Not only do the overwhelming majority of Ukrainians remain resolute in their commitment to driving Russia out of Ukraine’s internationally recognized territory, but this commitment is strongly fused with a determination to be a healthy, thriving democracy and to honor and avenge their devastating shared losses and sacrifices. These are two of the main findings from two new surveys, in addition to focus groups, conducted across Ukraine in June-September 2023.

The first survey is a longitudinal study of 329 respondents, broadly representative of Ukraine’s population in territories under Kyiv’s control, who were first interviewed as part of the Ukraine National Academy of Sciences Institute of Sociology’s larger annual monitoring survey in November 2021. They have since been reinterviewed in June-July 2022 and in the second half of June 2023. The second is a survey of 869 new respondents polled in late June 2023. Our four focus groups, conducted in mid-September 2023, each had eight participants and represented Ukraine’s macro-regions: Center (Kyiv and Kyiv province); West (Lviv and Ivano-Frankivs’k); East (Kharkiv and Donetsk); and South (Odesa and Mykolaiv).

Our 2022 and 2023 surveys reflect changes in territorial control and population movements in Ukraine during wartime, making them valuable for assessing the state of public opinion in territories governed by Kyiv, but not in territories under Russian occupation, in the contested settlements along the line of high-intensity fighting, or among Ukrainians who have fled to Russia or other countries. Our research design, data, and methods of analysis, however, mitigate the effects of changes in the regional composition of the sample and some other problems typical of wartime polling.[1]

Mounting War Toll

Ukraine is in a long, brutal war. Our survey data show deep, widespread, and growing personal loss and trauma (see Figure 1). The number of Ukrainians reporting family members and friends killed or wounded; having lost jobs, homes or other property; or having to flee the war zone rose from 20 percent to 80 percent between November 2021 and June 2023. Particularly notable in the last year is the increase in the number of people reporting the death or injury of their nearest and dearest (see Figure 1). All year-on-year increases are statistically significant, meaning they are unlikely to have occurred due to chance or individual inconsistencies.

Figure 1. War Loss in Ukraine Panel Survey (2021-2023, N=329)

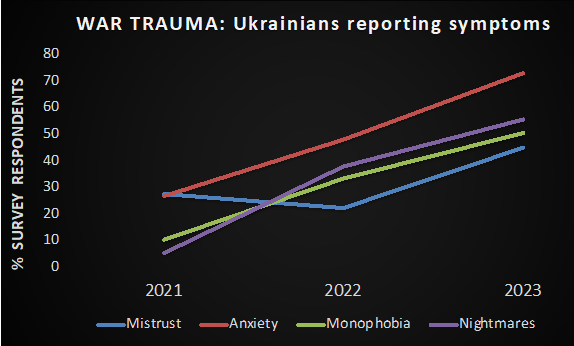

We also observe a stunning rise in the number of Ukrainians reporting typical symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), particularly anxiety, war-related nightmares, and fear of being alone (monophobia). Alarmingly, all these symptoms have increased with each successive survey wave. The tendency to mistrust everyone—which declined in the first four months after the mass invasion, possibly reflecting unprecedented rallying and solidarity—had also increased considerably by June 2023 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. War Trauma in Ukraine Panel Survey (2021-2023, N=329)

Victory Commitment and Meaning

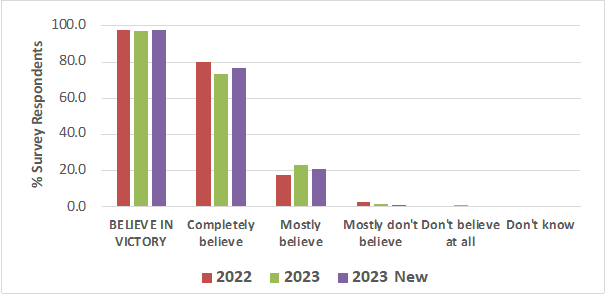

Despite mounting loss and trauma, Ukrainians overwhelmingly continue to believe in victory over Russia and remain determined to restore Ukraine’s full territorial integrity. As Figure 3 shows, about 97 percent of people in our tracking poll, as well as in the new control poll of June 2023, said they believed in victory. The 6.5 percentage-point shift in the tracking poll from “completely believe” to “mostly believe” between 2022 and 2023 is not statistically significant and is less pronounced (at about two percent) in the June 2023 survey (see Figure 3).

