(PONARS Policy Memo) Disagreements between Russia and the United States on how to counter violent extremism and terrorism are long-term and objective in nature. These stem from fundamentally different political systems, cultures, values, historical experiences, national interests, and global roles that are unlikely to disappear anytime soon. However, even as bilateral relations have deteriorated sharply since 2014 between the United States and Russia, these two countries have experienced increasing convergence in the types of terrorist challenges they face, the overall levels of threat terrorism poses to their homelands, and the contexts in which each country operates when countering terrorism and violent extremism. Not only is there a mutual interest in addressing violent extremism in Syria/Iraq and Afghanistan, but new ways have emerged to share good practices for combating homegrown extremism and radicalization.

Comparative Threats from Violent Extremism

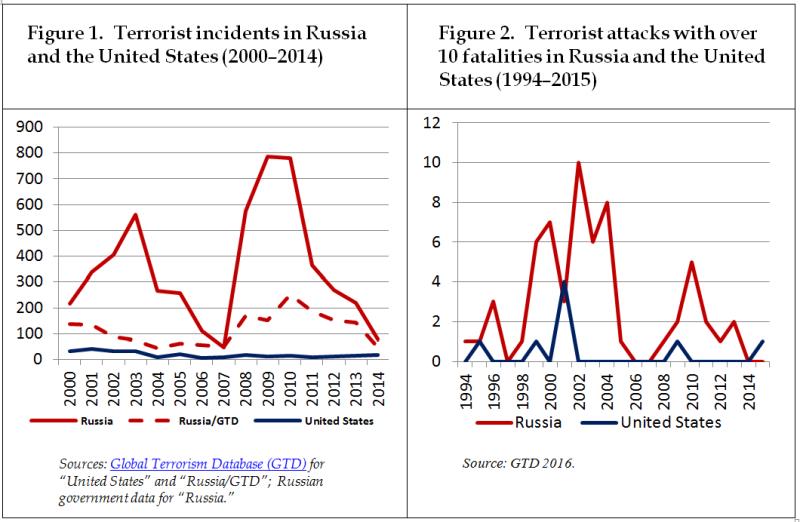

The threats posed to Russia and the United States by violent extremism and terrorism differ in type, scale, drivers, and radicalization paths. For the first quarter century after the end of the Cold War, Russia was more systematically and heavily affected by terrorism at home than was the United States (see Figures 1 and 2). This is primarily because the Islamist/separatist insurgencies in the North Caucasus have employed terrorism as one of their main tactics.

During the same period, the United States homeland has had limited exposure to terrorism (if one excludes the notable “outlier” of the 9/11 attacks). Throughout the early 21st century, Russia systematically ranked far higher than the United States in the Global Terrorism Index (GTI). For the first decade after 9/11, Russia was in the top 10 (2002-2011) of states “most impacted by terrorism.” It later fell down to 11th place in GTI 2014 (which covered 2000-2013) and 23rd place in GTI 2015 (2000-2014). In contrast, the United States ranked 41st during 2002-2011, 30th in GTI 2014, and 35th in GTI 2015. More recently, however, the respective levels of terrorist threat to homeland have become increasingly comparable: according to GTI 2016 (2000-2015), Russia ranked 30th and the United States 36th. In global perspective, U.S. interests and presence remain the primary foci of transnational terrorist networks, who frequently attack or threaten them abroad. America’s overall exposure to international terrorism, as reflected by U.S. State Department and Treasury Department terrorist lists, is thus much broader and more global compared to Russia.

Radical Islamist groups strongly dominate both the U.S. and Russian lists of terrorist actors. As of November 2016, 21 of 26 organizations on Russia’s list were Islamist, as were 43 out of 61 on the U.S. State Department’s list of “foreign terrorist organizations.” These lists have only minimally overlapped (even as that overlap somewhat increased in the recent years), the result of divergence in the type of terrorist threats each country mainly faces, the scale of interests involved, and differences in global military presence. There have been only two times when the U.S. and Russian lists have overlapped on more than one group in the same region. The first was the overlapping listing of al-Qaeda and the Afghan Taliban in 2006–2010.[1] The second took place in the mid-2010s with the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIS, also referred to as ISIL, IS, and Daesh) and the Al-Nusrah Front (Jabhat an-Nusrah).[2] Indeed, despite major policy disagreements on Syria and support for opposite sides in the Syrian civil war, it is on the Syria/Iraq context that the U.S. and Russia’s antiterrorism agendas overlap most closely.

