The detention of several pregnant Russian women at the Buenos Aires airport in March 2023 highlighted the new wave of Russian migration to Argentina. Argentine migration authorities accused these women of being “false tourists” whose real goal was giving birth in Argentina to ensure their babies would gain Argentine citizenship. This episode has fueled debates about the presence of Russians in Argentina, prompting police investigations against migration brokers and the introduction of new requirements for “digital nomad” residence permits.

Drawing on longitudinal survey data from the OutRush project, official migration statistics from across the region, and in-depth interviews and sociological observation of Russian immigrants to Brazil, we explore the emerging trends of war-induced Russian migration to Latin America. Russians have visa-free access to the region, which already appeals to families seeking legal residency via jus soli citizenship for their children and family reunification policies. The region may slowly attract more Russian emigrants as they face legal insecurities and restrictions in the most popular host countries for wartime emigration but are unwilling—for political or other reasons—to return to Russia. Since Latin America is a huge and varied region, our data may not fully represent all dynamics there. Our conclusions should thus be viewed as preliminary insights and warrant further investigation across various national contexts.

Russians in the Latin American Migration System

Latin America is a diverse region stretching from Mexico in Central America to Argentina in the Southern Cone of South America. The region has historically attracted people from the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and modern-day Russia. Indeed, from Trotsky seeking refuge in Mexico City to important centers of Russian monarchism in Argentina and Brazil, Latin America has a rich history of Russian political emigration.

To assess the recent influx of Russian migrants to Latin America, we draw on several sources of empirical data. The first is data from OutRush, a longitudinal survey of Russian emigrants now residing in more than 100 countries.[1] The second consists of a dataset of statistical data produced by migration authorities of several countries in South America, which we accessed through public repositories or through transparency laws. We also rely on a set of qualitative data obtained from in-depth interviews and sociological observation of Russian migrants in Brazil who relocated following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[2]

While Russian migrants to Latin America since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine have diverged from their predecessors by finding their own paths in the region rather than integrating into existing Russian communities, they find themselves operating within broader migratory dynamics in the region. These include such complex migration trends as South-South migration flows, internal forced displacements, and massive transit migration using the Latin American region as a transitional step en route to the United States.

For instance, irregular border crossings by Russian citizens from Mexico into the United States totaled more than 30,000 by March 2023. It is common for Russians who are unable to obtain U.S. visas to travel to Mexico by plane and then continue their journey to the US by land. With the rise in the number of crossing brokers and the increasing availability of information about the crossing on Russian-speaking digital networks, the Mexican border authorities have become more suspicious of Russians traveling to the country. As a result, they have intensified preventive surveillance and detentions in international airports.

Undoubtedly, what makes Latin American countries attractive to new Russian migrants is their visa-free regimes. By 2019, the Russian Federation had visa-free agreements with all the countries in the region. The absence of visa requirements means that people can relocate to these countries quickly in emergency situations as long as they have the money to do so.

Among the most popular countries in Latin America for Russians are Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. This could be attributed to the presence of small Russian-speaking communities in these countries that provide newcomers with helpful information and support. Not all Latin American countries are seen as desirable destinations by new Russian emigrants, perhaps due to a lack of knowledge about the region.

According to the Mexican government, 3,756 residency permits (both temporary and permanent) have been granted to Russian citizens in the last two years (see Figure 1). In the case of Argentina, 889 residency permits were issued in 2022 and 2,402 in 2023. Brazil, which is much less discussed in international media, has also attracted a flow of Russian citizens since the invasion. In 2022 and 2023, Brazilian authorities issued 2,243 residency permits to Russians. Chile has been less popular among Russians, who obtained 197 residence permits in 2022 and 299 in 2023.

Although these numbers do not represent a significant migration flow compared with the exile communities in Georgia, Armenia or Turkey, we observe a stable and significant increase starting in 2022. This indicates that more and more Russians are considering Latin American countries as destinations for permanent or strategic relocation.