Based on the larger June 2023 poll (N=869), belief in victory was practically uniform across Ukraine’s four macro-regions, with near-identical figures in the West, South, and East and slightly higher ones (about 1.25 percentage points on average) in the Center.

Figure 3. Ukrainians Express Overwhelming Faith in Victory

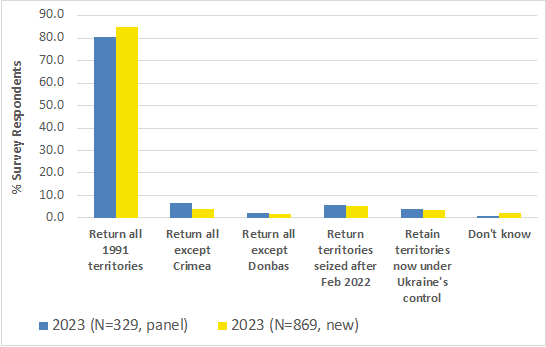

Ukrainians are determined to restore their country’s sovereignty within the internationally recognized 1991 borders. About 80 percent of respondents to both the tracking poll and the new 2023 poll expressed that view. A further 16 percent want a return of at least some of the territories that have been occupied by Russia since 2014 and 2022. Only around four percent of survey participants would be satisfied with keeping solely the territory Ukraine currently controls (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. To Ukrainians, Victory Means Retaking All Occupied Territories

These findings confirm longer-term trends identified in other surveys across Ukraine, as well as the remarkable uniformity of views across Ukraine’s macro-regions: in our larger 2023 poll (N=869), the share of respondents defining victory as the return of all occupied territories was 84 percent in the West, 86 percent in the Center, 87 percent in the South, and 82 percent in the East.

Victory-Freedom Complex

The increasing toll of the war has not dampened Ukrainians’ support for political freedom. In fact, it appears that this suffering has engendered a clearer understanding of the importance of continued fighting by building a sense of shared sacrifice and raising the value of political freedom.

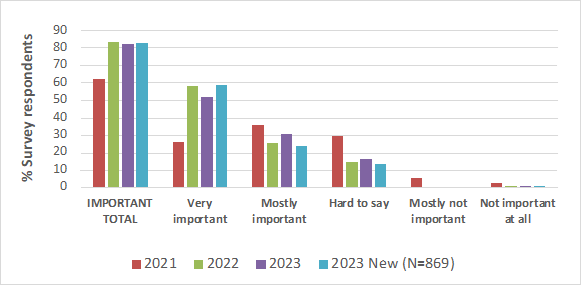

Over 80 percent of respondents to our 2023 polls—about the same share as in 2022—said democracy was very or mostly important to them personally. An shift of about six percentage points from “very important” to “mostly important” in our tracking poll (N=329) was not statistically significant, and our new poll of 869 respondents in June 2023 generated results nearly identical to those we saw in the tracking poll a year ago (see Figure 5). The findings were virtually the same when respondents were asked whether free speech was important to them.

Figure 5. Democracy Remains Important to Overwhelming Majority of Ukrainians

A more detailed analysis controlling for age, gender, language use, income, and region indicates that support for freedom has solidified in the crucible of war:

- In the 2023 wave of our tracking poll, Ukrainians who had suffered losses in the war continued to value democracy about as strongly as they did in 2022, while those who reported no war losses valued democracy somewhat less than before (on average about six percent lower, a statistically significant difference). We found the same result for 2023 with our new poll of 869 respondents. (In 2022, support for democracy was about the same regardless of loss, probably reflecting the massive rallying against Russian invasion in the first months of the full-scale war.)

- In both the 2022 and 2023 waves of our tracking poll, as well as in the new June 2023 poll, Ukrainians who believed in Ukraine’s eventual victory in the war were about 25 percent more likely to see democracy as important than those who did not believe in victory. Experiencing losses in the war had no significant effect on belief in victory.

Our longitudinal statistical analysis of the tracking poll data, which factored in both differences among respondents and differences among the same respondents over time, further found that:

- The onset of the war in 2022 remained a major driver of support for democracy in 2023.

- The war mobilized national identity in support of democracy as a system of government and of free speech; in 2023, Ukrainian language use emerges as a key correlate of democracy, the other main sociodemographic factors and war effects being equal; and the design of statistical tests indicates that most of this relationship is due not to preference falsification, but to a genuine desire to turn to Ukrainian symbols and identity in the face of Russian invasion.