ISIS in particular, as an ideology and a catalyst for Islamist violent extremism, has posed a domestic and foreign policy challenge to both the United States and Russia. Both countries share concerns about transnational two-way flows of militants. Russia is more heavily and directly affected by this: as of September 2015, only 21 U.S. citizens had joined ISIS and Jabhat an-Nusrah in Syria and Iraq (43 more Americans planned this or tried, but failed). For reasons ranging from lack of geographical proximity to the generally lower degree of radicalization of American Muslims, the U.S. numbers are miniscule compared to the 2,900 militants from Russia who fought in Syria and Iraq at the end of 2015. (Of note, 5,000 jihadists joined ISIS from the EU.)

For the United States, the ISIS challenge is a combination of the Iraq quagmire, broader Middle Eastern predicaments, and concerns over ISIS influence and propaganda spurring homegrown violent extremism. Regarding Iraq, ISIS has been seriously undermining its stabilization at a time when the country has been struggling with the aftermath of the U.S. intervention, bad governance, and sectarianism. Regarding the broader Middle East, ISIS has been fueling pan-regional destabilization, catalyzing regional rivalries, impeding a solution to the Syrian crisis, and spawning copycat groupings.

In the 15-year period after 9/11 (through November 2016), U.S.-based deadly terrorism was dominated by two types of violent actors: right-wing radicals (18 attacks resulting in 48 fatalities) and Islamist extremists (10 attacks resulting in 94 fatalities). While homegrown Islamist terrorism was less frequent than right-wing terrorism, it was 3.5 times more deadly and was gradually increasing in lethality, including accounting for the deadliest attack on U.S. soil since 9/11: the June 2016 Orlando Night Club shooting that killed 46 people. U.S. homegrown Islamist terrorism has been primarily perpetrated by small cells or individuals (“lone wolves”) with few, if any, direct links to foreign terrorist organizations. These often do, though, act under the influence of transnational radical ideologies and movements such as al-Qaeda or ISIS.

For Russia, the domestic implications of the ISIS challenge have not been confined to the North Caucasus, including the return of jihadists from Syria and Iraq and pledges of loyalty to ISIS by local militant underground units. Beyond this region, ISIS has catalyzed a new phenomenon of small radicalized homegrown cells or individuals across Russia, but with limited or no direct link to the North Caucasus. While distinct from the North Caucasian insurgency, these actors are increasingly similar to the type of homegrown violent Islamist extremists faced by the United States, ranging from lone wolves to violent extremist network agents.[3] Russia is experiencing increasingly direct parallels to the United States in this type of fragmented homegrown violent extremism, inspired by transnational influences and ideologies. This is an already well-embedded pattern in the West, but a more recent phenomenon for Russia. Also, the decline in Islamist-separatist terrorism and insurgency in the North Caucasus has been paralleled by growing visibility of right-wing extremism in Russia (increasingly directed against migrants). The violent manifestations of this phenomenon have usually come in forms other than terrorism, including scuffles, provocations, ethnic/religious vandalism, pogroms, and disturbances.

Comparative Strategies to Countering Terrorism and Violent Extremism

For much of the early 21st century, both American and Russian antiterrorism strategies have been heavily militarized and dominated by the “war on terror” paradigm. The context for these strategies, however, differed radically. Russia waged domestic counterinsurgency campaigns in the North Caucasus while the United States led overseas security involvements ranging from military interventions to stabilization/counterinsurgency operations in failed, weak, and seriously fractured states such as Afghanistan and Iraq. Consequently, Russia’s main antiterrorism “solution”—even if costly and incomplete—has been domestic reliance on traditionalist ethno-religious forces inside Chechnya as a hedge against, and a more manageable alternative to, transnationalized violent Salafist jihadism—at the expense of tolerating autocratic tendencies, a questionable human rights record, and a re-Islamicization agenda. It is only Russia’s campaign in Syria (since 2015) that has displayed at least a typological similarity to the US-led coalition operations overseas (against ISIL in Iraq starting in 2014 and then extended to Syria). In both the North Caucasian and the Middle Eastern contexts, the relevance of Russia’s antiterrorism experience to the United States, and vice versa, has been severely limited for ideological reasons. An example would be Washington’s strong emphasis on a democratization agenda in (post)conflict settings, regardless of the context and feasibility, and low tolerance for “dictators fighting extremists” solutions.

