The emergence in 2015 of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) on the map of regional integration initiatives occurred in a difficult regional context. The war in Ukraine and ensuing tension in Russian-Western relations were sparked—but not caused—by divisive trade-related matters that began to unfold in 2013. Even before its formal unveiling, therefore, the EEU was thrown into the middle of a major crisis, which focused attention on the geopolitical implications of Eurasian integration.

The latest round of this integration is based on two impulses: real and imaginary. The real EEU is an international economic organization, much like any other. The imaginary one is fueled by geopolitical aspirations, a vision of a Eurasian Union that will not only foster a new round of post-Soviet reintegration but will serve as one of the “building blocks” of “global development”—on par with the EU, NAFTA, APEC, or ASEAN. This Eurasian Union is ultimately to crown Russian President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to reverse the civilized divorce of the post-Soviet states.

The duality of Eurasian integration creates tensions in the union and with external partners, as it is difficult to dissociate the economics of Eurasian integration from its geopolitics.

Eurasian Economic Questions

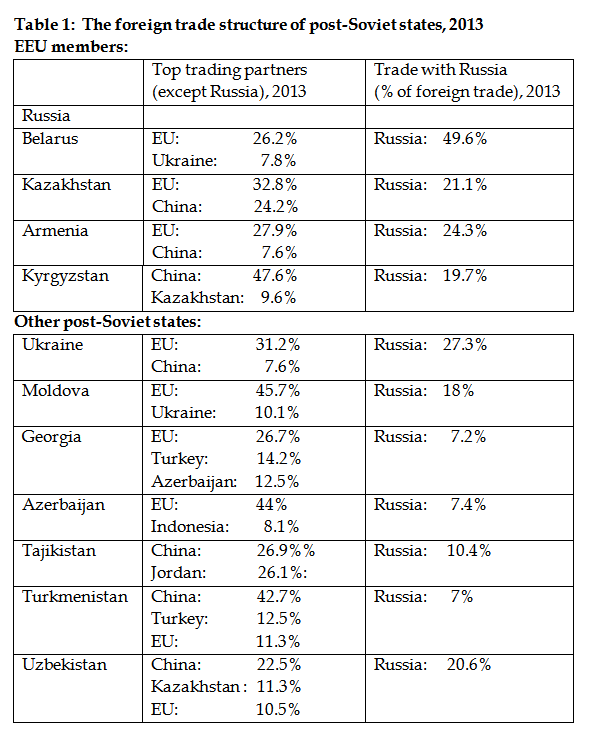

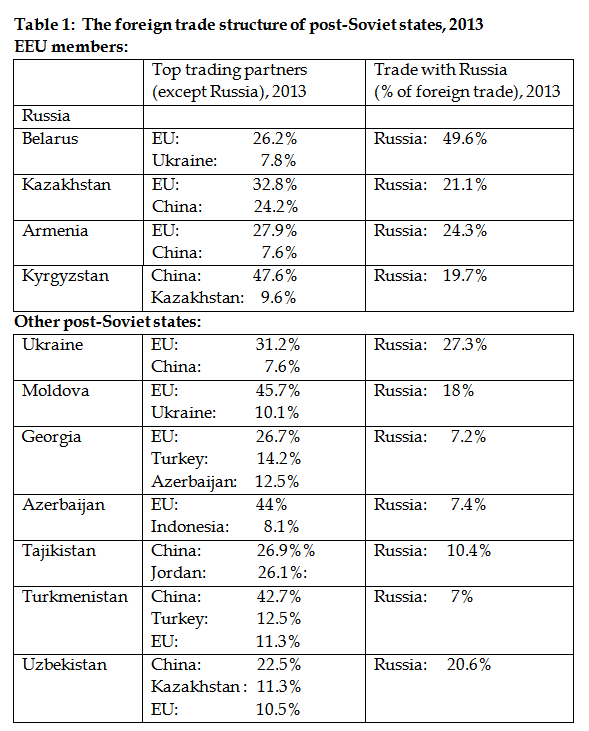

The economics of Eurasian integration itself raises questions. In the two decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia’s weight and importance as a trading partner for most of the post-Soviet states has declined considerably. China’s economic rise and the opening of relations with the EU have profoundly altered patterns of trade in the vast territory of what was once the Soviet Union. For every post-Soviet state except Belarus, the EU and China are now bigger trading partners than Russia. This does not prevent post-Soviet states from integrating, but it does suggest that the economic synergies of this integration may be limited.

Source: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions

This is reinforced by the fact that the record of the EEU’s predecessor, the Customs Union, has not been reassuring. After an initial boost in trade in 2010-2012, trade among Customs Union members Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan has actually been falling. In 2013, it fell by 5.5 percent, in 2014 by 11 percent, and in the first half of 2015 by 25.6 percent.[1] These initial complications might yet be overcome, but they do raise questions about the economic viability of the EEU.