Figure 1. Increasing Number of Residency Permits Issued to Russian Citizens in Latin American Countries, 2020-2023

Source: Compiled by the authors on the basis of official datasets. For Mexico: Gobierno de México, Unidad de Política Migratoria, Registro e Identidad de Personas. For Argentina: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Argentina, Portal de datos migratorios en Argentina; For Brazil: Brasil, Polícia Federal, Sistema de Registro Nacional Migratório (SISMIGRA) and Brasil, Ministério de Justiça e Segurança Pública, Sistema de Tramitação de Processos de Refúgio (SISCONARE). For Chile: Servicio Nacional de Migraciones, Departamiento de Estudios, Datos Abiertos de Residencias Temporales y Residencias Definitivas.

Russians in Latin America: Families with Legal Migration Status

The general socio-demographic characteristics of Russian migrants in Latin America[3] do not differ significantly from those of Russian migrants in other countries. They are highly educated, urbanized, and wealthy, with a balanced gender composition (see Figure 2). They remain closely connected to affairs and families in Russia; even if they communicate slightly less frequently (87 percent vs 91 percent) with relatives and friends in Russia, almost half of migrants to Latin America discuss politics with those back home. Despite the distance, they plan to or are already commuting to their homeland, even more frequently than those in Georgia. Interestingly, the distance from home does not provide any assurance against persecution by the government upon their return (see Figure 3). In our sample, migrants in Latin America are as afraid of persecution as those in other destination countries.

Figure 2. Socio-Demographic Differences: Russian Emigrants in Latin America and in All Other Countries

Source: Compiled by the authors on the basis of OutRush survey data.

Figure 3. Social and Political Differences: Russian Emigrants in Latin America and in All Other Countries

Source: Compiled by the authors on the basis of OutRush survey data.

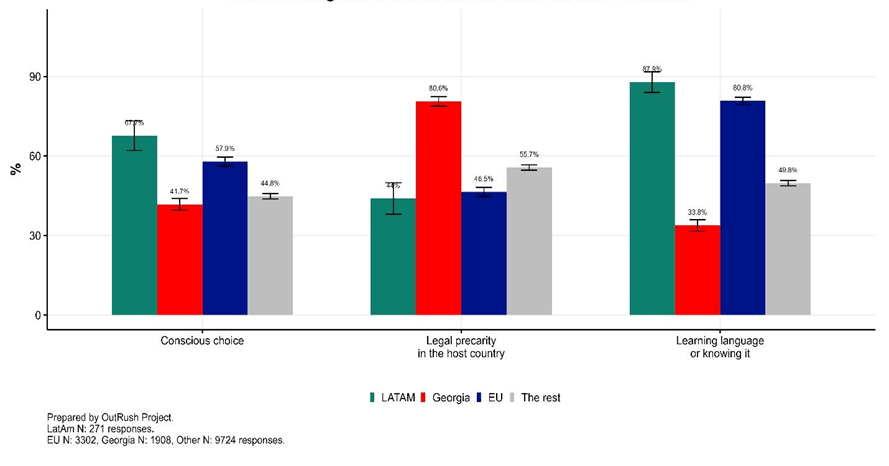

Importantly, however, and in contrast to almost all other countries and regions, migrants rarely choose Latin America as their destination at random (see Figure 4). Two-thirds of respondents consciously chose countries in the region for several reasons: freedoms, distance from the Russian regime, and easy access to citizenship.

Figure 4. Differences in Migration Experiences: Russian Emigrants in Latin America and in All Other Countries

Source: Compiled by the authors on the basis of OutRush survey data.

The ease with which it is possible to acquire citizenship of Latin American countries contributes to a distinctive characteristic of the flow of Russian migrants to the region. Namely, Russian emigrants in Latin America are, per the OutRush data, eight percent more likely to be in an official partnership and have a 12-percent higher incidence of having children compared to their counterparts in other countries. These findings align with the statistical data available for Brazil, which shows that 57.2 percent of Russians with permanent residency permits issued between 2022 and 2023 were aged 26-40, with a further 21 percent comprising children under 15 years old. The same dataset indicates that among the adults, 63.5 percent were married.

