(PONARS Policy Memo) On May 7, 2015, three servicemen of the Ukrainian armed forces went on a mission to find separatist collaborators in Sartana, a small town in the Donetsk region. They forced one randomly detained suspect into the trunk of their car, took him to a clandestine interrogation site in the nearby town of Hnutove, and asked him to list all known separatists. After the suspect repeatedly refused, he was brutally beaten and left dying on the outskirts of a neighboring village. Following the discovery of his body, the servicemen were promptly arrested. However, one year later, all three were decorated with honorary awards for the defense of Mariupol and one of them even received a medal “for courage” by presidential decree. State decorations became the basis for lighter sentences.[1] One soldier was released on probation and the other two served only one year of jail time.

This policy memo examines the causes and implications of the ongoing practice of physical integrity rights violations committed by state agents and affiliated paramilitaries in government-controlled Donbas. It suggests that persistent repressive practices against local civilians undermine the credibility of the state in that region, create additional barriers for settling the conflict, and may foreshadow the broadening of the range of targets to include regime opponents.

Targets and Types of Abuse

For most of its twenty-five years of independence, Ukraine has been classified as a “partly free” state with a medium level of restrictions on civil liberties.[2] However, since 2014, its score on the “political terror scale” has increased from medium to high, indicating that “murders, disappearances, and torture are a common part of life.” While this deterioration can be partially attributed to widespread human rights abuses on rebel-held territories, the application of physical coercion has also become a standard element of Ukraine’s counterinsurgency tactics.