Eurasian Political Questions

Beyond economic considerations, the political foundations of the Eurasian integration initiative are also precarious. On the one hand, Russia is a key driver of the Eurasian integration process and there appears to be a wide degree of elite and public support within Russia for it. While strong on the surface, however, this consensus in favor of Eurasian integration may yet clash with other widely shared ideas and social realities.

The prospect of free movement of labor is probably the single most attractive feature of the EEU from the point of view of most post-Soviet states, particularly in Central Asia, where retaining access to the Russian labor market is a matter of crucial socioeconomic stability. But the issue of migration may be something of a political time bomb inside of Russia. While the Russian government aims to liberalize and open the labor market for EEU members, up to 84 percent of Russians are in favor of restricting the current regime by introducing visas for migrants from Central Asia.[2] Public hostility to migrants from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds has already degenerated on a number of occasions into violent anti-migrant riots.[3]

Nationalist opposition to the EEU has yet to crystallize in Russia, partly because of the popularity of the Crimean annexation and partly because hostile nationalist sentiment is currently directed at Ukraine. Nonetheless, with the passing of the hot phase of the Ukraine conflict, it may not take long for anti-immigrant nationalism to start taking the form of opposition to the free movement of labor in the EEU. Ignoring such sentiments could create new domestic problems. At the same time, failing to deliver on the free movement of labor by adopting tough border and migration policies could create complications among EEU members and undermine one of its key points of attraction.

Eurasian Geopolitical Questions

When asked what Russia wants from the EEU, a Russian expert responded with the (probably false) parable of the boiling frog: “If you throw a frog into boiling water it will jump out, whereas if you put a frog in cold water and heat it gradually, the frog will stay there until boiled. That is the role of the Eurasian Economic Union—to be an economic stepping stone toward a bigger geopolitical project, without raising too many objections too early.” Even if boiling a frog actually worked that way, the heating of the water would need to be very, very slow.

Time, however, may be a bigger problem for the EEU than for potential frog-boilers. The economic disintegration of the post-Soviet space is rather advanced and ongoing. The EU and China have increased their role as external trade partners for most post-Soviet states and are likely to continue doing so, especially with the EU’s creation of free trade areas with some post-Soviet states and China’s “Silk Road Economic Belt” project.

The idea that economic integration can lead to deeper (geo)political union is not a novel one. European integration began with the creation of a common coal and steel market and then expanded into dozens of other areas of cooperation. Throughout its existence, the EU has gone through several rounds of deepening integration and widening membership.

Eurasian integration processes face similar questions but enjoy much less time. There is a serious tension between the real Eurasia (as represented by the EEU) and the imaginary one (as represented by Russia’s vision of a geopolitical super-bloc). On the one hand, the EEU is supposed to be the engine for the future geopolitical Eurasian Union. But for economic integration to function and move forward requires a measured, steady, and calculated approach. This means a small number of countries, a manageable number of internal contradictions, and clear economic benefits.

The logic of geopolitical Eurasia is the opposite. It suggests that the larger the Eurasian Union, the stronger Russia’s great power image will be. The Union’s ultimate form also needs to materialize relatively fast, before Russia loses even more of its economic centrality in the post-Soviet region to China and the EU. But the rush to expand creates the risk that adding too many carriages to the train or pushing the Eurasian engine too fast will break it.

This tension is not new. Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus have tried to manage it by a careful widening and deepening of their integration. That is why the Eurasian Economic Community of six states, launched in 2000, was dropped, and Russia moved ahead with a customs union with the two other states only.

Conceivably time could work in favor of deepening the EEU, but it certainly seems to work against its enlargement. The risk is that the longer the EEU’s enlargement is postponed, the fewer interested candidates there will be since the other post-Soviet states are increasingly tied into other international trade networks and commitments that complicate their potential accession.

Ukraine: The Avoidable Trade Clash?

Take Ukraine, where the tension between EEU enlargement and deepening was most acute. When the EEU was being pre-cooked in 2012-2013, Ukraine was supposed to be the jewel in the Eurasian integration crown. To assuage Ukraine’s fears of a potential loss of sovereignty, Russia dropped the system of qualified majority voting from the Customs Union and moved toward consensus-based decision-making (giving each state veto power) in the EEU. In other words, it traded streamlined decision-making and the imperative of deepening integration in favor of potential enlargement to Ukraine.

