The 2020 constitutional amendments changed Russia’s institutional design significantly. Apart from granting President Vladimir Putin the right to participate in subsequent presidential campaigns, one of the most controversial motions was de jure eliminating municipal independence from regional governments. The constitution’s longstanding Article 12 states that “local self-government shall be recognized and guaranteed in the Russian Federation.” In order to circumvent this protected status, which cannot be amended without adopting a new constitution, the Kremlin put forth a new concept: “the unified system of public power.” This vague idea became legal when two bills were submitted to the parliament in 2021. The president signed the first bill in December 2021, replacing the 1999 law that had served as a framework for center-region relations for more than twenty years. The president now ensures the “coordinated functioning and interaction of the bodies included in the unified system of public power.”

The new provisions are strictly in line with the Kremlin’s policies that Putin has set up over time: the weakening of the autonomy of the regions vis-à-vis the federal center and the strengthening of the authority of governors vis-à-vis regional legislatures. Together, these trends have been intensifying to such an extent that the presidential administration receives effective, sometimes direct, control over regional and municipal affairs. However, regional actors have turned to informal structures to secure their interests if formal mechanisms prove overly restrictive.

Vertical Dimensions of Power

The president’s impact on the formation of the gubernatorial corpus in Russia is indisputable. Even after the return of direct gubernatorial elections in 2012, officials appointed as acting governors before the elections won them in 95 percent of cases. The president also enjoyed the power to dismiss a governor based on a “loss of confidence.” This instrument, however, had its limitations. The formal grounds for a “loss of confidence” included facts of corruption, opening bank accounts in foreign jurisdictions, and the use of foreign financial instruments, such as stocks and bonds, while running for office. The new law relieves the president of the burden of proof that any of these facts took place. As one of the parliamentary deputies noticed during the second reading, this provision makes a governor the most vulnerable employee in Russia, one who can be fired without any justification. At the same time, the president receives more subtle tools to pressure governors, such as “warnings” about signing an order or decree (ukaz) that is counter to federal legislation or “reprimands” for poor performance. These “yellow cards” can easily become red if a governor does not fix a mistake.

At the same time, in a trickling down of authority, the law grants the governors identical powers toward mayors and heads of local administrations. In case of ignoring a governor’s warnings, a mayor, whether elected or appointed by a local “contest committee,” can be removed from office. As is the case with presidential powers, a governor’s discretion is not bound by any clear rules—any loosely defined “improper performance” can be sufficient grounds for pushing a mayor out of office.

The laws also provide the regional procuracy (prokuratura, or “office of the public prosecutor”) with the right to introduce legislative initiatives on top of their already considerable responsibilities and powers. What was seen by many analysts as an invasion of the coercive vertical into regional legislative affairs is, in fact, a consolidation of the status quo. Regional prosecutors have already had this power granted by 82 regions of Russia. The new law simply makes it impossible for regions to revoke this right. The governors also lost their discretion to appoint regional ministers in such crucial policy areas as finance, education, healthcare, and housing. From now on, governors will need to enlist the support of the federal ministries to shape their administrative teams. What had mainly been an informal practice became a strict formal requirement.

