(PONARS Policy Memo) In the 1990s and early 2000s, much of Russian politics revolved around relations between the Kremlin and regional elites. As Putin recentralized federal authority over the course of the 2000s, these relations became less important. However, recent developments suggest that Russia watchers should keep their eye on regional politics. Certain trends in subnational appointments—in particular, the increasing number of governors who have few ties to their regions—may undermine the ability of the regime to mobilize votes. Moreover, recent political reforms, such as the reintroduction of gubernatorial elections and single-member-district deputies in the Duma, combined with the increasing use of arbitrary repression against regional officials, have the potential to undermine elite cohesion, which has long been one of the key pillars of regime stability in Putin’s Russia.

Subnational Appointments

Russia’s regional governors have been de facto appointed since 2005.[1] Since that time the Kremlin has mostly outsourced the task of mobilizing votes to regional leaders, and rewards those who perform well. Indeed, political science research shows—and Kremlin insiders confirm—that regional governors are evaluated, in large part, on the basis of how well they do at mobilizing votes for United Russia. Regional governors have been adept at mobilizing voters because they built powerful political machines over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s. Recognizing the electoral importance of regional patrons, the Kremlin was slow to replace powerful governors when it canceled elections in 2004. Most governors remained in place, and when governors were replaced, they were usually replaced with regional insiders.

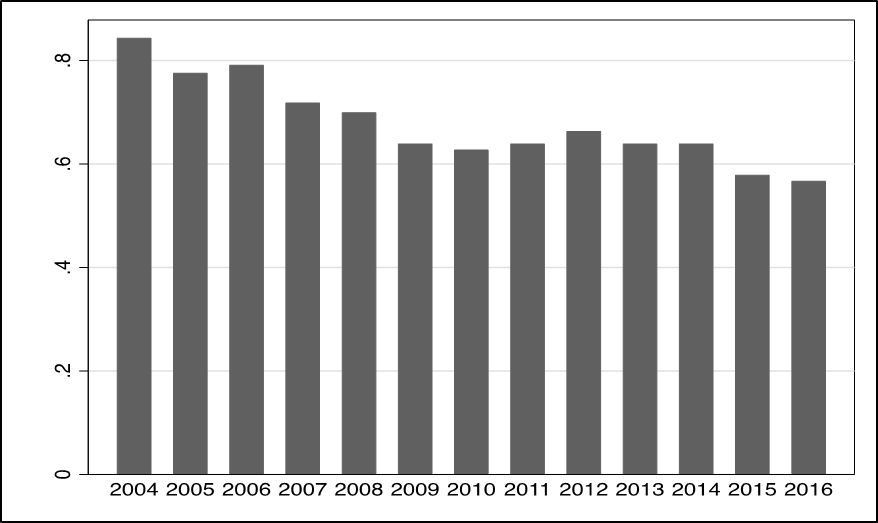

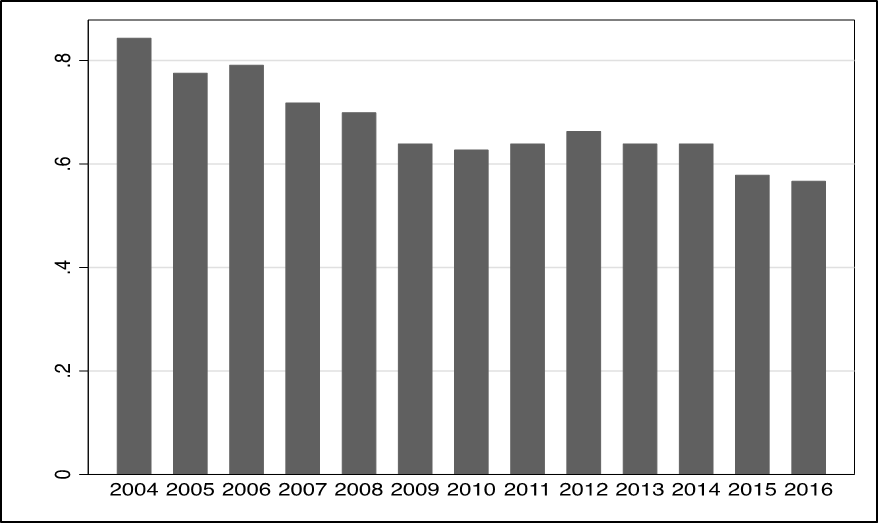

Nonetheless, as Figure 1 shows, the share of governors with pre-existing ties to their region, while still more than half, has been declining over time. Outsider governors are usually businessmen, federal bureaucrats, or, more rarely, siloviki. Moreover, appointments in 2016, though few in number, were marked by an even more drastic shift in favor of outsider governors. As Figure 2 indicates, governors with direct professional links to Putin have been a rarity, but four of the eight governors appointed in 2016 were direct clients of Putin and had no ties to the region.