In the past few years and to different degrees, both the US and Russia have moved beyond heavily militarized (counter)terrorism-centered strategies and toward approaches that are more comprehensive, though for different reasons that complicate comparison. In the United States, a paradigm shift occurred from the “war on terror” to “countering violent extremism” (CVE) under the less securitized Obama administration. This move was dictated by mounting problems and the increasingly compromised antiterrorism agenda associated with a) U.S. intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq, b) international and regional developments such as the Arab Spring, and, to an extent, c) the rise in fragmented homegrown violent extremism in the U.S. homeland. This paradigm shift, at least at the level of U.S. political discourse, has no direct parallel in Russia. Russia’s heavily securitized antiterrorism agenda and discourse have not become as controversial or politically compromised. Instead, they remain one of the keys to the success Putin’s regime, whose significant public support has been reinforced as the ISIL factor in and beyond the Middle East has sparked fears that transnational Islamist extremism can spread. Thus, the evolution of Russia’s approach has not involved a conceptual shift from counterterrorism to CVE. Rather, within its current approach, there is some growing attention being paid to causation and non-military aspects of antiterrorism (political, socio-cultural, and developmental).

Comparative analysis of the American and Russian approaches to CVE reveals two paradoxes. First, despite the (typologically and geographically) narrower character of the main violent extremist threat to post-Soviet Russia (linked to domestic Islamist/separatist insurgency), Russia’s definition and interpretation of extremism is far broader than the U.S. notion of “violent extremism.” Russia employs a very broad and blurred category of “extremism” that embraces all internal and external activity, violent and non-violent, anything aimed at “breaking the unity and territorial integrity” or “destabilization of the domestic and social situation.” Second, while Russia’s territory has been more systematically and heavily affected by terrorism/violent extremism than the U.S. homeland, the United States shows greater interest in CVE-type preventive, counter/de-radicalization, “soft security” initiatives (distinct from coercive law enforcement measures) at home than Russia does.

The two countries’ approaches to counterextremism also exemplify fundamental differences in their respective dominant normative/value systems. In advancing counternarratives to those put forth by extremists, the U.S. emphasis is on a community-based, democratic civil society response while Russia’s is on actively “promoting ethnoconfessional tolerance” and “spiritual, ethical and patriotic values” traditional to Russian culture.

While these nuances and gaps are important, they should not be absolutized. Nor should one overestimate the American emphasis on CVE. The Obama administration’s CVE focus is not likely to be reproduced or prioritized by the Donald Trump administration. Also, in practice, it did not radically affect funding priorities for counterterrorism, nor did it change the U.S. reliance on military/security operations overseas as a way of reducing terrorist threats to the American homeland. Russia may not emphasize domestic CVE the way the United States does, but, in practice, the United States has not excessively emphasized it either. Nor should any conceptual gaps prevent the two countries from sharing good practices in preventing and countering violent extremism, including terrorism, and learning from each other’s comparative strengths and weaknesses—especially as the two cases are becoming more comparable, not less.

Pathways for Cooperation

Since 2014, most institutionalized security mechanisms for U.S.-Russian cooperation on countering terrorism and violent extremism have been cancelled or suspended by the United States in response to Russia’s actions vis-a-vis the Ukraine crisis. Halted were the two Working Groups of the Bilateral Presidential Commission, one led by diplomats and the other consisting of senior intelligence officials. The same goes for Russia’s cooperation with the United States/West in multilateral security formats such as the NATO-Russia Council or G-8 Counterterrorism Action Group. Some contact and cooperation channels continued, such as low-profile intelligence-sharing between security agencies, and joint work on some UN (and UN-related) initiatives, such as the UN Security Council resolutions on foreign militants and terrorism financing in Iraq and Syria, and at the Global Counterterrorism Forum.

