(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Both government agencies and civil society activists in Ukraine widely employ anti-corruption messaging such as billboards, posters, television advertisements, and trainings. But which messages, if any, are effective? Surprisingly, despite anti-corruption messaging’s widespread use, systematic evidence that it can effectively change hearts and minds is all but lacking. More perturbingly, scholars have shown how some type of informational campaigns can “backfire,” often by inadvertently enforcing perceptions among citizens that the proscribed behavior is widespread, and therefore implicitly socially acceptable even if harmful.

This memo presents evidence based on a survey experiment embedded in a national survey of Ukrainians and a laboratory experiment conducted with Ukrainian university students. The findings indicate that anti-corruption messaging that emphasizes the success of anti-corruption campaigns (i.e., a “positive” message) may reduce citizens’ willingness to give bribes. By contrast, anti-corruption messaging emphasizing that corruption is a growing problem (i.e., a “negative” message) appears to be less effective and, in some circumstances, may even inadvertently increase citizens’ willingness to engage in corrupt acts.

How Anti-Corruption Informational Campaigns Can Backfire

Informational campaigns are widely considered to be an important tool for promoting change in social norms, and governments and activists across the globe regularly rely on anti-corruption messaging, inspired in part by the highly publicized campaigns pioneered by Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) in the 1970s.

Do such programs work? Unfortunately, the existing evidence is highly limited, and what exists is not particularly promising. Peiffer’s study of Indonesia examined the effect of providing survey respondents with information about the extent of corruption, government efforts to combat it, or citizens’ anti-corruption activism. [1] Regardless of the message, she found that participants in the study became more concerned about corruption’s harms, but less proud of government anti-corruption policies and less confident about individuals’ ability to combat corruption. Meanwhile, Denisova-Schmidt discovered that providing Ukrainian university students with information about corruption in the education sector had few salutary effects on attitudes toward corruption. Instead, among the sub-sample of students who had never personally engaged in corruption, beliefs that corruption is bad declined while beliefs that corruption is a common way of getting things done increased.

These findings are in line with studies showing that informational campaigns, ranging from anti-drug messaging to vaccination campaigns, can backfire. Among other mechanisms behind this effect, some messaging may contribute to the impression that “everyone is doing it,” and therefore an activity must be socially acceptable, even if unlawful or harmful. Corbacho explicitly tested this idea with respect to corruption by showing survey respondents in Costa Rica evidence that an increasing number of their compatriots had been offering bribes in recent years. After exposure to this information, the proportion of respondents willing to offer a bribe was 28 percent higher than the proportion among those who had been shown information unrelated to corruption.

Such findings suggest that information campaigns that enforce the idea—even inadvertently—of corruption being widespread could be particularly dangerous. On the other hand, such findings also raise the possibility that the power of social norms could be harnessed in positive ways if messaging focuses on the ways that corruption is beginning to decrease. The studies discussed below were designed to examine these possibilities.

