Ukraine’s resilience to Russia’s war of aggression came as a surprise to politicians, experts, and the general public worldwide. Popularly labeled “invincibility,” Ukraine’s state and societal resilience made the country an “inspiration to the entire free world” and sparked researchers’ interest in the factors/reasons behind it. While many scholars point to national unity, an increasingly salient component of this debate is resilience at the level of territorial hromadas (territorial communities). Here we investigate the enablers of three dimensions of local self-governments’ resilience: preparedness, robustness, and adaptation. In other words, we inquire what has helped local self-governments to be prepared to absorb shocks, adapt to new circumstances, and stay robust without losing the ability to fulfill their basic functions.

We find that hromadas’ resilience is attributable to the decentralization reform in Ukraine, implemented since 2014 with a view to expanding their competencies and strengthening their financial and technical capacities.[1] We identify specific factors that determine hromadas’ resilience to a wide range of risks affected by the invasion. Economic factors (the hromada’s income), the population, and the presence of business hubs affect preparedness; the type (urban/rural) of the hromada influences robustness; and such social indicators as cooperation agreements and voter turnout contribute to the adaptation dimension of resilience. Our research was conducted between March and November 2022.

Hromadas with Real Power

Hromadas exercise local self-government, which is legally defined as both the legal right (guaranteed by the state) and the practical capability of the hromada to solve issues of local significance independently.[2] Hromadas can exercise such rights both directly and through local councils and their executive bodies.

Ukraine’s hromadas acquired broad competencies following the decentralization reform that began in 2014. The decentralization process commenced with the voluntary amalgamation of 1,070 hromadas during the period spanning from 2015 to 2020. It culminated in 2020 with the holding of local elections and the ultimate establishment of 1,469 hromadas, effectively partitioning the entire territory of Ukraine into these administrative units. The key idea behind the reform was to enhance their capacity by first amalgamating them and then broadening their competencies and expanding their access to financial resources. Thus, the executive bodies of local councils became responsible for service provision in the domains of education, culture, health, etc.; they also gained strategic planning powers. To support this, the share of personal income tax received by village and town settlements was increased from 25 percent to 60 percent, before being raised to 64 percent in 2022. Furthermore, following the 2014 decentralization reform, 100 percent of the excise tax on the retail sales of tobacco and alcohol products and 13.44 percent of the excise tax from fuel now remain in the hromada budget.

These changes have created a new social contract between citizens and local administrations that fosters mutual trust: by paying taxes into municipal budgets, local residents and businesses become “principals,” enabling them to demand quality public services from their “agents” (local administrators) in exchange for tax increases. Decentralization has also brought about a shift from state-oriented planning to local stakeholder involvement: as of January 2022, approximately 43 percent of hromadas had produced their own development strategies.