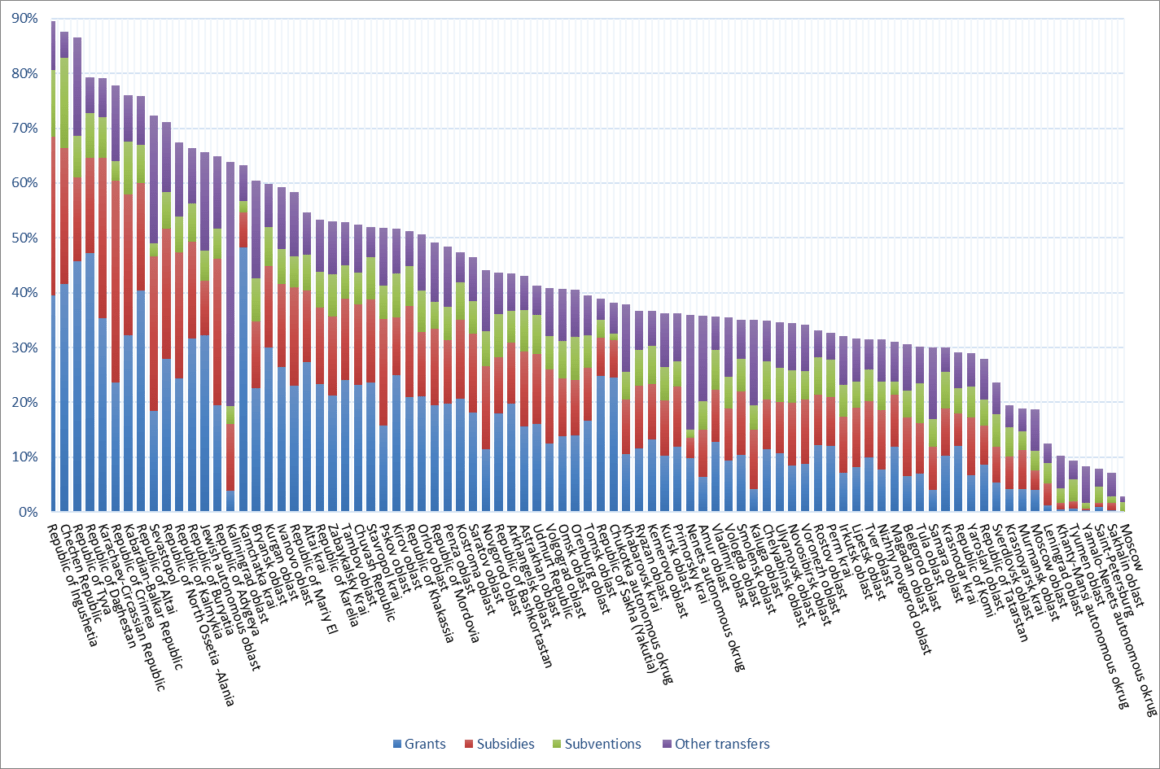

Together, these provisions reduce the already elusive autonomy of regional and local levels of governance in Russia. The two complementary dimensions of such autonomy—budgetary and administrative—have been under attack for the last twenty years. As of 2021, only thirteen regions did not receive federal grants. Generally, the regions’ financial dependence on the broader spectrum of federal funds is immense. Ingushetia and Chechnya are extreme examples of this trend, with 90 percent of their income coming from federal transfers. The median share of inter-budget transfers in regional revenues equals 39.5 percent (see Figure 1). While equalization grants are distributed according to a transparent methodology, all other types of transfers allow for a considerable degree of freedom, which leaves room for informal lobbying and rewarding loyal governors. Moreover, determining the base for the regions’ own income is in the hands of the federal center.

Figure 1. Share of Interbudget Transfers in the Revenues of Russian Regional Budgets, 2020

There are only three regional taxes in Russia: transport tax, gaming tax, and the tax on organizations’ assets. The regions are free to determine rates, procedures, and time limits for paying these taxes, and all collected funds go into regional accounts. Much more lucrative federal taxes, such as personal income tax or excise taxes, can also be transferred to the regions that collected those taxes. Still, their particular share remains at the discretion of the central parliament. Moreover, the corresponding article of the Budget Code changes almost every year, leaving regions uncertain as to what industries and business activities it is rational to support to increase their tax base in the long run. Thus, even the most prosperous regions enjoy rather limited economic autonomy. The situation is similar at more local levels. Only 79 out of 20,023 municipalities did not need their region’s assistance to cover their expenditures in 2020.

The political autonomy of regions and municipalities is substantially restricted, even if the law formally gives them the freedom to form their own public bodies. Gubernatorial elections have replaced the appointment model de jure but not de facto because 95 percent of elected governors since 2012 had already been appointed as acting governors. Also, the Presidential Administration can urge disgraced governors to retire, as was the case with Sergey Levchenko, the Communist Party-supported former governor of Irkutsk. As a last resort, dismissal due to “loss of confidence” can be employed. This approach was used by Putin (and Dmitry Medvedev) thirteen times from 2005 to 2022 to control regional personnel. The autonomy at the local level is not any higher. While more than 1,500 municipalities held direct mayoral elections in 2006, only 250 did in 2018. Since 2016, the dominant model for becoming a local leader has been appointed by the mayor or contest committee. The latter consists of the local parliament’s deputies and the governor’s representatives in equal shares, which de facto gives the regional authorities complete control over the appointment process.