Anti-Corruption Messaging in Ukraine

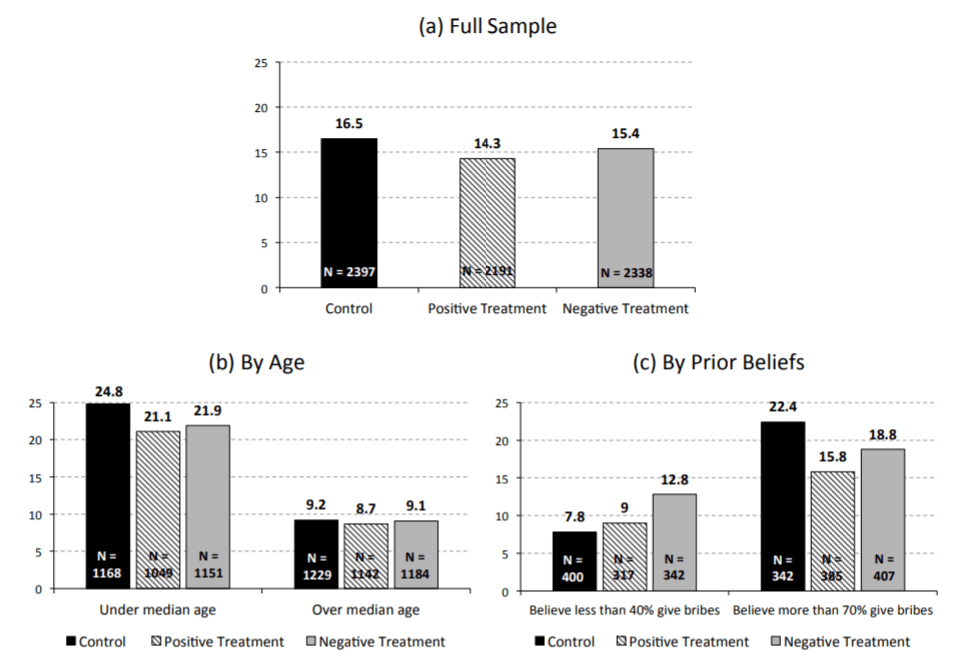

Ukraine currently is in the throes of an anti-corruption campaign, with both non-governmental organizations and government agencies actively utilizing anti-corruption messaging. The image on the left in Figure 1 shows an anti-corruption poster that greets travelers at Kyiv Borispol Airport, announcing the goal of a “Ukraine without corruption!” and reminding passersby that bribery “is a criminal offense.” Anti-corruption posters can be found at bus stops, on billboards, and at numerous other locations. But anti-corruption campaigns in Ukraine also illustrate how such efforts may inadvertently emphasize the ubiquity of corruption. The right-hand image in Figure 1, taken from an online anti-corruption training course, shows ratings of Ukraine’s corruption levels growing worse over time. Similar images, often based on campaigns by well-meaning organizations, regularly are reproduced in the Ukrainian press or spread via social media.

Figure 1: Anti-corruption Messaging in Ukraine

The image on the left shows an anti-corruption poster in Kyiv’s airport. The right shows a flyer from an anti-corruption training course.

Despite this messaging, Ukraine remains a highly corrupt country. It ranked 130th out of 180 countries on the 2017 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index and, according to TI’s Global Corruption Barometer, 38 percent of Ukrainians reported paying a bribe when accessing basic government services in 2016. Ukraine, therefore, presents a particularly tough test for the effectiveness of anti-corruption messaging. Where conceptions about corruption are deeply rooted, it may prove especially difficult to shift beliefs or practices via informational campaigns. Consequently, if anti-corruption messaging proves effective in Ukraine, this bodes well for its applicability on a wider scale.