In a situation when most institutional cooperative frameworks have been cancelled or suspended, and most of them may not even be revivable, there are at least two main directions that the United States and Russia could and should pursue, to mutual benefit, in order to counter terrorism and violent extremism more effectively.

The first direction is to move from the heavy and almost exclusive focus on counterterrorism (which was in past cooperative frameworks) toward paying at least as much attention to countering and preventing violent extremism and radicalization. The focus on CVE highlights a growing parallel need—as relevant for Russia as it is for the United States—to address challenges posed by homegrown, transnationally-inspired Islamist actors and far-right radical groups. Good practices to be shared in select areas might include youth-centered counter/de-radicalization programs, countering extremists’ narratives, degrading extremist abilities to disseminate messages and recruit followers through digital fora/social media.

In terms of learning from each other’s respective CVE strengths, the strongest element in the U.S. CVE approach is its heavy emphasis on community-level policing and engaging local communities and civil society. This approach is hardly applicable to Russia, with its anocratic governance, weakened civil society, and vertically centralized domestic security system. Still, the United States has invaluable experience in community-level policing that Russia should closely analyze and selectively implement. This is true both for the more specific purposes of CVE and in the broader context of major institutional reforms for Russia’s law enforcement sector.

In turn, Russia’s main comparative strength stems from its centuries-long experience in coping with and engaging its core, large native Muslim population (even as Russia also faces the more recent problem of radicalized Muslim migrants). The current American approach to homegrown Islamist radicalization, excessively copying the United Kingdom and EU states, targets populations that are overwhelmingly first and second generation Muslim migrant diasporas. Not all of the European measures are well tailored to the U.S. case, where Muslims are overall more secular and better integrated into society (as with African-American Muslim communities). Ironically, Russia’s experience may actually be of high relevance for the United States on how to avoid “securitizing” large well-integrated domestic Muslim populations (despite heavy security pressures and a harsh stance against fringe Islamist extremists).

The second direction for Russia and the United States to pursue is cooperating actively to solve concrete regional and functional problems of high mutual interest. These range from specific overlapping security matters requiring direct functional/technical contacts and intelligence-sharing to major regional issues of mutual concern, such as with Syria and Afghanistan. Two existing examples of intelligence-sharing include FBI information provided to Russia regarding the 2015 terrorist attack on a Russian charter flight in Egypt and security arrangements for the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

More generally, the United States and Russia are the two powers best poised to keep the global antiterrorism agenda focused on the Iraq-Syria and Afghanistan-Pakistan conflict areas. They could, and should, push for an upgrade of multilateral efforts to advance genuine resolutions to these conflict zones as a long-term global strategy to reduce and prevent terrorism. Both zones involve weak/failed states with intense and heavily transnationalized and regionalized civil wars, and together they account for two thirds of all terrorist activity. Such complex and fragmented regional conflicts require international stakeholders to make hard, context-specific choices. This is especially the case in distinguishing between reconcilable militant actors and irreconcilable transnational violent extremists, and between a radical armed group’s evolution toward inclusion in a national political process and its mere rebranding. Solutions, in and beyond Syria, may not be practical or broadly acceptable internationally without joint problem-solving efforts by the United States and Russia. It is these joint problem-solving efforts that could not only help improve US-Russia bilateral relations, but could also be built upon for re-establishing and upgrading more institutionalized cooperative mechanisms.

Ekaterina Stepanova is Lead Researcher and Head of Peace and Conflict Studies at the Institute of the World Economy & International Relations (IMEMO) and a Professor at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

[PDF]

[1] In 2010, the Afghan Taliban was excluded from the U.S. State Department list of “foreign terrorist organizations.” Russia’s official list of terrorist organizations was first published in July 2006.

[2] As of November 2016, the other seven groups included in both the Russian and U.S. lists were Aum Shinrikyo, al-Qa’ida, Asbat al-Ansar, Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya, Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, Islamic Jihad-Jamaat of Mujahideen/Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb.

[3] See: Ekaterina Stepanova, The “Islamic State” as a Security Problem for Russia: the Nature and Scale of the Threat, PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 393, October 2015,