If regions and cities lack practical political and economic autonomy, what is the rationale behind the new “law on public power?” The answer is two-fold. First, the existing centralized system is still capable of producing regional politicians bright enough to enlist public support without dependence on the resources of the Kremlin. Second, attempts to remove governors from power, even appointed ones, can still provoke severe conflicts. For example, Sergei Furgal emerged victorious after a second round of gubernatorial elections in Khabarovsk Krai in 2018, defeating the incumbent governor, Vyacheslav Shport, whom Putin had personally backed. Contrary to the centralization trend, Furgal, with the support of the Khabarovsk regional parliament, brought back direct mayoral elections in the Krai. However, less than two years later, he was arrested on charges of organizing murders. Pending a court ruling, Putin removed the governor from office due to “a loss of confidence.” Furgal’s arrest triggered mass protests in Khabarovsk that lasted several months and became the largest in the city’s history. The protests became a unique example of the unification of regional elites and mass street protests, which is the most hazardous combination for personalized autocratic regimes.

In another example, half a year before Furgal’s arrest, the president relieved the governor of the Chuvash Republic, Mikhail Ignatiev, after he made headlines forcing fire-fighters to physically jump up to grab keys to new fire engines during an official ceremony in Cheboksary. Unlike Furgal’s case, Ignatiev’s dismissal did not provoke a public outcry but revealed a legal gap in the institutional term: “loss of confidence.” The presidential decree on the matter did not contain any grounds for dismissal, which gave Ignatiev cause to file a lawsuit against Putin in Russia’s Supreme Court. Having no chance of success, Ignatiev issued a symbolic challenge to the president by putting him in the position of defendant. This move was a clear violation of the informal code of relations within the Russian elite and an obvious threat to the symbolic superiority over other political figures that lies at the heart of Putin’s public image.

The redefined powers of the president toward governors seek a balance between ultimate control over regional elites and reduced risks of conflicts. No one can claim that a dismissal is unlawful if no law defines its terms and conditions. Furthermore, it removes the need for drastic steps such as opening a criminal case to remove a governor. The administrative system of “yellow cards” transfers the decision to dismiss a governor from the political to the bureaucratic realm, making it less shocking for the public yet opening room for informal negotiations with rebellious regional elites. Regional administrations may use the same bureaucratic mechanisms to remove local leaders that are fairly independent of subnational authorities and hence loosely embedded into the “power vertical.” Such leaders can still emerge even within highly restrictive institutional settings, as examples of the former mayor of Yakutsk, Sardana Avksentyeva, or the former head of Yekaterinburg, Yevgeny Roizman show.

Horizontal Dimensions of Power

The horizontal separation of powers has undergone less significant change but followed a long-term trend of weakening the autonomy of regional assemblies. The president and governors retained their right to warn and dissolve regional parliaments. At the same time, the latter lost their power in defining the structure of regional governments, which the new law handed over to the governor exclusively. What caused the most pronounced indignation of the Communist Party faction in the parliament was the elimination of the minimal threshold for party-list proportional representation in regional legislative elections, which constituted 25 percent according to the previous law. Furthermore, regional deputies were equated with civil servants in being barred from running a business, having foreign bank accounts, and using international financial tools while in office.

Shrinking parliamentary autonomy and the change in the electoral rules can also be seen as a reaction to recent political developments. With all its administrative advantages, the ruling United Russia party could not win recent legislative elections in Irkutsk, Ulyanovsk, or Khakassia. The electoral loss of United Russia was incredibly profound in Khabarovsk Krai, where it received just 12 percent of the vote, finishing third on the party list, which translated into just two seats in the regional assembly. The declining popularity of United Russia makes the first-past-the-post system preferable for the ruling party in all upcoming elections yet gives the remaining opposition more chances for a consolidated protest vote.

Conclusion

Establishing Russia’s “unified system of public power” appears to be driven by reactive rather than proactive considerations. The resulting centralization, however, comes at a cost. If regional actors cannot satisfy their interests through formal mechanisms, they will find informal ones. The rising price for direct participation of regional business groups in legislative affairs creates incentives for informal lobbying behind the scenes and the enlisting of proxy deputies. Furthermore, the growing role of the federal bureaucracy creates too many focal points for local elites in shaping their regional governments, making negotiation processes complicated and uncoordinated. Altogether, the posts of governors, ministers, and deputies have been becoming ever-more associated with responding to the federal center, prompting them to lose their attractiveness to local elite groups. All this leads to a disassociation between formal, regional centers of power and local, informal groupings, which can result in the Kremlin either tightening its fist activities or losing its grip on regional politics, which is the opposite of what the “unified system of public power” intends to achieve.

Kirill Melnikov is a Researcher at the Institute of Philosophy and Law, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Yekaterinburg, Russia, and a Visiting Scholar at George Washington University.