Survey Experiment

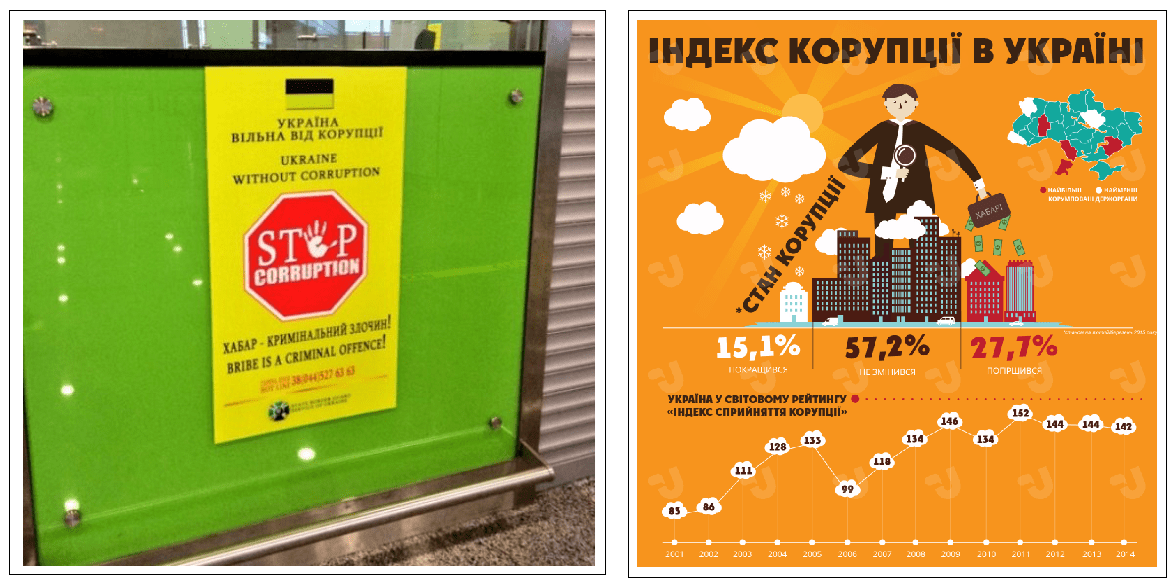

To examine the effectiveness of distinct types of anti-corruption messaging, the first study I conducted employed an experiment embedded in a survey of 6,926 adult Ukrainians during July 2017. One-third of the sample, selected at random, was shown an anti-corruption flyer with a positive message emphasizing how anti-corruption campaigns in Ukraine are beginning to show success, as evidenced by declining rates of bribery. Another third of the sample was shown an anti-corruption flyer with a negative message emphasizing that corruption is a growing problem that needs to be stopped. The final third of the sample was assigned to a “control group” which was not shown a flyer.

Figure 2 shows English-language versions of flyers used in the study. Both flyers have identical formatting and use the same anti-corruption message at the bottom of the page calling on citizens to “Keep fighting—stop corruption.” They differ in that the flyer on the left calls citizens to action by emphasizing how current efforts are contributing to the decline of corruption, while the flyer on the right calls citizens to action by emphasizing that corruption is spreading. The flyers rely on real survey data but draw on different time periods and different sources to emphasize distinct messages.

Figure 2: Flyers for Survey Experiment

Respondents were later asked whether they would be willing to offer a bribe in order to receive a driver’s license more quickly or easily. The rate of willingness to engage in a bribe transaction was then compared across respondents who had been shown the flyers and those who had not.