In the end, it didn’t work. This was partially for lack of time, as Ukraine was moving toward signing an Association Agreement with the EU, which contained provisions for a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. On paper, Russian opposed the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement on the basis of legitimate trade interests, not geopolitical designs. Russia feared that European exports would be re-routed (and relabeled) via Ukraine to the Russian market, which would let non-Ukrainian exporters circumvent Russian customs duties. It also claimed that the agreements were imposing an “either-or” choice on its signatories, i.e., that they forced countries like Ukraine or Moldova to “choose” between Russia and the EU.

On their own, these two problems could easily have been addressed. The fear of trade re-routing was not unjustified in principle but could have been solved by improved cooperation concerning the rules governing the origin of goods (and not by the kind of major economic and diplomatic offensive that Russia launched against the Association Agreement from mid-2013). Moreover, in May 2015, Russia, Ukraine and the EU actually reached a technical solution to assuage Russian fears by agreeing “to consider initiation of a revision of the rules of origin of the CIS FTA” and “to strengthen the informal dialogue on customs cooperation with Russia and, where requested, provide EU expert advice and technical support to the Parties.” What started with Russian opposition to the standards stipulated in the Association Agreement ended with a Russian agreement to adapt to some of its rules.

As for the supposed “either-or” choice between free trade with Russia and free trade with the EU, this was not a justifiable concern. The Association Agreements were not a challenge to the pre-existing trade relations between Russia and its post-Soviet neighbors. The EU’s free trade area provisions with Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia were compatible with the existing free trade area agreements of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)[4]. Article 18§1 of the 2011 CIS free trade area agreement explicitly states that the treaty “does not preclude participating states from taking part in customs unions, free trade, or cross-border trade arrangements that correspond to WTO rules.” Neither did the Association Agreements impose an either-or choice on Ukraine or Moldova. They stipulate (in, for example, Article 39 of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement) that they “shall not preclude the maintenance or establishment of customs unions, free trade areas or arrangements for frontier traffic except insofar as they conflict with trade arrangements provided for in this Agreement.”

The best illustration of the compatibility of the CIS free trade regime and an Association Agreement is the fact that Moldova currently is party to both (as is Serbia and, possibly soon, Israel). Russia introduced bilateral trade restrictions on Moldova for its signing of the Association Agreement, but Moldova remains a member of the CIS free trade area.

What a state cannot do is have a free trade area with the EU and join the EEU. This is because joining the latter organization implies a delegation of the sovereign right to negotiate tariffs to a supranational level, making it a legal impossibility to enter into independent bilateral (as opposed to EEU-level) free trade deals. However, such an incompatibility was theoretical, insofar as no leader of an AA country, including former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, ever expressed an intent to join the EEU.

In the end, what fueled the Ukraine crisis were not trade-related matters but the pure geopolitical consideration that at some point down the road Ukraine might be “persuaded” to join the EEU. For that option to be available, Russia had to oppose the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, and it dashed to buy time for the EEU to become attractive to Ukraine. This went wrong, not just for Ukraine but also for Russia’s economy and its capacity to act as a political and economic locomotive of Eurasian integration. It has had negative implications for intra-Eurasian trade, the EEU’s economic viability for current members, and its attractiveness to future ones.

Conclusion

The EEU is a reality, but it remains far from being consolidated. Its economic benefits and intra-union trade dynamics have been problematic. The changing patterns of trade interdependence of most post-Soviet states away from Russia (and toward China and the EU) has already complicated the EEU’s potential to be either economically dynamic for existing members or attractive to new ones. These issues have been compounded by the geopolitics of Eurasian integration, which required expansion of the trading bloc before economic consolidation.

The EEU has ended up in something of a catch-22. It was designed as an economic initiative which could gradually achieve geopolitical objectives. But the perceived urgency and prevalence of geopolitics helped precipitate a crisis in Ukraine. This, in turn, has further undermined the potential for Eurasian integration to become a sustainable economic project. Thus, rather than have economic integration bring about geopolitical results, geopolitics has threatened the economic basis for the EEU.

Nicu Popescu is Senior Analyst at the European Union Institute for Security Studies.

Portions of this paper are based on the author’s “Eurasian Union: the real, the imaginary, and the likely,” Chaillot Paper No. 132, EUISS, September 2014.

[PDF]

[1] Eurasian Economic Commission, data for 2013, data for 2014, and data for 2015 (released on July 27).

[2] Levada Center, Opinion Poll on “Attitudes to migrants,” July 3, 2013.

[3] For more, see Nicu Popescu, “The Moscow riots, Russian nationalism and the Eurasian Union,” EUISS Brief no. 42, November 2013.

[4] Georgia is party to the CIS Free Trade Area Agreement, even though it withdrew from the CIS after the 2008 Georgian-Russian war.