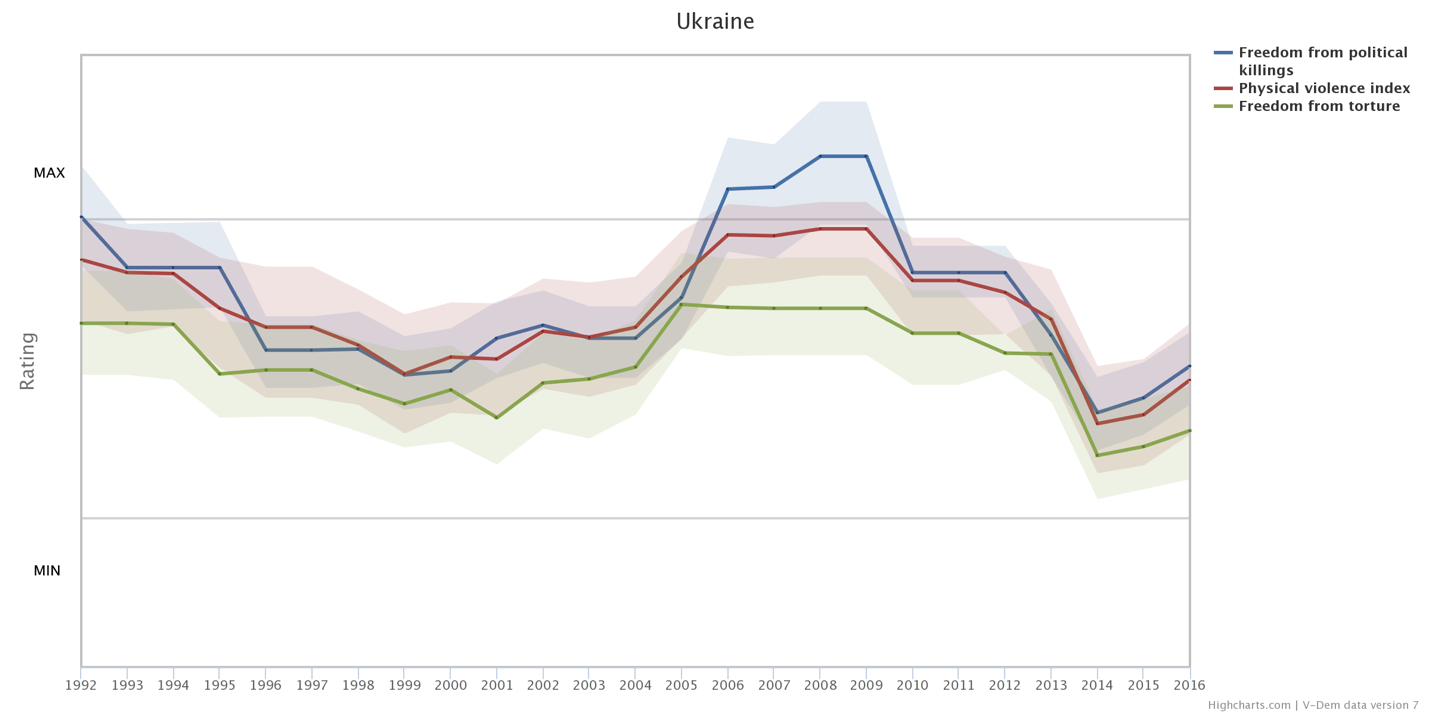

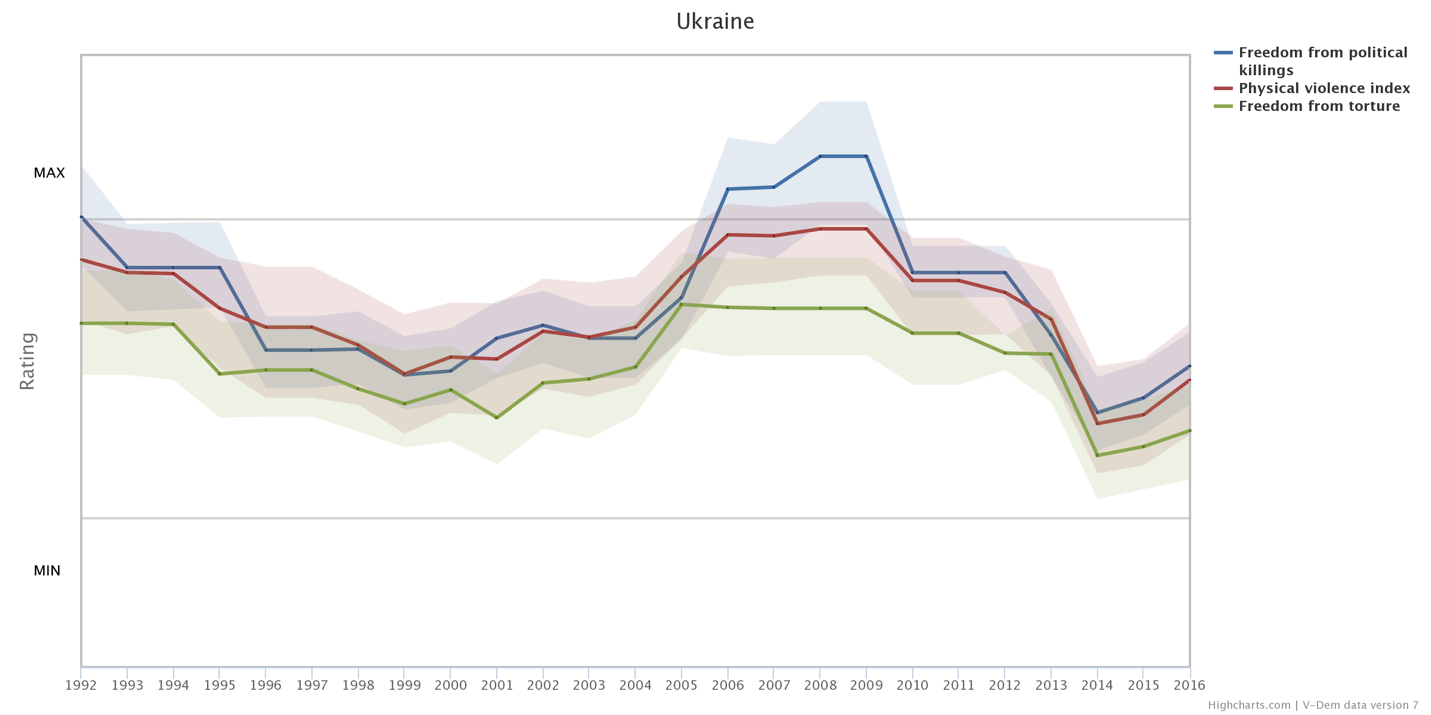

As an index created by V-Dem project shows, violence committed by government agents in Ukraine for the last three years has been at the highest level since the country’s independence (see Figure 1). Reports by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) remain the single most extensive source of information on physical integrity rights violations in Ukraine committed by government agents and their affiliates. The first evidence of enforced disappearances in Donbas by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) was reported in August 2014 with new episodes cited in every report since then. By August 2016, OHCHR concluded that the “Ukrainian authorities have allowed the deprivation of liberty of individuals in secret for prolonged periods of time.” Human rights monitors established that there is “a network of unofficial places of detention, often located in the basements of regional SBU buildings” not only in towns of Donbas, but also in Kharkiv, Odesa, Zaporizzhia, Poltava, and other cities. The authorities relied on volunteer battalions, particularly Azov and DUK Right Sector, to capture separatist suspects and interrogate them at their military bases before transferring them into government custody. Incommunicado detention has become an ordinary practice before suspects are officially registered in the criminal justice system. Some of the victims were taken into custody again immediately after their official release from prison and held in secret locations without charge, often for prisoner exchanges.

