(PONARS Eurasia Commentary) In a surprise move this past June, Moscow published its first-ever “Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence.” The content core of these fundamental principles looks like excerpts from other Russian documents pertaining to the conditions and “red lines” of nuclear weapons use. The significance of this document is that it accentuates policy aspects that have been under deliberation for quite some time.

One immediate question is whether the idea of using nuclear weapons in a regional conflict as part of an “escalation for de-escalation” strategy still exists in Russia’s military planning.[1] Are the Baltic states, for example, still under such a threat? The Basic Principles may be the most informative in this dimension, despite its own clarity gaps.

Paragraph 4 of the policy (in English) refers to the “prevention of an escalation of military actions and their termination on conditions that are acceptable for the Russian Federation and/or its allies.” The text as-a-whole claims that using nuclear weapons is only for deterrence. Has the “escalation for de-escalation” discussion and strategy changed? Yes, and no: the West and Russia have different interpretations of this central concept.

The West tends to associate the notion with the threat of, say, attacking the Baltic states, but Russia sees it as nuclear-based coercion that prevents NATO from defending these allies. The 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review sees the strategy of “escalation for de-escalation” when or if Moscow “mistakenly assesses that the threat of nuclear escalation or actual first use of nuclear weapons would serve to “de-escalate” a conflict on terms favorable to Russia.” Meanwhile, there are no credible signs that Russia is planning to attack the Baltics, especially with any hint of nuclear weapons, which would open a direct conflict with NATO.

The Basic Principles claim that Russia’s main task is the “protection of national sovereignty and territorial integrity of the State.” This is a rational statement, but there has not been any real threat toward Russia along these points. Russians do have some traditional threat perceptions based on feelings of insecurity within a unique geopolitical interpretation of international affairs. The Russian leadership has always held on to the idea that if it becomes “weaker,” it will be invaded by the West. Looking back, Moscow was invaded two times in history by Western powers: the Poles in 1610 and the French in 1812—the Nazis were stopped a few kilometers from the capital in 1941. But any feelings of insecurity probably strengthened after the breakup of the USSR when Russia lost a major part of its European territories (and therefore strategic depth) and a substantial amount of its military power.

We can also remember the late 1990s when Moscow feared a “Serbian scenario”—when NATO finally moved in to stop Slobodan Milošević from taking over Kosovo. It is not hard to see analogies between Kosovo and Chechnya; the “escalation for de-escalation” clause appeared in the Russian Military Doctrine in 2000, after Moscow destroyed Grozny. The concept has remained in the Russian military posture for twenty years now, as a deterrence fundamental, although the only “borderlands” action we have seen has been Russia’s taking of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 and which it considers its own territory.

The good news about the Basic Principles is that Moscow has written down its defensive intentions—namely toward Europe and NATO—in one document. The bad news is that it has codified its defensive perimeter and “red lines,” which includes Crimea. But as the years pass, Brussels may increasingly be seeing Russia’s annexation of Crimea as a fait accompli.

Among other issues, the nuclear casus belli for Russia is not good news for the West. In particular, now the policy says that only “reliable” information (19-a) is needed about the launch of any ballistic missile toward Russia for there to be a potential response. This undermines the future deployment of U.S. intermediate-range missiles in Europe and missiles connected with the Aegis offshore missile defense system—all of which Russia officially calls offensive infrastructure.

It is worth mentioning that it is not relevant for Moscow whether an adversary’s missiles are nuclear or conventionally tipped, as stated in the text. Among the conditions for the possibility of nuclear weapons use by Russia is the “arrival of reliable data on a launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territory of the Russian Federation and/or its allies.” A Russian strategy based on a launch-on-warning posture only increases the risk of an inadvertent nuclear conflict in Europe.

A related and particularly interesting section in the publication is no. 14, which mentions “offensive weapons” and provides some details:

While implementing nuclear deterrence, the Russian Federation takes into account the deployment by a potential adversary, in the territories of other countries, of offensive weapons (cruise and ballistic missiles, hypersonic aerial vehicles, strike unmanned aerial vehicles), directed energy weapons, missile defence assets, early warning systems, nuclear weapons and/or other weapons of mass destruction that may be used against the Russian Federation and/or its allies.

After the collapse of the INF Treaty, there have been supporters of placing intermediate-range missiles in Ukraine. The aim would be to deploy them at the border with Russia to deter it from further coercive actions in the Donbas region. It is not hard to imagine that the implementation of this scenario from the Western side could turn Kyiv into a defensive object of Russian nuclear deterrence.

Also, the Black Sea region may arise as an area of “allowable” Russian actions. Article 19-c notes that a “red line” would be an attack against critical governmental or military sites or a disruption that “would undermine nuclear forces response actions.” Today, Russia is gradually turning the Black Sea into a Russian basin with the help of its navy and the effective combination of its nuclear and conventional deterrence posture, all of which provide it with anti-access, area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities.

Would an attempt by NATO to deprive Russia of its exclusive A2/AD zone in the Black Sea be counted as a “red line?” Apparently, the Russian Black Sea fleet can be involved in “escalation for de-escalation” tasks—even to counter conventional weapon use, but only when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy (19-d). The policies provide a rather vague formula, which could be utilized in various scenarios (such as the Crimean one).

In sum, it is a welcome development to see Russia’s nuclear deterrence fundamentals amalgamated and published. However, some of the clarifications they provide are counter-balanced by imprecisions that can raise the chances of Russian nuclear involvement in the region.

[1] See: Polina Sinovets, “Escalation for De-Escalation? Hazy Nuclear-Weapon “Red Lines” Generate Russian Advantages,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 605, August 2019.

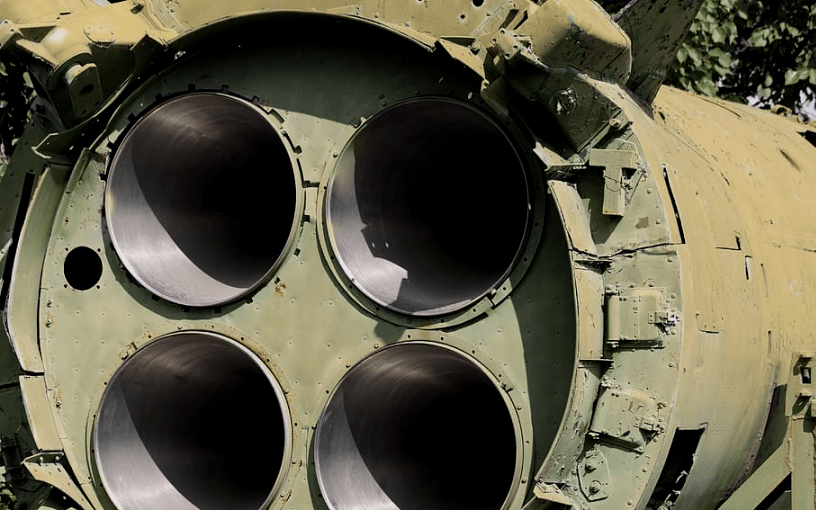

Homepage image credit.