- Not only does democratic resilience come at a massive human cost, but the challenges abound. Suggesting that the current war is also a war of ideas and media influence, in tracking poll respondents who in November 2021 listed Russia as one of their main news sources tended to be less supportive of democracy as a political system (although they still supported free speech about as much as others).

On aggregate, these findings point to the emergence of a victory-freedom complex in Ukrainian society that is driving sustained resilience in the face of the rising toll of the Russian invasion.

The reason for this resilience emerged clearly from our focus group discussions: any failure to drive Russia out of all occupied territories is simply unthinkable. It is incomprehensible given the tremendous sacrifices Ukraine has borne to fight off Russia’s efforts to strip Ukrainians of their freedoms and national identity.

This insight comes from focus group participants’ reaction to the question: “To what extent do you believe public support for Zelensky will depend on the outcome of the war? What if the war does not end the way we expect it to end?” Of the 24 participants who engaged on the question, only nine gave specific answers. Most others expressed disbelief in the very premise of the question, implying that to them the war will not end if Ukraine does not reclaim all occupied territories. The following statements summarize the prevailing mood:

- “And for what did people die, then? For what did they lose their arms, legs, homes, property? For what? For what did a mother lose her son?” Natalya, 47, Lviv (displaced, originally from Mar’inka, Donetsk oblast).

- “Why, then, did our men die? For what have our boys been killed since 2014? What are the Allies of Glory memorials for? What has everything been for?” Angela, 46, Mykolaiv.

- “Zelensky then will no longer be Zelensky. … I will then demand that he takes up arms himself and fights to return Crimea, Donbas, and Luhansk.” Dmytro, 18, Mykolaiv.

- “Our president said that if we don’t return our territories within 1991 borders, then it will not be victory, it will be capitulation. So the war will go on till we reach our borders. And that’s it.” Lyudmila, 50, Kyiv.

- “One person cannot win a war. And we all, the whole nation, are trying, helping every way we can. He, as president, does the right thing. So far, the right thing. Victory will be ours.” Vyachaslav, 70, Mykolaiv.

Global Implications

Our surveys and focus groups clearly show how hard it would be for Ukrainians to accept any ceasefire or peace agreement that would entail the loss of territory to Russia. They also imply that if the United States and its allies reduce support for Ukraine, Ukrainians will continue to fight. Given the massive increases in Russian military spending that are projected for next year, it is clear Moscow will push on. Evidently, therefore, the realistic choice is not between continuing the war and trading peace for land (as many in the Biden administration may hope), but a war in which Ukraine receives more advanced and sizable military aid faster, increasing its odds of pushing Russia out of the occupied territories within a year or so, or a grinding war with diminishing Western assistance and possibly renewed Russian advances, which may last for years and spawn unfathomable global consequences—from empowering China, North Korea, and Iran and its Middle East proxies, including Hamas, to challenge the US and its allies more boldly, to the renewal of civil war in the former Yugoslavia, to greater instability in the Sahel coup-belt, to greater Russian sway over Latin America.

Mikhail Alexseev is a Professor of Political Science at San Diego State University.

Serhii Dembitskyi is Deputy Director of the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

[1] In our tracking poll, the initial sample of 1,800 was obtained before the war through in-person selection protocols. Shifts on basic demographics in follow-up telephone surveys indicate that discrepancies on basic demographic characteristics (age and gender) were within the margin of sampling error. The largest changes in the follow-up samples were the decline in the share of respondents residing at the time of the survey in the Donbas (from 6.7 percent in 2021 to about 1.2 percent in 2022 and 2023) and in the South (from 16.3 percent in 2021). Notably, we had no respondents residing in the Luhansk Oblast in 2022 and 2023 or in Kherson Oblast in 2023 (and only 3 in 2022). The total maximum effect of these shifts in regional composition on any given question is about 10 percent—assuming, improbably, that these changes would have a uniformly opposite effect. Based on typical results, however, the effects are most likely to be less than 5 percent. Partly mitigating against this attrition was our ability to retain much the same proportions of respondents by region based on their 2021 residence (the percentages of these respondents for 2021 and 2023 are 23 v. 20.4 for the East; 16.3 v. 18.8 for the South; and 6.7 v. 6.1 for the Donbas). In our larger (N=869) new sample in 2023, we had a slightly larger share of respondents who resided in the Donbas (1.8 percent) and some respondents (N=11) in Kherson. Our use of mixed linear models for statistical analysis also controlled for within-subject shifts on language and income.