(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) The pandemic presented Russia’s long-serving, authoritarian government with a rare and ongoing opportunity to advance its interests vis-à-vis the West. Chaotic responses nearby in the EU and beyond to the extraordinary epidemiological emergency created an opening that the Kremlin endeavored to exploit through assistance and a quickly developed vaccine: Sputnik-V. In a throwback to Soviet-era global competitiveness, the Russian media have been portraying Moscow’s anti-coronavirus actions as magnanimous while pointing to the lack of solidarity in the West—all while it is still under multiple rounds of sanctions. The likely calculus is to elevate Russia’s status on the world stage while fostering divisions among adversaries where possible. However, delays and several controversies have revealed the haphazard and improvised character of President Vladimir Putin’s anti-COVID-19 charm offensive. On a positive note, Sputnik-V is now being administered and may prove to be sound, but misinformation and mismanagement continue to surround it.

Working the Contrasts

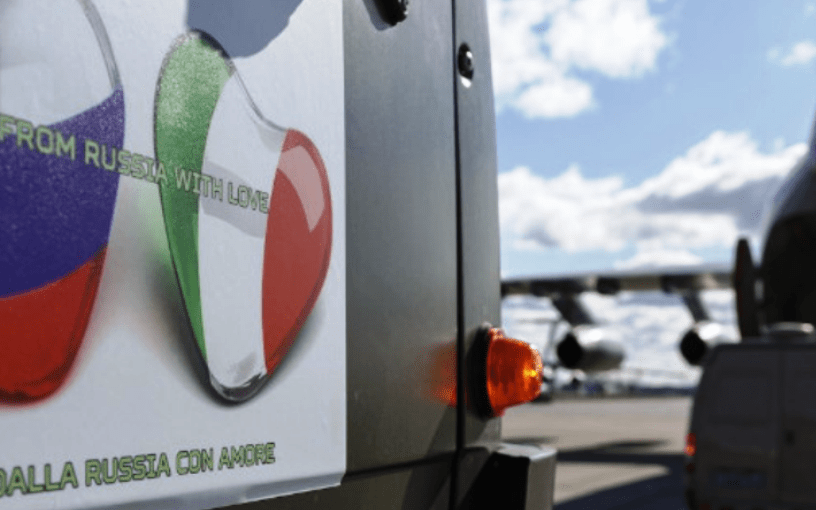

During the initial phase of the outbreak in April-May 2020, the Russian government delivered COVID-19-related aid to 46 countries around the world. In Europe, Russia’s aid recipients were Italy, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In March, several planeloads of medical equipment were sent “from Russia with love” to the badly virus-battered Italy. These actions were loudly trumpeted in the Russian state-controlled media as an expression of Russia’s magnanimity and generosity. However, later, the plan spectacularly backfired when the Italian media reported that Russia’s 104-man-strong team of medics included operatives from Russia’s military intelligence service (GRU) and that at least 80 percent of the supplies were useless. Even more embarrassing was the report in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica on April 12 that the Italians were offered 200 Euros for recording videos thanking the Russian authorities for their assistance.

A similar fiasco awaited Russia’s dispatch of medical equipment to the United States when it turned out that the Aventa-M ventilators were blamed for at least two fires at Russian hospitals in Moscow and St. Petersburg that left six COVID-19 patients dead, leading the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to ban their use. Subsequently, Russian medical staff, who had worked with the equipment, admitted to The Moscow Times that they were faulty. Nevertheless, in a gesture of goodwill, Washington reciprocated by sending $5.6 million worth of medical equipment, including 200 ventilators, to Russia.

The Kremlin was also not successful in its attempts to promote a Russian version of a UN General Assembly (UNGA) declaration on COVID-19, which underneath was aimed at lifting post-Crimea sanctions. Also, Russian efforts fell short when Moscow failed to promptly deliver medical aid to Serbia, a close Russian friend, as was done by China when it sent aircraft to Belgrade and the EU, which promised funds.

Sputnik-V and Russia’s Simple-Minded Vaccine Race

The Russian government’s fast-track approach to vaccine development clearly reflects its desire to be at the forefront of the global fight against COVID-19, which will, in the Kremlin’s calculus, place Russia as a great power. In his pre-recorded address to the UN General Assembly in September 2020, Putin boasted that Russia was the first country to register an anti-COVID-19 vaccine, Sputnik-V, and was offering to share it with the world. Russia’s Ministry of Health released the first batch of vaccines for domestic distribution on September 8, with nationwide vaccination to commence in October.

Meanwhile, the scientific data undergirding the Russian vaccine were provided to the Western scientific community in early September amid questions about its integrity—as reflected in an open letter to the principal inventor of the Russian vaccine from 19 scientists from Italy, France, Germany, the United States, and Japan. Notwithstanding doubts about the efficacy of the Russian vaccine in the Western scientific community, the Russian government was very busy promoting it. This was reflected in preliminary agreements to supply 1.2 billion doses of Sputnik-V to ten countries in Asia, South America, and the Middle East, including Brazil, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and India. Russian diplomats have been actively promoting Sputnik-V in Egypt. As of December 31, more than 50 countries placed orders for a total of 1.2 billion doses of Sputnik-V, according to the state-owned Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), which oversees its production and distribution.