Many Russian emigrants choose Latin American countries due to the comparative ease with which children born in these countries can obtain citizenship under jus soli. While not all Russians have relocated around the birth of a child (in Brazil, for instance, asylum claims from Russian citizens increased 1,000 percent in 2022), we can reasonably argue that “birth tourism” comprised a considerable part of the flow. Both in Brazil and in Mexico (for which we have available data), nearly 70 percent of all residency permits obtained by Russian citizens between 2022 and 2023 were based on the family reunification scheme for those married to or parenting national citizens.

The region’s jus soli citizenship laws, combined with the family reunification scheme, mean that migrants who have a child there automatically receive permanent residence permits and become eligible for fast-track naturalization. Reflecting this, the OutRush data show that legal precarity in Latin America is lower than in any other region (see Figure 4).

New Russian communities in Latin American cities are typically dynamic. Those who come exclusively for childbirth stay for approximately three months, while those who apply for citizenship may stay for years. Notably, however, this birth-centered circulation has engendered a broader migration flow of individuals not coming for childbirth. In migration studies, this phenomenon is known as the “cumulative causation” effect: a growing migrant community improves the availability of information, strengthens new social networks, and boosts the ethnic economy in new destination areas, in turn encouraging more migrants to choose that destination.

What Does Additional Citizenship Mean for New Russian Emigrants?

If it is a passport that new Russian emigrants seek in Latin American countries, what meanings do they assign to this additional citizenship? Our findings suggest that the decision to acquire another citizenship is driven by disappointment in and mistrust toward the Russian state and its future. Although the right to travel visa-free is the most popular answer, it is not pragmatic (in the sense that most people do not need it to travel for work or other reasons) but rather related to lifestyle choices. We therefore argue that there are more complex and political motivations for seeking Latin American citizenship than the oft-repeated claims of a desire for a “strong” passport that allows for visa-free visits to more than 170 countries.

Our interlocutors make two broad types of arguments. First, they see additional citizenship as a means by which to enhance their children’s future work and educational opportunities. They frequently express negative assessments of the effects of Russia’s isolationist strategy on their children’s future:

“I just wanted the children to have more choices in the future. To be able to travel more, to live more freely. Learn languages, study in another country.”

“Everything is changing so rapidly that they say that those who can be flexible and adapt win.”

Second, taking a negative view of Russia’s economic and cultural development since the invasion of Ukraine, interlocutors see additional citizenship for themselves as a kind of insurance against the erosion of liberal values and citizens’ rights.

“[I want to acquire citizenship of this country because] this is a country that respects the human person regardless of…”

“This is an additional option because it’s not yet known what will happen to Russia. If it is closed, cut off from the world, as it was in the Soviet Union, we will have no choice.”

“I know that Brazil never extradites its citizens.”

Respondents who pursue this line of argument usually refer to the lack of individual liberties in Russia and their mistrust of the Russian state. While they might not currently be at risk of persecution for political or activist activities, they invest in alternative citizenship as a way to guarantee safety in a future that is seen as blurred and obscure.

Contra contentions that Russians pursuing Latin American passports are being opportunistic and exploitative, we find that they are seeking protection in the context of deepening Russian authoritarianism. In a sense, therefore, this migration is also political, as it is largely a response by a group of wealthy and autonomous migrants to the political situation in Russia. A residence permit for a Latin American country represents a safe route to legal relocation, thereby offering migrants a sense of stability regarding the future.

What to Expect Next?

