Image credit/license

Despite the unprecedented Western sanctions imposed over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Russian economic and political system has so far demonstrated remarkable resilience, effectively coping with the crisis and successfully adapting to multiple challenges. A distinctive feature of this crisis is that, since its scale, duration, and outcome are far from clear, it requires the Russian leadership to implement long-term solutions to transition the national economy onto a war footing. President Vladimir Putin has called this “integrating [the war effort] into the economy.” While Russian gross domestic product officially declined 1.2% in 2022, it bounced back with 3.6% growth in 2023, mostly driven by a ramp-up in the defense sector and related industries.

Maintaining this resilience will ultimately determine the survival of the current political regime in Russia and thus represents a critical task for Putin. Generally, we define authoritarian resilience as the capacity of a regime to persist in its current form by effectively coping with various disruptions, adapting to emerging and future challenges, and eventually transforming in ways that maintain its functioning while keeping the current authoritarian incumbent in office. While resilience (both democratic and authoritarian) is a multidimensional phenomenon that cannot be fully explained by a single factor, we argue that in territorially vast and diverse countries, “territorial resilience” is one of the main pillars for regime stability. In the case of Russia today, a lack of territorial resilience could undermine the Kremlin’s ability to cope with the crisis triggered by the invasion of Ukraine.

‘Territorial Resilience’ and the Kremlin’s New Cadre Strategy for the War

Territorial resilience can be assessed along two main dimensions. The first is the ability of the center to maintain control over the entire territory of a country. It is of principal importance that all regions demonstrate full loyalty to the national center, supporting all its initiatives and taking responsibility and blame for any failures of the center’s policies. The second is the ability of regional elites to effectively respond to challenges spawned by crises and deliver effective performance. These dimensions are deeply interconnected, and both, from the perspective of the Russian leadership, depend on the proper selection of personnel at the national and regional executive levels.

Moscow needs new leaders, and so do the regions: Cadres appointed before the war are more likely to struggle to carry out the new tasks required to militarize the national economy. In other words, the Kremlin must find federal- and regional-level cadres who will prove resilient to previously unseen challenges in the context of the Ukraine war. Importantly, they should be capable of effectively working together.

We analyze the personnel shifts that have occurred between the federal and regional levels since the start of the war. We argue that the previous cadre strategy continued to operate on inertia from the beginning of the war in February 2022 until early 2024, remaining largely unchanged from the prewar period as the Kremlin initially bided its time. Following the 2024 presidential election, however, the shift to a new strategy began because: (1) it had become clear that the war and sanctions would not end soon, and that the war effort needed to be “integrated into the economy;” and (2) a window of opportunity opened after the March 2024 presidential election, when a new government could be formed. This resulted in both “vertical” and “horizontal” reshuffling of federal officials and regional governors. In particular, several surprising changes were made at the federal level in May 2024, including four governors being appointed to head government ministries (the largest number called up in modern Russia’s history). These “promotions” to Moscow and new gubernatorial appointments have established the framework of the Kremlin’s new personnel strategy, geared for adaptation to the new reality.

The ‘Coping Period’ of 2022-2024: Maintaining the Status Quo in Personnel Policy

During what we call the “coping period,” from the start of the war until early 2024, the Kremlin generally opted to keep federal officials and governors in their positions and maintain the status quo, with the personnel changes that did occur being rather routine. In May 2022, Putin accepted the resignations of governors in five regions and appointed acting ones. Two others resigned in 2023. Of the total seven governors who left office in 2022-2023 (see Table 1), four were finishing their first term, while Sergei Zhvachkin of Tomsk and Valery Radaev of Saratov both resigned in May 2022 as their second term was ending. The governor of Vologda, Oleg Kuvshinnikov, left office in October 2023 while serving his third term. Six of the seven received “honorable” positions at the federal level. Saratov’s Radaev, Ryazan’s Lyubimov, Krasnoyarsk’s Uss, and Vologda’s Kuvshinnikov became senators in the Federation Council, the upper chamber of the Russian parliament. Tomsk’s Zhvachkin went to Gazprom, while Kirov’s Vasilyev was appointed as a deputy head of the Federal State Statistics Service. This smooth transition from regional- to federal-level roles suggests a lack of friction in relations between the different levels of power.