The beginning of 2021 brought both opportunities and setbacks for Russia in its pharmaceutical competition with the West. Countries had to make procurement decisions. In early January, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a close ally of Putin, chose to purchase China’s vaccine instead of Russia’s, saying that Sputnik-V had insufficient production and capacity. In November, The Bell reported that none of the four major enterprises—R-Pharm, BinnoPharm, Generium, and Biokad—tasked with the production of Sputnik-V were ready for its mass production.

Amid burgeoning online memes,[1] Algeria and Bolivia joined the Sputnik-V queue, as well as India (100 million doses), Brazil (50 million), Uzbekistan (35 million), Mexico (32 million), and Nepal (25 million). Although the vaccine’s efficacy has not been conclusively proven, it has a price-point advantage; it costs roughly $10 per dose, which is less than its main competitors, Pfizer ($20) and Moderna ($33).

On December 29, 2020, Argentina became the third country after Russia and Belarus to authorize vaccinations using Sputnik-V. Only one percent of those vaccinated experienced side effects, according to the Argentinean media. On January 1, India’s state regulator approved two vaccines, AstraZeneca and COVAXIN, ahead of Sputnik-V. Given the sheer size of India’s population, the vaccination campaign there will probably be the largest in the world, and the authorities put forth an ambitious objective of vaccinating 300 million people in 6-8 months. Serbia commenced mass vaccination with Sputnik-V on January 5, but it runs in parallel with the one that started earlier using the Pfizer vaccine.

Doubts at Home and Abroad

Meanwhile, the epidemiological situation within Russia sharply deteriorated throughout 2020, leading the government to finally admit that COVID-19 was responsible for 81 percent of the increase in the annual overall mortality rate in Russia. This implied that more than 186,000 people died from COVID-19 in Russia in 2020, making it the third worst hit by the pandemic after the United States and Brazil. What makes the situation worse is that there is a very high degree of public skepticism toward the vaccine. According to a global survey of public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination conducted by Ipsos in mid-December 2020, only 43 percent of respondents in Russia expressed the willingness to get vaccinated, which was the second-lowest after France (40 percent) and far behind the United States (69 percent), Canada (71 percent), UK (77 percent), and China (80 percent).

As of January 22, 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) had not issued the certification necessary to launch the production and/or distribution of the Russian vaccine in the EU. In early winter, on December 9, EMA’s Executive Director Emer Cooke stated that the agency did not receive a request for authorization from either Russia or China. But on January 5, Putin discussed the possibility of the joint production of Sputnik-V with Germany with Chancellor Angela Merkel. However, a day later, the German government’s press spokesperson Ulrike Demmer clarified that the production of Sputnik-V in Germany would only be possible with EMA’s approval. The lack of EMA authorization did not seem to deter Moscow from actively seeking to market Sputnik-V in Europe. Russia’s RDIF applied to EMA for registration of Sputnik-V in the EU on January 20, but apparently, it is still “not undergoing a rolling review” by EMA. Hungary, which made headlines by declining the Russian vaccine at first, became the first EU country to agree to buy the Russian vaccine.

Questions have been raised not only about the Russian government’s ability to organize a mass vaccination program domestically but also about its commitments delivering Sputnik-V to other countries in accordance with contractual obligations. As of January 5, about a month after mass vaccinations in Russia commenced, only about one million were vaccinated, according to Alexander Gintsburg, director of the Gamaleya research center, a developer of the Russian vaccine. About one week later, the press reported that one-and-a-half million Russians had received the Sputnik-V vaccine, but some experts suggest that the vaccination numbers are significantly lower.

Conclusion

The Russian leadership felt that the global rollout of Sputnik-V would be a competitive, triumphant creation. In the aftermath of Alexei Navalny’s poisoning, the Russian government found itself in such a dire predicament in terms of reputational damage that its vaccine was seen as a viable, if risky, strategy to change the narrative, “beat the West,” and improve its position on the world stage. In this sense, Moscow had little to lose because even if Sputnik-V turned out to be ineffective in comparison with Western vaccines, the consequences would be limited to canceling contracts and arbitration at most. If the Russian vaccine proved to be effective, Putin’s regime would share the news widely while highlighting transatlantic deficiencies and divisions. In the end, as multiple vaccines including Russia’s reach communities around the world, the results of Putin’s COVID-19 charm offensive will be transient.

Alexandra Yatsyk is a Coordinator of the Baltic-Black Sea Region Project at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

[PDF][1] See, for example, artist Andrzej Rysuje’s image of Sputnik-V soaring over other vaccines on Facebook.

Homepage image credit.