Given that the Russian government does not plan to abandon its military aggression against Ukraine, nor its persecution of the political opposition and any activists, social movements, or individuals who oppose the war, we can suppose that many Russians will seek to remain abroad. That being said, those who have relocated may find themselves coming under pressure from their host governments: The influx of Russian migrants has sparked public debates in such countries as Georgia, Sri Lanka, and Argentina, while increased irregular border crossings at the Mexico-US border have provoked stricter migration controls on Russian citizens. An additional push factor for relocation may come from the efforts of the Russian consular authorities to reach active or visible Russian dissidents in foreign countries. In the context of shrinking options for relocation, Latin American countries—with their visa-free regimes—could become more attractive for those who are already abroad.

Within South America, we can envisage a remigration from Argentina to Brazil and other countries in the region. In June 2023, Argentina introduced stricter requirements for applying for a “digital nomad” visa, a move that impacts Russians. The unique aspects of Argentina’s naturalization process, which is judicial and potentially unpredictable, may further deter migrants. In contrast, Brazil’s administrative naturalization process is based on objective criteria. Additionally, Argentina’s political and economic instability may appeal to those earning in dollars, but not to those seeking long-term stability or local employment. We are already seeing Russian families relocating from Buenos Aires to Florianópolis for childbirth or residence.

Any assessment of the impact of relocation on local communities should also consider that relocating Russians often have incomes above the local average. Their capital transfers and investments in the local real estate market can lead to transnational gentrification, as observed in Georgia. For instance, in 2022, Rio de Janeiro experienced an influx of Russian capital into the luxury real estate market. On the other hand, in the long term, local economies can benefit from the influx of young, high-earning, high-skilled migrants seeking to relocate their assets to more stable political contexts.

Conclusion

The new Russian emigration extends far beyond European countries and Russia’s neighbors. Since 2022, a growing number of Russian citizens have relocated to Latin American countries. Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile have been their main destinations in the region.

A key feature of this migration is its family-centric nature. Many Russian migrants choose Latin America specifically to give birth and raise children, drawn by the region’s relatively straightforward processes for obtaining legal status and the fast-track naturalization available through jus soli citizenship laws. The choice of Latin America as a destination therefore appears to be comparatively deliberate and strategic, suggesting that Russian families who relocate here are likely to stay for extended periods.

These migrants are typically young, highly educated, and economically self-sufficient. Despite their significant geographical and cultural distance from Russia, Latin American countries offer young Russian families a crucial escape from the shrinking political and economic freedoms in their homeland. These countries provide a new environment in which they can secure better opportunities for their children, free from the constraints and uncertainties imposed by the current Russian regime.

Svetlana Ruseishvili is an Associate Professor at the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil, and a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science, UK.

Ivetta Sergeeva is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute in Florence and principal investigator of the OutRush project.

Emil Kamalov is a PhD researcher at the European University Institute in Florence and principal investigator of the OutRush project.

Sergeeva and E. Kamalov are grateful to their colleagues V. Kostenko, R. Nugumanova, and M. Zavadskaya for their collaboration in data collection

[1] OutRush is a panel comprising three survey waves with more than 10,000 participants. For this memo, we used data from the third survey wave, conducted between May and August 2023. Survey respondents were recruited through online communities, snowball sampling, and researchers’ own networks. Respondents who indicated that they resided in Latin American countries at the time of the survey were asked a special block of questions tailored to participants from the region. As only 271 respondents resided in Latin American countries, we cannot claim that the data are representative. However, we believe it may be useful for understanding general trends about these populations. See: Ivetta Sergeeva et al., “OutRush: Third Wave of the Panel Survey of Emigrants Who Left Russia after the 2022 Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine [Dataset],” European University Institute, 2023. Release January 2028.

[2] “Births and passports” (FAPESP, 2023/03070-1) is ethnographic research with Russian families traveling to Brazil for strategic births. We conducted 24 in-depth sociological interviews between 2019 and 2023, as well as ethnography of Russian-speaking digital networks in three Brazilian cities.

[3] Since the Mexican case is unique due to the flow of Russians entering the country in order to continue on to the US, we will focus primarily on the Brazilian and Argentine cases, which are similar in terms of the socio-demographic profile and motivations of new Russian migrants.