Table 1. Turnover of governors in 2022-2023

Their successors, appointed by Putin as acting governors, came from diverse backgrounds. Only one, Roman Busargin in Saratov, was a “local,” having served as vice governor prior to his appointment. Three other appointees—Alexander Sokolov in Kirov, Pavel Malkov in Ryazan, and Yuri Zaitsev in Mari El—were complete “outsiders,” with no prior connection to these regions. Additionally, there was a group of so-called “returnees”: Vladimir Mazur in Tomsk, Georgy Filimonov in Vologda, and Mikhail Kotyukov in Krasnoyarsk. They had some connection to these regions but had subsequently lived and worked elsewhere. Thus, the Presidential Administration largely adhered to its prewar approach of appointing governors to regions where they had either weak or no ties among the regional elites.

The Kremlin Shifts Cadre Policy to Adapt to Long War and Confrontation with West

Starting in early 2024, the Kremlin’s cadre strategy started to shift, marked by vertical and horizontal reshuffling of federal officials and governors. The presidential election in March 2024 and the subsequent formation of a new government created a window of opportunity for major personnel changes to address new challenges and tasks. The first step entailed replacing long-time Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu with economist Andrei Belousov, who had been serving as a first deputy prime minister. Given Belousov’s economic expertise, combined with his experience in various industrial sectors (including the defense industry), he was seen by the Kremlin as well-suited to manage the military’s significant budgetary demands.

To judge by his previous work, Belousov’s core belief is that the state is the driver of the economy and innovation, a perspective consistent with Putin’s vision of state sovereignty. The main task of Belousov is far more complex than what was asked of Shoigu as the minister of defense: He is expected to “integrate [the war effort] into the economy,” i.e., ensure that the Russian economy, despite Western sanctions, can continue to sustain its military machine while enhancing its competitiveness. Belousov’s appointment clearly signals that the Kremlin is preparing for a long and costly war in Ukraine, that current and future wars will demand ever more export of weapons from Russia. In addition, the Russian leadership seems to be operating on the assumption that global conflicts are set to increase, which will spur demand for Russian arms exports.

The second step of the Kremlin’s new cadre strategy involved calling up the most promising governors to federal positions in Moscow. There were five such governors, four of whom became ministers. Mikhail Degtyarev, the governor of Khabarovsk, was named minister of sports, while Anton Alikhanov from Kaliningrad was appointed minister of industry and trade, becoming the youngest member of the government. Note that Alikhanov had served in 2013-2015 as a deputy director and then the director for state regulation of foreign trade at the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Roman Starovoyt of Kursk was tapped to be minister of transport. Finally, Sergei Tsivilev, who headed Kemerovo Region, was selected as minister of energy. The fifth governor brought to Moscow, Alexei Dyumin of Tula, was made Putin’s aide and secretary of the State Council.

During a meeting with the new government, Putin stated that he expected the new ministers, especially the four former governors, to “prove themselves” and expressed the hope that “They will use their skills and the experience they have gained in the Russian regions to their fullest advantage when addressing the tasks they will face in the federal government.” It is the promotion of Dyumin, however, that is arguably the most “eye-catching.” Putin’s bodyguard during his first and second terms, he is considered one of the president’s closest allies. He is now tasked with overseeing the defense industry, the State Council (an advisory body to the president), and sports.

As the dust was settling from Putin’s post-inauguration cabinet reshuffle, the Presidential Administration issued a new set of guidelines for its propagandists. Documents obtained by Meduza show that Russian state-controlled and pro-Kremlin media outlets were instructed to focus their coverage on the former regional governors who were promoted to ministerial positions, highlighting that they had earned these promotions through “effective work” while emphasizing their unique capabilities. For instance, Tsivilev was to be presented as having “proved himself” by “managing a complex region with its own specifications.” Starovoyt is “battle-tested,” since Kursk Region is “on the front line” and regularly shelled. Finally, Degtyarev “led a complex region” and “gained voter support.”