The Kremlin’s preference for regime insiders over regional politicians is understandable. An official whose political qualifications consist solely of their ties to regime leaders is more likely to remain loyal in trying times. By contrast, those with autonomous resources, such as a pre-existing regional power base, will find it easier to craft a political future after a transition, and indeed, may even be able to remain in their position as governor. This reduces their incentive to remain loyal.

But this practice has clear electoral drawbacks. Replacing popular local politicians with bureaucrats risks undercutting the Kremlin’s own mobilization strategy. Indeed, studies show that United Russia tends to perform better in regions where the governor is popular and where the governor has strong ties to the region. Experience in the region gives insiders a number of advantages over outsiders including better information, pre-existing client networks, public support and ties to local elites.

These trends coincide with the cancellation of direct elections in Russia’s major cities. By 2015, 66 percent of Russia’s large cities had replaced directly elected mayors with appointed city managers (technocrats with limited electoral experience). In addition, as legislative elections in Russia’s regions have become less competitive, fewer and fewer pro-regime legislators have experience running a real election campaign.

The net result of these trends is that officials in the regions are increasingly lacking in electoral experience. In the 1990s and 2000s, regional politicians cut their teeth on electoral campaigns that were sometimes quite competitive. Those who won the most votes—either through their own political machines, charisma, or electioneering skills—were elected. The Kremlin then co-opted those politicians and enlisted their electoral skills in its own voter mobilizing efforts. By canceling elections at various levels—or making them less competitive—the regime is creating an entire cohort of regional officials that have few voter mobilization skills.

Since 2014, the regime has been coasting on Putin’s astronomically high popularity ratings, but should those ratings ever dip, the regime may find it difficult to mobilize votes in the regions, a problem that surfaced during the 2011 State Duma elections. Indeed, turnout has already been on the decline in recent elections. For the past several years, the regime has sought to depoliticize electoral contests and puts little effort into mass mobilization. This is especially true in urban areas, where regime support is the lowest and has been shrinking. Instead, the regime is increasingly relying on state-dependent voters, especially in rural areas. The regime still wins large legislative seat shares, but low turnout victories are not as impressive as those with high turnout. Low turnout undermines the legitimizing function of elections. Moreover, low turnout deprives the regime of crucial information about the distribution and content of social grievances.

Elite Cohesion

Two of the most common causes of autocratic breakdown are elite defections and mass uprisings. Given the headline-grabbing nature of the 2011-2012 series of protests, most research on Russia has focused on the former. Yet recent years have witnessed several dynamics that should lead observers to pay more attention to elite cohesion in Russia’s regions.