Figure 1. V-Dem Physical Violence Index and Its Components in Ukraine, 1992 – 2016

Source: Varieties of Democracy Dataset 7.1

Detainments and interrogations have been usually accompanied by threats, beatings and torture meant to extract confessions of collaboration with rebels, acquire information, or simply punish people for suspected transgressions. The torture practices mentioned in OHCHR reports covering August 2014-June 2017 include the application of electric shocks, suffocation using gas masks and plastic bags, beatings with rubber hammers and sticks, waterboarding, mock executions, hanging with hands tied behind the back, food and sleep deprivation, and standing in a stress position against a wall. In June 2017, OHCHR characterized the use of torture and ill-treatment by SBU operatives against conflict-related detainees as “systematic.” Detained individuals have also been threatened with sexual violence and killing of their family members. After repeated appeals to the Ukrainian government, OHCHR concluded that the “authorities are unwilling to investigate allegations of torture particularly when the victims are persons detained on grounds related to national security or are viewed as being ‘pro-federalist.’” According to OHCHR, this signals to perpetrators that “they are immune to responsibility for human rights violations perpetrated against conflict-related detainees.” OHCHR also collected evidence of extrajudicial killings committed by Ukrainian servicemen and deaths resulting from torture of separatist suspects. It estimated that by May 2016, at least 115 individuals have been victims of “arbitrary deprivation of life, summary and extrajudicial executions and deaths in detention.” Reports issued in 2017 mention two cases of extrajudicial killings and new instances of torture in government-controlled towns in Donbas, which indicates the recurrent nature of these practices.

Why Repression in Ukraine?

The location and selection of targets clearly links heightened repression to the armed conflict in Donbas. Violence by incumbent forces has been based on political cleavages that became salient during protest mobilization in Donbas prior to the outbreak of the armed conflict. The primary victims of abductions, torture, and executions were those suspected of supporting autonomy rights for the region or its separation from Ukraine. Ascription of a “separatist” identity became a common justification for egregious violations of individual rights and actions outside of normal judicial process. Confinement of violence against civilians to areas with potentially large number of separatist sympathizers resembles the dynamics of violence in other civil wars. This is also consistent with an earlier finding that civil war is the best predictor of the rise in a government’s repressive practices. Civil wars have also been shown to exacerbate the effects of a hybrid regime (like Ukraine’s) with risks of repression increasing faster in such systems than in full democracies or autocracies.

One of the mechanisms that set in motion the current repressive cycle was the proliferation of volunteer battalions that were loosely controlled by the government at the early stage of the conflict. According to one comparative analysis, the rise of paramilitary groups during an armed conflict substantially increases the incidence of physical integrity rights violations. Although only some of the battalions in Ukraine were implicated in human rights abuses, OHCHR contends that during the first year of the war, paramilitary groups, often in cooperation with the SBU, became their most frequent perpetrators. This follows a similar pattern of the use of paramilitaries in other conflicts where an overextended state delegates some of its monopoly on coercion to non-state actors, who are often incentivized by extremist ideologies. It also offers them access to military resources and a degree of impunity for their actions. This further allows government to shift responsibility for some of the most egregious crimes on to semi-private militias while still deriving strategic benefits (in the form of information extraction or elimination of opponents) from the illicit actions. Ukraine’s case also shows how repressive practices set in motion by paramilitaries had been perpetuated by the security service. The SBU has been responsible for most of the abuses since late 2015 after the president appointed Vasyl Hrytsak as the agency’s chairman. Earlier, Hrytsak was the head of the anti-terrorist center and characterized by President Petro Poroshenko as the “director of war.”

The key factor that allowed the Ukrainian authorities to sustain the practice of extrajudicial violence was the lifting of internal and external constraints on state repression. The government has routinely accused its critics in the media and civil society of being “the enemy’s fifth column” and threatened to prosecute them. There has been widespread fear of retaliation among those who witnessed abuses by the paramilitaries. This encourages self-censorship in the media, restricts critical reporting on human rights violations, and prevents public awareness of the scale of the problem. Another factor sustaining state repression has been complaisance of horizontal accountability institutions, such as the legislature or judiciary. Rather than demanding an end to illicit practices, some parliamentarians have successfully interfered with the courts to end any ongoing investigations of civilian maltreatment. The courts have been similarly responsive to political pressure from top government officials by delaying hearings, issuing conditional sentences, and dismissing the most serious charges. Finally, there were no pubic criticisms of the government’s poor human rights record from Western leaders. This is a particularly glaring omission since consistent violations of human rights and unrestrained executive are emblematic of the country’s authoritarian backsliding.