Prepared, Robust, and Adaptable: Dimensions of Resilience in Wartime Hromadas

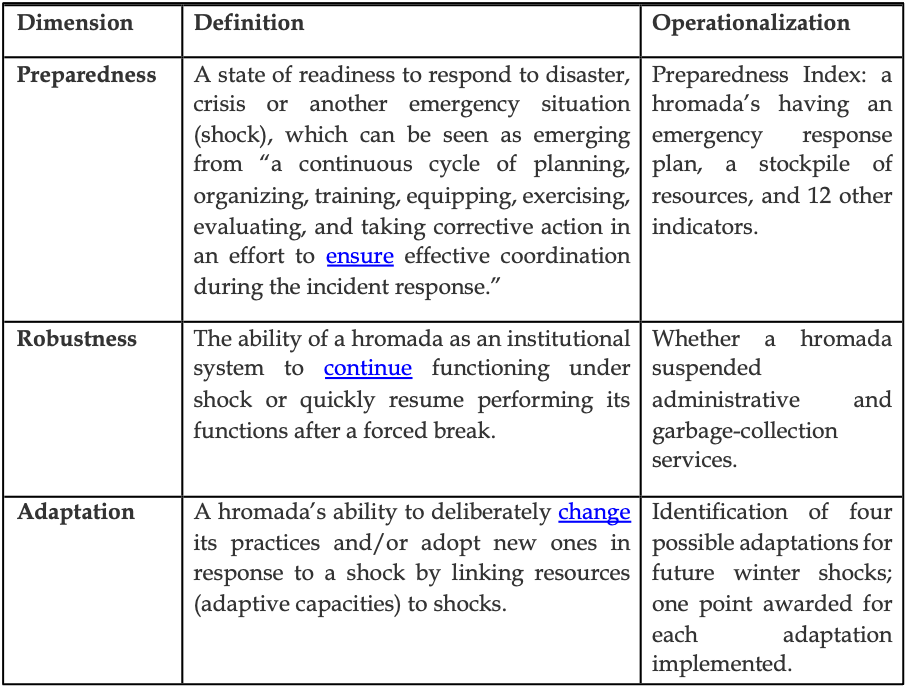

Drawing on eight interviews with local authorities—representing both hromadas that have experienced occupation or direct military action and those that are more distant from the frontline—we identify seven types of shocks experienced by hromadas: institutional, security, economic, humanitarian, critical infrastructure, informational, and early recovery issues. In light of these interviews, as well as the existing literature,[3] we understand hromadas’ resilience to threats to institutional stability as comprising three aspects: preparedness, robustness, and adaptation. We define these terms and provide our operationalization in Table 1.

Table 1. Conceptualization of resilience to threats to institutional stability

Methodology

The study was conducted using a mixed-methods approach. It used qualitative methods, such as exploratory interviews with representatives of local authorities in Ukraine and focus groups with Ukrainian and foreign experts on decentralization, to explore hromadas’ wartime experiences and operationalize both the concept of resilience and its predictors. Surveys of local authorities were then used to gather information on the shocks experienced by hromadas and their wartime practices. We combined these data with open-source data to apply regression models. We tested which independent variables (demographic, economic, and social capital factors) had a statistically significant effect on the dependent variable of institutional resilience. We had two control variables (namely, whether the hromada was urban or rural and whether it was a war zone or near the frontlines as of June 20, 2022) for a number of indicators: measures to prepare for winter, suspension of garbage collection, and full suspension of administrative services.

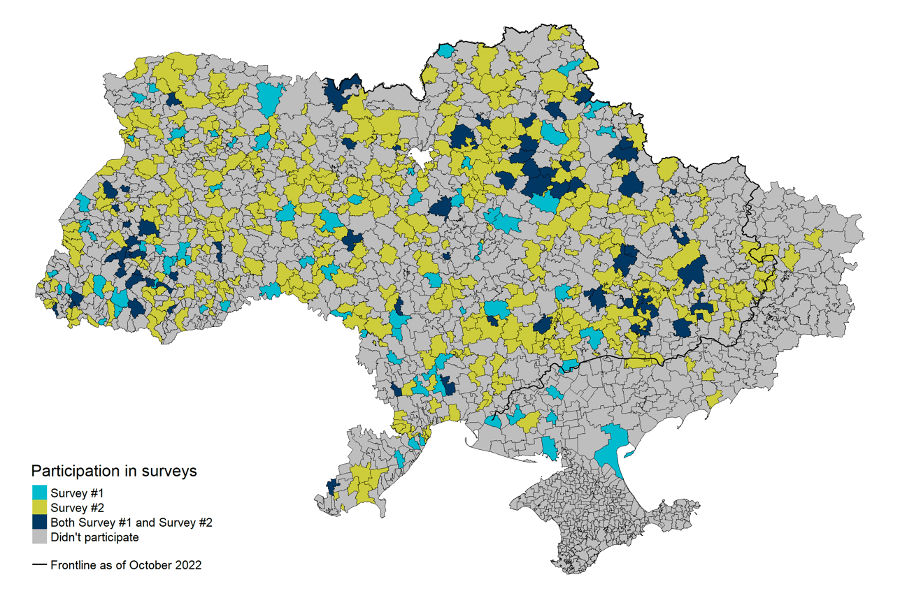

Figure 1. Surveyed hromadas used for operationalization of hromada institutional resilience

Rural-Urban Divide in Preparedness and Robustness

Our findings demonstrate a positive relationship between urbanness and the items that comprise our Preparedness Index. Hromadas with a larger population, an urban type of settlement, and an urban population tend to perform better in terms of preparedness. From this we can infer that prior to the invasion, urban hromadas had greater human and financial capacities to engage and develop existing resources in order to foresee potential shocks, prepare for them, and ensure their functioning.