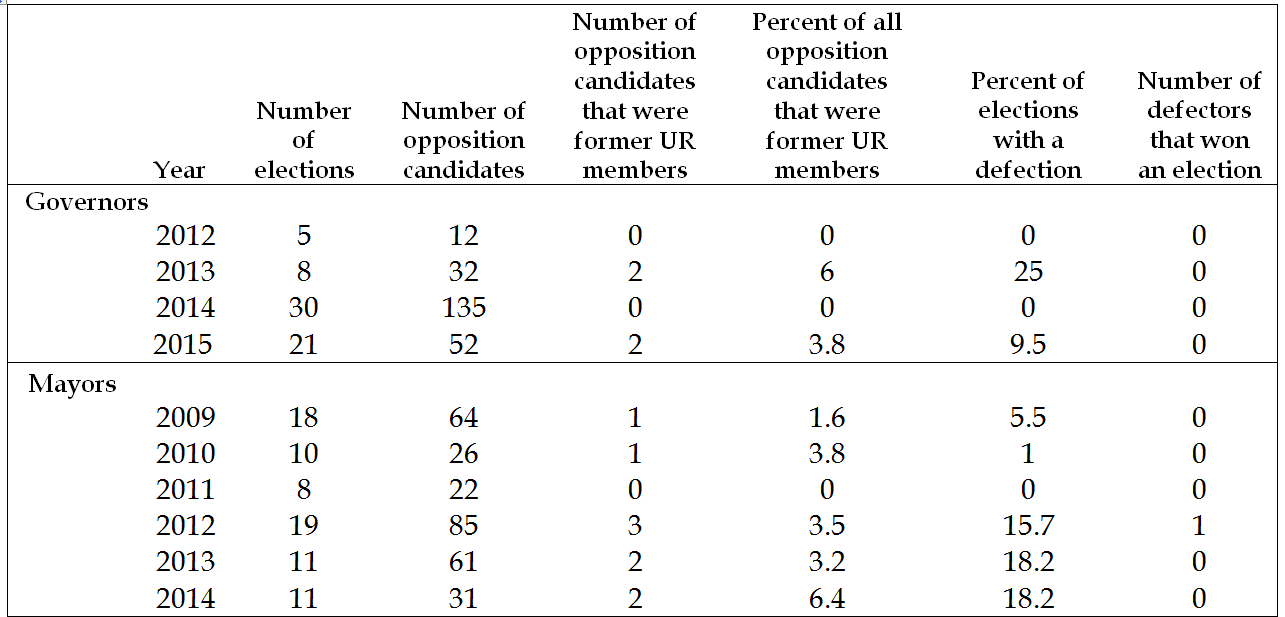

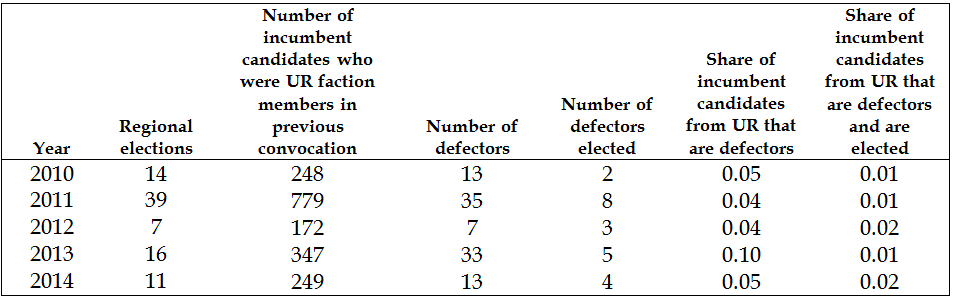

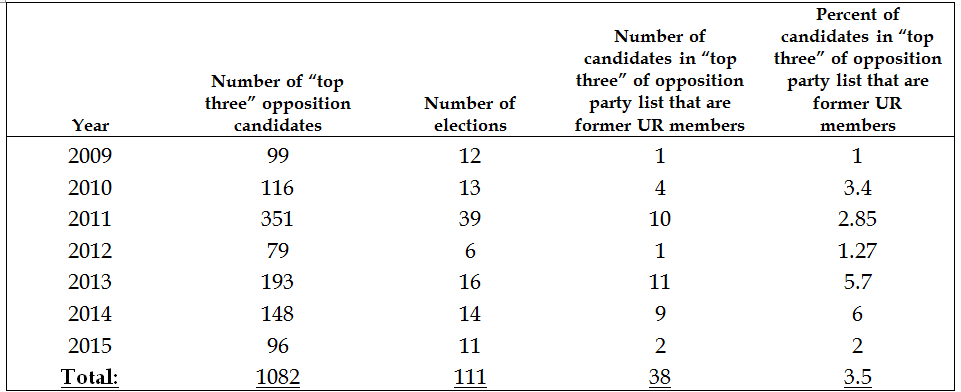

Elite cohesion has been one of the Putin regime’s strongest pillars. One technique political scientists use to measure elite cohesion is to look at how many opposition candidates are defectors from the ruling party. As Tables 1-3 show, the number of defections in Russian regional elections has been quite low. Nevertheless, the data do indicate that there was an uptick in defections in 2013 when Putin’s popularity reached its lowest point. Elites in electoral authoritarian regimes are prone to herd behavior. When the popularity of regime leaders declines, authoritarian regimes can experience sudden cascades of defections. The regime avoided this outcome in 2011-2013, but once the post-Ukraine consensus fades, Putin’s popularity will likely sag again. If it drops lower this time, analysts should look for defections by regional elites as a warning sign of regime collapse.

This is especially relevant because several recent developments could make it more difficult for the regime to maintain elite cohesion in the future. The reintroduction of single-member districts (SMDs) for State Duma elections has weakened Untied Russia’s control over its faction members. The reintroduction of the SMD component is also risky because it strengthens regional governors. In the 1990s, regional governors expanded their political power by packing the Duma with clients, mostly via SMD races. The 2016 elections saw a resurgence of this practice.

The reintroduction of gubernatorial elections could also undermine elite cohesion, especially during a potential crisis. The Kremlin has kept tight control over gubernatorial elections, and Putin retains the right to remove governors from office. This, quite obviously, limits the autonomy of regional governors. Nevertheless, today’s governors do have popular mandates, an autonomous resource that they lacked for much of the 2000s. If economic stagnation continues and/or Putin’s rating falls, it is not inconceivable that one or more governors might use their electoral legitimacy as a platform to oppose the Kremlin.