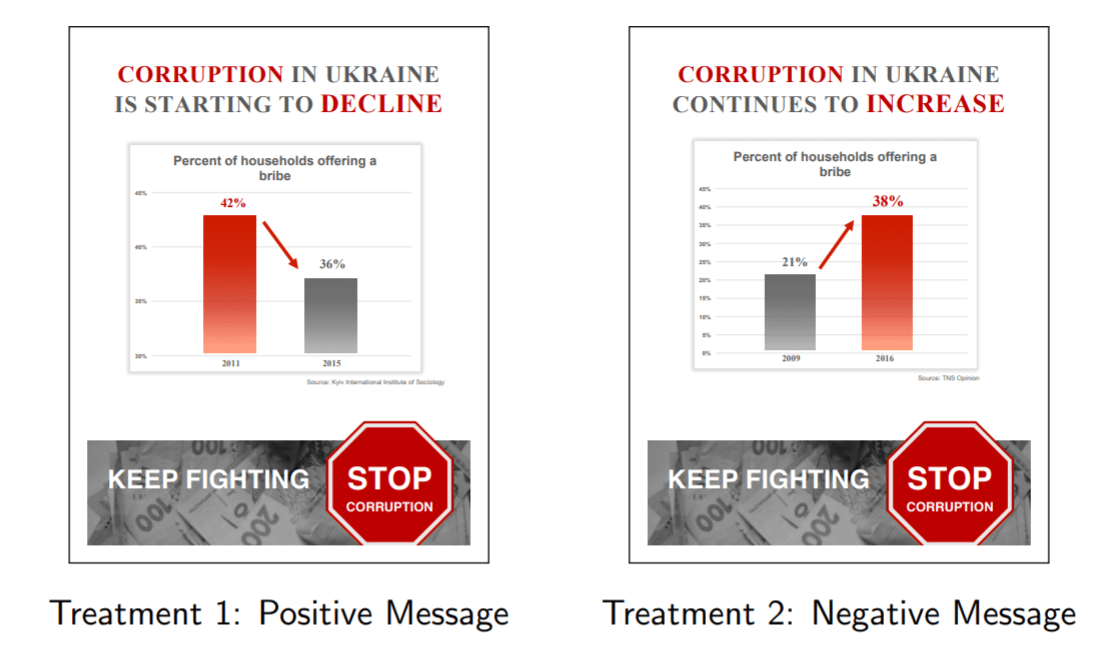

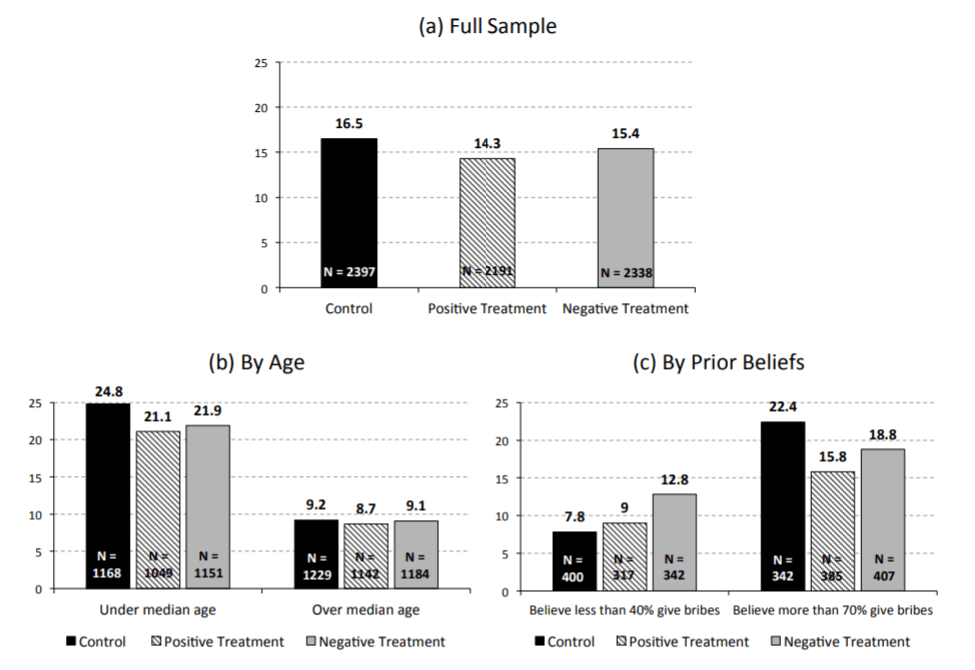

Figure 3, which displays the percent of respondents expressing willingness to offer a bribe, presents the study’s main results. As can be seen in subfigure (a), 14.3 percent of respondents shown the flyer with a positive message were willing to offer a bribe, compared to 16.5 percent in the control group, a 2.2 percentage point decline. By comparison, the decline in willingness to offer a bribe was more modest for the respondents shown the negative message—a 1.2 percentage point decline.

Figure 3: Results of Survey Experiment (Percent Willing to Give Bribe)

Information campaigns, however, are unlikely to affect all citizens equally. Younger people, for example, might be more open to new information. Indeed, when the sample is divided by age, as in subfigure (b), it can be seen that the positive message induced a 3.6 percentage point decline in willingness to offer bribes among younger respondents, from 24.8 to 21.1 percent. The impact of the negative message was also larger for younger respondents than for the sample as a whole—2.8 percentage points—though still smaller than for the positive message. Among older respondents, the flyers had almost no effect, but in part these results from these respondents’ very low initial levels of willingness to offer a bribe.

It might also be expected that the flyers would have a larger effect on respondents who received information challenging their prior beliefs. Subfigure (c) presents evidence to this effect, separately examining the impact of the flyers on those with prior beliefs that corruption in Ukraine is relatively low or relatively high. More specifically, subfigure (c) compares respondents who at the outset of the survey believed that 40 percent or fewer Ukrainians offer bribes (the bottom quartile of the sample with respect to prior beliefs) with respondents who believed that 70 percent or more offer bribes (the top quartile). These analyses should be treated with some caution: the number of observations is limited given that not all participants offered information about prior beliefs. Nevertheless, some striking patterns are apparent.

First, it is clear that respondents’ beliefs about others’ willingness to engage in bribery affect their own propensity for corruption: those believing bribery is widespread are noticeably more willing to offer bribes. Second, for respondents who believed that bribery is widespread, the positive message about bribery declining led to remarkable shift—a 6.6 percentage point decline—in willingness to offer a bribe. The negative message also had a salutary effect, but of a lesser magnitude.

Finally, for respondents who believed that bribery in Ukraine is less widespread, the anti-corruption messages caused something of a backfire effect. This effect was quite modest in the case of the positive message, but exposure to the negative message about rising corruption led to a 5-percentage point increase in willingness to offer bribes, even though this message was framed as an anti-corruption flyer seeking to raise concern about corruption’s harms.

In summary, in the sample as a whole and across sub-groups, the positive message proved more effective than the negative message. Moreover, for some respondents, the negative message had the unintended effect of increasing willingness to engage in a corrupt act.

