percent (see figure below). The overall prison population fell from over 1,000,000 prisoners in 2000 to 466,000 prisoners in 2022. This occurred alongside only moderate decreases in contact (arrests) rates, suggesting that the drop in prison numbers is not the product of declining detected crimes. Instead, the massive amnesties in 2000 and 2001 (which released a quarter-million prisoners), liberalization of the criminal code, the prosecutorial diversion of offenders from the court system, and a less punitive judiciary that more than halved the number of defendants sent to prison each year (from 380,000 in 2000 to 150,000 in 2020), are behind the trend.

Figure 1. Persons Held per 100,000

The prison population reduction does not apply to all types of prisoners: Memorial reports an increase in the numbers of political prisoners between 2020 and 2021. Moreover, despite the decline, Russia still has by far the highest prison rate of all Council of Europe members, a rate three times higher than the EU average. In comparison with other CoE countries, Russia has a prison death rate almost twice the average, spends the least per prisoner and has the highest prisoner-to-staff ratios. While prisoner numbers are decreasing, prison conditions are not improving.

What is the relationship between public punitiveness and the prison rate? In the figure below, we take incarceration rates for the year 2010 from the World Prison Brief, ranking countries according to their scores (lowest to highest), and plot these rankings against ranked scores of percentages of respondents choosing prison for a 25-year-old second offense burglary in the 5th Wave ESS (2010). Countries with similar histories and cultures tend to cluster together. Post-Soviet countries form one such cluster, exhibiting the greatest demand and supply of punishment in Europe, with post-communist eastern European jurisdictions clustering nearby. Russia’s prison rate correlates with prison preferences in the population.

Figure 2. Worlds of Punitiveness

However, in the ten years since the 5th Wave ESS was conducted, Russia’s prison rate has started to diverge from popular prison preferences. Criminologists in Western democracies have long theorized, and in some cases demonstrated, that public opinion is a driver of penal policy. In democracies, politicians compete electorally over who can meet the demand for law and order. Authoritarian leaders, in contrast, have a different set of incentives. Many former Soviet jurisdictions where authoritarian trends have been evident in the past twenty years—Belarus, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, for example—have conducted some of the deepest and quickest cuts to prison rates in the region. A theory of authoritarian prison downsizing is called for.

Conclusion

While Russia remains a punitive state—proxied as it is here—with a peculiar relationship to the practice of incarceration, this relationship is changing. Russians no longer stand out globally in their support for the death penalty. Russians do not want prisoners to undergo poor conditions or inhumane and harsh treatment while serving prison sentences. They understand that Russian prisons remain cruel institutions that make people worse and fail to protect, deter, or rehabilitate. On the other hand, in global terms, Russians still have a very strong preference for sentencing criminals to prison terms—at least as a go-to option. This is in conflict with state policy—the overall prison rate has been in decline for 20 years; fewer people are in prison in Russia today than at any time since the Soviet Union disappeared.

While the declining prison rate should be welcomed and encouraged by the international community, it must not deflect from the failures of the prison system evident to ordinary Russians—high recidivism rates (60 percent), continued inhumane treatment of prisoners, regular cases of torture, and poor prison conditions. Moreover, policymakers should recognize that authoritarian penal policy is driven by an executive that can easily reverse the prison rate trend as and when a populist leadership finds it expedient to realign state punitiveness with popular sentiment. Our findings, as concerns the relationship between various measures of social values and punitiveness (forthcoming), further suggest a much more complex relationship between concepts of punitiveness, conservatism, and other attitudes within Russian society than has been previously reported.

Daniel Horn is Research Associate in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Strathclyde.

Gavin Slade is Associate Professor in the School of Sciences and Humanities at Nazarbayev University.

Alexei Trochev is Associate Professor in the School of Sciences and Humanities at Nazarbayev University.

This research was carried out as part of a project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK (No. ES/R005192/1).