Impact and Implications

The persistence of repressive actions against civilians in Donbas has three main implications for the near-term trajectory of Ukraine’s political regime and the prospects of settling the conflict.

First, it may be indicative of additional discretionary powers and greater institutional autonomy of the security service after the president put Hrytsak, his long-time loyalist, in charge of the SBU. Being shielded from any independent, external oversight enables SBU officers to obtain informal rewards through extortion of private companies or create advantages for affiliated businesses. This mutually exploitative relationship, built on the contracting out of extrajudicial violence in exchange for access to rents, may foreshadow a broader violent crackdown on the opposition if uncertainty around Poroshenko’s re-election prospects increases. There has already been growing interference by the security services in the work of civil society activists and journalists. The need to widen the net of targets is often driven by fear among coercive agents of accountability following a power transfer and the loss of control over the flow of rents. Succession crisis may thus lead to the elevation of unelected security officials to state leadership positions. Selective repressions in Argentina against suspected guerilla sympathizers in the 1970s became a prologue to military dictatorship and a “dirty war” against the opposition in which tens of thousands perished. Paramilitaries, some of whom are already threatening violence if their political opponents return to power, may play the role of willing executioners in sweep operations against opposition figures. If the crackdown on civil liberties spills over into the area of basic political rights, Ukraine’s current authoritarian backsliding will transform into a full-fledged authoritarian reversal.

Second, the outbreak of the armed conflict in Donbas was partially the result of a deep legitimacy crisis of the post-Maidan Ukrainian government. After restoring control over most of the region, the Ukrainian authorities failed to create a legitimate foundation for the new political order. The latest IRI poll shows that only ten percent of respondents in the government-controlled areas of Donbas agree that the Ukrainian government was doing enough to keep their territory within Ukraine. According to the same poll, the top five most favorably viewed politicians in Donbas are all former leaders of the Party of Regions (PofR). The unfavorable rating of one PofR stalwart, Oleksandr Efremov, who has been jailed on separatist charges for over a year, remains far below that of President Poroshenko (47 percent versus 78 percent). Recurrent abuses by the security forces and lack of judicial redress can only deepen distrust and resentment toward the state. Although the majority of residents in the government-controlled areas of Donbas prefer unity with Ukraine, the sense of political exclusion combined with the region’s economic devastation means that relative stability and peace there rest on a highly precarious basis.

Third, the impunity of security services, transformation of paramilitaries into semi-private armies equipped with tanks and artillery, and lack of external constraints on their actions represent a major obstacle to the settlement of the Donbas conflict. One of the main barriers to peace is the lack of credibility behind the government’s promises to enforce power-sharing agreements or provide amnesty to former rebels. The three-year track record of human rights abuses against suspected separatists raises questions not just about the authorities’ capacity, but also their willingness to stand by the terms of the peace agreement. Given the personal risks to tens of thousands of people now associated with rebel governance in DNR/LNR any peace settlement is highly unlikely to get implemented.

There are still remedies available to the Ukrainian government. It can gain credibility as a negotiating partner in the Minsk process by ending its practice of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial violence. It can create an independent commission to investigate crimes listed in OHCHR and other reports and collect testimonies from victims. It can also establish strong, independent oversight of the security services by the parliament, anti-corruption agencies, and civil society organizations. It could send a stern message by dissolving and disarming military units linked to far-right political forces.

These measures however, would undermine Poroshenko’s institutional power base and leave him without a key coercive resource ahead of the presidential election (scheduled for March 2019). To reach an agreement, however, he would still need to make tangible concessions to the separatists, which could trigger a backlash from the far right and destabilize his rule. As a result, for Poroshenko, the individual benefits from continuing repressive practices may far outweigh the political costs associated with his failure to take real steps to end the war. This calculation will have a major effect on the outcome of conflict-resolution efforts and the dynamics of the presidential election campaign.

Serhiy Kudelia is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Baylor University.

[PDF]

[1] See the text of the court verdict, Case No. 264/6729/15-к, November 7, 2016: http://www.reyestr.court.gov.ua/Review/62506424 (in Ukrainian and accessible in Ukraine).

[2] Ukraine was in the “free” category only for four years following the Orange Revolution, see: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2017/ukraine.