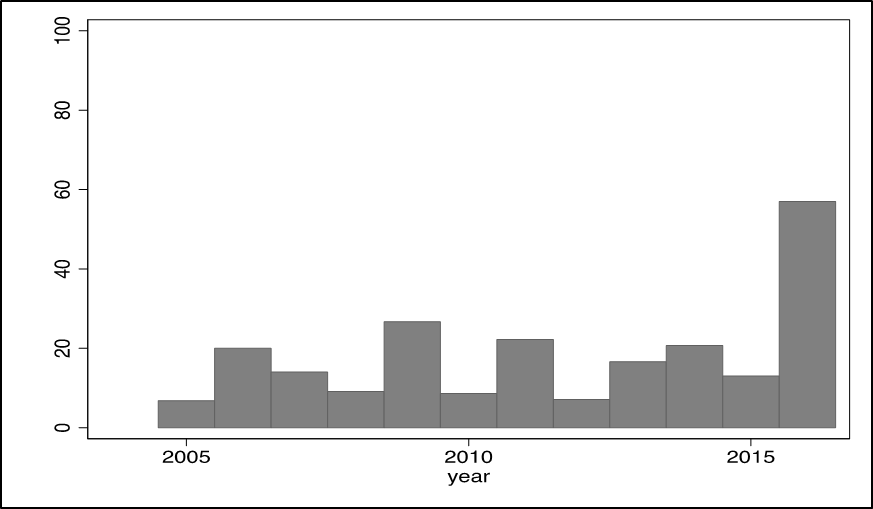

Finally, an increasing tendency to use repression against regional officials may undermine elite cohesion. The past several years have witnessed a precipitous increase in arrests of high-level regional officials, usually on corruption charges. While criminal cases against opposition politicians and former regime officials have been common for over a decade, recent years have seen a dramatic uptick in arrests of sitting, pro-Kremlin officials. Several of these arrests have been accompanied by dramatic public relations stunts, in which the official is arrested while at work or in compromising situations. In 2015 and 2016, four governors, six vice governors, and sixteen mayors of large cities were arrested while in office. And while it is difficult, if not impossible, to divine the causes of individual arrests, the pattern appears highly idiosyncratic.

The seeming randomness of these arrests has generated uncertainty among the regional elite. The implicit arrangement that has existed between Putin and regional elites for much of the last 15 years has been one of mutual gain and clear expectations. Regional officials were expected to be loyal and mobilize support for the Kremlin. In return, they received career advancement opportunities and political backing from the Kremlin. The random application of repression has the potential to upset such an arrangement; after all, elites have little reason to remain loyal if they cannot be sure that loyalty will be rewarded.

In some ways, the two trends identified above are countervailing. Increasing incentives for elite defections may be offset by the increasing number of regime loyalists who have been appointed. Indeed, one cannot exclude the possibility that this is by design. Nonetheless, we should not overstate the number of outsiders serving as governor. The fact that over 50 percent of governors are still regional insiders means that there are a large number of governors that are not Putin’s direct clients.

Federal autocracies are more likely to break down when regional elites defect, as recent experiences in Mexico, Nigeria, and Venezuela illustrate. In all these cases, electoral collapse at the federal level was preceded by defections and electoral failures in the regions. The data and discussion above indicate no signs of immediate unraveling in Russia, but beneath the surface, a number of challenges are brewing. Students of Russian politics should pay attention to these developments.

Figure 1: Share of Sitting Governors with Significant Work Experience in the Region Where They Serve*

*On December 31st of each year. A governor is deemed to have “significant” work experience in the region if a plurality of their post-university careers were spent in the region.

Figure 2: Share of Governors Appointed Each Year with Direct Professional Ties to Putin*

*Note that this figure does not indicate the yearly share of sitting governors with professional ties to Putin. Each bar indicates the share of governors appointed in a given year that have ties to Putin. A governor is coded as having professional ties if he or she worked with or under Putin, either before or after Putin became president. Any federal officials who were appointed by Putin are coded as having worked under Putin.

Table 1: Defections from United Russia in Gubernatorial and Mayoral Races, 2009-2014

Table 2: Defections from United Russia in Russian Regional Legislatures

*Data is from the Russian Central Election Commission (www.cikrf.ru) and the author’s Database of Russian Political Elites.

Table 3: United Russia Defectors Among Top Opposition Candidates in Regional Legislative Elections, 2009-2015

Source: Author’s Database of Russian Political Elites.

[1] Direct elections were reintroduced in 2012, but the president retains the right to fire governors and appoint interim replacements. Since 2012, the practice has been for the president to name an interim governor months before the election—even if that interim governor is the incumbent—and the interim governor then wins in a landslide. In this way, Russian governors are still effectively presidential appointees.

Ora John Reuter is Assistant Professor of Political Science at University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

[PDF]