The converse trend is observed with regard to robustness: more urban hromadas stopped providing administrative services entirely when the war began. From the in-depth interviews we conducted with leaders of hromadas, we learned that the main reasons that hromadas stopped providing administrative services were confusion on the part of hromada leaders (who were waiting for instructions from the central government or lacked an emergency response plan) and the lack of a qualified response on migration by the hromada’s administrative staff.

The economic indicators, meanwhile, point to higher resilience among urban hromadas. The share of their income that is represented by “own revenue” (as opposed to subventions and subsidies from the state budget) is positively correlated with preparedness. This indicator reflects the hromada’s ability to mobilize financial resources from various local taxes, fees, and other sources, making it fiscally self-sufficient and thus an autonomous and efficient actor in the budget system. On average, “own revenue” is seven percent higher in urban hromadas than in rural ones. It should be stressed that it is not the amount of resources available to a hromada but its capacity to generate its own income that influences its preparedness for complex, multi-dimensional shocks. Even though Ukraine’s decentralization reform emphasized the need to build hromadas’ capabilities, rural hromadas demonstrate lower capabilities to generate their own income than urban ones.

Stronger Economies and Longer Experience of Governance as Enablers of Preparedness

Around 13 percent of all hromadas had the status of “cities of oblast significance” prior to the start of the decentralization reform in 2014. Such status was given to cities that were economic and cultural centers, with developed industry, and a population over 50,000 people. These cities were allowed to retain 75 percent of the personal income tax; they were also accorded functions such as strategic socio-economic planning that were, in rural municipalities, assigned to the rayon (district) administration. In using this predictor as a proxy for resource equity and social vulnerability, we aimed to assess whether this longtime divide had influenced the various aspects of resilience.

There is a positive correlation between the presence in a hromada of a “city of oblast significance” and the hromada’s score on our Preparedness Index. We suggest that this relationship (visible even when controlling for the urban or rural status of hromadas) is influenced by the longstanding economic prosperity of these cities, as well as the years of experience in managing substantial financial resources and strategic planning that these cities accumulated prior to the decentralization reform.

Proximity of the Frontline and Russian-Belarusian Borders as Influences on Robustness and Adaptation

The research on hromadas’ adaptation and robustness shows that suspensions of services and a lack of adaptation measures were influenced more heavily by the region (and its affectedness by military actions) than by the type of hromada per se. The probability of experiencing a total suspension of administrative or waste collection services was higher in hromadas situated within the northern macro-region, especially those located closer to the border with Belarus and Russia. At the same time, hromadas positioned in northern regions and closer to the frontline exhibited more favorable outcomes on winter-adaptation metrics than those in southern regions and closer to the EU.

This contrasts with preparedness, where hromadas’ scores on our index were influenced by neither geographic factors nor affectedness by military actions. This observation underscores the multifaceted nature of resilience, highlighting that distinct hromada types might perform differently on different dimensions.

Collaboration Capacities and Democratic Practices as Predictors of Preparedness, Robustness, and Adaptation

Our research on preparedness also revealed the positive role of networks (represented by cooperation agreements) on all three dimensions of resilience. While the number of agreements signed by a hromada over time was an essential determinant of preparedness and adaptation, it was the number of hromadas with which these agreements were signed that determined robustness. Where local governments continue to sign agreements with the same partners over time, it implies that they have the ability to plan. Strategic collaboration between hromadas can play a vital role in enhancing their resilience by allowing them to share resources, expertise, and best practices; fostering collective problem-solving; and enabling coordinated efforts to face external shocks and challenges. In addition, such collaborative endeavors facilitate the pooling of knowledge and capacities, leading to more efficient and effective response strategies.

Additional factors that influenced adaptation and preparedness were the democratic practices of hromadas—exemplified by active participation in local elections—and the establishment of a business support center. Hromadas with higher voter turnout in the 2020 local elections did more to prepare themselves to adapt to future winter shocks, while hromadas with a business support center (a voluntary association of hromada businesses or a specialized hub for business cooperation) scored better on our Preparedness Index.