Laboratory Experiment

The study discussed above measured only respondents’ reported willingness to give a bribe. For obvious reasons, measuring actual bribery is quite challenging. One novel approach to this challenge involves laboratory experiments. These experiments utilize incentive payments—real money—to reveal participants’ preferences by inducing observable behavior. One may question the extent to which lessons from laboratory corruption experiments hold outside the lab, but recent studies have shown a remarkable correlation between in-laboratory choices and real-world behavior.

The bribery game employed in my second study, which builds off of a design developed by Barr & Serra, was conducted with 696 university students at a legal academy in Ukraine during October and November 2017. Participants were randomly assigned to the role of citizen or bureaucrat at the outset of the game, given 35 Ukrainian hryvnia, and then presented with a scenario in which the citizen can increase his/her earnings by obtaining a permit. When he or she seeks to obtain the permit, however, he or she is denied and given a chance to offer a bribe to the bureaucrat. If the bureaucrat accepts the bribe and the citizen receives the permit, both participants earn higher payoffs, but if a citizen encounters an honest bureaucrat, then offering a bribe can lead to a loss of income. The indicator of interest was whether a participant offers (in the role of citizen) or accepts (in the role of bureaucrat) a bribe.

Due to the smaller sample size, it was not feasible to examine the effects of both positive and negative messaging, so I chose to focus on positive messaging, given the indications of positive messaging’s greater promise from the first study. Half of the participants, selected randomly, were shown the flyer with the positive message from Figure 2. After engaging in other parts of the study, they then participated in the bribery game described above.

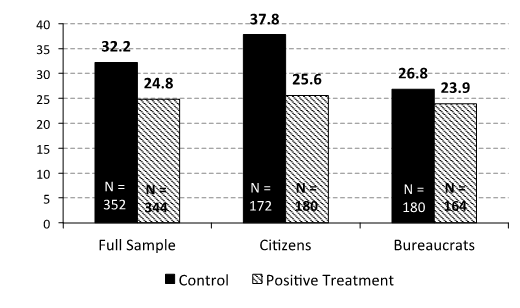

Figure 4 displays differences in bribe rates across participants shown the anti-corruption flyer and those in the control group. In the full sample, the rate of giving (in the role of citizen) or accepting (in the role of bureaucrat) a bribe was 7.2 percentage points lower among the group exposed to the flyer. This effect is apparent in both roles, but it is especially pronounced among those offered a chance to give a bribe (i.e., “citizens”)—a difference of 12.2 percentage points.

Figure 4: Results of Laboratory Experiment (Percent Giving/Accepting Bribe)

One might wonder if this result simply reflects the fact that participants shown the flyer were avoiding unethical social behavior in general, rather than reacting specifically to the anti-corruption message or the message that bribery is declining. However, exposure to the flyer had no effect on participants’ choices in other experimental games unrelated to corruption, including a game designed to measure dishonesty and cheating.

In summary, the laboratory experiment provides additional evidence that a positive message emphasizing how corruption among other citizens is declining can productively harness social norms to contribute to decreased willingness to participate in bribe transactions.

Policy Implications

Given government agencies’ and civil society activists’ reliance on anti-corruption messaging, the lack of rigorous research on informational campaigns’ effectiveness is concerning. This is particularly true considering the possibility for messaging to backfire, especially if a campaign contributes to impressions that corruption is widespread or increasing—an implicit cue that corruption is considered by many to be socially acceptable.

The evidence discussed above does suggest, however, that specific types of messaging may be effective. In particular, messages about corruption decreasing or being less widespread than citizens often believe may be able to employ the power of social norms in constructive ways.

These studies presented above are only a preliminary step. They did not, for example, examine whether the impact of anti-corruption messaging persists over time, nor did they explore the effects of real-world informational campaigns in which citizens encounter messages on a repeated basis and through various media. Whether the results can be replicated in other studies and in other countries also remains to be seen.

While the results are tantalizing, the biggest policy message is that informational campaigns should be carefully constructed and thoroughly researched. The potential of well-constructed messages may be high, but the inadvertent consequences of poorly constructed ones may be equally impactful.

Jordan Gans-Morse is Associate Professor at Northwestern University.

[1] Peiffer, C. (forthcoming). Message Received? Experimental Findings on How Messages about Corruption Shape Perceptions. British Journal of Political Science.