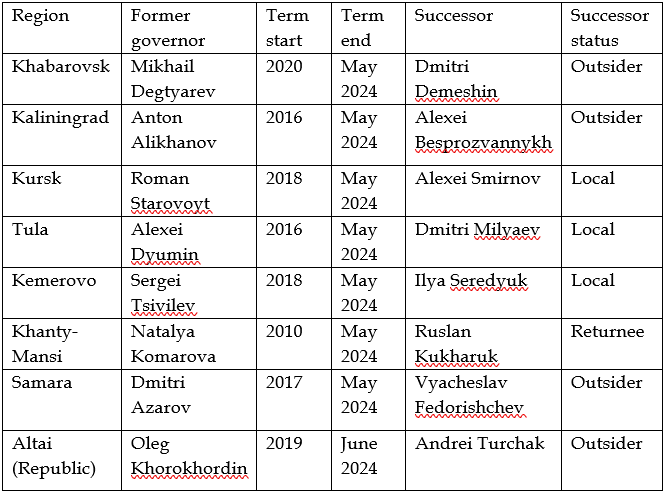

At the end of May, two other governors, Natalya Komarova of Khanty-Mansi and Dmitri Azarov of Samara, resigned. Komarova, who had headed the region since 2010 and was reelected for a third term in 2020, could have stayed in office until 2025. In September, she was appointed to represent Khanty-Mansi in the Federation Council. Meanwhile, Azarov stepped down after one term, heading to the state-owned defense conglomerate Rostec to serve as an advisor to CEO Sergei Chemezov. Given that Rostec supplies nearly 80% of the arms for the war in Ukraine, Azarov’s experience in the defense-heavy region of Samara is expected to prove valuable at Rostec. In 2022, enterprises fulfilling state defense orders in Samara managed to ramp up their production by 21%. Finally, Oleg Khorokhordin of the Altai Republic resigned in June (“in connection with the transition to a new [unnamed] workplace”). As shown in Table 2, eight governors were replaced in May-June 2024.

Table 2. Turnover of governors since 2024

Putin appointed three locals, four outsiders, and one returnee as acting heads of these regions. The locals included Alexei Smirnov in Kursk, Dmitri Milyaev in Tula, and Ilya Seredyuk in Kemerovo, all of whom had been serving as first deputy governors before their appointments. The outsiders were Dmitri Demeshin in Khabarovsk, Alexei Besprozvannykh in Kaliningrad, Vyacheslav Fedorishchev in Samara, and Andrei Turchak in the Altai Republic. The latter appointment was particularly surprising: Turchak previously held two high-level positions at the federal level (in the leadership of the United Russia party and the Federation Council), which made this role appear to be a demotion. Finally, Ruslan Kukharuk in Khanty-Mansi is a returnee. Born and educated in the region, he had moved to neighboring Tyumen, where he served as city mayor most recently.

The Samara and Tula appointments reflect the particular importance of these regions in the current circumstances, since together they account for a substantial share of the defense industry. With Dyumin promoted to Moscow, his associate Milyaev stayed behind in Tula, while Fyodorishchev, another Tula deputy governor under Dyumin, was tapped to replace Azarov in Samara. Fyodorishchev worked for over eight years in Dyumin’s team in Tula and refers to him as “my commander.” Tula and Samara will continue to be overseen by Dyumin in his new role in Moscow. For their part, Milyaev and Fyodorishchev possess specific skills and insights related to the defense industry, with the Kremlin deeming them capable of addressing the new challenges stemming from the militarization of the national economy.

Kremlin Again Opts to Tackle New Challenges with Personnel Changes, Not Reforms

In the first two years of the Ukraine war, the Kremlin’s strategy remained unchanged. However, the recent partial reshuffling of elites at both the federal and regional levels indicates that the leadership anticipates a protracted war and confrontation with the West. As defense minister, Belousov has been asked to solve fundamentally different problems than his predecessor dealt with. Meanwhile, the governors who have been promoted to federal roles are expected to act more energetically and coherently to “integrate [the war effort] into the national economy.”

The Russian political regime is responding to the war-related crisis not with institutional reforms, but with personnel changes, with the goal of finding and correctly placing the “right people.” The new cadre strategy is just beginning to be implemented, and more moves may follow. At the behest of the Presidential Administration, it is being supported by pro-Kremlin media to highlight the “success” of Putin’s personnel policy and his ability to make “unerring and thoughtful” choices. This approach is consistent with how the regime has historically addressed other issues, such as corruption. Its limitations are well known.

Irina Busygina is a research fellow at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University.

Image credit/license