This testifies to the fact that not only material resources, but also engagement and governance are essential to resilience. In this regard, Ukraine’s decentralization reform—which strove to build the capacity of hromadas and strengthen citizens’ participation at the local level—has been conducive to resilience in the face of the invasion. The decentralization reform has also enhanced resilience by paving the way for knowledge exchange and collaboration between hromadas via collaboration agreements.

Conclusion

Hromadas’ experiences of the invasion have been very different depending on whether they are in the rear, are close to the frontline, or have experienced occupation. Yet given the scale of the invasion and the multiplicity of shocks, all hromadas—not only those close to the frontline or under occupation—have faced threats to their institutional stability.

We find that economic and social predictors of resilience, as well as the urban-rural divide, correlate with hromadas’ preparedness for the invasion, while proximity to the frontline and collaboration capacities are the central factors in hromadas’ robustness and adaptation to threats to institutional stability. Thus, both material and immaterial resources influence hromadas’ ability to cope with the present threats to institutional stability.

The decentralization reform, which made hromadas more capable and less dependent on the center, can be seen as conducive to various aspects of hromadas’ resilience to institutional threats, especially preparedness. Autonomy and ownership of local decision-making gave hromadas greater flexibility in collaborating with one another, as well as in attracting support from outside—inter alia from international partners and donor agencies—than they had enjoyed prior to the reform. The decentralization reform did not, however, manage to fully bridge the urban-rural divide in Ukraine: we find that rural territorial hromadas, especially small ones, have lower capacity to generate their own incomes, in turn detrimentally impacting their preparedness.

Hromadas’ resilience amid Russia’s war against Ukraine testifies to the importance of fostering local self-governments’ economic capabilities (in particular, their ability to generate their own income), social networks, and citizens’ participation in order to improve their resilience to institutional shocks in the context of war.

Andrii Darkovich is a researcher in the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization, and Regional Development at the KSE Institute.

Myroslava Savisko is the project manager for the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization, and Regional Development at the KSE Institute.

Maryna Rabinovych is an Assistant Professor at the Kyiv School of Economics and a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Agder, Norway.

This memo is based on an academic article by Dr. Tymofii Brik (KSE); Dr. Maryna Rabinovych (KSE and University of Agder); Andrii Darkovich (KSE); Myroslava Savisko (KSE); Valentyn Hatsko (KSE); Serhii Tytiuk (KSE); and Igor Piddubnyi (KSE) that is under consideration by Governance.

[1] Tymofii Brik and Jennifer Murtazashvili, “The Source of Ukraine’s Resilience: How Decentralized Governance Brought the Country Together,” Foreign Affairs, June 28, 2022.

[2] The Ukrainian word “hromada” is commonly translated into English as a “territorial community” (this term is, inter alia, used in the official glossary of the decentralization reform. In functional terms, the Ukrainian concept of “hromada” is, however, close to the European one of “self-governed municipality.” We explain the concept and functions of hromadas in the theoretical section of the paper below. In our research, we use the short version “hromada” for the term “territorial hromada” that appears in Ukrainian legislative acts.

[3] Olga Reznikova, “Strategic Analysis of Ukraine’s Security Environment,” Strategic Panorama (2022): 45-53; Gunnar W. Klau and René Weiskircher, “Robustness and Resilience,” in Ulrik Brandes and Thomas Erlebach, eds., Network Analysis (Berlin: Springer, 2005); Fiona Miller et al., “Resilience and Vulnerability: Complementary or Conflicting Concepts?” Ecology and Society 15, no. 3 (2010).

[4] Survey #1 (Agrocenter) was conducted online with the local authorities of hromadas in June-August 2022 and was used to measure robustness by looking at the suspension of services. The total number of responses was 474 (representing 33 percent of Ukraine’s 1,438 hromadas). Survey #2 (ULEAD) was sent online to the local authorities in October-November 2022 to get insight into hromadas’ preparedness for and adaptation to the full-scale invasion. The survey was completed by 138 representatives of hromadas (9.6 percent of the 1,438 hromadas, excluding hromadas that were occupied in 2014). Both surveys were conducted by KSE Institute Centers: Survey #1 was conducted by the Agrocenter and Survey #2 by the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization, and Regional Development. The data can be provided to individual researchers upon request.